The Long & Winding Road: Recording The Whitlams

AT’s Editor, Andy Stewart, provides a very personal account of recording The Whitlams’ new double album Little Cloud & The Apple’s Eye. Sit back for a year-long ride through multiple cities, studios, overdubs, mixing sessions… and a leech.

Recounting the story of an album that has taken a year to complete, involved half a dozen studios, thousands of recording, mixing and mastering hours and several dozen green chicken curries is a difficult task, one that I hardly know how to begin.

It seems like a lifetime ago now that I was invited down to a pre-production rehearsal at Tim Freedman’s house in Stanwell Park to meet the main protagonists and get an initial feel for the new songs and what might be involved in recording them. It was a very informal get together from my point of view. My good friend J Walker, who’d been asked by Tim Freedman to produce the record, had already been holed up with the band for a week by the time I arrived, and the ‘shabby edges’ were already beginning to show on a few faces, even though the studio sessions were still weeks away!

The production of a Whitlams album would obviously be a major undertaking. My gut feel was that it would be an interesting project, provided the personalities involved were compatible enough to sail into the unknown together and survive the stresses and strains of the journey. But making a prediction about how everyone might get on based on this one meeting was nigh impossible. So I looked back on two decades of memories of nightmare sessions, sleepless weeks and countless studio dramas… and then said ‘Yes’ to the project… like the glutton for punishment that I am. I decided to hop on board for the first leg of the trip and reassess the situation when we reached landfall five days later. That was a year ago now, and we’ve only just rolled up the sails and stepped onto dry land.

UNCHARTED WATERS

For me, the album really began around schoolies week 2004 – I remember it only because the ‘retreat’ in Byron Bay, where Tim, J and I stayed, was surrounded by pissed and sunburnt teenagers who did their best to make us feel welcome by staying up 24/7! The clear and peaceful air of Byron was filled of an evening with the sound of crickets, wind in the sheoaks, screaming and yelling and the smashing of beer bottles! Throughout most days of this final week of pre-production it rained like I’ve never seen rain before. It was like someone had tipped the world upside down, and it gave Tim and J the perfect opportunity to sit around the keyboard deliberating over lyrics and song structures, eating macadamia nuts and drinking tea. My days mainly involved clearing my mind, avoiding loud music and contemplating the recording road ahead. I’ve never been a great one for listing theoretical recording chains or drawing band setups, and most of the albums I’ve recorded I’ve also produced. I’ve always been far more interested in getting under the skin of the songs and ‘hearing’ them as a finished product as early as possible. So my time was mainly spent listening to the songs in their infancy and soaking up the air around them; getting a feel for what they were becoming without getting too involved in the ‘production’ – something I promised J I’d do my best to resist! By the time we got to the studio the ‘sound’ of the record was already in my head which, for me, is a far more effective way of preparing for the first session than any supposed ‘time saving’ plots and lists that I might have conjured up.

Living in the house together for that week was actually one of the most significant album preparations I’ve ever had the luxury to be part of. Although it might have seemed a waste of time to an outsider, for the three of us (and particularly yours truly), it created a friendly and relaxed atmosphere in which each of us could gain the trust of the others, so that by the time we hit the studio, a bond had been established. In fact, there was one specific incident that constituted the best possible preparation for any big production…

The incident involved a visit to a friend’s property in Mullumbimby that was mostly covered in rainforest. Throughout the humid afternoon and into that evening Tim, J and I traipsed up and down its steep slopes, taking in the spectacular views and drinking from the freshwater creek that flowed through the property. After an exhausting day we piled in the car and headed back to Byron, desperate for something substantial to eat. We wound up in a fancy new restaurant where we proceeded to order half the menu, paying little heed to the cost at the end of the night.

Everything was going well… until the ‘incident’. In the middle of our unsophisticated demolition of a cheese platter, something landed on the floor under our table. I have no real recollection now how it was I came to notice it, but there, to my horror, in plain sight of half the restaurant was a leech the size of a squash ball! Stunned, each of us began checking ourselves for bite marks but none of us could work out whom it had fallen off. Then, in a moment of adolescent behaviour befitting schoolies week, Tim picked it up and placed it on the cheese platter (next to the brie from memory). Over the next five minutes the three of us laughed ourselves sick as we watched the leech search, anemone-like, amongst the leftovers for another bite to eat.

But then everything fell apart. Hilarity turned to terror as Tim decided to pretend the leech had, in fact, been served to us (in retaliation for an earlier argument with the waiter over the freshness of the cheese platter – which Tim was convinced had been microwaved). The leech was positioned alongside the quince paste (which looked uncannily similar to the leech), the waiter was called over, the ridiculous cock&bull story retold and the mortified waiter took the plate back to the kitchen. Moments later the owner of the restaurant came out and sat at our table… Things got tense. He quickly discovered that our story was about as watertight as an upside down U47, and asked us to leave. We happily obliged, fearing for our lives as the chef (who unbeknownst to us had watched the entire incident from the open kitchen) seemed inclined to want to leap the serving bench and throttle us! We were wholly embarrassed by the incident (though not wholly contrite), but we’ve continued to laugh about it for the last year…

MAKING TRACKS

The initial tracking session took place at Phil Punch’s Electric Avenue Studios in Sydney – the facility that spectacularly rose from the ashes of ‘Milk Bar Studios’ – and although everything in the place was new to the premises – right down to the wiring in the walls (apart from the Neve console) – the studio itself was the one thing that was familiar to me, having been involved in Milk Bar’s initial construction and several of its recording sessions thereafter… before the milk ran out and the police moved in.

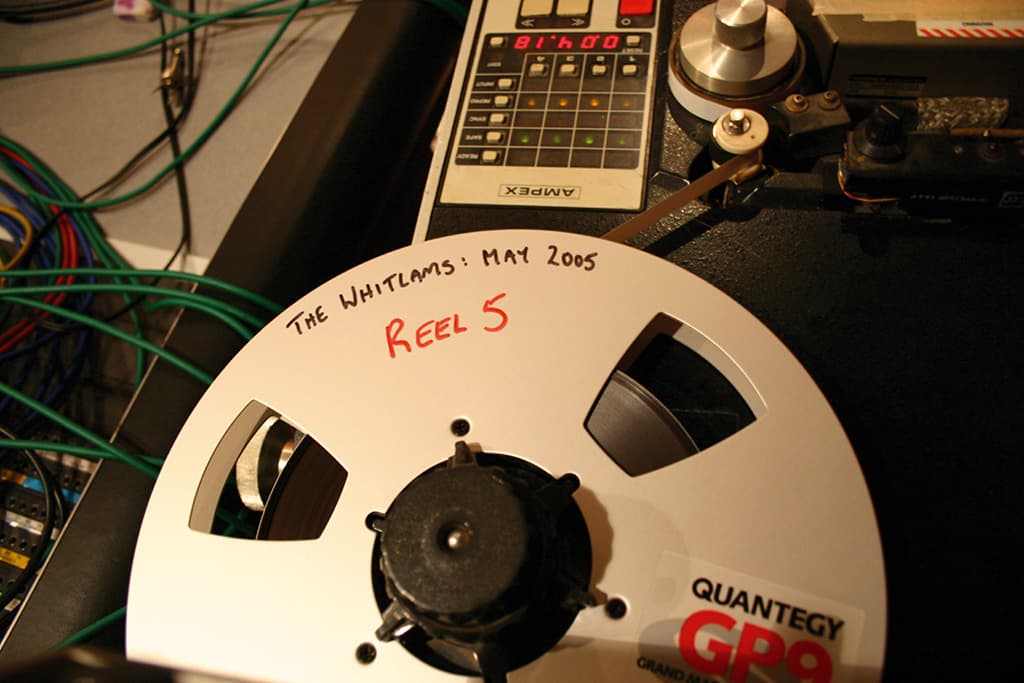

The recording philosophy for the Whitlams album was pretty straightforward: record things well to the studio’s beautiful two-inch Ampex 24-track tape machine, with an ear for something a little less ‘glossy’ and ‘produced’-sounding than perhaps had been the case on previous Whitlams albums. J and I were pretty convinced that drier drums, less hype and more intimacy were something to aim for in the recording phase, in order to expose Tim and the band’s natural ability to play as a group. Overdubs would then be sparingly added to reinforce the band tracks without swamping them in layers of fairy floss that so often wind up placing a wall between the intimacy of the initial performances and the listener. To that end, the aim was also to resist the temptation to add conventional brass and string arrangements, and leave some of that space for backing vocals.

The recording phase nearly always revolved around the whole band (often with J on acoustic guitar) playing live takes to two-inch, with the emphasis on capturing the songs in one hit. Tracking, therefore, typically involved the delicate dance between pulling various sounds and setting basic levels quickly, constructing several headphone mixes (with each of the player’s names emblazoned on the console’s individual auxiliary sends for quick and risk-free changes to eradicate any guess-work involved) and ironing out any faults, gain structures or ‘underwhelming’ recording chains with a minimum of fuss. To that end, my assistant/second engineer Veit Mehler was a trooper, always sensitive to the fact that I was mainly concerned to keep the lines of communication open, and that as much as possible, engineering changes and repatching needed to take place almost invisibly, something we managed quite well together.

With J often in the control room with a Shure SM57 in front of his acoustic (by J’s special request), I was also regularly monitoring through cans, which I typically do anyway during tracking because above all else it’s crucial to be sensitive to what the players are listening to. I know this is an oft-trotted out cliché, but it really is imperative that the players are quickly made comfortable and not left ‘hanging’ while an engineer has his or her back to everyone and their head in the patchbay. And because albums are also fundamentally about that other clichéd notion, ‘trust’, I much prefer leaving the talkback mic open initially during setup; it forces people to mind their ‘Ps and Qs’ and it negates the unnatural sonic isolation of a studio, which has a tendency to flip people out, particularly if they feel like they’re being ignored.

THE CAPTURE

Most of the basic Whitlams tracking was aimed fairly and squarely at capturing the drums, bass and electric guitar – and acoustic, when it was played. Tim’s vocals and piano were theoretically only guides; the piano initially being played on a Yamaha electric that Tim plays live. The vocals, however, were treated as keepers – as they should almost always be – but I have no memory now if we ended up using any of the guide vocals or not. Suffice it to say, one of my very first priorities was to determine the most likely mic candidate for Tim’s main vocals. Whenever we took a break or stopped for lunch to deliberate over song arrangement or watch the cricket highlights, I swapped the vocal mic, searching for the one that would make Tim’s voice shine. After about five or six changeovers (sometimes trying the same mic twice) we settled on one of the studio’s several vocal masterpieces, a Neumann M49. It was perfect for Tim because it offered superb clarity, with an added bass response to capture his voice in a generous, full-chested way.

Most of the recording chains were actually very simple, and given the number and variety of mics at our disposal (thanks to Electric Avenue’s massive vintage mic collection) very little was tracked with EQ, despite all the magnificent APIs, Neves and Pultecs on hand. This took at least one element out of the chain. If I didn’t love a sound I usually moved and/or changed the mic over until I hit upon the tone I was after. J also does a lot of recording and between us we managed to determine pretty quickly whether a sound was working or not.

Drums were positioned in one of the smaller rooms so that the ambient mics wouldn’t sound too enormous when they were compressed and mixed. Again our ‘production philosophy’ involved closer, tighter sounds during the initial tracking stage. I miked the kit in a fairly orthodox manner: a U47FET on the kick drum (placed outside it, under a rug to improve the isolation and make it ‘tighter’), a ‘bug’ mic taped to the front skin, SM57s on the snare top and bottom (with an Octava 012 taped to the top mic on occasion), Sennheiser MD421s on toms (initially), Neumann KM84s on hi-hat and ride, and Neumann U67s as overheads. I also had a stereo Royer placed in the room (which moved around a bit) and another ribbon was positioned behind Terepai Richmond’s head, facing down into the snare and kick pedal.

A second kit was also set up in Electric Avenue’s large tracking room (a move which J and I had contemplated from the start) so that we could switch drum sounds quickly if the mood took us, or if, as I suspected, there might be times when J or I might get on the second kit and record two sets of drums at once during a take. It also gave us a genuine second option so that a change of heart about our sound wouldn’t involve the session grinding to a halt for four hours. The second kit was smaller and lighter, miked only with a 421 on the kick, a magnificent AKG C24 slung high above the kit and Neumann KM56s (valve pencil condensers) on the snare and floor tom. (The second kit was eventually used for the recording of Second Best).

Guitar setups changed a fair bit during the recording of the album: different amps, different guitars, different rooms, mic and mic placements… although initial tracking involved Jak Housden playing various guitars into his Fender Twin, which had an AKG C12a and an SM57 in front of it in X/Y, with an AEA R84 ribbon some distance back. (Some of this guitar was also performed with J playing my Gretsch Streamliner.) Because I initially had no idea who would be mixing the album, my intention was to give whomever that person turned out to be some options… not hundreds, just a few. The basic guitar setup would allow some tonal adjustment without the need for EQ (courtesy of our X/Y pair), and the ribbon could be added to (or used instead of) the close mics (digitally time-aligned later, if necessary). I also recorded natural reverb for the electric guitar on a couple of occasions after accidentally hearing the amp’d sound echoing down the tiled hallway of the studio. On each of these occasions I waited until the guitar takes had been finalised before feeding the recorded signal back into the amp, turning it up to ‘11’ and sticking a condenser 30 yards away up the hall. Nothing beats a natural reverb – if you have the chance, capture it (and if the reverb’s pre-delay is too long you can always move the file later).

Warwick Hornby’s bass cabinet was (unavoidably) in the same room as the guitar amp so great care was taken to make sure the two were isolated from one another as much as possible. Another U47FET was called into action for bass amp duties and a bass DI channel was recorded as well.

Preamps and compressors, generally speaking, included Neves on all the drums, bass and main vocal channels (via the Melbourn sidecar and racked 1272s), Summit valve pres on the electric guitar, and a Telefunken on the acoustic. Most of the tracking involved minimal compression: an LA-2A was strapped across the vocal, dbx 160s and Distressors on the kick and snare mics, an Al Smart C2 on overheads, Urei 1176s and Neve 2254s on guitars and bass.

Once all the sounds were established and the recording chains largely settled upon, tracking was to the studio’s supreme (and unique in Australia) Ampex ATR124, two-inch machine. This recorder is a real beast with a superb top-end response, rock-hard bottom end and sweet midrange. Combined with the Neve 51 Series console, initial takes coming back off tape sounded great, and very little tweaking was required, mainly just the finessing of gain structures and levels to tape.

Most of the tracking sessions, of which there were many, involved recording several takes of songs to the two-inch machine until everyone was satisfied that we had each song nailed. Some overdubs were then added to the two-inch masters, all of which were then transferred into ProTools for editing and further overdubbing. But like all sessions, and recording philosophies, things don’t always go according to the script…

DUBBING OVER THE OVERDUBBING

Once the tape was shelved and the open-ended doors to the digital domain were flung open, things inevitably got complicated. Although the basic tracking was done and dusted relatively quickly (although at least two or three songs loitered in the wings for months before they were finally recorded), the songs began to stretch out like chewie on a shoe. When people began enquiring about where the project was ‘at’, I found the question difficult to answer. But records are like that most of the time anyway, so it was no big deal… but the chewie was beginning to stretch quite a way!

Some of the overdubbing was recorded at J’s house in Melbourne (and later in Gippsland when he moved to the country). Much of it was played by J himself; electric guitars were miked with AKG 451s, SM57s and a Neumann U87 (which also captured the main vocal on occasion), all driven by a UA6176 preamp. Tim, J and I also sang most of the B/Vs on the record through either a U87, a disparate collection of ribbon mics (to ensure the B/Vs remained ‘subordinate’ to the main vocal) and the occasional SM58, while other parts were recorded in Sydney, with Tim floating between the two cities (as well as London and Byron on occasion). In fact, throughout the projects there were several times when Tim rushed around the studio trying to finish a vocal, tweak that mix or modify a master as if the world was ending later that day, and he was buggered if it was going to happen before the album got finished! On one occasion we were recording a vocal and I was trying hard to get Tim to settle (a difficult task at times!) but he was agitated and just wanted, in his words, to “do six takes of the first verse and get out of here!”.

“Why are you in such a rush, anyway?” I replied. “You can’t just storm into the studio, sing a sensitive part like this, and then storm out again.”

“Bloody oath I can,” he retorted. “You seem to be forgetting something Andy: I’ve got to get on a plane to London in four hours and I still don’t know where my passport is!”

“Okay, we’re rolling then…”

That was the ‘working method’ we employed for many of Tim’s overdubbing sessions.

THE CHEWIE STRETCHES FURTHER

Although there were still some songs yet to be recorded, while others were only half tracked, sometime during last winter the focus temporarily switched to Melbourne and mixing the first group of finished songs. By that stage I’d been handed the job of mixing the album as well, which I did with J and Tim in Sing Sing’s magnificent ‘K Room’. We quickly made ourselves at home in our new place of residence (easy to do at Sing Sing) and got to work. I hadn’t used a K-Series SSL before and I was quite excited to get my hands on the board, as was J. We didn’t exactly get off to a flyer, however, as our first song was still a bit of a mess in terms of the final editing. J had been overdubbing on a ProTools LE system that frustratingly doesn’t allow easy access to an entire ProTools HD file (some of which were 100+ channels), so several hours (or was it more than that?) were spent tidying up fades, re-linking lost files and generally bogged down in the ‘digital doldrums’. But eventually the wind picked up and we were away.

Mixing was a long yet enjoyable process with most songs taking every bit of two days to complete – often broken up by games of table tennis that included playing shots off the side walls to break up the monotony, while Tim watched DVDs of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Several of the mixes involved all 72 channels of the SSL and an unknown number of its small faders as well. We also used ProTools to group automate certain things like backing vocals in order to ‘minimise’ the channels on the board.

There were no particular rules to the process: we used Lexicon 480Ls, TC system 6000s, old AKG springs alongside plug-in reverbs of one sort and other. We used real Fairchilds one minute and ‘digital fairchilds’ the next. We patched in Pultec EQs, the console’s EQ, outboard, on-board and plug-in compression as well as both forms of automation and panning control. The trick to all of this was to manage the two worlds and never let the mass of technology at our fingertips distract us from our aims. All the songs were simultaneously mixed to a half-inch Ampex machine and ProTools; Tim always at me about the ‘point of using tape’ every time a new fresh (and costly) half-inch reel was laced up!

Because J and I were both hands-on during the mixing process, we tended to tag-team a bit; I’d be working on fine tuning the vocal tone while J worked on wild automation passes of his backwards guitar parts. Or I’d mix a song for four hours and then take a break at which time J would step in and continue the process. There were times when we disagreed about how a song should be mixed and occasionally we felt frustrated by one another’s differing vision, but ultimately the process got the mixes over the line, and by and large, mixing at Sing Sing was a real pleasure. As I often remarked to people who came to visit during the several weeks of mixing, “If you can’t mix a record with all this beautiful equipment, you can’t mix a record!”.

On a couple of occasions at Sing Sing we also took over the Neve room down the hall and mixed some songs in there as well. It seemed like a good idea at the time, but ultimately I don’t think it made the process any more efficient. The mixes sounded great, but switching between rooms and acoustic environments was a difficult challenge mentally – it often made J and I overreact to mixes when we first entered a room.

We also decided to do some overdubbing while we were there (mainly of vocals), which took place in Sing Sing’s G+ SSL room. Pretty soon we’d taken over the whole facility – which Tim has quite a penchant for. He likes the feeling of every room in a facility working to a single purpose.

WINTER, & NOTHING BUT THE BOOZE?

By the time the first mixing session at Sing Sing was over things started to feel a little disorganised. There were two-inch masters sitting on the shelf at Electric Avenue, song files on three in-house computers at Sing Sing, digital backup on three external drives labelled ‘Tim’, ‘Andy’ and ‘J’, which went with us from session to session. There were half-inch masters, 24-bit/96k masters, 24-bit/44.1k masters, LE and HD ProTools files (some of which had overdubs on them from J’s home studio sessions, some of which didn’t). There were clandestine sessions with Tim re-recording vocals with Veit in Sydney, overdubbing sessions during mixdown in the K Room, rough mixes, sub mixes… in fact, there were so many sessions that pretty soon I was too scared to contemplate erasing anything from the drive labelled ‘Andy’ for fear of losing that crucial ‘olive branch’ overdub that was recorded onto track 105!

What all this tracking and re-tracking, overdubbing on the overdubbing, mixing and remixing was mainly about was working methods and expectation. Tim was the driving force behind most of it, naturally enough: revisiting his piano and vocal performances on several occasions as the songs evolved in his head (and on the road). Tim’s a hard worker, and he would often stand in front of the mic or sit at the piano for hours at a time without a single complaint (well, not many anyway… ). A perfectionist or an obsessive (depending on your viewpoint) Tim was never satisfied, always striving for something better and always giving it his all. Some of this striving for perfection was frustrating at times, particularly when it involved re-doing parts on songs that had already been mixed! But in the end, it was Tim who needed to be satisfied by the final masters. It was his head on the block after all. In all honesty, I have never seen a work ethic like it. None of the red wine drunkenness that I had been forewarned about ever eventuated and it actually became a running joke between Tim, J and I what a boring, sober bunch we’d all become. Tim adding: “It’s the first record I’ve made sobre but I hope it doesn’t sound like it!”

TAG & RELEASE

Producing a record is not like working for a bureaucracy or building a house… as most readers of AT know all too well. There is no ‘definitive process’, no ‘right way’ or script, only ‘guidelines,’ and ‘gut instinct’.

At the start of the project I had no idea what really lay in store for us. I hoped the recording process would run smoothly and harmoniously, and generally it did. What it mainly reaffirmed, however, was that flexibility and the maturity to resist rushing to judgement are crucial to any drawn out musical enterprise that involves so many characters and personalities. Tim was determined to make the most of the time he had to remix songs, master and re-master the two discs that make up the release (which is due to come out some time in late February). Much of that time involved what, to outsiders, seemed like second-guessing and meddling, but what it was actually about was a striving for perfection to make sure the release was as good as it could be. Although this made the project longer and more difficult, (Rick O’Neil claims to have made as many as nine different sets of masters!) it was refreshing to be involved in a project that aimed so high and expected so much.

As I flew down to Melbourne on Christmas morning, hoping the airport shops were open so I could buy my family some presents, the project was finally over, and Tim’s focus was shifting to issues concerning artwork and film-clips. It was finally ‘in the can’ (something I’d naively thought several times before) so this time I whispered it to myself so no one could hear. It was an extraordinary experience for us all, musically, mentally and technically, but it was well and truly worth it.

RESPONSES