Rupert’s Word: More About Noise & Bandwidth

More About Noise & Bandwidth

I concluded my previous column with two simple experiments you can do that demonstrate a) our awareness of sounds above 20kHz, and b) the ear’s ability to discriminate in favour of a ‘wanted’ sound in the presence of a much louder ‘unwanted’ sound.

We need to be cautious about claims resulting from such simple experiments. But clearly the first experiment suggests that we have awareness of sound above the conventional 20kHz brick wall. There are a number of theories about how we detect this sound:

(a) The body, being comprised of the same cells as are found in the ear, is just one big ‘ear’ but with poor communication to the brain, or (b) there is a complete inner ear cell without a diaphragm, behind the obvious one, and this has response up to at least 100kHz.

The truth is that, to my knowledge, we have not ‘proved’ how the mechanism works. If anyone is working on this, I’d be delighted to find out more.

There is evidence that the presence of incredibly small quantities of the ‘wanted’ signal (e.g. true harmonics of musical instruments) enhance the listening experience whilst incredibly small quantities of ‘unwanted’ signals (eg, noise, high order harmonic distortion, non-harmonic switching ‘splat’ or clicks) have the opposite effect – producing a puzzled and tired brain response that is trying to relate this unnatural sound to its in-built data bank of real sound acquired from the natural world around us. (Many people, of course, have no such data bank and their brain thinks CDs are the real thing!) Some time ago Professor Oohashi and his team, from the Institute of Mass Media Education in Tokyo, read a paper to the New York AES: “High Frequency Sound Above the Audible Range affects Brain Electric Activity and Sound Perception” (AES preprint no. 3207) He claimed that extension of the frequency range beyond audibility was beneficial to sound quality and produced brain electrical activity from the area associated with pleasure, etc. Read our interview with Rupert Neve for more.

I visited Professor Oohashi in Tokyo and was treated to an impressive series of demonstrations comparing music recorded and reproduced with:

(a) Very wide bandwidth;

(b) Bandwidth restricted to 20kHz;

(c) The same material through standard Compact Disc;

(d) A new wide band one-bit digital CD system designed by JVC.

There is no doubt that the wide bandwidth is more enjoyable.

Music actually sounds sweeter and warmer when high frequencies are extended (distortion and noise-free) beyond audibility. No obvious sensation of a stronger or more aggressive high frequency response. I was able to relax and stop ‘listening’ — just letting the magnificent sound flow over me.

This accords with opinions from many well-known ‘golden ears’ of the industry. For example, George Massenburg has more than once gone on record (unintentional pun!) to say that he likes listening to an LP for relaxation. Having worked with sound all day, he prefers the LP; a CD with exactly the same music makes him restless and unable to relax. An LP in good condition, played with a good cartridge, can have a response well beyond 20kHz.

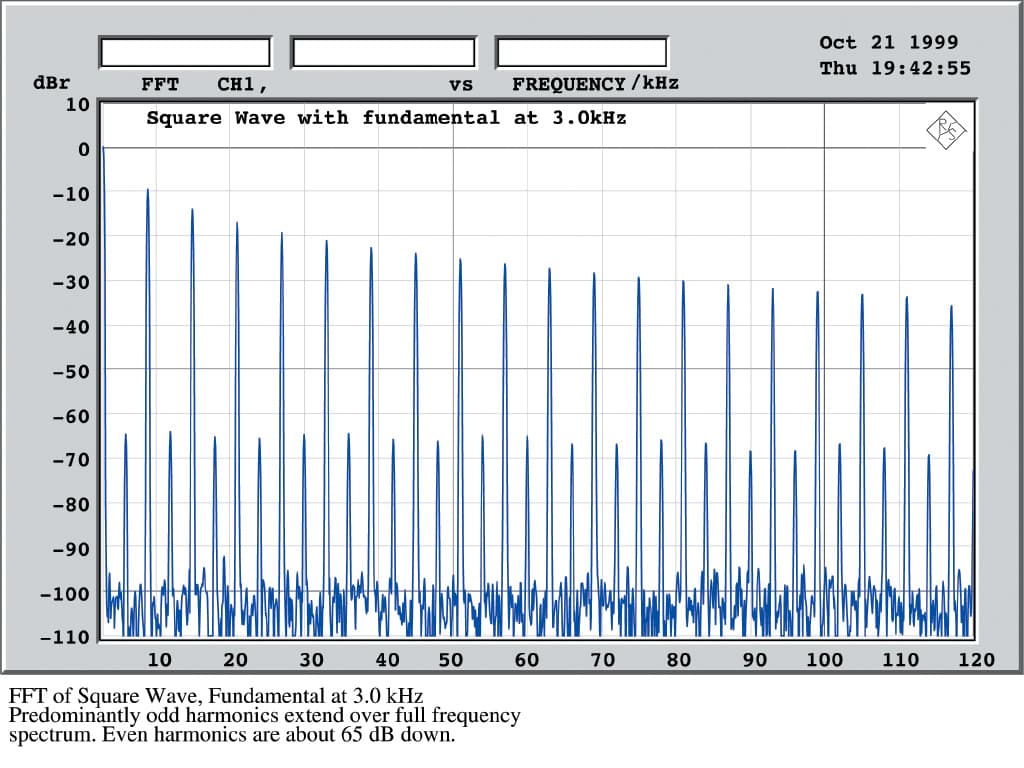

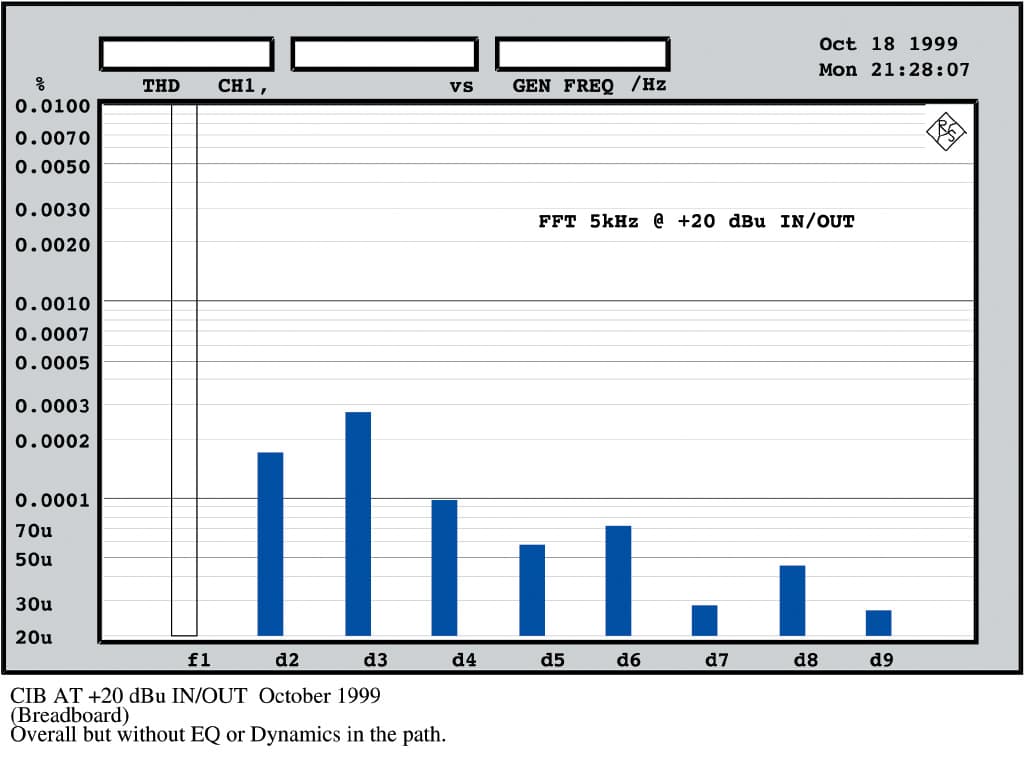

But it seems to me that there is more than frequency response, as demonstrated by Professor Oohashi, which plagues the standard CD. The digital process is always badly flawed by non-harmonically related switching transients which are dumped in the critical area above 20kHz, resulting in a substantial increase in noise beyond audibility (where, it has been thought, it does not matter).

The fact that digital is limited to 20kHz or so is, to me, less important than this distressing signal break-up, because it means we’re back to noise. In my previous column I discussed the many types of noise, and their effect on the sound we hear. Noise that is part of a performance, such as the sound of an artist breathing, is not necessarily bad and in fact authenticates the performance, making it sound more realistic and believable. But the non-harmonically related switching transients of digital audio certainly belong in the category of ‘all bad’ noise!

I like the (in part) American Heritage definition: “noised, noising: To spread the rumour or report of [From Old French, possibly from Latin ‘nausea’.]” Add, if you like, Rupert’s plain English interpretation “Nausea; it makes me sick!” (But unlike Ludwig Boltzmann, who I discussed in my previous column, I don’t feel the need to commit suicide over it.)

Some months ago another consignment of accumulated junk of mine arrived here in Texas, from various places where it had been stored for years in the UK. I found some old 78 RPM acetate recordings I had made around 1948 to 1950, more than 50 years ago. They are noisy and have quite limited response, probably not exceeding about 10kHz. But they sound great. I’m sure this is partly subjective (“Did we really do that?”) and possibly there is a deeply embedded memory of the location and what it really sounded like in the flesh.

We (my partners, Gerry, Alf and I) used to record male choirs, brass and silver village bands, amateur operatic productions, children’s concerts, music festivals and the like in Devon and Cornwall (South West counties of the UK), hoping to sell discs to the performers. We became quite a feature of the local scene, and it was considered prestigious for our ‘Recording Van from Plymouth’ to be present. One local paper, writing about a school concert, reported: “The curtain was waiting to be raised: there was an excited buzz of conversation; the RGA (Rupert Gerry, Alf) microphones were in place to capture youthful talent and the hall was filled with expectant mothers anxiously awaiting the arrival of their young”. (I’m not sure that our microphones succeeded in all that was expected of them!)

Capturing recording and reproducing sound is not merely a matter of devouring equipment specifications – the meat and potatoes, as it were. We have to know and understand the technology we are harnessing and be skilful in its use. But far more important is the vision for what we want to do and the perspective we bring to the feast, which frees the creator in us to produce a sound of beauty which is a joy for ever.

I don’t think that we have ‘proved’ anything with our simple experiments from my previous column, but there is abundant evidence which suggests there is a great deal we don’t yet understand.

In his letter to the Colossians, St. Paul says:

Colossians 1:16 & 17

16. For by him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things were created by him and for him. 17 He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

Let’s keep open minds, go on seeking perfection and developing a reliable point of reference which holds together.

RESPONSES