Wise Up: Elvis Gets Back With The Roots

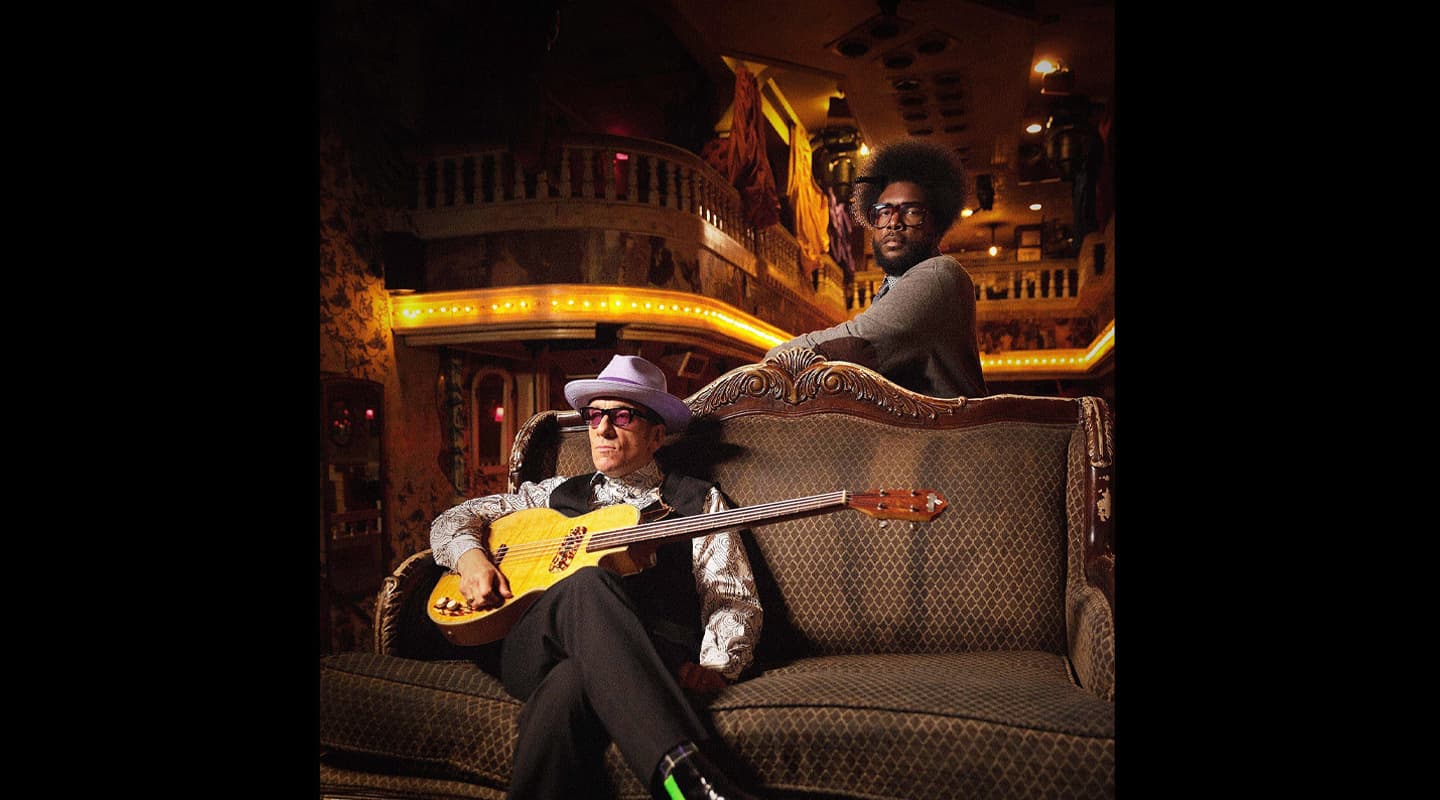

Steven Mandel managed to make a practise room at 30 Rock sound like a million dollar studio. It just so happened to house Elvis Costello, ?uestlove and The Roots at the time.

Wise Up Ghosts & Other Songs

30 Rock Photos: Steve Weinik

These are dark days for lovers of hi-fi audio; over-compressed and over-bright productions are only on the increase. But occasionally, through the pumped-up digital grey, you get an album that caresses the ears, rather than assaults them. Two recent pop albums up for consideration are Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories and Elvis Costello & The Roots’ Wise Up Ghost and Other Songs. Random Access Memories became instantly celebrated for its audiophile approach; helped by a million US dollar recording budget and pre-release mini-movies describing the lengths the French duo went to ensure the album wore analogue 1970s aesthetics on its sleeve. It was an open invitation to return to the expensive, laborious, big studio approach of the pre-digital Golden Age of record production. Topped off with resurrected disco-era icons. Wise Up Ghost and Other Songs, meanwhile, sounds almost as good, with a non-fatiguing natural spaciousness to the sound and arrangements; a gentle, silken high end; a huge yet tight low end; and impressive dynamic range.

Its admirable sonic qualities hint at similar working methods and budgets to the Daft Punk epic. It turns out, however, that nothing could be further from the truth. The man in the know is Wise Up Ghost’s engineer and mixer, Steven Mandel, who proudly proclaims that he “grew up as an analogue person who loved tape”. Despite his love affair, he explains, Wise Up Ghost was “made without a budget, before a record deal was in place, in a rehearsal room, and entirely in the box, in ProTools at 24-bit/48k. It’s not something I’m trying to promote, but I guess the record does have a warm sound, and a sense of expansiveness.”

As Mandel relates the full story of the album’s gestation, it gradually becomes clear that circumstances conspired to create something unusual, including the fact that it was made without a budget, and bizarrely, recorded and mixed for the most part in a tiny dressing room-cum-rehearsal space. It could nonetheless have turned out a mess, and this is the story of how, and why, it didn’t.

CROSSOVER PATHS

When news broke of the Wise Up Ghost collaboration there was widespread concern that Costello, a British singer-songwriter emerging from the 1970s New Wave movement, was jumping on the latest bandwagon, and that the world was going to witness a Costello-gone-hip hop car crash. In this day and age of extensive genre crossovers, the eyebrow-raising is surprising. Especially given Costello’s long reputation for eclectic collaborations, including with classical music acts like The Brodsky Quartet, all the way to Burt Bacharach, and Paul McCartney. And this could be one of his best. Costello’s intense, hoarse vocals fit seamlessly with The Root’s relaxed but deep muscular grooves. If anything, both Costello and The Roots sound revitalised, demonstrating a connection that usually takes decades to foster. Though, in truth, it did take a couple of years.

The collaboration originated when the two parties met at Late Night With Jimmy Fallon. The Roots, led by drummer Ahmir ‘?uestlove’ Thompson, have been the Jimmy Fallon show house band since the beginning of 2009, and later that year backed Costello on a version of the song High Fidelity, chosen by Mandel. Another year went by, and Costello was back on the show to promote his album National Ransom, playing an album track with the Roots and guitarist John McLaughlin. The stirring combination of wordy song and ballsy funk grooves was an indication of things to come.

And it just kept happening. Next up, Mandel recorded Costello and The Roots playing the Squeeze song Someone Else’s Heart, for a Squeeze tribute album. Everyone was vibed on the result, and the idea first emerged of Costello and The Roots doing an album together. Costello visited the Fallon show yet again in February 2012 to play some Springsteen songs, with The Roots backing him once more. By then, the collaboration was merely a matter of timing. The first steps involved a typical 21st century long-distance approach, with Costello cooking up ideas at his home studio in Vancouver, called Hookery-Crookery West, and uploading them so ?uestlove and Mandel could create their own takes in New York and fling them back Costello’s way. Once the songs were fleshed out, a batch of recording sessions followed in New York, Vancouver, and Philadelphia.

“It was an untraditional way of making a record,” remarks Mandel. “Because there was no record deal, there also was no deadline. So we were doing this at our leisure, when we were inspired. We would send things to and fro, and then haphazardly recorded the album in three cities. Three songs ended up being recorded live in the studio: The Puppet Has Cut His Strings, If I Could Believe, and Sugar Won’t Work, mainly with Ahmir, Elvis, bassist Pino Palladino and keyboardist Ray Angry, but the other songs were mostly recorded one musician at a time.

“In general, we were building things up piece by piece and working with a cut and paste montage-type approach to producing. It was somewhat new for Elvis, but for Ahmir and I, it’s second nature. Maybe we were trying to prove a point by throwing paint on a wall and then removing things. Elvis called it collage. You have these splatters of paint on the canvas, and pick and choose which you find the most interesting in a long process of arranging and editing, muting and un-muting, and decision-making. Even friends of mine who know a lot about how records are made don’t realise how the people that make them listen to it. The lead single Walk Us Uptown is 202 seconds long, and we carefully considered what happens in each and every moment. I mean, 202 seconds is a short time, but when you are creating something, it’s much longer.

“We were shooting for the space, air and feel of the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album from 1970. We intended to make the songs very sparse, with just drums, bass, piano, guitar and vocals. A lot of the greatest stuff happens in the silence. Having said that, we ultimately ended up filling more space than we intended, because it’s a constant battle to try to keep things sparse, and yet do the songs justice. If we felt a song needed horns, we’d add them, but tried to keep them as sparse as possible.”

Wise Up Ghost was made without a budget, before a record deal was in place, in a rehearsal room, and entirely in the box, in Pro Tools at 24-bit/48k

NO LOSS FOR WORDS

Mandel not only engineered the album, but also co-produced and co-wrote it, with Costello, and ?uestlove. And in manning the DAW, Mandel played a crucial role in the creation of the album’s apparent analogue aesthetic. Mandel’s own analogue roots can be credited to the 1970s and ’80s music he listened to as a kid — with a particular interest in Elvis Costello — and to his time as an intern at Electric Lady Studios in New York, where he began working in 1996. Fate met him quickly, because in 1998, when Mandel had graduated to assistant engineer, neo-soul singer D’Angelo came to record his second album Voodoo at Electric Lady. ?uestlove was one of the producers, Mandel and he hit it off, and not long after the D’Angelo sessions Mandel found himself in Philadelphia as The Roots’ main engineer. He has since worked almost exclusively with The Roots, and also engineers and mixes many of ?uestlove’s productions.

He’s led a charmed life, but this particular collaboration was perhaps Mandel’s most fateful coincidence. Unlike many of his studio colleagues, Mandel wasn’t a closet musician, but instead, he recalls: “The thing that got me into music and then engineering was lyric writing. I’m not a drummer or a guitar player, but a lyricist, and Elvis was a big influence on my lyric writing. From there I started looking into how to record. So in the first part of my life I’d been listening to Elvis’ music, and the second part has been working with ?uest and The Roots, so I guess I was qualified to work on this collaboration! I was in a unique situation in that I know Elvis’ back catalogue inside out, and am intimately familiar with the way The Roots and ?uestlove work. The challenge was to turn the idea of them working together into a true collaboration, rather than The Roots just being Elvis’ backing band or him singing over beats. For me it was obviously a lot of fun to meet Elvis. If he’d asked me to engineer an album for him I probably would have been too intimidated to even attempt it, but I somehow knew how to make the combination of him and The Roots work. If I had contributed to the making of some kind of failed Elvis Costello record, I would have never forgiven myself.”

THE PATCHWORKER

Mandel was the unsung hero at the centre of the entire process, and he worked endless hours piecing different elements together, constructing and deconstructing the tracks, suggesting and working on arrangements and getting the sonics right, in a process that mirrored the manner in which The Roots and he had been working for many years. In addition, Mandel put his encyclopaedic knowledge of Costello’s previous work to good use. He ended up with a co-writing credit on 13 of the 15 songs on the deluxe version of the album. For Mandel, as a Costello fan, this was a dream come true.

“Elvis wrote all the lyrics for the album,” explained Mandel. “And Ahmir and Elvis co-wrote the music, and I provided the initial ideas for some of the songs. For example, Wise Up Ghost is based on a loop of Elvis’s song Can You Be True from his album North (2003). Similarly, the song Tripwire is based on a loop of the intro of the song Satellite from Spike (1989), which I had processed to the point where even Elvis didn’t recognise where it came from. Many of the loops that provided the start-off point for the songs were based on samples taken from when Elvis played with The Roots on the Fallon show. They played six songs together over three visits by Elvis, and we were able to cull a bunch of the songs from that. Everybody has been focussing on Elvis re-using some of his lyrics, but it’s also really interesting where the music for these songs came from.

“The making of this album was incredibly collaborative. As an engineer you can suggest things without saying anything, just by selecting what you play to people, or editing or processing things, and people will react to that. And, of course, you spend many hours on your own with the session, working on the sounds and changing things around and so on. After having recorded or been given many ideas and parts of songs, I was left by myself for much of the time to make many of the writing and editing decisions, and trying to make everything work.”

UP TOP AT 30 ROCK

While many of the origins for the songs on Wise Up Ghost came from individuals working things out by themselves on a computer — whether that be Mandel sampling Elvis songs or Elvis laying down his ideas in Garageband — the team were eager for the album to sound as live as possible, and not entirely like a hip hop cut-and-paste affair. For this reason, Mandel recorded live playing as early as possible, usually going for whole takes. Amazingly, the vast majority of the recordings were done at The Roots’ tiny rehearsal room at the NBC building in the Rockefeller Center. The famous address — 30 Rockefeller Plaza in downtown Manhattan — is why they tend to refer to the studio as 30 Rock, even though its official name is Feliz Habitat Studios. Mandel clearly took pride in the fact it’s a very unlikely place to make high-end recordings. He sees it as another illustration of great recordings being about the music and the people, and not about the gear or the studio.

Mandel: “30 Rock is the most ridiculous studio in the world. It’s not really a studio. We have nothing in it, no outboard, and very few plug-ins. It’s the place where The Roots rehearse every day, and it’s set up so I can record what they are doing. It’s part of my job on the show. The equipment we have at 30 Rock is so minimal, it’s a joke. It’s just a computer, a few microphones and a Digidesign Control 24. The studio is very small, about the size of a New York apartment kitchen. We have a main room, and a room for the drum kit, and a lounge at the back. The two keyboard players, the percussionist, the bass player, the guitar player and I all fit in the main space, and Ahmir is in the room next to us. The main door leading into the hallway is soundproofed, as is Ahmir’s space, not for acoustic reasons but to make sure we’re not bothering people outside! We are really minimalist, almost to a fault. In fact, we prefer this kind of uncomfortable setting, because it means that you do what you have to do and then you get the hell of the room! It’s a kind of guerrilla approach to recording.

“Insofar as the sound is concerned, I think it boils down to there being a very short signal path between the source and the hard drive, and not using many plug-ins. I always try to keep my eyes on the main prize, which is that I had Elvis Costello and ?uestlove in the room, so how many plug-ins would I need to cover up what these guys were doing? They are virtuosos. Even if the pizza boy were to stick some horrible microphones in front of them, they would still sound good. The whole point of ?uestlove is the power and drama and clarity of the sound of his kit, which is completely unprocessed. I was taught to record things as truthfully as possible, trying to record the actual sound you want down to tape, and I still follow that advice. When I hear that overblown high-end digital stuff, I’ll change it, or I won’t use it. At the same time, I’ve given up on trying to make things sound analogue or digital, or being attached to using certain gear. It’s not about the equipment.

“30 Rock provides us with a very close, direct sound, which is what Ahmir and I prefer. It was the same thing with Elvis. When I recorded him in Vancouver, my only intention was to close-mic the f**k out of him. On all my favourite albums by him, he’s right in your face. So we close mic, and then have a signal chain that’s as short as possible. When Paul McCartney recorded his first solo album, he just plugged the mic directly into the back of the tape machine. That makes the most sense to me. The job of an engineer is for the most part to replicate what is being played in front of him for the eventual listener, who will be sitting in front of a left and a right speaker, experiencing what it sounds like if he or she was actually there. Close miking makes a lot of sense, but, depending on what you’re going for, so does more distant miking. Ahmir and I have found over the years that you get a more accurate drum sound by not having a snare mic right next to the snare, but a few feet away. We’ve been experimenting with having more space between the mics and the drums, though in 30 Rock I can’t achieve much of that. And in the end I’m usually simply thankful that the mics are working at all, so whether or not they’re three feet away is not my main concern.”

WHAT MATTERS

In keeping with his ‘gear and recording space don’t matter’ ethos, Mandel was reluctant to divulge too much about his signal chains, but after some gentle coaxing he relented, and provided some details, also of the sessions in Vancouver and Philadelphia.

Mandel: “There are many Shure microphones at 30 Rock, perhaps because of some kind of sponsorship deal, so that’s mainly what I used. Everything went through Avid mic pres. I had a couple of mics on the kick drum, Shure Beta 52A on the front, and the other being a AKG D112, placed where the pedal hits the skin so you get a combination of the kick and the snare. This has long been one of our favourite mics to use for hip hop, because it gives you a really crisp sound. It’s one of our secret weapons. Then I had Shure KSM137 condenser mics on the top and bottom of the snare, a couple of Shure KSM313 ribbon overhead mics, and Beta 98s on the floor and rack toms, plus I put a Shure SM57 behind ?uest for a real garbage-like room sound. There’s no space to put a mic in front of him!

“For the bass and the guitar I used mostly Shure SM78 mics on the cabinets, though I recorded DI as well. The keyboard sounds came mostly from the Yamaha Motif XF8, recorded with a DI box, and then treated with Line 6’s AmpFarm, which is our favourite plug-in. That incredible piano sound on Puppet, for example, I could lie and tell you we recorded it in a church, but it was the Motif, recorded via a DI!

I went to Vancouver to record Elvis at a studio there called Crew, where I tried several different mics on him, and ended up using a prototype CM12SE from Advanced Audio. In Vancouver, Elvis played real Wurlitzer and real Fender Rhodes. When Elvis came later to record in 30 Rock I tried the CM12SE on him again, because I paid 700 bucks for it, and I was ‘going to use it!’ But it didn’t have the same magic as when we used it in Vancouver, probably because the mic was too bright for the room in 30 Rock. So I switched to one of our regular Shure mics, the KSM9, and it sounded more natural. Finally, I recorded the horns in ?uestlove’s Philly studio, using Neumann U87 mics going through Focusrite mic pres. The strings were arranged by Brent Fischer and recorded by Rafa Sardina at Conway Studios in Los Angeles.

“Of course, you can use exactly the same gear that I used, but you won’t get the same sound, because you need Elvis, ?uest, and The Roots for that. Gear is important, and there’s an art or science to using it, but I am not a gear head, and I never was. I am more a musicologist than a technician. For me other things are more interesting, like how to conduct a session, how to handle players, how to get good arrangements, and so on. The reason I do this for a living is because I love listening to music and listening to records. The technical side is something you have to do, but making music is something you want to do. Of course, I prefer great microphones to bad ones, but you don’t always have great microphones around, and it’s more expensive to rent a real piano than to use a sample. Remember, we had no budget. So you learn to work with what you have.

“In terms of conducting a session, even though we have the technology to loop everything and applied a lot of the cut and paste hip-hop aesthetic, I would still ask the musicians to play full takes. Sometimes someone would say, ‘I’ve just played this part for two minutes, can’t you sample eight bars and loop me?’ And my response always was, ‘No, I need a full take, because it allows for small variations to happen, or even for mistakes to occur, which can give us new ideas. One of our main principles is that many of the greatest things happen when you make mistakes. Playing full takes really helps to thwart that ‘digital thing’. Ahmir is the one to credit for that. He’d been making straight hip-hop in Philly for years, and even then he was playing full takes. It’s part of what makes him unique.”

We prefer this kind of uncomfortable setting, because it means that you do what you have to do and then you get the hell of the room!

GUERILLA MIX

After several months of recording and editing and cutting and pasting and rearranging and trying things out during the end of 2012 and the beginning of 2013, Mandel set about mixing the album. In keeping with his and The Root’s wilfully irreverent minimalist attitude to gear and studios, he mixed almost the entire project at 30 Rock, on a pair of old JBL monitors, and after he blew those out, on some Genelec 1032A monitors. In keeping with the modern DAW approach, Mandel already mixed the album “from day one; the moment we put down the first couple of notes I tried to figure out how loud they should be.” But nonetheless, a final mix stage involved Mandel locking himself in the 30 Rock rehearsal room during down time for many hundreds, if not thousands, of hours.

Mandel: “The process depended very much on the song. Mixing The Puppet Has Cut His Strings, for example, was very quick because there literally are no effects on that. Elvis recorded the vocals on his computer, which created the compressed vocal sound, and the music is just drums, bass, and piano — I added no plug-ins at all. To me, it’s one of the best-sounding songs on the album, with all the space and depth we were after. That’s when you realise it’s just ?uestlove, Elvis, and the other players; not me. But other songs have tons of plug-ins, mostly EQs and compressors. We were trying to keep things as organic as possible and only use effects for a reason. Like on Tripwire, I put some heavy delays on Elvis’ vocal, because it made it blend in better with whatever else was on that track. I was also trying to craft the sounds based on what he was singing about. The effects are supposed to complement and augment the song, and not attract attention to themselves.”

While Mandel gives off an air of indifference to what gear he uses, or where he records, he clearly agonises extensively over the end result. He was outed recently by ?uestlove who was browsing the Fallon show iTunes library, cruising for songs to play during commercial breaks. Mandel: “While doing this he comes across mix after mix after mix of the songs of the album we did with Elvis. There were like 100 versions of Walk Us Uptown, and 150 versions of Come The Meantime, and he came up to me and asked, ‘Steven, what the f**k is going on?’ So I tried to explain my process to him.

“Once I have the sounds to a decent standard and a balance that I like, I’ll print the mix, because it makes it more real to me. It puts a sort of pressure on me, and it allows me to gauge the mix as a whole, and also whether there are details that need correcting that I may not have heard or have not allowed myself to become aware of. My other trick is to print a cappella, instrumental and TV mixes before I print the main mix. These allow me to hear things I can’t hear in the full mixes. My main criterion is whether I think I can live with a mix for the rest of my life.”

Judging by the reception to Wise Up Ghost, Mandel has no reason to worry or to forgive himself. The album has all the signs of going down to posterity as a masterpiece.

RESPONSES