Elvis: Orchestrating The King’s Recoronation

Elvis doesn’t need orchestral backing, but Priscilla Presley reckons it would have been a ‘dream come true’ for The King. AT talked to the team that made that dream a reality by using the best of old and new technology to draw two worlds together.

On first hearing it, the concept of releasing an album of original Elvis recordings with new orchestra overdubs seems a dreadful idea. The legacies of quite a few great musicians who’ve kicked the bucket have been soiled by ill-judged albums of material reworked after their passing. Witness much-derided releases like Hendrix’s Crash Landing, Jeff Buckley’s Songs To No-One 1991-92, and Michael Jackson’s Michael. Accusations of skulduggery and grave-robbery are always a risk with posthumous releases, and defacing some of The King’s greatest recordings with schmaltzy Hollywood strings seems an obvious act of gluttonous desecration.

However, as we all know but keep forgetting, first impressions can be deceptive. Even on first listen, it’s clear If I Can Dream — credited to ‘Elvis Presley with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’ — sounds downright spectacular. The opener, the up-tempo Burning Love, starts with the orchestra in mono, then pans out to stereo, like a period movie starting in black and white and then fading into full-colour, and continues to rock along for another three minutes, with a remarkably in-your-face and tight-sounding orchestra playing perfectly in time with the band. Nothing syrupy about these strings. The band and orchestra wonderfully complement Elvis’s vocal, which sounds as if it was recorded yesterday, not in 1972.

The rest of the album contains similar high-points, including classic tracks like Love Me Tender (1956), Fever (1960), and Bridge Over Troubled Water (1976), with old and new ingredients seamlessly blended in larger-than-life panoramas. If there is dissonance, it’s that some of the orchestral arrangements are overblown (You Lost That Loving Feeling) while some of the songs are, to modern ears at least, dated and/or of dubious quality. The melody of It’s Now Or Never, for example, has the effect on this writer of the proverbial fingernails scratching the blackboard. But obviously, the makers of If I Can Dream can hardly be blamed for this.

THE DREAM A REALITY

So what happened? How did an artistically and morally dubious idea turn into an artistic triumph, as well as a commercial success? Elvis’s 80th birthday present sold more than a million copies in the UK, and has gone platinum in Australia. It turns out these feats are not only due to the apparent good taste and great technical skills of the makers, but also to the fact that some of those involved had direct links to Elvis.

The participation and public endorsement of Elvis’s ex-wife Priscilla Presley, who executive produced If I Can Dream and called it “a dream come true for Elvis,” has been widely covered. But the very first seeds for the project were planted by Don Reedman, an Australian producer and composer who moved to the UK in 1969, and soon afterwards found himself working for Carlin Music, the publishing company of the legendary Freddy Bienstock. At the time every song pitched to Elvis had to go through Bienstock, and Reedman was amongst those at the company tasked with finding Elvis songs. One of the songs he unearthed was Clive Westlake’s It’s A Matter Of Time, which was released in 1972 as a double A-side single with Burning Love.

“I never got to know Elvis personally,” recalled Reedman, “but I knew many of the people around him. I was part of finding songs for Elvis to sing, demoing them in the way we thought he wanted to record them. Elvis picked the ones he liked, and usually went along with the direction of the demos, but when we got the final recordings back, it always really hit us: this is Elvis Presley! He just had a phenomenal voice. However, I often felt many of his songs were underproduced, largely because of budgetary restraints, and could do with much bigger accompaniments and orchestrations.

“Elvis’s phenomenal voice always stayed with me, and I long wanted to give something back to it in terms of record production. Retain the spirit and feel of the original recordings, but build on that by putting a full symphony orchestra behind him on the right songs. My vision was to create a new, fresh Elvis album, that would showcase Elvis’s amazing vocal scope; from rock ‘n roll, to gospel, to rhythm ’n’ blues, to operatic ballads, and so on. It took a long time for me to convince people to do this. Thanks to the latest development in digital audio technology, and the amazing knowledge of the people we worked with, I think we managed to make a much better record than could have been made even five years ago.”

FROM 3-TRACK TO NOW

Reedman’s co-producer was Nick Patrick, a British Grammy Award-winning engineer, mixer, arranger and producer, who started out working with world music acts in the 1980s, but who has increasingly become involved in classical music crossover projects this century. From his Shine Studios in South-West England, he explained, “The whole thing started as a symphonic album project. That has different connotations for different people, but for us it was always clear that it wasn’t just going to be an orchestral backing with Elvis’s voice on top. We couldn’t just do a wholesale remake and replace the existing backing tracks. That would draw the soul of out him. We knew we had to reimagine the original backing tracks to retain the spirit of what made him sound great.

“Once we received the original multi-tracks from Sony, transferred flat into Pro Tools sessions, it became clearer what exactly it was about the backing tracks that made Elvis sound so good. We likened what we aimed to do to restoring the Sistine Chapel. We would have to strip away parts only to rebuild them using the same materials made in our time. As this idea unfolded in practice, it became a bigger and bigger task. One issue was we had material dating from 1956 to 1972, ranging from three-track to 16-track. That shift in technology had an enormous impact on the way records sounded.

“Also, none of the songs had been recorded to click track, and the changes in tempo could occasionally be quite extreme. Elvis was also always in the room with the musicians, so there was a lot of spill and many of his vocals were recorded with reverb all over them. For all those reasons we had to embrace what was there, and the challenge of seamlessly mixing the old with the new kept growing. We really didn’t want it to sound like a 1968 recording patched together with a 2014 orchestra. The connection to the original music, and the way it coexisted with the new recordings was absolutely crucial to the artistic success of the project. It became a very emotional project, and an enormous technically forensic project.”

On Burning Love she did 400 tiny edits on the new drums alone to make them fit exactly with the original drum track!

HITTING THE BEATLES’ STUDIO

Reedman and Patrick’s first step was to take stock of the Pro Tools sessions with the original Elvis recordings, edit them, strip them of what they didn’t need, create tempo maps, sometimes altering the structure to make space for the orchestral arrangement, and then commission orchestral arrangements from the likes of Nick Ingman, Robin Smith, and Steve Sidwell. The two producers also began adding new material, like drums, bass, guitars, keyboards, and backing vocals, recorded by Pete Schwier. The next call they made was to Peter Cobbin, another Australian, who moved to the UK in 1995 and — as Abbey Road Studio’s Director of Engineering — has worked on scores of household-name orchestral, film score, and pop projects, and won two Grammies for his contributions to the Lord Of The Rings soundtrack albums.

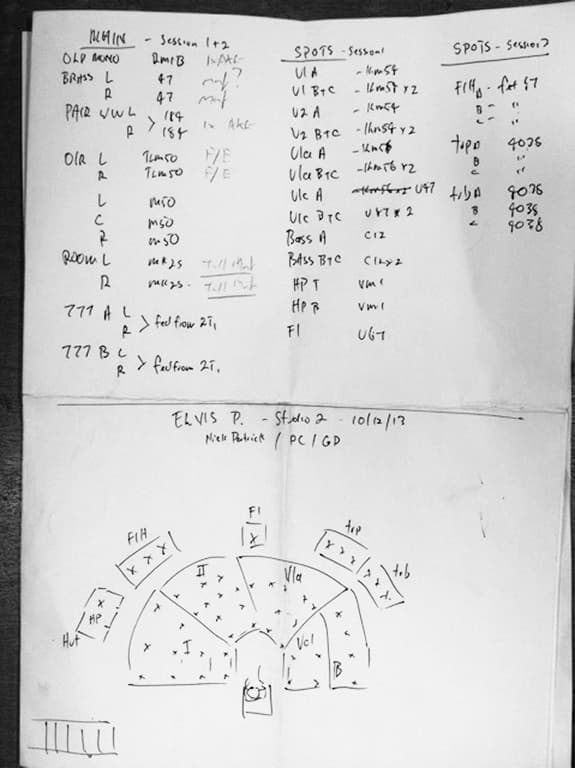

Cobbin agreed to get involved, and booked the first orchestral recording session on December 10, 2013 to record strings on four songs: Bridge Over Troubled Water, Love Me Tender, You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling, and Burning Love. Unusually, but explaining a lot about the direct and tight orchestral sound, the session took place in the smaller Abbey Road Studio 2, also known as The Beatles’ studio, and not in Studio 1, Abbey Road’s normal venue for orchestral sessions. It was not the only unusual thing about the orchestral sessions for the Elvis project.

“I called Don a few times to ask what they wanted and whether they wanted the orchestra to sound modern or not,” remembered Cobbin. “I suggested the idea of creating a sound that’s nice and full, but also authentic to the period of the tunes they were working on. Don and Nick liked that idea. I decided to record in Studio 2, which gives a dryer, warmer, more intimate sound than the full-blown large symphonic sound of Studio 1.

“I also decided to record the orchestra with period microphones, mostly valve condensers and ribbons [such as Neumann M47, M50, KM54, KM56, U67, AKG C12, STC Coles 4038, and more], including an old and very rare ribbon mic; the EMI RM-1B, made by Alan Blumlein in the 1930s. I used the latter for the beginning of Burning Love. I then added a little bit of a convolution reverb of Studio 1 made with the Sony DRE-S777. This allowed me to control the amount of bloom added to the orchestra. I recorded the orchestra to a click taken from Nick’s tempo map and in separate orchestral sections, partly because Studio 2 is a smaller room and partly because we wanted to have separation between the strings and the brass.

“Creating an orchestra sound that wasn’t unnaturally big and sounded appropriate for Elvis’s voice was the first step. At this stage I was getting more details of the kind of album Don and Nick were envisioning, and realised they were also adding drums and bass and other instrumentation. Because of my experience working on the Beatles’ Anthology and Yellow Submarine Songtrack albums, and with Yoko Ono on some of John Lennon’s catalogue, I suggested we go deeper into restoring, renovating, and editing Elvis’s voice and the original backing tracks. That’s when I offered to get Kirsty involved, who is an expert in these things.”

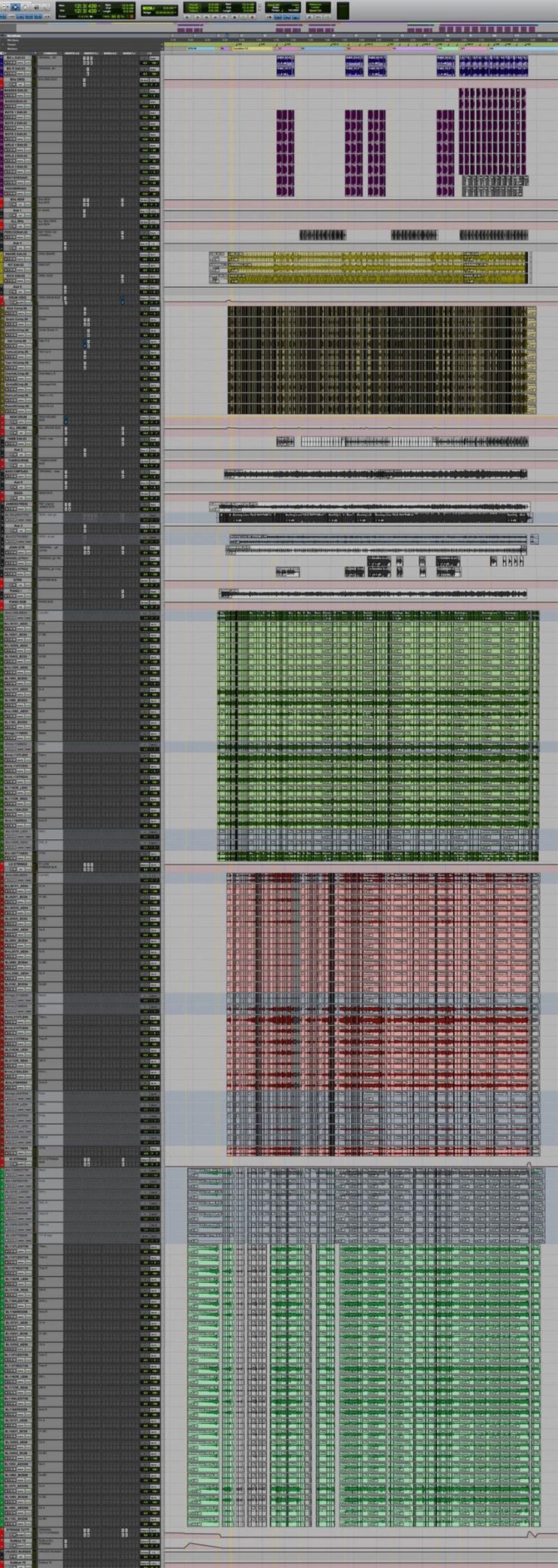

BURNING LOVE SCREEN SHOTS

Comments by Kirsty Whalley

- The (blue) original tracks are arranged at the top of the session, along with the Abbey Road Studio 2 monitor mix and an old original mix. The original tracks are also scattered through the rest of the session where they are being used as part of the main mix. The blue tracks here are not part of the mix but monitored as a separate external source.

- The original backing vocals, new backing vocals, backing vocals combined, and original drums in green/yellow. You can see the new drum comps with tons of edits.

- All the new heavily-edited drum comps in brown-green, plus the drum bus tracks, tambourine, and original guitars

- Original piano, orchestra tracks in green, this is orchestra pass one; low strings.

- In red is the orchestra pass two; high strings. As this was a very rhythmic track they were recorded separately to allow for more flexibility when editing for tightness.

- This is an additional orchestral pass with high and low strings playing together, used as an additional sweetener to the other orchestral passes.

MATCHING TEMPO WITH TIMELESSNESS

Kirsty Whalley — a Guildford University Tonmeister graduate who now works as a freelance editor, engineer and mixer and has collaborated extensively with Cobbin — began work on the original Elvis recordings in her suite at Abbey Road. “I did some research and laid the Pro Tools sessions out in such a way that we could instantly listen to all the original tracks and mixes and reference them,” she noted. “It made it easier for us to make decisions on what to use and not use. I also did a lot of audio restoration work. The sessions were of variable quality, not only because they came from such a wide time period, but also because some of the tracks had been recorded live.

“I removed a lot of tape hiss using iZotope’s RX Denoiser plug-in, and I tried to tidy up as much of the spill as I could. I spent the most time on the lead and backing vocals, because they would be in front of the final mixes and needed to be really clean. There was quite a lot of spectral repair to do on pops and clicks using RX, and dropouts and level drops I needed to correct. I also did a tiny bit of overall tuning adjustment, but the lead vocal was really in tune with a wonderful feel. The songs that needed the most attention were the ballads, like Love Me Tender, and Can’t Help But Falling In Love, because the lead vocal in them is very exposed. In some cases I used Zynaptic Unveil to dry up the mono reverb on the lead vocals so we could replace the reverb with a similar plate reverb, but in stereo.”

Cobbin added that Whalley and he also used an SPL Transient Designer and the old hardware Behringer Denoiser SNR2000 during the restoration process, finding they “could never use one tool for even a whole section of a song. There was no one preset or technique that would always work; we could use one tool for one line then had to use another for the next line. We were trying to restore Elvis’s voice to the most pristine condition we could and use effects they would have used at the time. However much work that was, the editing was even more challenging because of the natural fluctuations in tempo and accents from people playing 40 years ago.

“We tried using only the original drums, but they weren’t wide and large enough to match the big orchestral sound. We tried using just the new drums, but they didn’t always fit with the sound and feel of the vocals in quite the same way. We tried using new and old drums together, but of course, the new drums didn’t quite match the groove and feel of something played 40-50 years ago. Eventually we decided to edit the new stereo drum kit to fit the old one, to get a really good groove and feel with space and warmth to the sound. It became the blueprint of how we did all the rhythm tracks, but making it fit wasn’t easy. On Burning Love, for example, she did 400 tiny edits on the new drums alone to make them fit exactly with the original drum track! We did the same editing process with many other instruments and the backing vocals.

“There was a lovely ebb and flow to the rhythm sections Elvis had, so where possible we gave preference to the original feel, but sometimes — for timing reasons or to fit a new arrangement — we worked the other way around. Sometimes we’d have to edit the orchestra and/or other new recordings to fit what we already had. It was a process of going round the houses, one way or the other, to work out what sounded best. The editing process was often two steps forward and one step back. We’d initially recorded a different arrangement of Fever, then after Michael Bublé was confirmed to sing on it, we changed the arrangement to suit his voice and the key he likes to sing in.”

The connection to the original music, and the way it coexisted with the new recordings was absolutely crucial. It became a very emotional project, and an enormous technically forensic project

HEARING THINGS ANEW

According to Cobbin and Whalley, they took the restoration and editing process further than had been foreseen, and Cobbin also did some final mixes at The Penthouse mix suite at Abbey Road, to present what they had done in the best light possible. Patrick and Reedman, delighted by the results, in turn presented the results to Priscilla Presley and Sony, “who could not believe what they were hearing.” The rest of the album continued on the same basis. Patrick, Reedman, and Schwier recorded more overdubs at RAK Studios, The Bunker in London, and Patrick’s Shine Studios. Then there was a second orchestral session in April 2014, followed by further editing and mixing sessions conducted by Whalley and Cobbin at Abbey Road over the summer. After all that, there was even more recording and another two month mix period at Shine with Patrick, Reedman and Schwier.

One of the final hurdles was determining how modern the album should sound. Cobbin: “Kirsty’s studio — then at Abbey Road — was state of the art, with similar gear as The Penthouse. It gave us a great sense of compatibility, and meant I didn’t need to keep printing mix bounces. We could simply send our work to each other using the studio’s network. I was going through the room’s Neve DFC Gemini desk, but had an analogue mix bus chain with a Manley Variable Mu limiter/compressor, Chandler EMI TG12345 Curve Bender EQ (which I helped design), and a Massenburg 8200 EQ. These days we listen to things in more detail, brighter and with more compression. When we mixed through this mastering chain sometimes all sorts of unwanted noises we’d never heard came to the fore again. Kirsty had to do more cleanup work, and I had to adjust my mix. It was akin with the process of making the album, which was a constant working and reworking.

“The whole recording and editing process took a long time,” added Patrick. “We just kept chipping away at it until it fell into place. We mixed about five tracks at The Penthouse with Peter Cobbin, but that studio was too expensive for us to work in for a prolonged period of time. After 10 days Don, Pete Schwier and I reconvened at my studio, and there was a period of recording additional overdubs, tinkering with the drums sound, and so on. All the things that are part of finishing off a record. The final mixing process was cumulative, chipping away things bit by bit. I have a 32-channel, 64-input Neve Genesys desk and Pro Tools HD, the usual stuff; But we used the desk purely as a big summing bus, with everything set to zero. all the mixing and processing WAS DONE inside of Pro Tools, which meant that we could switch between tracks instantly.

“Jochum van der Saag also did some sound design and the final mix of Fever, and we tried to improve Peter Cobbin’s mix of Burning Love but couldn’t as it already sounded great.

“We tend to remember records from the past as larger than life, but that often bears little relation to reality. This album fulfils those larger-than-life memories of what those old records sounded like. You hear it’s not the original, but think it’s not that different either. However, if you were to compare the two different versions of a song side by side, the difference is shocking. The other reason the record sounds contemporary is because there is no disconnect between the vocal and the music. It sounds like one, as if Elvis had been there with us during the sessions.”

In listening to If I Can Dream it is possible, for a moment, to imagine that Elvis is still alive after all.

RESPONSES