Songs of The Volcano

A virtuoso guitarist, a field recordist and a filmmaker sweat it out with locals, laptops and ukuleles in Papua New Guinea, while a nearby volcano rumbles in disapproval and buries everything in ash.

Papua New Guinea… The name conjures childhood memories of masks and spears mounted on an intrepid uncle’s wall, images of mud-men and exotic birds on the cover of National Geographic magazine, and ripping yarns of cannibalism, cargo-cults, and crazed Japanese soldiers nervously emerging from the jungle to check the progress of the war.

As with all tribal cultures, PNG has a repertoire of indigenous music that dates back to the dawn of time and has occasionally tempted Australians to cross the Torres Strait to record or otherwise interact with it – either as ethnomusicological research recordings like those made by Drs Gordon Spearritt and Robert MacLennan from 1965 to 1975, or as collaborations such as Not Drowning, Waving’s 1990 album Tabaran.

But the music behind this story cannot be traced back to the dawn of time. It’s a relatively recent form that began after a Western visitor left behind an acoustic guitar. Like dropping unfamiliar seeds into fertile soil, the indigenous community cultivated a unique musical crop called ‘stringbands’ – complete ensembles consisting almost entirely of acoustic guitars. It’s the kind of music that proves irresistible to a virtuoso guitarist and ethnomusicologist like Bob Brozman. When an informal meeting with field recordist Denis Crowdy, professor of music Phil Hayward and film-maker Phil Donnison revealed they had a common interest in stringbands, the result was inevitable: a musical journey to PNG to perform with the musicians, record a CD, and make a documentary in the process. Denis Crowdy talks about the challenges of making such a recording…

Greg Simmons: Tell us a bit about your background and how you got involved in this project, Denis.

Denis Crowdy: I have a performance degree in classical guitar, and playing music has always been a central part my work. My interest in ethnomusicology, field recording and stringbands developed during a nine-year stint teaching music at the University of Papua New Guinea. In 2000 I moved to Sydney to take up a position at Macquarie University, where I completed a PhD studying a band from PNG called Sanguma – that’s where I met Tony Subam, who engineered some of the songs on this album. Sanguma were playing a version of world music in the 1980s before most people in the region even knew of the concept!

Our professor of music here at Macquarie University, Phil Hayward, had been looking to form an association between a respected Western musical collaborator and non-Western musicians, in order to work on Pacific projects. US-based guitarist Bob Brozman was highly recommended and, coincidentally, was in Australia at the time, so we went and saw him playing at the Mooney Mooney Workers Club. After a couple of meetings we realised there was an obvious convergence of interests, and so we organised the trip…

GS: What instruments were you recording?

DC: Ukuleles, guitars in various states (some in really poor condition, hence Bob’s constant handing out and changing of strings for everyone!), a portable keyboard with built-in speakers, male vocals (sometimes in strident falsetto), then Bob’s guitars – the Kona and National.

GS: What was your approach to recording them?

DC: The main instruments were miked up individually for the initial tracks; the others had to share mics. For example, the guitars playing lead or finger-picked accompaniment parts were usually given a mic each, perhaps a Rode NT1 or NT2, while several rhythm guitars would be huddled around a Shure SM57. In addition to the close mics, I was also using an Audio-Technica AT825 stereo XY microphone to get a room sound to blend all the instruments and create an appropriate musical texture. I tried to DI the portable keyboard but it sounded too ‘close’ and didn’t sit properly in the musical texture, so I ended up miking it with the other instruments.

We then overdubbed some guitar parts, although this was less successful with the band guitarists because they preferred to play in a performance situation. Lots of Bob’s parts were overdubbed at the end of each day, and for those we always used his Neumann KM150.

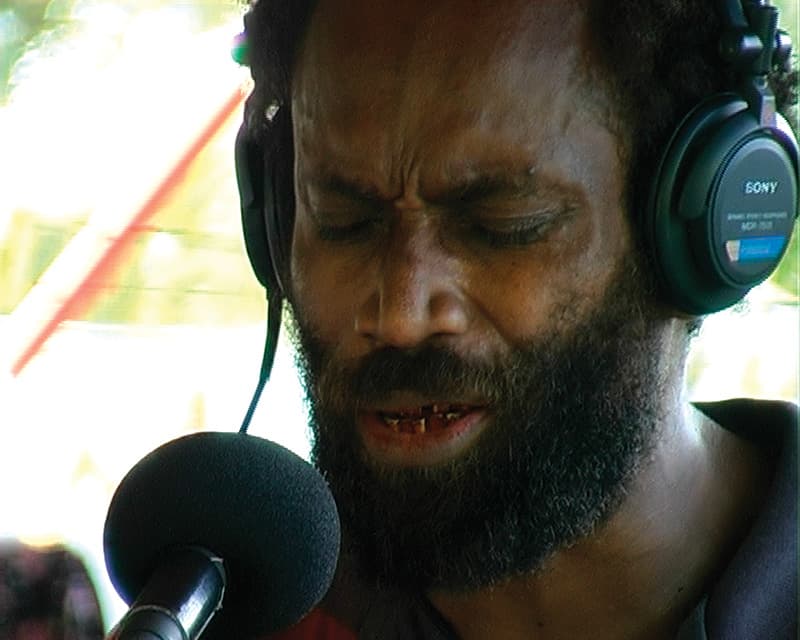

GS: And the voices?

DC: There were so many voices because, essentially, everyone sings as they play! The AT825 picked up the bulk of the vocal sound in stereo. If there were any spare Shure SM58s after miking up the instruments, I’d have two or three people singing into those. Then I’d overdub a main vocal track, just a single track, if things needed thickening.

STRING RACKET

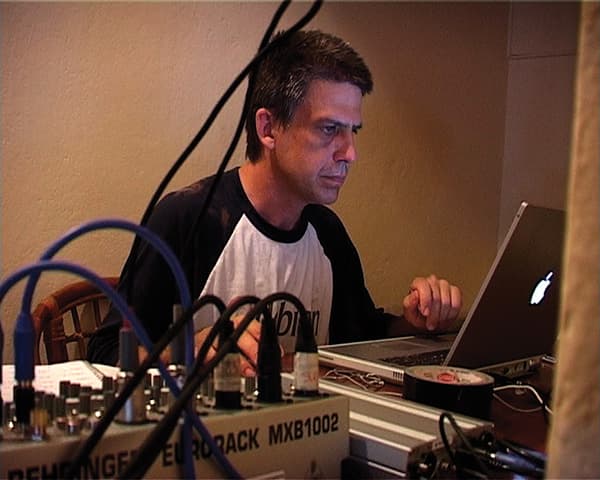

GS: What were you recording with?

DC: A Titanium Powerbook running Cubase VST under OS9 – it worked and was stable, so I kept it simple. For audio input I used a Behringer Eurorack mixer feeding an Apogee Mini-Me A/D converter with USB interface. The Mini-Me’s fidelity is amazing…

GS: You were obviously making multitrack recordings with overdubs and so on, but Apogee’s Mini-Me is only a two-channel device. I assume you were sub-mixing many individual sounds directly to stereo before recording…

DC: That’s right – the hard part was sub-mixing direct to two tracks while in the room with the band. Hardly a good monitoring setup!

GS: Considering your previous experience with stringbands, how did you approach those sub-mixes?

DC: I was aiming at getting a balance of the instruments that represented the best compromise between the natural acoustic sound and what would work on a recording. For example, I would boost and/or EQ a guitar part that was playing a bass line in order to get a bit of bottom end into it while it still existed as a discrete signal, because it would be very difficult to do that in the final mix without affecting the other instruments.

Spreading the voices through the stereo field was also a challenge – sometimes there was such a huge vocal sound filling the room that it was hard to hear what was actually being recorded! So we always did a lot of playbacks along the way to make sure the sub-mixes were right, before moving on.

GS: What were you using for monitoring during all this sub-mixing, recording and playing back?

DC: Headphones only, I’m afraid! Sony MDR7505s; I use them a lot for everyday listening as well, so I know their characteristics. Nonetheless, headphones are quite different to speakers and I think the end result has definitely been affected by that. Next time, I’ll try and take some small monitors.

GS: Did you have any serious problems or equipment malfunctions?

DC: The power went off a few times, causing an obvious malfunction…

GS: …but all of your core equipment – the Powerbook, the MiniMe and the Eurorack – are capable of battery powering. Couldn’t you have run the whole rig off batteries and avoided such problems?

DC: Battery power is great, but sometimes it’s just not practical to be lugging all the extra weight around – especially when you know that your destination has mains power. I decided to leave the lead acid battery for the MiniMe in Sydney because I was carrying too much gear (I wanted it all to fit into a single flight case) and my luggage was already overweight; we had a pretty hefty excess fee.

A blackout was inconvenient but it wasn’t a major disaster because the Powerbook would revert to its internal battery whenever the power went off, allowing me to save the session files and shut down properly.

GS: I assume you were making regular backups of your files…

DC: Yep. I carried a 15GB iPod and dumped the files onto it at the end of each day. I also burnt CDs of the audio, so I had two levels of redundancy as far as backup went.

We had problems with some very low frequency rumblings in the recordings… turned out to be the local volcano, Tavurvur, doing its thing…

HOT SIGNALS

GS: In such a hot and humid climate, did you have any environmental problems?

DC: We had problems with some very low frequency rumblings in the recordings, which we mainly noticed during playback. Turned out to be the local volcano, Tavurvur, doing its thing…

GS: Er, a volcano?

DC: Yep… It explodes periodically, several times a day or so, and then chills out.

GS: Crikey! Were there any fears of an eruption?

DC: No, fortunately. The last major eruption was in 1994. In fact, a couple of the songs on the album lament the destruction it caused of the old town. The volcano still spits out ash; at least a centimetre a day was falling everywhere on the hotel – there was an employee whose sole job was to sweep ash!

GS: Speaking of the hotel… is that where you made the recordings?

DC: Yes. We recorded in a large hotel room – it could probably fit up to 20 people, but with some of the bigger bands we’d have 25 or more in there. It had no air-conditioning, and we had to seal off the windows and door to prevent the ash coming in and ruining the equipment – and the wonderful finish on Bob’s National guitar! The ash is like an airborne oilstone, very abrasive little particles…

GS: Ouch! It must have been stifling in that room…

DC: Yeah, things got really hot in there, probably high 30s to low 40s, and incredibly humid; it must’ve been 90%, about as humid as you can get! We were totally drenched in sweat a lot of the time…

GS: How did the instruments handle it?

DC: The humidity and heat caused all sorts of tuning problems, of course. Fortunately, Bob is a master of sorting those problems out.

GS: Those Titanium Powerbooks run quite hot in my experience, even at normal temperatures. It must’ve been running very hot in that room!

DC: I had a desktop fan blowing on it between takes to keep it cool, but even then the internal fan was going pretty much the whole time – it didn’t seem to increase the noise floor in the room, so I didn’t worry about it. Despite the heat, the laptop didn’t miss a beat! In fact, I’m still using it to this day; although I’ve moved to a Linux OS.

GS: I think you were quite brave to take a laptop-based recording rig into such a technologically-hostile environment. Would you do it again?

DC: Absolutely. I was particularly impressed with the way the Powerbook kept working under conditions outside its design scope. I took a portable DAT as a recording backup, of course, but didn’t need it. We recently recorded in Norfolk Island with a more powerful Powerbook and a MOTU 896 interface, no problems there, either. In fact, so far I’ve had no problems at all using laptops for field work…

It had no air-conditioning, and we had to seal off the windows and door to prevent the ash coming in and ruining the equipment… things got really hot in there, probably high 30s to low 40s, and incredibly humid.

RESPONSES