Playing in the Wet

Steven Schram was getting so carried away mixing Darren Middleton’s new album, he didn’t realise he was sitting in an inch of water.

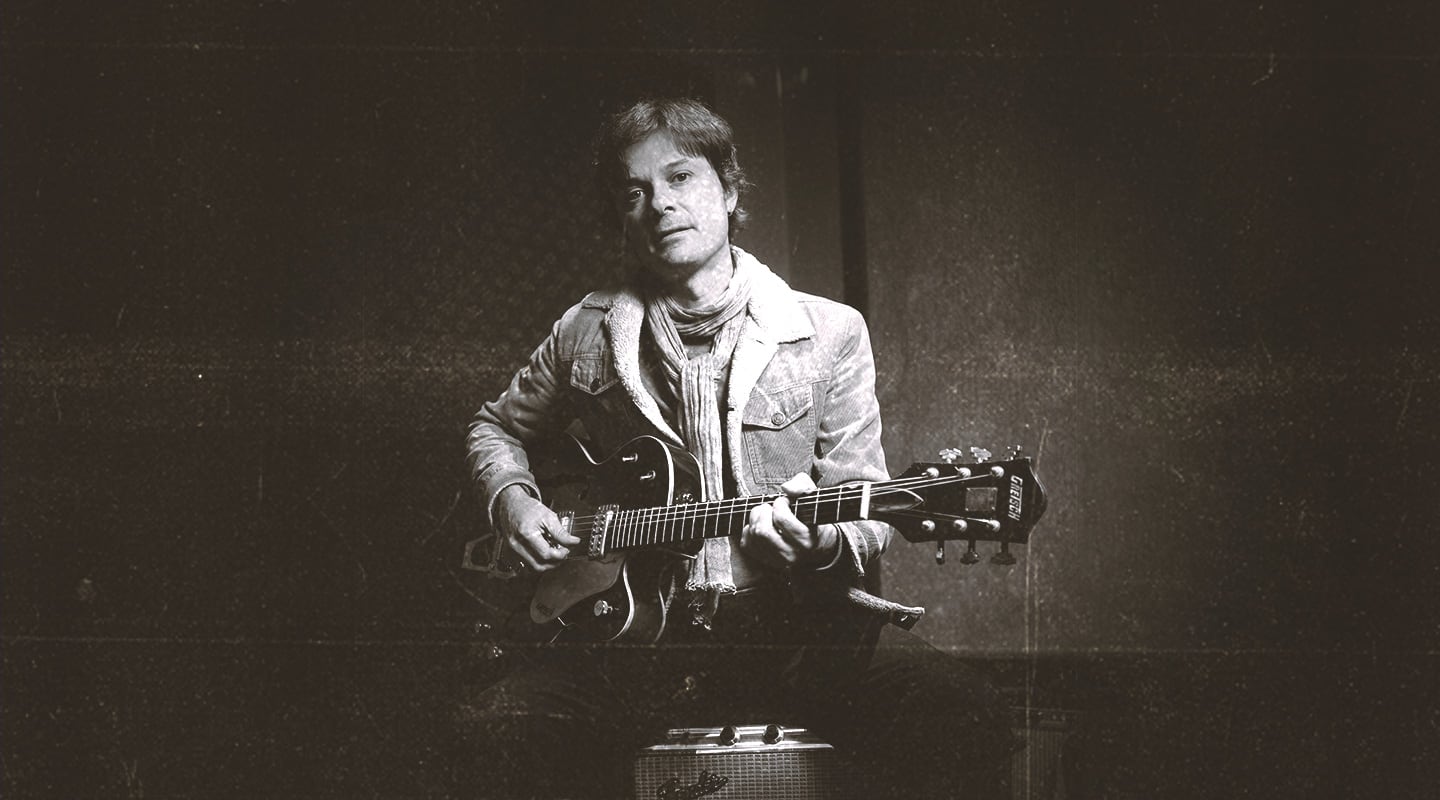

Artist: Darren Middleton

Album: Tides

Steven Schram was two hours into a mix that was coming together swimmingly when he found himself in deep water. “Things were really cooking, then I heard a squishy sound. I looked behind the screen and there was an inch of water coming through the studio wall. I was thinking, ‘I can still finish this mix. Just 10 more minutes!’ When the power board started to lift off the floor, I figured it was time to get out.”

The top of the hot water service had blown off, but with the screen in his way, he’d been sitting there mixing not realising he was slowly sinking. He quickly shut down the studio and turfed all his gear out the door, managing to save everything except the acoustic treatment and rugs.

Fittingly, the record he’d been so wrapped up in that he almost floated away was Darren Middleton’s new album… called Tides.

KEEPING THE POWDER DRY

Things were a lot drier at Middleton’s studio in Melbourne. His single-room studio is a guitar haven, as you’d expect from the ex-Powderfinger guitarist. He’s got a selection of esoteric gear and pragmatic devices — from the vintage Roland GR-500 guitar synth and accompanying GS-500 guitar controller, to his diminutive board of Chase Bliss digitally-controlled, analogue pedals — but it’s all functional, and all used.

His studio is nestled at the back of the Revolver building. On the ground floor, thankfully, escaping Revolver’s dreaded stair load in. He’s been in this location for a few years now, having taken over the lease when Something For Kate’s Paul Dempsey moved his studio back home. Amps and guitars stretch out down one wall, and there’s enough room to set up a drum kit when he needs to bash out some demos.

Though he’s just on the cusp of releasing Tides, which is what I’m there to talk about, he’s also working on the soundtrack for a local independent film. He keeps a pretty full calendar these days, but it looks a lot different from the long album cycle blocks of his Powderfinger days. “That’s the thing with being in a big, successful band,” recalled Darren. “Obviously, it’s amazing, but because there are so many big things involved — big record companies, long timelines — everything moves very slowly.”

He’s always been a prolific songwriter, but couldn’t open the shutters during those Powderfinger cycles. Occasionally they’d take a break so they could flex their muscles — Darren did an EP and album with his side project, Drag — but these days he sees it less like blocks of time, and more like one long road where there are no side projects, and solo albums are interspersed with film scores. “Keeping busy and practising your craft, you learn different ways of doing things, you also meet people and form different relationships and partnerships,” he explained, plus “I’m not really the kind of artist who’s content with privately making music in my bedroom. I actually want people to hear it.”

CHANGING TIDES

For Tides, Middleton’s main ambition was to capture more grit and energy, “because my other records are more neat and tidy.” He asked good friend, musician and producer Davey Lane (You Am I) to help him pull the pieces together. Lane helped with pre-production, then assembled a rhythm section, which included drummer Graeme Pogson from The Bamboos, and bassist Luke Hodgson (Megan Washington). Both were unknown to Middleton before the sessions, but he trusted Lane’s judgement, and thought that level of unknown would add to the vibe. “If I was morally opposed to one of them or if I just hated them, I’d cancel it straight away,” disclaimed Middleton. “But we got on, and I really want people’s character. I don’t want to tell people what to play, I give guidelines and ideas, then choose what I like at the end. Music is about people. It’s the story of our lives. I certainly want them to impart a sense of who they are onto that instrument.”

He’d never met string arranger Xani Kolac either, but she also nailed the brief.

With all the songs demoed up in his own studio, they went to Head Gap studios in two different blocks to lay down live beds. Although he wasn’t there for the tracking, Schram was happy about that choice at his end: “Anything that comes out of Head Gap is really malleable. They give you so many options that are all usable. I can grab just one mic and get the whole drum sound out of that. They also have the close mics aligned with the closer overheads, then they’ll have another combination of mics that seem to fit well together. That’s been consistent the whole time, just constant quality — a great-sounding room and they treat it professionally. If they’re not mixing it, they don’t paint anybody into a corner.”

SUBMERGED IN GUITAR HEAVEN

After the main beds were down, Middleton retired to his studio to overdub the guitars and vocals. “The philosophy was lets work out what we’re doing, record it a few times and just pick a take that feels the best,” said Middleton. “If it wavers a bit, that’s fine. I still carried that philosophy back here. I worked out roughly what I wanted to do then recorded a few times. There’s no copying and pasting, and as much as possible, it’s a whole take.”

Middleton’s recording ethos likewise limits the amount of meddling: “Put a good signal into a good mic and it should be a f**king good result if you’re playing well.” He’s definitely got the guitar sounds nailed. Middleton talked us through how he recorded the second song on the album, In Record Time, which drops down from the big beat, wall-of-sound opener to a more intricately-arranged, tight-sounding track.

While other songs are more straight out, ‘Vox in one ear, Fender in the other’ rock tunes, there’s less guitar on In Record Time, but it’s more specifically arranged. The main verse guitar is Middleton vamping along on his Diamond Anniversary Gretsch. “On top of that, there’s a counter guitar,” said Middleton, demonstrating a technique where you flick the whammy as you play to create a flutter sound. Another sound he makes is with a Boss Tera Echo pedal. “It’s not that popular, but it’s very good,” said Middleton. “It’s kind of a delay/reverb in one pedal. I’ll run it a lot, because it just floats around and makes it sound a bit Brit Pop-py, but when you strike it really hard it sounds like phaser-y delay repeats.”

On the solo, he broke out his Roland guitar synth. It’s a huge floor-bound synth linked to a controller guitar with all manner of knobs and switches. “I pulled it out of storage for this record, and used it a few times because it’s a secret weapon. The module has three sections; a bass section, a poly ensemble and a solo/melody. You can switch them on and off as well as blend the volumes of each section to create the sound. It’s got infinite sustain, too. It sounds like a guitar, but a bit special.”

His go-to guitar mic is a Royer R-121 ribbon mic sat half a foot away from the cone and occasionally accompanied by a Shure SM57 or ’50s Neumann CMV-551 condenser with an M7 capsule, which he also used a lot to mic his Gibson J-45 acoustic.

I heard a squishy sound. I looked behind the screen and there was an inch of water coming through the studio wall

LINKING UP SECTIONS

On the way in, he uses his pair of Aurora Audio GTQ-2 Neve-style preamps built by Neve alumni, Geoff Tanner. “They’re really good and reliable, unlike half of the old school Neve stuff.” In his rack he’s also got a collection of outboard reverb and delay units, including a Real D spring reverb he uses a lot. “Whenever I would use any analogue effects, I would do it live and record the dry signal alongside the effected signal. I double tracked the solo and sent the left side into the Space Echo with a certain delay speed, then sent the other side into it with a different delay time to create movement, then bounced it all back in. I also grabbed little bits of the delay and reversed them.”

At the end of the chain, Middleton uses an iZ RADAR system. “It’s about 12 years old, and it’s just a multi-track recorder. It was the first one the pros were using around the transition from tape to digital, because it sounds amazing. The drums and bass and guide guitar went via tape, and everything else went through that to maintain that level of quality. Nick Didia still hassles me to buy it, but I’m not letting go of it.”

It all goes into Presonus’ Studio One DAW because “Pro Tools expired and I didn’t bother renewing it. I got onto Studio One a year and a half ago and much prefer it. I find it really accurate, easy to use, and as complicated as it needs to be.”

LIFTING THE ARIA CURSE

Back at Schram’s place, he’s dry and hearing his Kii Three cardioid monitor speakers better than ever courtesy of some new acoustic treatment from Chris Fatouros at Exponential Acoustics (see box item). It doesn’t mean he’s settled though, after our conversation he’s due to pack up the last bits of his studio and ship them off to Byron. He’ll be living near and working out of the newly revamped Rocking Horse Studios, which we covered in Issue 129. “I’ve been working out of there quite a bit with a band called Wharves and it’s been fun,” he said. “I like the Workshop a lot.”

Everything’s been really humming along since the ARIA curse lifted, said Schram. Hold on… ARIA curse? “You don’t want to win those f**kin’ things, they’re the kiss of death,” he said of his Engineer of the Year ARIA for Paul Kelly’s Life Is Fine. “You don’t work for a year after you get it.” He’s not sure exactly why that is — whether people think you’re too expensive now — but he’s sure it’s a real curse. “There was nothing in my calendar, then all of sudden it was booked until March. I thought, ‘maybe the curse has lifted.’ Sure enough, that morning they’d announced all the new nominations.

“Chris Thompson, another ARIA winner, rang me two hours later to say, ‘congratulations on getting nowhere near the nominations this year.’ It’s legit, you don’t want those pointy things. They’re a poisoned chalice. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. Now Burke [Reid]’s got one, he can be miserable for a year until the curse moves onto somebody else.”

LOOSE LEASH

Schram hadn’t mixed any of Middleton’s or Powderfinger’s records before, except a “live recording from a tour in Sydney once, but not major releases. Not guilty… wasn’t me.” But Middleton knew all about Schram’s tendency to completely shake mixes up, and was happy to let him run with that. “I gave him free will,” he said. “I wanted his character in there, which is what he does. When he sent the mixes back, I was like, ‘holy s**t!’ I was genuinely pumped.”

“I felt I was off the leash and could push things as hard as I felt necessary,” said Schram, who prefers “to push it a little too far, then rein it in, rather than getting halfway to something.” Adam Ayan from Gateway Mastering actually sent back a “mini essay pointing out a buzz here, a clip there, and something else was too bright, and you’re hitting this too hard. Adam’s great, he lets me know if I’ve missed things, though not too often, which is nice.”

THE MIX FOR IN RECORD TIME

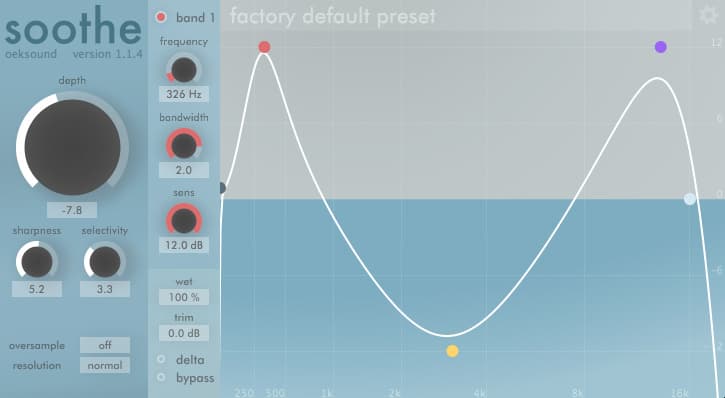

RESPONSES