On The Bench: Where the Hell is that Buzz Coming From?

If your want your studio wiring to be hum- and buzz- free, you’ve got to plan ahead.

Text: Rob Squire

Studio wiring is one of those tasks that should be so straightforward and predictable that we could happily and confidently leave it till the last phase of a studio’s construction. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Wiring a studio takes planning and skill, yet it still remains one of the most neglected and misunderstood aspects of studio construction. Many new studio owners not only leave the wiring till last, they also fail to consider the costs involved, or appreciate the research, time and effort that cabling requires.

Right now I’m mapping out a wiring scheme for a client who has bought and refurbished a ‘vintage’ console, as well as added a multitrack tape machine and ProTools rig. The focus to date has been on all the big ticket items but now that all the fancy gear has been levered into the control room, the client seems somehow surprised that a random bunch of dirty old looms that came with the console won’t magically plug this new setup together.

ESTABLISHING THE GROUND RULES

Obviously, some setups are much more complex than others, but are there some common rules that will yield a reliable, clean and noise-free result for any setup, large or small? The answer is yes… and no.

I often see studio wiring as a combination of science and art. The technician in me cries out that it should be the preserve of science alone, however, hard won experience has shown me that sometimes the perfect solution for a clean wiring installation breaks all the rules and you have to yield to what works.

The key to a successful wiring installation is to start off on the right foot and from there on in, be consistent. It’s more a marathon than a sprint and time spent planning and getting the first steps in place will pay dividends down the track. Thus, the first step is actually nothing to do with the audio wiring, it’s all about your mains wiring. So leave the soldering iron turned off for the moment and instead go and find yourself a good electrician!

BUZZES & HUMS

I had a call this week from a studio owner who runs a well established facility, asking about getting the studio re-wired. “Why the sudden desire to rip it all out and start again?” I immediately asked. “The wiring has been in place for years.”

“Well, we’re getting all these intermittent hums and buzzes,” he said, “and it’s driving us and our clients nuts. Nothing seems to make sense.”

Following some very specific questions, a picture began to emerge. When asked: “So, when you plug a guitar amp into the wall in booth A, and you don’t have anything else connected – no DI linking, not even a guitar plugged in – does it buzz more than when it’s plugged into a socket in the kitchen?” The answer was, “Yes!”

My advice to them at this point was that they needed an electrician, not a technician. The studio in question is in an old inner city building, and the history of the original construction and studio wiring is lost in myth and legend. Older inner city buildings are likely candidates for low mains voltage, as are residential buildings at the end of a supply distribution run. If you notice incandescent lamps dimming at various times of the day and find a correlation with an increase in hums and buzzes, then it’s time to either have an electrician (or your power authority) come and monitor your mains power voltage over, say, a 24-hour period.

GOOD POWER

In a studio you need good power. Good power is about the consistency of the mains voltage supply, but unfortunately this can fluctuate wildly in the real world. Establishing that your studio is receiving 230Vac – or something pretty close – and that the voltage doesn’t wobble all over the place as the demand for power in your area goes up and down, is an excellent starting point.

The voltage range that authorities can legally supply may not be good enough for your studio, especially if you have tube equipment or large, hungry console power supplies. Inconsistent voltage causes all manner of dramas. I’ve struck tape machines that would throw up error messages and go nuts trying to transport tape smoothly because the mains voltage into the building was dropping to 210Vac, which is at the lower end of what is legally allowed to be supplied.

GROUND RULES

The earthing system of mains power outlets is also a very important aspect of a studio’s wiring. This is one of those jobs that is much easier to do when the electrician first installs the mains wiring and outlets or GPOs (General Purpose Outlets), than it is to come back and correct down the track. The electrical requirements of a studio are actually very simple, however, they’re unusual compared to run-of-the-mill domestic or industrial installations, so an electrician who can work with you on this one and understands your special requirements is essential.

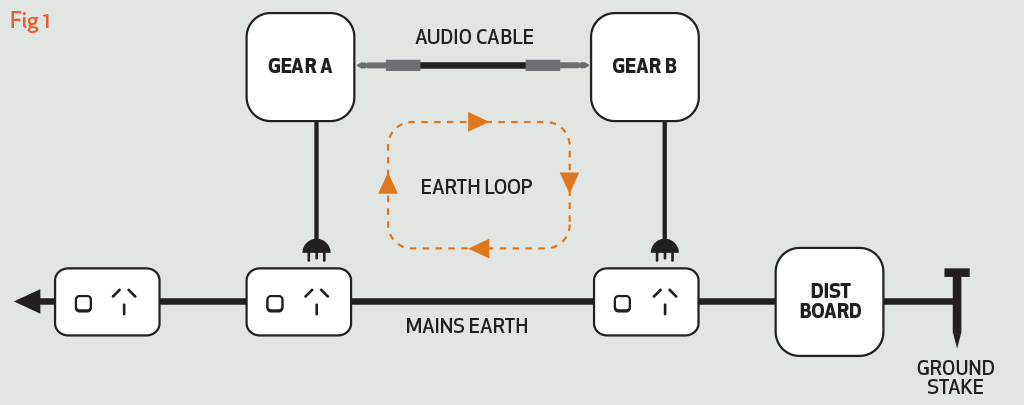

So what are these special requirements? Well, normal mains wiring simply loops the active, neutral and earth wires from one GPO to another. A single cable containing these three wires is used and GPOs are typically strung in a daisy chain, one after another, until the maximum for that feed from a single circuit breaker is reached. Unfortunately, for us audio types, this standard daisy-chaining approach has the potential to create an earth loop, whereby connecting various pieces of audio equipment together, fed from different mains GPOs and also interconnected to each other with audio cables, enables small leakage currents in the mains earth cables to flow through the audio earths. This superimposes hum and buzz on your audio signal – bad news indeed.

The solution is not to connect the earth wires from one GPO to another, but rather, for each individual GPO to have its own earth wire that travels directly back to the mains distribution board. Once there, it joins with all the other earth wires coming from each GPO, and it’s at this point that the connection to physical earth, i.e. the ground beneath our feet, is made. This is a good example of what is referred to as ‘star earthing’, where each individual point at which you can access a mains earth – namely a power point – is at the end of its own ‘arm’. That arm only connects then to all the other ‘arms’ at a single point.

Now before you rush out and wildly start ripping out GPOs with the view to star earthing them all, you need to understand that this is a job for a licensed electrician only. That earth exists to provide electrical safety, not to keep your studio hum free, and the importance of a correctly connected and low-resistance mains earth is paramount.

WHAT ABOUT THE OTHER EARTH?

In a studio environment there is, of course, that other earth that we’re all more familiar with, that is always a topic of discussion. This is the signal earth, the one connected to Pin 1 on an XLR, or the sleeve of a TRS plug. This signal earth is also the connection made to the shielding of a cable that carries audio signals. On this type of audio cable, the shield protects the internal signal wires from electrical interference, including the radiated 50Hz field from mains cabling and radio frequency (RF) signals of TV, radio and mobile phones etc.

All off-the-shelf cables connect this earth at both ends of the cable, i.e., an XLR male-to-female mic cable has Pin 1 of both XLRs connected to the shield of the cable. In fixed studio wiring, however, this isn’t always the most desirable scheme! From examining the earth loop created in Fig. 1 by the combination of signal earths and mains earths, we can see that one way to break this loop is to disconnect the signal earth wire at one end. It might come as a surprise to some, but this is common practice in many studios with installed audio wiring. Disconnecting the signal earth (which is also the cable shield) at one end (as shown in Fig.2), eradicates the link responsible for these dreaded hums and buzzes.

What is most important here is to be absolutely consistent in the choice of which end is connected and which end is disconnected, or left ‘floating’. The only cable that must have the earth connected at both ends is a mic cable, or any loom that may be used to connect microphones. The reason for this is that microphones are generally ‘floating’ devices already, and while the body of the microphone will connect to this signal earth, it normally doesn’t connect to any other earth. This prevents it from becoming a part of any loop and it will always be at the end of a star’s arm – i.e., only have one ground connection. While dynamic microphones will still work with the earth lifted from Pin 1, condenser microphones won’t work at all if the shield is disconnected, and as much as anything this is a good reason for always maintaining a microphone’s connection to Pin 1. Condenser microphones use this earth connection as a part of the powering circuit for delivering phantom power and disconnecting the earth simply means the mic will not receive any, and therefore not function.

This core requirement of microphones suggests the rule for determining which end of an audio cable should consistently be floated and which end connects to earth, Pin 1 or the sleeve. If we leave all the earths connected on any cable that connects to a device’s input and float the earths on all cable plugs that connect to a device’s output, then we ensure that the earthing will always be correct, including for microphones. To reiterate, the male XLR we’re wiring up to the input of a mic preamp has the earth connected, while the female XLR we’re wiring up to the preamp’s output has the earth floating (or lifted). Stage boxes and individual mic cables should always have the earth connected at both ends.

From looking again at Fig. 1 you can see that, regardless of the configuration of the mains earth wiring, lifting the signal earth or shield wire at one connector results in the earth loop being broken. The result? A hum-free connection. What you must ensure is that only one end is floated. If both ends are lifted then the protective shielding of the cable is lost.

When combined with fully balanced audio signals, the combination of star earthing of mains GPOs and floating one end of each audio cable interconnect will get you as close to a guaranteed hum- and buzz-free studio as possible.

What is important here is to be absolutely consistent in the choice of which end is connected and which end is disconnected, or left ‘floating’.

THEN THERE’S THE REAL WORLD

However, all these good plans often come unstuck in the real world, especially once unbalanced equipment is introduced and other quirks are found in equipment that just won’t play ball.

The general approach with unbalanced equipment is to treat it, as far as possible, as you would a piece of balanced equipment. To start with, always use balanced cable for interconnects, with the shield wire still connected at one end only. However, with an unbalanced connector, what would normally be the cold (or negative) wire will now need to connect to the sleeve (or ground) contact of the tip and sleeve or RCA plug.

In an ideal world, all manufacturers would stick to a universal standard when it came to connector wiring and the presentation of balanced and unbalanced signals. However, while the situation is certainly improving, you still come across occasional curve balls to test your patience from time to time. One of these – that is thankfully not all that common – is the presentation of unbalanced signals on XLRs wired with Pin 3 hot, rather than Pin 2. If presented to a fully balanced input, the worst that will happen here is that the phase of your signal will be inverted, but if this sort of output hits an unbalanced input, it will require a custom wiring job for any signal to emerge unscathed.

Another more common situation with unbalanced units is the use of 1/4-inch tip & sleeve sockets, where the ring position in the socket goes nowhere. A typical TRS (tip, ring & sleeve) plug is wired tip (hot), ring (cold) and sleeve (ground). With the ring connection missing in a mating socket, this results in the cold connection flapping in the breeze and the result can be unpredictable. You might lose some level (say 6dB) or, if the unit at the other end of this connection is transformer based, you’ll lose lots and lots of signal. In fact, a very low-level and thin-sounding signal has all the hallmarks of faulty interconnection of transformer-based equipment where one connection – either the hot, or more usually, the cold – has not been made.

Many older outboard effects units often had simple tip & sleeve sockets with unbalanced signal inputs and outputs, and from looking at the socket from the outside you won’t know if the ring connection is absent. These are the ones that will require some research or experimentation to discover if you need to wire a TRS plug as a simple tip and sleeve, with the cold (or negative) wire connected to the sleeve.

And the art in all of this? Neatness. Keep your wiring neat and tidy. It helps when you come back a couple of years later to add a new piece of equipment or even when showing a potential client around the studio: they’ll think; “Well at least the wiring looks good!”

RESPONSES