What’s In The Lunch Box?

500 Series Compressor Shootout.

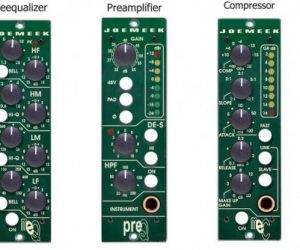

In the last five years the 500 series rack format has seen an enormous surge in popularity. Originally an analogue console ‘penthouse’ format invented by API to house its mic pres, EQs and compressors above the faders and pan pots, the 500 series went portable with the introduction of that company’s iconic ‘Lunchbox’. From being the domain of the API and/or DIY enthusiasts the format gradually attracted other boutique outboard manufacturers with its ready-made power supply solution and small footprint. Today there is nary a sonic task that hasn’t been addressed by some ingenious 500 series designer. From A/D converters to phase alignment tools and ring modulators, there’s something for everyone, and the challenge for the designer is always the same: how to pack the most useful features and the highest sonic performance into this smallest of module formats.

What follows is by no means a comprehensive survey of the 500 series compressors out there in the audio marketplace. Rather it is a small sample of the ever-growing variety of flavours available, and I hope it will give AT readers food for thought when they contemplate embarking on a dalliance with the format or adding to their 500 series module collection. In future we’ll also cast our eyes and ears across some tasty EQ options but we’re kicking off this series of articles with a look at the wonderful world of 500 series dynamics control. All modules were tested in an ageing Old School Audio rack as well as a brand spanking new Radial Workhorse. To curtail any raised eyebrows it’s worth noting that de-essers compress high frequencies and that’s why there’s one in this dynamics shootout. I’ve tested each module on a wide variety of sources and applications and done a lot of listening. Of course these assessments are based on one person’s subjective experiences with each unit – my trash may be another man’s treasure so bear that in mind as you read this. Must be lunchtime!

CHANDLER LITTLE DEVIL COMPRESSOR

The Little Devil Compressor is a feature rich unit that offers two distinct compression types as well as a 5-position side-chain filter, input and output gain, continuously variable attack and dry/wet mix controls. The two compression types are the harder Germanium curve and the more forgiving Zener curve. Both offer high, medium, and low compression ratios and a choice of fast, medium or slow release times. There is also a hard bypass toggle switch at the bottom of the unit and a tasteful kidney-shaped backlit VU meter that graces the top of the fire engine red faceplate, showing gain reduction only. It’s a good-looking module and offers some real hands-on dynamics control.

The Germanium curve is pretty dark and coloured and reacts to transients much more quickly than the more airy and gentle Zener setting. I first tried a pair of Little Devils on drum and mix bus duties and quickly found that only the Zener curve really held up in this application as the Germanium tended to shut down tone-wise pretty quickly even at low input settings, and neither flavour really stood out as a winner here. Moving on to individual track compression I had a lot more success with the Zener setting on guitar, bass and snare, particularly when re-introducing some dry signal into the chain at higher compression ratio settings with a shorter release time. Another favourite setting was the darker Germanium curve on slightly hard and/or strident male vocals and overly bright guitars where its combination of smoother tone and mid-range power did very nice things tonally, as well as effortlessly controlling the dynamic range. The mix feature is one of the unit’s strong points, as is the variable side-chain filter which allows low frequency information to slide in under the compressor’s nose without setting off unwanted pumping artefacts. The choice of frequencies between 30Hz and 300Hz here allows for some subtle control of how much these lower frequencies react with the compressor’s knee.

Overall I found this comp did its best work at moderate settings (-2dB to -5dB) and indeed it was quite hard to get the Little Devil to misbehave in any useful way so I reluctantly came to the conclusion it was less of a ‘colour’ or ‘effect’ compressor than I had expected. The Little Devil is also a comp that delivers its best results after a fair bit of play and, while it wouldn’t be my first choice in a lot of applications, when it does work it works very well indeed, especially on electric guitars and dynamic male vocals.

At the higher ratios and thresholds the LA500 can really smash and grab in a musically pleasing way

RADIAL ENGINEERING KOMIT

Radial Engineering has come up with something a little different here. The khaki and white coloured Komit offers continuously variable compression ratios from 1:1 to 10:1 and a separate stepped limiter circuit. In between these is a continuously variable gain make-up stage that can also be used to drive the limiter harder. The limiter has a few tricks up its sleeve with a bypass step, and another labelled ‘BW’ that doubles the compression ratio and acts as a bullet-proof brick wall limiter at the compressors maximum setting (effectively 20:1) [the shot obscures both limiter steps, you’ll have to squint hard or believe us on those – Ed]. The limiter’s threshold offers 10 settings in 3dB steps and utilises an old-school diode bridge circuit that can be driven into quite heavy distortion at higher thresholds. The compressor offers switchable slow, medium and fast speeds and utilises a feed-forward auto-detection topology that makes the compressor less tweakable (only two controls) but also more forgiving to operate. Input level can be switched between +4dB and –10dB operating levels and there’s also a link switch for stereo operation and a snazzy 10-bar LED meter at the top of the unit to monitor output and gain reduction levels simultaneously.

The Komit seemed to require more input gain (even at the higher input level) than all the other units reviewed here before I could get the compression to work on my signals. However, once I did get it properly working The komit offered up a nice thickening effect at robust settings, lending weight to kick and snare drum sounds while breaking up easily once the gain and limiter thresholds were pushed. On vocals the Komit was good on mild settings at controlling excessive dynamics while leaving the original tone of the voice well alone. On guitars and bass the Komit seemed to thrive on lower frequency information and again I found the Komit very willing to start breaking up and emphasising compression artefacts. While the distortion characteristics can deliver a pretty bombastic rendition of an electric guitar or drumkit, at times the sound can get a little honky in the lower midrange. The brickwall limiter is a very handy tool when used carefully and can control overly dynamic information quite well, although the different gain structures required by this unit made it hard to tell exactly how much limiting was being applied. The Komit wouldn’t be my first choice for vocals outside of moderate settings, but showed itself to be a very handy kick, snare and bass comp, with its knack for handling low frequency content.

EMPIRICAL LABS DERRESSER

The DerrEsser is a bit of a surprise package and those who assume, as I did, that the DerrEsser is simply a 500 series de-esser with a funny name are quite mistaken. Subtitled a ‘High Frequency Fixer’ in the manual, the stylish black, silver and blue DerrEsser is equipped with continuously variable threshold and high frequency controls and in its most basic ‘all buttons out’ mode is a capable de-esser. When High Frequency Limit (the first of three white buttons) is activated it becomes a dedicated soft-knee compressor for the high frequency content of your signal above the selected frequency. When the ‘Listen’ button is engaged you hear only the portion of the signal acted upon by the de-esser or HF Limiter and in the latter case what you also then have is a handy high pass filter with a sweepable cut-off point down to 1kHz. When the Listen button is activated alongside the final Low Pass button this situation is reversed and you have yourself an even more handy low pass filter. The unit squeezes in a 7-segment LED gain reduction meter up its left side, a hard bypass switch, and a clip LED that lets you know when it’s gone ‘BAD!’

In use the DerrEsser is pretty straightforward and I had it up and doing various audio tasks in no time. First and foremost it is a very good de-esser. As with any de-essing processor you have to fiddle a bit with thresholds and frequency settings to get it to work smoothly (somewhere before lisping and other artefacts become apparent), but the results are generally excellent. Indeed you only realise how much it is doing when you hit bypass and hear the unprocessed signal! It is certainly at least a match for any of the other hardware de-essers I have used over the years and noticeably better than the usual software candidates.

I was even more impressed by the High Frequency Limit mode, particularly on vocals. Most of you will be acquainted with the sound of a vocal recorded via a slightly zingy condenser microphone straight to digital.

Treating one of these somewhat harsh signals with the derresser’s hf limit mode can be a truly transformative experience as the harsh qualities in the transients and the brittle high frequency tonality are gently tamed and allow the midrange to breathe more naturally.On spiky acoustic guitar the HF processing does a similar trick although the dynamic nature of the filtering can be exposed by more complex rhythmic information, so care must be taken here. Finally the high and low pass filter modes are nothing to sneeze at as they both sound great and the low pass filter in particular is useful in removing high end hash while preserving the integrity of a sound’s midrange content.

The DerrEsser is quite cheap by 500 series standards and yet in many cases it could prove to be more useful than many an esoteric EQ or compressor. The sonic equivalent of a cut and a style for your top end with a few tricks up its sleeve, the DerrEsser gets my award for innovative 500 series design.

JLM AUDIO LA500

Joe Malone’s offering in this shootout is the LA500, a 500 series version of the 2-channel 1RU Mac that the company also sells. The LA500 gives a vigorous nod to the Teletronix LA2A and LA3A devices of yore while adding extras such as a side-chain circuit and a choice of ratios. Like the units that inspired it, this is an opto compressor that varies its attack and release automatically, depending on the compression amount and ratio. This module is a very solid and stylish blackface affair with a circular backlit VU and two large chickenhead knobs for threshold and makeup gain. Above these are a trio of diminutive 3-position switches that control side-chain filter frequencies and bypass, meter output and gain reduction options as well as hard bypass for all processing. There is a choice of three levelling ratios (3:1, 5:1 and 10:1) and for those with basic soldering and instruction-following skills the LA500 can be ordered in kit form making it a very affordable dynamics option indeed for the DIY fraternity.

I threw the LA500 in the deep end on a vocal recording of Melbourne singer-songwriter Charles Hertzog. Charles has an amazing voice that, in the one song, can go from whisper quiet to literally making the whole room vibrate – I’ve never seen a singer who tests the limits of gear like Charles does. Thankfully the combination of an old Neumann U87 and the LA500 worked beautifully. On the 3:1 ratio the compression levels were occasionally running very hot but this comp never became pinched or tonally compromised and I was very happy with the results. Switching to rock drum bus duties I was also very impressed by the unit’s ability to saturate and add sonic weight. At the higher ratios and thresholds the LA500 can really smash and grab in a musically pleasing way, reminding me of one of my favourite ‘effect’ compressors, the API 525, in this role. Unlike that unit however, the LA500’s bonus in these kinds of more aggressive applications is that engaging the side-chain HPF stops the bass frequencies from dominating the compressor’s reactions, giving a beautifully magnified, harmonically rich picture of the kit where the kick drum image stays solid right through to extreme settings.

I really did find it hard to fault the LA500 other than occasionally wishing it had attack and release options, but then the charm of this unit is that it sounds great and doesn’t require too much in the way of tinkering. Any comp that sounds musical, can smooth out vocals transparently and also give the drum bus a good shellacking is a winner in my books. A super-competitive offering from a great Aussie company and one I’m pleased to say sits right at the top of the pile in this shootout.

The 527 definitely does that classic API thing – the hallmarks of fast transient response and tight bottom end

API 527

Last but not least is the most recent offering from 500 series granddaddies API – the 527 compressor/limiter.

The 527 packs a lot of features and borrows some ideas from the very successful 2500 stereo comp design while incorporating 2510 and 2520 discrete op amps and a transformer balanced output. Compression ratio is continuously variable and comes in several flavours with micro-switches for hard/soft knee, new/old (feed forward/feed back) circuit topologies and ‘Thrust’ enable. The Thrust circuit applies a high-pass filter before the RMS detector and is designed to preserve bottom end clarity. There are also switches to select gain reduction or output level metering (via the 10-segment LED meter), hard bypass and stereo link to another 257. Attack and release adjustment is via a single dual-concentric pot and there are also separate controls for threshold and gain make-up.

Right off the bat its clear that for all its bells and whistles, the 527 definitely does that classic API ‘thing’ – the hallmarks of fast transient response and tight bottom end keep this unit true to the sonic blueprint of the older API modules, while the options of old and new topologies, hard and soft knee compression curves and the Thrust control allow for extra flexibility and fine tuning when dialling up a sound. My first test of the 527 was as a drum bus sweetener and while I couldn’t quite achieve the rich gluey tonalities of my vintage 525 module, The 527 proved itself up to the task and generated a wide range of useable options from gentle tightening down to bombastic slamming. I settled on a combination of soft knee, new topology, very fast attack, medium release and high ratio for a nice heavy compression effect and engaging the thrust switch seemed to drive the unit harder, generating even more pleasing harmonic distortion and a subtle brightening of the top end. Most noticeably, the 527 doesn’t blow out and get messy on bass heavy sources even at super aggressive settings, and this sets it apart from most of the other comps in this shootout. The 527 also does a great job on snares and kick drums where the differences between old and new topologies are quite evident. The ‘new’ setting is more moderate and allows relatively transparent control of transients and sustain, while the ‘old’ setting generates more thump and wallop and seems to exaggerate the lower midrange on medium attack settings. Switching from soft to hard knee, the compressor behaves in a more aggressive way and API describes this setting as more of a limiter-like effect. On acoustic guitars the 527 shines as a sweetener too, lending weight and drive to a strummed part, and making it easy to dial in emphases on the transients or on the tone of the guitar’s sustain. Finally on vocals the ‘old’ topology with a soft knee does a good job of reigning in vocals with 3-5dB of gain reduction, though here I think the API’s sonic footprint is better suited to rock vocals than softer folk voices.

Overall. the 527 impressed me with its tweakability and the range of applications it covers. For rock ‘n’ roll sonics the API gets a big tick in the box and it also wins the award for most controls per square inch of faceplate while not feeling particularly fiddly to operate.

RESPONSES