That Human Touch

Electronic act PVT move from cult label Warp and head to a country manner to inject their new record Homosapien with a breath of fresh air.

PVT’s writing process is a finely-honed intercontinental square dance between London and Sydney, where files are swapped between band members like partners on a dance floor. The electronic band is made up of frontman Richard Pike (living in London), his brother Laurence and Dave Miller (both in Sydney). PVT recently left cult electronic label Warp Records, home of Aphex Twin, for Create Control to release their latest record Homosapien.

Music can be a rough cycle. After sweating over an album, it’s not just a matter of washing off, rinsing and repeating. It’s straight into the tumble drier of a tour — a similar machine, just hotter, and prone to meltdowns.

The cycle usually ends in post-tour blues. Exhausted, summoning up the effort to go round again can be tough. The force required to drag each other out of the post-tour blues helped shape Homosapien, it was like starting all over again. “We took a little break, a deep breath and tried something different again,” said Richard. “The record felt really fresh in that regard.”

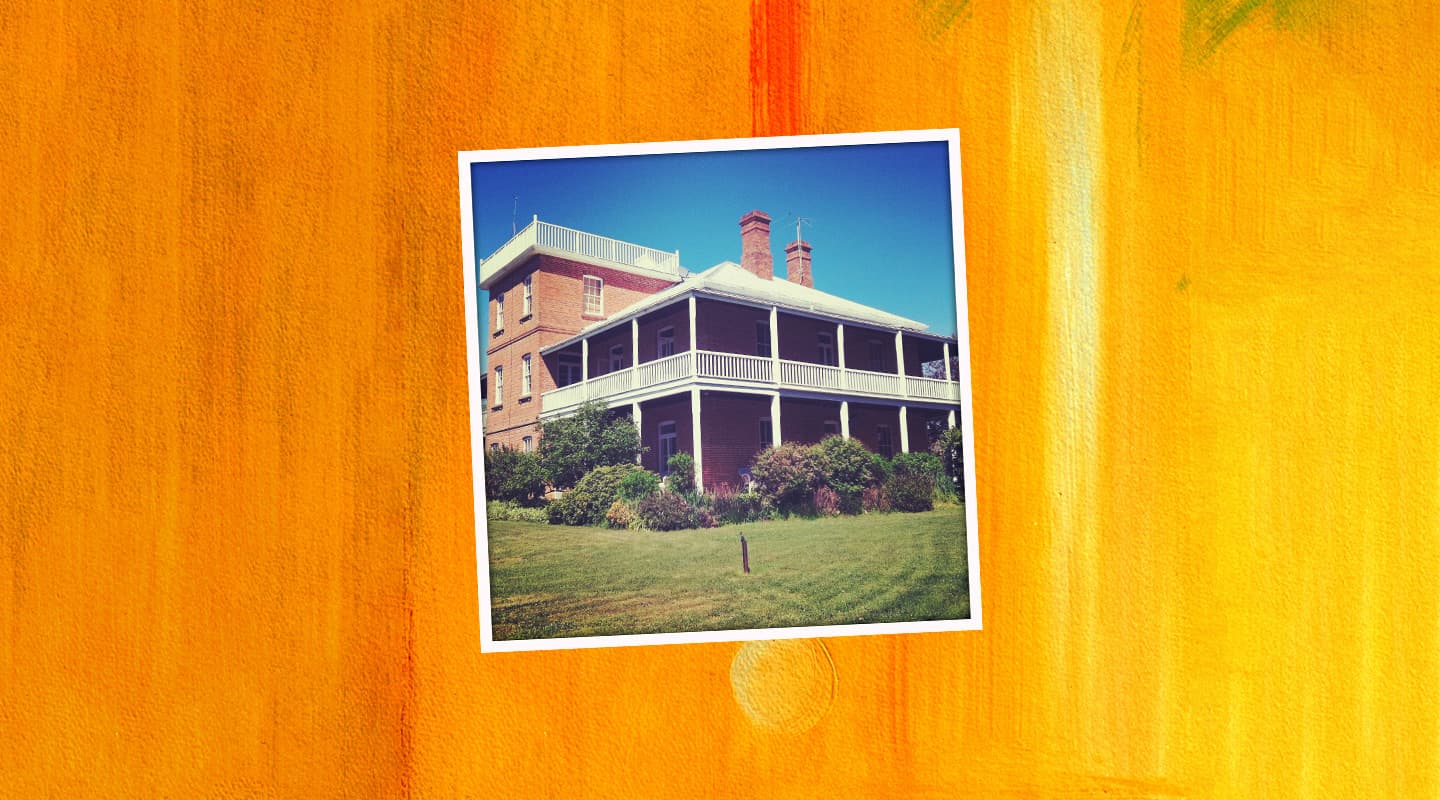

A little break, deep breaths, and fresh air were exactly what PVT found in a country manor in Yass, a small town just north of Canberra. It’s a place not unfamiliar to Australian bands. Both Jack Ladder and The Drones’ Gareth Liddiard have recorded there before, the common link being producer Burke Reid, who had worked on PVT’s previous record. Even DZ Deathrays (a band Richard is producing an album for) are writing at the mansion. It’s buzzing by Yass standards.

“We liked the idea of getting out of the city,” said Richard. “We’ve always done concentrated recording sessions that are on the clock in nice studios with nice gear. It’s a good process if you’re on a budget. But this time we wanted to do the Rolling Stones thing. Go away to a mansion in the countryside and turn it into a record. It was exciting for us to discover a new way to make a record.”

PVT hired Gareth Liddiard’s mobile recording setup for the sessions (whose latest album serendipitously happens to be the feature of another piece in this issue, check it out for more info on his gear). “It’s funny, his town is like where the Sims Brothers live in Chris Lilley’s We Can Be Heroes — one main drag and two pubs. We met him there in his ute looking like some kind of modern Henry Lawson and then we drove the gear back up to Yass — that was a cool process in itself.”

LEADING WITH VOCALS

One of the main differences between Homosapien and PVT’s previous albums is this is the first time Richard has truly embraced the lead vocal role start to finish. “It was organic,” said Richard. “We started doing it live more and more. Dave was taking live samples of my voice, pitching things and doing dubby delays with it. It seemed like the right time to sing again. We feel more mature as songwriters.”

Relying on vocals to lead the way meant another change to PVT’s songwriting regime. Taking 2010’s Church With No Magic as an example, the songwriting process was primarily studio based, where the band would come in with vague ideas and loops, then jam on them in a Can/Krautrock cut-up method. The obvious problem to the approach is trawling through countless hours of material trying to find 10 songs worth of gold. “It becomes a lot of post work,” said Richard. “And it mainly ends up as my job. So this time we wanted to have about 20 solid-ish ideas to choose from. And a record came out of that.”

DOWN TO BUSINESS

To go with this fresh start, and the new vocal approach, the aim at Yass was to get as much recorded live as possible in three weeks. “We didn’t want to spend too much time bogged down in electronics,” said Richard. Which seems odd for an electronic band. “We wanted to get as much live stuff as we could. We brought all the synths we could. We put together a little workshop upstairs so we could work on any keyboard stuff while the drums were being tracked in the main room. We were also in quite beautiful bushland, so if you weren’t tracking you could go for a walk. It was a perfect scenario in a lot of ways. That feeling was nice to be around, rather than having to worry about where you’d park your car every morning when you’d go to the studio in Surry Hills.”

Each morning, everyone would congregate for a meeting and go over the plan for the day. A bit business-like for a creative enterprise, but an organisational necessity that kept the self-production on task. The danger of whittling away the days without getting anything done was one they were keen to avoid.

“We didn’t want to walk away and go, ‘You know what, we really should have… or, this song isn’t cutting it,’” said Richard. “When you’re in that situation you’re isolated and every day you’re getting up and doing the same thing, there’s a concern that you’ll lose focus. It becomes like Groundhog Day. It was important to us to keep a routine and then smash it out and walk away with all the material we wanted.

“I’m of the belief these days that less is more. When we were younger we’d layer the hell out of everything, but these days we’re more impressed with ourselves if we can make a song sound fantastic with less tracks, and make every track count.”

Cutting down on tracks is one thing, but it also means you have to cut the crap. “A lot of it is saying no to bad sounds!” said Richard. “It’s a mistake a lot of young producers make. They think it sounds good just because they programmed it, when really they should be replacing it with another sound. Having said that, sometimes we’ll use a sound that’s not necessarily sonically rich, but you still like the sound because it has a certain grit, air or weirdness that you can’t fake. It’s a constant experimentation and your ears are your best friend in that situation — you’ve got to be discerning.”

These days we’re more impressed with ourselves if we can make a song sound fantastic with less tracks, and make every track count

METHOD OF EVOLUTION

Richard gives an example of this newfound approach with one of the simpler tracks on Homosapien called Evolution.

Richard: “Essentially I made an arpeggiated MIDI track using the Arpeggiator plug-in in Ableton Live and sent that out to the Juno 106. It’s the reason I still love the Juno. It’s digital [with an analogue filter] but it sounds analogue and you can use MIDI, you can play it live if you want, and you can mutilate it on the spot. It’s not too difficult to use.

“So it started with the arpeggiated brass synth sound that I tracked a Roland TR-606 drum machine along to. I didn’t sync up the 606, I just played it in and used the warp function in Ableton to drop it in time. The synth pads were done on the Arturia ARP 2600 soft synth, fiddling with the filter. That was the basics of the electronics on that — dead simple.

“Then it’s just about getting the nuances right, being really specific about where we want it to ebb and flow, where we want the filter to come out, and when we want the notes to be short or long. Those things are what makes the arpeggiator really organic and expressive.”

It sounds like PVT have grown up — moving to the country, taking a ‘less is more’ approach. They’re an electronic band that’s maturing with age, slowly adding more of that human touch.

RESPONSES