Tony Buchen: Recording With Attitude

Tony Buchen epitomises the self-made indie producer making records with plenty to say. Here he discusses the art of production in his own words.

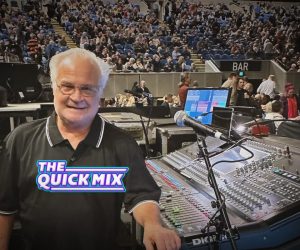

Photos: Nick La Rosa

I was a musician first and foremost. I had no aspirations to be a producer. Then, back in 2000 I was making records with my band at the time, The Hive, and I felt out of control — I didn’t like that feeling. I was at the shoulder of the engineer all the time. I knew exactly what I wanted to hear but I just didn’t know how to execute that vision. So I began to learn the craft of production, programming, and then engineering, with my musicianship always informing what I did.

These days I’m spending most of my time as a producer working with indie artists. It’s really indie-focussed, with the occasional major label gig. But even then, there’s not much difference. Maybe there’s a bigger team on board with the major label artist but the way I work, I always put the musicians first.

HAVING AN AESTHETIC

People ask me what’s the career path to being a good producer. The first thing is: what’s your aesthetic? Because if you don’t have a sense of aesthetics, you can’t be a producer. You might be an engineer, but even good engineers, who don’t call themselves producers, still have an aesthetic as well.

If you look at [The Beatles engineer] Geoff Emerick, he’s a great example, because clearly he was doing so much movre than engineering in those sessions. He was bringing what we consider our modern sense of what a producer is. And he transitioned into being a producer relatively easily. If you listen to Elvis Costello’s album Imperial Bedroom, he produced that and he produced Split Enz’s Dizrhythmia. You listen to those records, production was such a natural crossover for him because he had a deep sense of aesthetics. He got it.

THE CRAFT

Training is hugely important. I trained myself, or, more to the point, I sought out people who could train me. In the early stages of my production career I always insisted on working out of the best studios — I was obsessed with it, I insisted and somehow bands always managed to find the money.

I primarily worked out of [the now closed] Electric Avenue Studios in Sydney; Phil Punch’s room, which was a one-off, magical place. Phil has the deepest collection of vintage studio gear in the country, in fact, one of the deepest collections in the world. But the point is, the first eight or 10 records I ever produced, I had either Phil or one of his guys engineer and I was like a hawk. I asked questions about every click, and after five or six records I developed the confidence to start engineering myself.

Phil Punch was my unofficial mentor. He probably wouldn’t even consider himself that, but I’m very grateful for his input and I learnt the Abbey Road method. He taught me the proper way, and once you’ve got that down you can mess with it.

I have an intrinsic belief that if things are done well — purposefully, intentionally, skilfully — then you’ll always have a role and relevance. But I’m not saying you need the best gear and the best studio to really cut through and produce something epic. Take Wally De Backer [Gotye] as an example. Look at Wally’s dedication; look at the fine detail, the hours, the years, the deep sense of aesthetics, of going deep into record collections and the discovery evident in that. It just speaks for itself.

I don’t think you’ll find many world-beating songs done on a whim. I believe that what really does cut through is coming from a very accomplished place. Even cheesy, hyper-buffed pop; even that comes from an accomplished place. Years ago my publisher was asking me to write more pop, but my take was always ‘leave that to the guys who are doing that as a craft, because they’re always going to win.’

APPROACHING A SESSION

I endeavour to run a session where the artists don’t know they’re recording. And so often they’ll remark, ‘Are we recording?’ I won’t even get on talkback. My philosophy: they can start whenever they want, and then you get those magic moments free of self-consciousness. No one’s counting in, there’s no click track. Of course, I will work to click if needs be but I’d rather edit between fluid sections than have a set tempo.

In the end, musicianship is everything, especially if you’re gunning for a type of sound.

I had an absolutely revelatory moment in my career after I spent five years asking drummers to play like Joey Waronker. Joey’s work has always been a personal favourite. And then finally I got an opportunity to work with him, which lead to an opportunity to hire him on a session I was producing. It was the equivalent of having Mavis Staples sing a gospel/soul song. ‘I need that Mavis Staples sound.’ ‘Okay we’ll get Mavis.’ There it is. Done!

WORKING IN THE US

People will ask: ‘Why do you go to America? Can’t you get that sound here?’ The answer is ‘yes’, but it’s not made as easy for you. When you’re sitting in the studio and the assistant has just come off working with Nigel Godrich, the drummer is in Beck’s band and the keyboard player is from Fiona Apple’s group… these guys’ catalogues are deeper than your own. As a result, you mentally rise to the occasion — you step it up.

That’s why I go to the US, because I want that challenge. I want to feel like I’m in the deep end all the time. There’s nothing like it. The musicians are impatient in a way, because if you don’t get your shit together and give them clear directions they get antsy. I’ve actually had some guys say to me, “look man, I can play anything you want, you just gotta tell me.” No one would say that in Australia. No one’s got that kind of arrogance. But it’s not even arrogance, it’s just a fact: they could.

So that’s a big difference. And what that does to you mentally when you’re calling the shots in a studio session… it’s a very powerful position to be in so you’d better be ready for it. If you’re not, then it’s very disempowering because you feel very inadequate if you don’t step up. And I freely admit there have been a couple of moments where I just wasn’t ready. But so be it. Everyone goes through that in order to get to the next place.

As a generalisation, Americans bring a higher level of urgency and intensity. Here, you’re more likely to need to rev a band up: “Let’s get in there, let’s go!” In America you don’t need to do that. They’re high-fiving each other before they’re even recording — ‘I’m in a recording studio trying to be a rock star and it’s awesome!’ Here, it’s like, ‘I’m cooler than that, I’m not going to do that.’

On the other hand, Australians tend to be far more adaptable and better at problem solving. In America there’s a ‘right’ way of doing things, and that leaves little room for improvisation. Australians don’t play that game, we’re jacks of all trades getting something cool happening. And I think Americans admire that.

For example, I’ll walk into the studio and the engineer’s talking at me: “You want the M88 on the inside of the kick and the FET 47…” And I’ll cut him off, “No. Let’s put an omni mic on the inside of the kick and a ribbon mic five feet away.” And they’re like, “Whoah, this Aussie dude, he’s crazy!”

Maybe some day fans will be able to hold the artist in the palm of their hands like Princess Leia and have them perform a song… but it’s still a recording and without the recording you’ve got nothing

WHERE’S THE MONEY GONE?

It’s no great secret that the Australian music industry is hugely competitive — as it is everywhere. There’s huge pressure on album budgets and in my experience we’re spending less than we were 10 or even five years ago. There’s a real pressure to produce the goods on less.

This can’t go on forever. When I started, you might have a $70k budget, then a $50k budget and now a $30k budget. That doesn’t mean in five year’s time it’ll go to $5k. I don’t think that’ll happen. My view is it’ll stop at around $25k, because any less than that and you’re working out of your bedroom — you’re not going to have a producer.

I’ll do my best to reinforce this message to the managers and record label representatives: the recording is an investment in their artist, not just that but the best investment you can make. That recording, that artefact — be it digital, vinyl, CD or anything else that might come along — that’s they’re greatest asset and their best marketing tool. You can have the best photography, greatest video clip, and an amazing live show, but if you don’t have that recorded artefact you don’t have something to leave with an audience. Maybe some day fans will be able to hold the artist in the palm of their hands like Princess Leia and have them perform a song… but it’s still a recording and without the recording you’ve got nothing. Let’s not forget, we’re no longer just selling records anymore, the label and manager will recoup in other ways. Labels have been slow to realise that. They’re coming around now.

TRIPLE J GAME

The landscape of Australian music making is dominated by this entity we all know as Triple J. Which is the most wonderful, amazing thing. We have a public broadcaster with national reach and, if you get on it, it’s like riding a wave of success. Not guaranteed success, mind you. Nothing is guaranteed in music, especially on radio. I’ve had songs that have been in the Triple J’s Top 10 high rotation that year and not made an impact commercially or even created a vibe for the band — it’s really about whether people connect to the song.

Triple J is not the be all and end all, but it is the most amazing access point. The problem is: we live in such a big country with such a sparse population that you don’t have much else. You’ve got the community radio stations which are hugely important, but there’s a big gulf between their impact and Triple J’s impact on the touring career of an artist.

As a producer you’re sitting there thinking: ‘I want to get them on Triple J’ — it’s something that’s in the back of every producer’s mind in Australia. Now I’m at a point where I know what needs to be done to at least give a song a fighting chance of being on Triple J.

Broadly speaking: it’s about giving a track attitude. How you do that is up to the individual. It depends on the track but it might be distorting a vocal in a certain way that can imbue it with some incredible excitement. Or it might be by EQ’ing the return of a delay — it’s amazing what you can do to the character of a vocal.

So it’s about understanding the emotion of a song and the attitude and then executing it. If you hear it on radio, does it leap out of the speakers? And remember: the guys programming radio will be walking down the hallways of the station and be constantly listening to the on-air programming, because it’s always beaming throughout the station. They’re not listening to your song on a CD or a laptop — they’re listening to the radio through their station’s compression, through every different type of speakers in the world, with environmental noise all around, and with people talking at them. That’s the listening experience, so your song has to cut through and say something.

And yes, the vocal is the crown jewel in the mix, but it may not necessarily set the tone. You can have an intro to a song where you strip it back, mute everything except the drums and distort the f**k out of them and then blend that distorted sound into the opening of the track. ‘Woah! What’s that?’ It wakes you up.

Geoff Emerick in the ’60s, Todd Rundgren in the ’70s and Bob Clearmountain in the ’80s… You can’t just come in with nothing and then innovate. These guys were schooled, they trained, and then they innovated

PUTTING IN THE (10,000) HOURS

I’m a big believer in Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule. As Gladwell points out, The Beatles performed live in Hamburg over 1200 times from 1960 to 1964, amassing more than 10,000 hours of playing time, meeting the 10,000-Hour Rule. He also demonstrates the rule at work with Bill Gates and others. Simply put, to master an art you need to put in the time.

I’m also an avid student of studio history and it’s fascinating to observe how the real innovators went about their craft. The likes of Geoff Emerick in the ’60s, Todd Rundgren in the ’70s and Bob Clearmountain in the ’80s, were genuine innovators but to be an innovator you’ve got to know the craft first. You can’t just come in with nothing and then innovate. Maybe one in a million will fluke it. These guys were schooled, they trained, and then they innovated. And I would like to feel that I’m of that school. I’m certainly not at their level yet but I hope to be one day.

Not to say the kids don’t come up with cool things and to be honest I have no qualms in using ideas from demos that I think sound great — I’m not the first to say it, but if it sounds great, use it. And they’re surprised: ‘No you can’t do that!’ ‘Yeah you can. You can do anything dude!” And that is the difference about working now than in the ’70s or ’80s.

The difference is that we have a full, enormous palette to draw from. And that to me increases the value of a producer. Because the kids don’t know where to start. I know where to start, I know where to draw from and I can confidently assert ‘I need to draw on a ’60s technique for the drums on this.’ Or on another occasion I’ll want to distort the vocal in a different way with a plug-in.

So it’s about a palette and how you use that broad palette. It’s a challenge. Because in the ’60s all you had was four tracks, maybe. These days you have to force the limits on yourself.

RESPONSES