On the Go: Moving From a Laptop to an iPad

Adopting an iPad for audio production means embracing a new mode of file management where cloud storage replaces hard disks, and wireless connections sub in for SD cards and USB sticks. Simmo explains how he moved his workflow over to the tablet.

‘Why am I carrying around terabytes of stuff I’ve done nothing with?’ That was the question buzzing around my head in September 2017 as I panned across the hard drives in my backpack. There were umpteen dozen sound recordings, videos and pics from numerous forays through Asia and the Himalaya, all just a head crash from oblivion. It was time to do something with them. It was also time to change my approach, from ‘post-production when I get home’ — which had clearly failed — to ‘post-production on location’. I needed to break the stockpiling habit.

I pictured myself trekking into a remote area with a lightweight high-quality rig, recording and filming an elderly villager playing endangered music, and leaving behind a finished copy. That wasn’t going to happen with my Macbook Pro. It’s an early 2013 model with 15-inch Retina display; a wonderfully reliable machine that never cost a cent in repairs, but its trekking days were over. Apart from being too heavy for what I had in mind, its battery life had faded to a measly few hours and I hated working with iMovie and Final Cut Pro. I wanted a lightweight DAW with a day’s worth of battery, and a video editing app I could relate to as an audio guy.

A week later Apple released iOS 11, and reviewers asked “is it time to replace your laptop with an iPad?” Most concluded “Not yet”, but I’d already done the numbers. An iPad Pro now serves all of my ‘post-production on location’ needs, saves two kilograms over my old Macbook Pro and over AU$2000 on upgrading to a new Macbook Pro. However, getting to that point was not easy. Here’s how I made it work.

THE RECORDING RIG

I’ve got a few rigs at my disposal, but this story focuses on the lightweight high-quality rig I use for capturing endangered music in remote places. It’s a modern take on the classic ethnomusicologist’s rig: a pair of Sennheiser MKH800 microphones, a Nagra 7 field recorder, a pair of Etymotic ER4 microPro in-ear monitors and a Sony RX100 MkIII pocket camera. I record 24-bit/96k wavs on the Nagra, capture 1080p HD video on the Sony, and do all the post-production on location with the iPad Pro.

IPAD’S PROS

I’ve got the top-of-the-line 10.5-inch iPad Pro from 2017, with 512GB of storage and the cellular option. It uses Apple’s 64-bit A10X Fusion SoC (System On a Chip), which performs well in benchmark tests against the Macbook Pros of its generation, and has a default 120Hz screen refresh rate that adapts to the frame rate of whatever you’re viewing. It definitely feels faster and more responsive than the old Macbook Pro it replaces. I use it with Apple’s Smart Keyboard and the Apple Pencil, and protect it with an Urban Armor Gear cover that integrates well with the Smart Keyboard.

There are four speakers — one in each corner — with on-board sensors to adjust between landscape and portrait so you always get the proper stereo image. Apple has been criticised for dedicating so much internal space to speakers rather than a larger battery but, as a sound engineer, I don’t have a problem with that; the battery lasts long enough and the speakers sound remarkably good. My early-2013 Macbook Pro sounds like rubbish by comparison.

Because it’s a post-social media design, it leaves the Macbook Pro for dead when it comes to YouTube, Instagram and Facebook — especially when using their dedicated iOS apps. Installing a SIM card for whatever country I’m in gives me internet wherever there’s a phone network, which is everywhere these days — including that remote village I mentioned earlier. Also, its tablet form makes displaying flight confirmations at airports, watching movies on overnight buses, and navigating new cities much easier than the Macbook Pro.

Greg Simmons is a writer, educator and sound engineer who is 20 months into his quest to spend the rest of his life travelling and recording music.

APP STACK

Three apps form the core of my iOS post-production system: AudioShare, Auria Pro and LumaFusion.

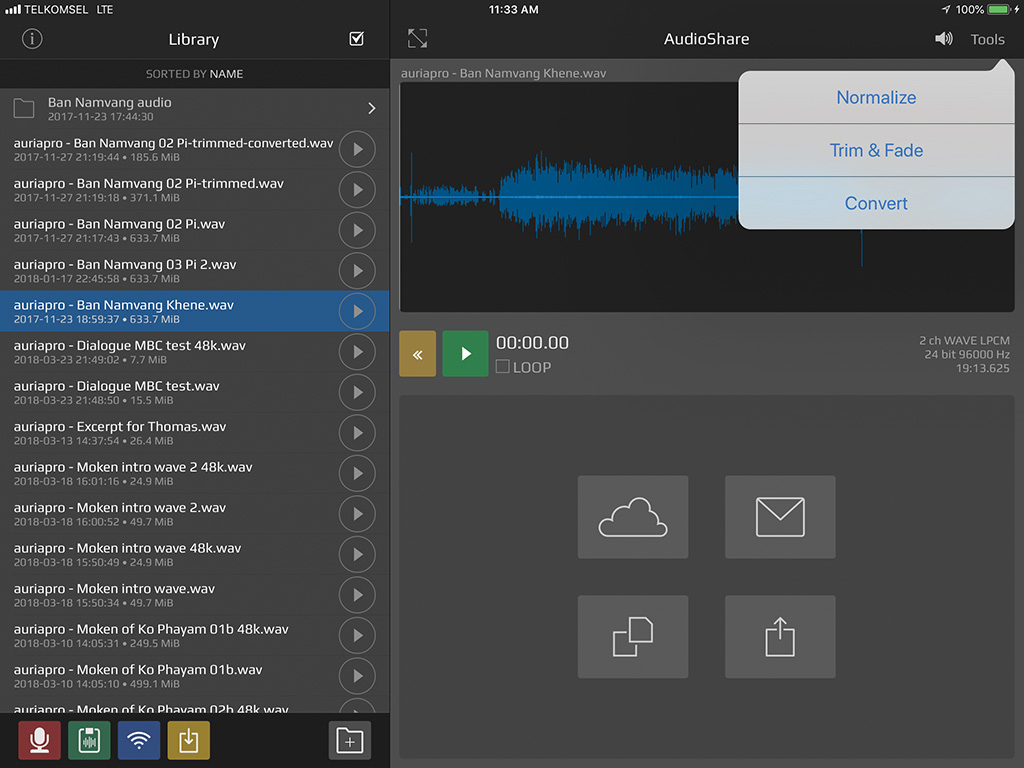

AudioShare is indispensable for organising audio files on iOS and offers duplicating, re-naming, normalising, trimming, fading, and sample rate conversion. Most importantly, it’s a valuable repository for storing audio files and a useful conduit for sharing them between apps. It’s like the Photos app for audio.

Auria Pro is a DAW that can mix dozens of tracks of mono or stereo 24-bit/96k audio with 64-bit processing. It also supports MIDI, has a bunch of synth and drum machine add-ons, and videos can be inserted for scoring/mixing to. Each channel comes with a four-band parametric equaliser, sweepable high and low pass filters, comprehensive dynamics, and four plug-in slots. There’s a handful of built-in reverb and delay plug-ins from PSP, along with a growing number of plug-ins available as in-app purchases from FabFilter, Wavemachine Labs and others. No registration, no iLok nonsense, and nowhere near the price of their VST, AU, AAX and RTAS equivalents. Welcome to the mobile device economy!

LumaFusion is a video editing app that makes sense to my ‘audio guy’ brain. It looks and feels like a DAW, with three dedicated video tracks (each with its own embedded audio), three dedicated audio tracks, stacks of titling and transition options, colour correction, audio processing and more. It was one of the major influencers in my move to iOS, after some nerve-racking experiences with iMovie and Final Cut Pro.

There have been significant changes in iOS software, hardware and accessories since this story was published. Read the follow-up story here.

IPAD’S CONS

Apple launched iOS in June 2007. Originally called ‘iPhone OS’, it was designed for the first iPhone and iPod Touch. Managing the content of those new devices was done in the same way as the earlier iPods — via a USB connection to a desktop or laptop running iTunes. That remains one of the common ways of getting files in and out of iOS devices, along with wireless connections and cloud storage; but none of that is any use when you’re in a remote village with SD cards in one hand and an iPad Pro in the other!

The Nagra and Sony both use SD cards for storage, so transferring files into the iPad Pro should be as simple as connecting Apple’s SD card reader, inserting an SD card, and… No! Apple’s SD card reader only sees certain types of camera files, and only transfers them to the Photos app. It doesn’t see the Nagra’s 24-bit/96k wav files, and it doesn’t see the Sony’s XAVC-S video files. Strike two from two.

I tried three SD card readers from funky brands I’d never heard of, with no joy. However, unlike Apple’s SD card reader, each third-party reader came with its own app that served as a driver, a directory and a user interface. Some of those apps allowed files to be transferred to other third-party apps, but not the ones I was using. Obviously there was no evil plan by Apple to keep everyone on their products; the limitation was in the coding of the apps that accompanied the card readers. Encouraged by this realisation I pursued the more expensive options from the more familiar brands, hoping they had better apps. The following solutions transfer files from field recorders and cameras into iOS without going via iTunes or cloud storage.

iOSOLUTIONS

Many cameras have built-in wireless for transferring pics and videos to mobile devices, but this consumes battery power — an important consideration in the field. The Sony camera I use has wireless, but the accompanying PlayMemories app allows everything except the XAVC-S files I use to be transferred. Inconceivable!

Apple’s Lightning to USB 3 Camera Adaptor works as a direct connection into the Photos app from cameras that allow USB access, and will transfer jpeg and RAW files, along with SD and HD video formats including H.264 and MPEG-4. By setting my Sony camera’s USB port to MTP (Media Transfer Protocol), it will transfer XAVC-S files directly into the Photos app from where they can be accessed by other apps. It’s faster than the wireless options mentioned below, but does not transfer sound files.

Toshiba’s FlashAir W-04 is straight out of Mission Impossible; an SDXC card with up to 64GB of storage, built-in wireless, and a pass-through connection to your existing Wi-Fi server so you’re not cut off from the internet while using it. There’s no room for a battery, so it must be inserted into an active SD card slot for power. The accompanying app is initially ambiguous, but works. The FlashAir can be inserted into a field recorder or camera to add wifi capability; there is no way to turn off the Wi-Fi, however, which means it might consume battery life faster. Wireless transfers are slow (802.11b/g/n), so transferring large files will consume battery life in the field.

SanDisk’s Connect is a USB 2.0 stick with up to 256GB of storage along with a built-in wireless connection and battery, in a package the size of a cigarette lighter. The accompanying app is good and allows files to be auditioned and shared. The internal battery allows four hours of continuous Wi-Fi use and recharges from a standard USB port in two hours. Wireless transfers are slow (802.11n) but its own battery means less drain on your field recorder or camera. As with the FlashAir, it offers a Wi-Fi pass-through mode. Unlike the FlashAir, it adds extra weight to your rig but at 22 grams, it’s hardly worth mentioning. If your field recorder or camera can write to a USB stick, the Connect provides wireless connectivity and data backup.

At this point it’s worth warning about SanDisk’s iXpand; a tempting USB stick with a Lightning connector and a decent accompanying app. It uses a proprietary Apple format that’s only readable on OSX and iOS machines. A field recorder or camera that can write to a USB stick won’t see it, and reformatting it to FAT32 or similar makes it invisible to iOS. It works well, but it’s only for external storage and transfer between OSX and iOS devices.

Moving up from wireless SD cards and USB sticks is an emerging category of ‘hub’ products that combine an SD card reader, a USB port and a wireless connection with on-board storage and a power bank. These include Kingston’s MobileLite Wireless Pro, RAVPower’s FileHub and Western Digital’s My Passport Wireless Pro. The power bank in each of these makes them considerably larger and heavier than the FlashAir and Connect, but can be used to recharge your USB devices in the field. If you’re already carrying a power bank, one of these might replace it while adding the extra features with little change in overall weight or volume. I have not tried the Kingston or RAVPower products, but both have good reviews online.

I’m using Western Digital’s My Passport Wireless Pro. It’s the size of a double CD case with all the features mentioned above, along with two wireless bands (802.11ac at 5GHz and 802.11n at 2.4GHz) and an excellent app with preview and sharing capabilities. A stand-alone copy feature transfers the contents of an inserted SD card onto its internal drive without requiring an iOS connection, and can be configured to transfer everything on the SD card or only what has been added since the previous transfer. It can also be used as a USB 3.0 external drive on OS X and Windows machines. A major selling point for my application is that it’s recognised by LumaFusion. Footage can be previewed and trimmed in LumaFusion directly from the Western Digital’s drive, with only the trimmed section imported to the iPad Pro. This saves Gigabytes of on-board memory when you only need a five-second segment from 10 minutes of B-Roll. Ruggedised SSD versions are available, but I opted for the 3TB spinning disk version because it doubles as a remote backup for all the other drives that were formerly in my backpack.

MY CURRENT WORKFLOW

After recording and filming, the SD cards are inserted into the Western Digital and automatically copied to its internal drive for backup. A wireless connection to the iPad Pro allows auditioning, copying, renaming, moving and/or deleting files on the hard drive.

The Nagra’s 24-bit/96k wavs are transferred to AudioShare where starts and ends are trimmed if necessary before being transferred to AuriaPro for mixing, editing and mastering. From AuriaPro the 24-bit/96k mixes are bounced back into AudioShare, and a copy is converted to 48k and transferred to LumaFusion for syncing to video.

The Sony’s XAVC-S video files are auditioned on the Western Digital drive from within LumaFusion, with only the desired segments transferred to the iPad Pro’s on-board storage. From there, they are synchronised with the audio files, edited and so on. The finished videos can be rendered to LumaFusion’s on-board storage, the Photos app, wireless drives, cloud storage services, or directly to YouTube or Vimeo.

CONCLUSION: iOS FOR OS

The biggest challenge for anyone working on location with field recorders, cameras and iOS devices is getting the files into iOS. The products, apps and workflows described above overcome that challenge.

Furthermore, the iPad Pro brings features that are not available with most laptops. It has the same camera as the iPhone 7 and, given sufficient light, captures very acceptable images for social media use; the Filmic Pro app turns it into an impressive backup video camera. Adding an iOS compatible microphone such as Rode’s iXY or Shure’s MV88 turns it into a backup stereo recorder. Sony’s PlayMemories app turns it into a comprehensive wireless remote control for my Sony camera. Adding Zoom’s F8 Control app brings Bluetooth remote control of my Zoom F8 (a fundamental part of the larger rig I use for my educational sound recording expeditions). And last, but certainly not least, the internal speakers provide a reasonable cross-reference for any audio destined for social media.

My transition from OS X to iOS has been so successful that my Macbook Pro and hard disks now live in a storage locker in Bangkok, coming out once a month to archive recent recordings and videos. My entire digital life takes place on the 10.5 inch iPad Pro – in fact, this story was written in the Notes app while staying in an artists’ village above Ubud, Bali. I don’t miss the laptop at all…

Another useful audio editor app for Ios is Twisted Wave. https://twistedwave.com/ios

Sorry for the very late reply! On your recommendation I checked out Twisted Wave, which has a lot of things going for it. I hope they update it soon, after all the changes that have happened in iOS world recently.

Also, I just finished a follow-up to this story, which makes most of the hardware recommendations mentioned here redundant. You can find it here:

Note: there have been significant changes in iOS software, hardware and accessories since this story was published. Read the follow-up story here.

https://www.audiotechnology.com/tutorials/going-further

Hi Greg,

Thanks for the great insight into your workflow with the iPad. A quick question: is it possible to drag/move audio files between folders in the iPad ‘files’ section like I can in Mac OS?

Thanks!

To a certain extent, yes. But it’s not like Mac OSX or Windows because it is a fundamentally different operating system and metaphor. iOS uses application sandboxing, which means every file lives in the ‘sandbox’ that belongs to its app. This has many advantages for devices that are intended to be used on-line and with wireless media because sandboxing makes it impossible for a virus to replicate (beyond any one app’s sandbox to another) without either the user’s permission or the system’s permission, and it also makes it very difficult for other forms of malware to operate.

However, it also makes it hard to keep lots of different file types together in one place for one project!

For example, by the time I’ve planned an expedition I’ve got spreadsheets, word processor documents, pics, pdfs, graphs and all kinds of things and it’s not easy to group them all together in one place on-board the iPad Pro without using an app that is designed for storing files in its own sandbox, such as the Documents app by Readle.

To get to that kind of drag-and-drop action, you need to look at off-board (and therefore out of the sandboxes) storage things like iCloud, Google Drive, Microsoft’s OneDrive and similar – which are more like ordinary drives where you can drag and drop things if their interfacing app allows drag and drop operations. Those services allow you to put different file types into one folder, which is very helpful.

[Also, sorry for taking so long to reply!]

I’ve just finished a follow-up to this story, which makes most of the hardware recommendations given here redundant and also discusses the cool things that have happened in iOS and device hardware since this was written. You can read it here:

Note: there have been significant changes in iOS software, hardware and accessories since this story was published. Read the follow-up story here.

https://www.audiotechnology.com/tutorials/going-further