Mixing Synth Pop: Vocals

In the forth and final part of this series about mixing Synth Pop, mixer/engineer Tristan Hoogland describes his processes for mixing lead and backing vocals.

Tutorial: Tristan Hoogland

Vocals are the most crucial thing to nail in any mix. We want our lead vocal to be upfront and present, yet have its own space to exist and still be connected to the rest of the track. To add further challenges sometimes vocals are recorded in a well-treated room through a great signal chain, and sometimes they’re recorded in a bedroom with no pop filter. It’s important not to get hung up on how poorly something is recorded – take it on face value, evaluate what you need to do, and get to work.

HELLO? HOUSEKEEPING!

If there’s a plugin everyone should have in their vocal toolkit it’s iZotope’s RX. It solves problems in ways that EQ and manual editing can’t. Modules I use frequently include Mouth Declick and Deplosive.

Mouth Declick removes distracting mouth noises like lip smacks. The default setting of 4.0 works well in 90% of cases, but I may increase it higher or double process it for more stubborn clicks.

Deplosive aims to remove plosives. While it’s effective, there can be a trade off in the body of the vocal if used inadequately. Settings vary, but I start with the frequency set to 150Hz, sensitivity to 5.0, strength to 6.0, and adjust to taste.

For both modules I duplicate the main playlist, process the entire audio in AudioSuite and fly up the processed region as a click appears. Avoid batch processing as it can affect diction (although I’m less cautious about that with doubles and BVs, as discussed later).

VOCAL PROCESSING CHAIN

My vocal processing chain is almost always the same:

- De-Esser #1

- De-Esser #2

- Corrective EQ

- Flavour/Additive EQ

- Compressor/Limiter #1

- EQ

- Smoothing Compressor #2

- Tone

- EQ

Sometimes I’ll use all of this, sometimes I’ll use none. I start with everything in bypass and, while the order rarely changes, I will engage whatever I feel needs attention first. For example, I may engage Compressor/Limiter #1 while getting a balance going, then some EQ, maybe some de-essing, then back to Compressor/Limiter #1, etc.

SSSIBILANCE

The best place for a de-esser is at the top of the chain. This allows us to control sibilant events and dial in top end afterwards without the vocal sounding harsh. I use two in split-band mode, each focusing on different areas of the vocal; the first targets higher sounds like ‘T’ and ‘S’, the second targets lower sounds like ‘Ch’, ‘Ka’ and ‘Sh’.

For male vocals I’ll typically set De-Esser #1 somewhere between 6kHz and 20kHz, and De-Esser #2 to somewhere between 2kHz and 5kHz.

For female vocals I’ll typically set De-Esser #1 to somewhere between 6kHz and 20kHz (same as male vocals), and De-Esser #2 to somewhere between 3kHz and 6kHz.

Ideally we want these working independent of each other, so that each is catching things the other isn’t. It’s not uncommon to see anywhere between 5dB to 10dB of gain reduction going on in each instance, but use your ears and aim to have them tonally sitting in alignment with the rest of the vocal passage.

CORRECTIVE EQ

The trick to having a vocal sound clear and present is less about cranking high end, and more about better management of low end and mid frequencies. With the vocal up, evaluate what state it’s in and what areas need attention first. I find it to be typically one of three things:

Murkiness/boxiness (150Hz to 400Hz)

Honkiness (500Hz to 1.5kHz)

Harshness (2kHz to 5kHz)

A good rule of thumb is “the lower the frequency the broader the Q, and the higher the frequency the narrower the Q.”

I’ll apply a high-pass filter to remove any rumble and other excessive non-musical energy. I’ll do this by sweeping it up to around 400Hz, and then bringing it back down until the integrity of the vocal is regained. This could be as low as 80Hz or as high as 300Hz.

Low mids are the most delicate area to get right. Too little and things sound anemic, too much and they sound dull and unclear. Attenuating 200Hz to 400Hz with a moderate Q (around 1.0 to 3.0) reduces cloudiness and improves intelligibility, particularly if the singing is in a lower octave. Conversely, if there’s a lot of belting you’ll want to retain more of the low mids. Further up there can be some boxiness and honkiness that’s worth reining in; 500Hz to 1.5kHz can be a honky area that I’ll usually attenuate with a medium-tight Q. I’m always careful around this area, however, as I find it is where the character of most vocals are found.

High register sung vocals generally have a lot of energy in the upper mids, which can be fatiguing if not managed well. I rarely do broad cuts here, preferring tighter attenuation of harsh resonances. It’s not uncommon to find one or two hot frequencies that spike between 2kHz and 5kHz, and I’ll use FabFilter’s Pro-Q3 with a moderate to tight Q (3.0 to 10) and pull it down, anywhere from 4dB to 15dB depending on how bad the offending frequency is.

EQ, BUT MAKE IT DYNAMIC!

A useful feature available in many EQs is the Dynamic feature. This operates somewhat similarly to a multiband compressor, but it works particularly well on vocals as we have finer control over the Q compared to a multiband. I resort to a Dynamic EQ when the resonance of a vocal occurs infrequently, or when the vocal moves up and down through the register frequently.

Instead of continuously removing the frequency with a standard EQ, I’ll engage the dynamic function and bring down the threshold until I achieve uniformity. Ideally we want it to attenuate the target frequency only during heavy moments that bring out the resonance, and to relax at other times.

TO BOOST OR NOT TO BOOST?

While I prefer reductive EQ, it’s sometimes beneficial to have an additive approach. When boosting I’m looking to enhance areas that feel under-represented, typically lifting the top end to improve intelligibility. Furthermore, applying de-essing can result in a duller tone that we may want to compensate for. For this job I’ll reach for character equalizers like an SSL or Pultec. The SSL is a sharp and focused equalizer, whereas the Pultec is smoother and lighter.

On the SSL I’ll usually open up the vocal by adding some air around 8kHz to 14kHz, which helps it sit a little more up top of the mix. With the upper mid band, I’ll find a spot between 3kHz and 7kHz that excites the transients of the vocal, honing in on nicer qualities of those S’s and Ch’s; basically, anything that brings the voice forward. On the Pultec-style EQ I’ll often reach for something like 10kHz or 12kHz with a wide bandwidth and open it up. I’m more conservative when boosting, rarely pushing more than a few dB as I rely on reductive EQ to do the heavy lifting.

COMPRESS TO IMPRESS

When compressing it’s always best to focus on tone, not dynamic control. I typically like to use two compressors in series for vocals; the first is something fast that’s quick to grab the front of the vocal, the second is something slower that smooths out the overall performance.

The first compressor in my vocal processing chain is an 1176, which I have set up with the attack at 3, release at 7 and a ratio of 4:1. What I’m looking for here is to clamp down on the heavy moments in a vocal, particularly the loudest passages. This will, in turn, alleviate the amount of work the second compressor needs to do. I’ll increase the input until I start to hear the vocal thicken up. Depending on how dynamic the vocal is, the gain reduction meter could be working anywhere from 7dB to 20dB during the loudest passages! Having it operate between 3dB to 7dB most of the time isn’t unusual. The 1176 has a lot of mid range character and so I may pull out some mids afterwards.

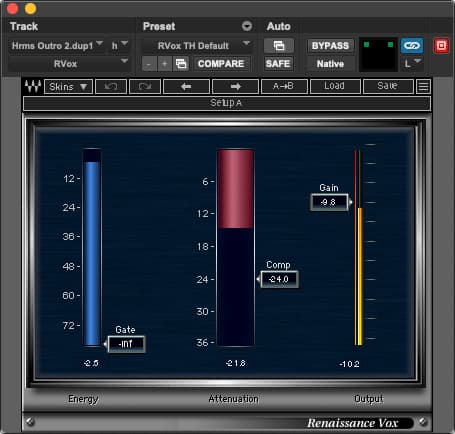

The second compressor I reach for is RVox, but sometimes it can be an LA2A or TubeTech CL1B. RVox is a great vocal finalizer that, to my ears, compresses and limits the signal nicely. How hard I work RVox varies greatly depending on the state of the vocal; sometimes knocking back just a few dB is more than enough and sometimes slamming it 20dB works wonders. It often requires a bit of back and forth with the 1176 to get that relationship working.

WHY EQ BEFORE COMPRESSING?

It’s mostly about tuning the EQ to the compressor. The reason we EQ before compression is because we want to feed our compressor a signal that won’t be continually forced into gain reduction based on non-musical or undesirable excessive energy in a particular frequency range (e.g. usually too much low end). The other part of the equation is that after some time you learn what a compressor wants to see going into it. I like to think of this as tailoring the signal to the compressor so it can do its job more efficiently. That’s why it’s important to do these steps in conjunction with one another, and to go back and forth as you introduce a new processor down the line. You get a sense of what each device wants to see.

TONE/DRIVE

Tasteful compression usually brings all the drive and saturation I like in a vocal, but there are times where recordings come in that, even after processing, feel completely lacklustre. My favourite tool for this is Soundtoys Radiator. I set this up at the end of the chain (post compression) where I have a steady signal to feed it, because having it respond to a dynamic signal makes it harder to park. I’ll either drive it hard and mix in a small amount, or be more conservative and have the mix at 100%. In both cases I’m referring to a mild injection of tone rather than full over-the-cliff annihilation, but that can also be achieved.

SPLIT IT!

I like to split the vocal across two tracks, one for the verse and one for the chorus. This offers flexibility; EQ and compression settings can be better tailored to suit the vocal range and intensity of each part respectively.

EFFECTS

Producers typically provide you with effects of their own and in most cases I’ll make those work, but I may expand upon what’s already there or recreate where appropriate. Each song is prescribed a unique dosage of effects and it’s important to know what the producer has in mind when including them. I like to use a combination of effects and always have the following ready at my disposal:

Pitch-Shifting/Chorus: Microshift, Dimension D

Reverbs: Small Room, EMT Plate #1, EMT Plate #2, Spring, Long Hall

Delays: Slapback, Medium Delay, Long Delay

PITCH-SHIFTING/CHORUSING

Pitch-shifting can really help in achieving apparent width and size. My favourite tool for this is Soundtoys Microshift. My default is setting II with the focus knob at 160Hz and I’ll typically have the send set anywhere between -10dB and -20dB depending on how much I’d like. Exaggerating the Detune and Delay knobs can help in achieving even more ambiguity and width.

ROOM

Adding a room reverb is a nice way to add a bit of diffusion to the vocal. I like using it if the lead is sounding too stark. I don’t use room reverb’s too often when mixing pop, perhaps 30% of mixes where the arrangement is sparse. I generally prefer it to be very short and unnoticeable; my favourite plugin for this is the Medium Room setting in ValhallaRoom. It tends to be quite spitty and bright so I’ll usually bring the hi cut way down with a shortened decay (60ms to 90ms).

EMT 140 PLATES

Plate reverbs are complimentary to vocals due to their clear and rich character. I like UAD’s EMT 140 and I’ll toggle between plate A and B depending on the colour I’m going for (A is brighter, B is more neutral). I’ll set the decay to taste, but two seconds is a decent starting point. I enjoy introducing a moderate pre-delay of around 30ms to 80ms depending on the song, but extending the pre-delay to longer extremes like 200ms can be fun. Ultimately I tune this by the feeling, and by the phrasing of the vocal.

LONG HALL

My favourite hall for this is the Concert Hall algorithm in Valhalla VintageVerb. It has a very nice, hazy furriness to it that works well at creating a large backdrop without drawing too much attention to itself. The default setting is surprisingly effective in most scenarios, though I may extend the decay time if the song calls for it or I am doing a large throw. It is heavy on the low end so I’ll usually roll off a lot both before and after the effect so it doesn’t take up as much headroom. I like to try to get this to work as an extension of the plate.

SLAPBACK

I like UAD’s RE-201 for this duty. It’s got a thin ‘mid-rangey’ sound to it and distorts on the front end nicely. I use it in multi-mono mode starting with both channels linked to set the rough delay amount I’m after – anywhere between 80ms to 130ms depending on the song. I’ll unlink the channels and offset each side slightly (e.g. 10ms to 15ms up and down respectively). Driving the input fuzzes up the delay nicely and also helps get a more consistent, compressed like level coming out.

MEDIUM & LONG DELAYS

Delay’s are generally more effective than reverb in dense pop arrangements as they take up less room in a mix. I have two delay channels set up in my arsenal, a medium and a long delay.

I like using Soundtoys EchoBoy. My usual aim for the medium delay is to feel like a tucked in reverb – if I can hear the repeats clearly, it’s too loud. First, find a subdivision that works well for the feeling you’re going for. Sometimes this ends up being 1/4th or 1/8th, but it surprises me how often I’ll end up with something slightly off beat. I’ll set the feedback to anywhere between 10 and 2 o’clock depending how deep I want it to feel. I’ll adjust the hi and low cuts, focusing on aspects of the vocal that every so often make the delay jump out. I’ll also remove quite a lot of low end, focusing on the dry vocal while making this adjustment and find the spot where the dry is clearly dominating the low mid frequencies without clutter.

I’ll reserve the long delay for throws, which conversely to the medium delay are to be noticeable. We can do this off a send, but I duplicate the lead vocal track and its processing and throw the delay on as the last insert. This allows me to control, with great precision, the words I’m wanting to throw off as I can trim the region, fade in or out, etc.

PRE- & POST-EFFECT PROCESSING

Implementing EQ before and after your discrete effects returns pays dividends. This offers the flexibility to change the character of the effects by altering the sound going into them and also processing the sound coming out of them. I’d also encourage experimentation around compression and distortion, both pre- and post-effects. For example, compressing the effects return can almost act like a sidechain from the dry signal, pulling back the effect to allow the dry signal to creep through and return in the gaps between phrases.

BACKING VOCALS

There are numerous types of backing vocals that may exist in an arrangement, but for the purpose of this segment we’ll focus on the most common variant: harmonies.

Where possible I prefer to work with groups rather than individual harmony parts, primarily because the balance of the group is what the artist and producer are used to and it’s easier to work from a place of agreement. If more freedom is needed further down the track, then we can resort to the individual layers.

I’ll approach things like de-essing, mouth declicking and so on similarly to how I described earlier for lead vocals. Unlike lead vocals, however, my treatment on harmonies is quite broad and aggressive because I aim for them to surround the lead vocal when they appear. I like rich sounding harmonies and this often means attenuating low mids and mids, along with some heavy compression, all in the interest of keeping the BVs clear of the body and focus of the lead vocal.

As can be seen in the example, that is exactly what I’ve done to this stack of harmonies: a high pass filter at 220Hz, a broad 9dB cut around 250Hz and another cut around 900Hz. I also added some air around 14kHz on the SSL. Following the EQ is the TLA-100, which is just doing a little bit of musical compression (around 3dB max) followed by RVox, which is doing most of the heavy lifting – slammed quite aggressively (averaging 12dB to 15dB of GR) to bring out those upper harmonics and keep them solid. It’s important to note that these vocals were recorded very well and adjustments were made based on how they related to the lead.

In regards to effects I’ll first consider what’s on the lead. If the lead has a significant amount of ambience I may keep the BVs mostly dry, which in context is hard to detect if there’s a lot of reverb already present. More commonly I will send them to UAD Dimension/Studio D to add a bit of density and richness. If I feel like they need some reverb I’ll usually send them to a plate – typically Valhalla’s Plate, which I like because it’s quite ‘vanilla’ and thin sounding.

RESPONSES