On Loop at the Loft

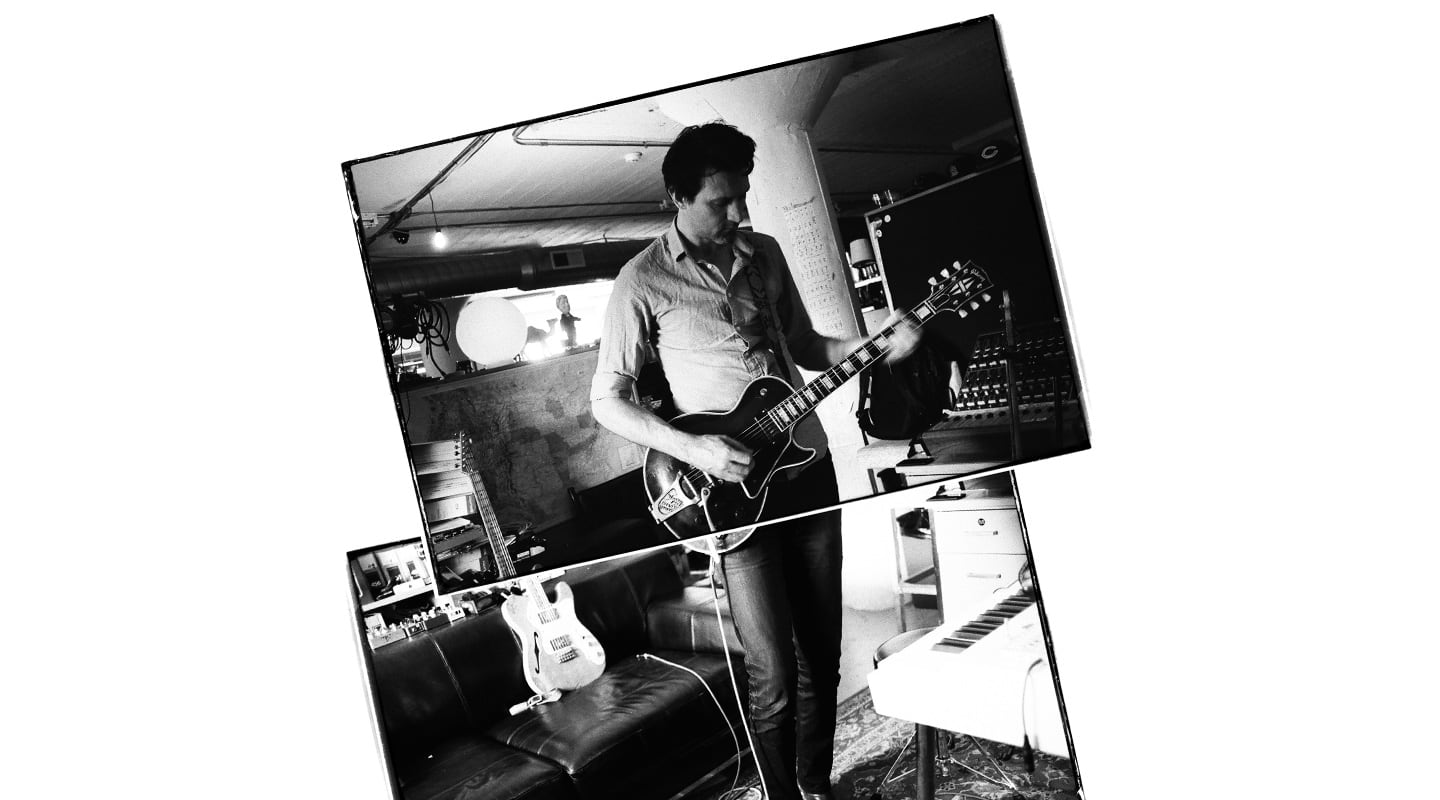

Paul Dempsey had every instrument he could possibly imagine on hand at Wilco’s The Loft, but he was the only musician there to play them.

Artist: Paul Dempsey

Album: Strange Loop

Photos: Maclay Heriot

When Paul Dempsey packed his suitcase for a three-week stint at Wilco’s The Loft studio in Chicago, he couldn’t help himself. From the first time he’d Skyped producer Tom Schick, Paul had been assured Wilco’s inventory of gear would cover his every want and need. Paul said Tom would assure him, ‘Trust me, they acquire things faster than anyone could keep a list.’ Still, he had to throw something in that represented his own musical taste and peculiarities. He grabbed the smallest things he could find, his cherished JHS Colour Box and MI Audio custom stomp boxes, and stuffed them between some shirts… And they didn’t come out again until he arrived back in Australia.

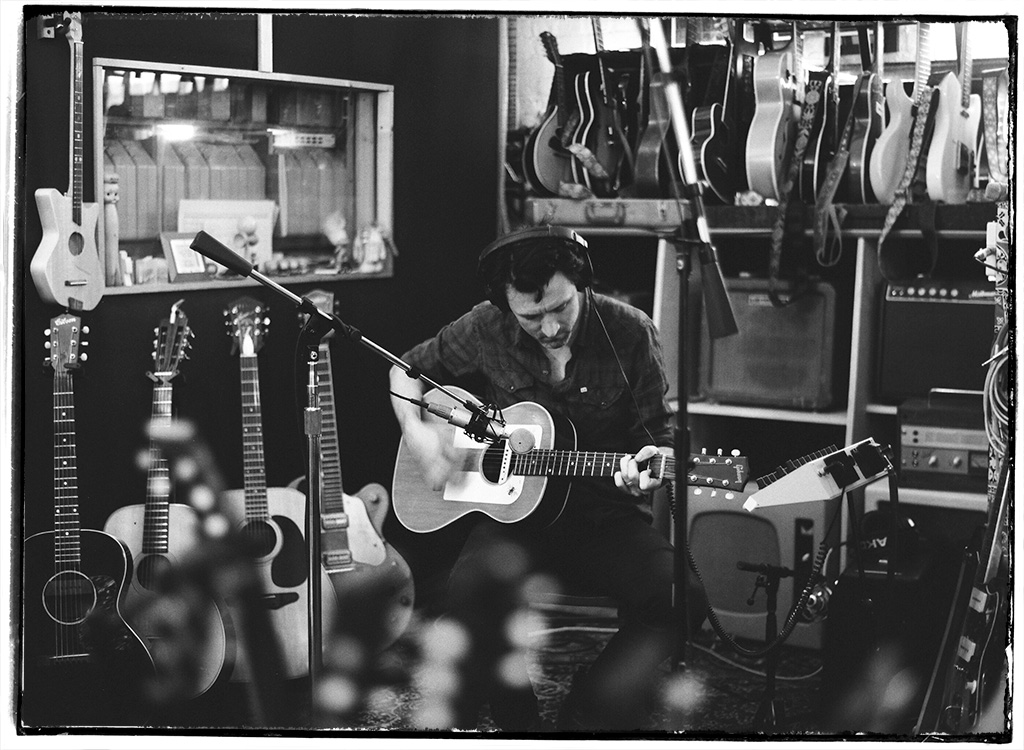

In the first afternoon at the Loft, said Dempsey, “I realised I had to actually stop looking at instruments. I’d found half a dozen guitars that were all doing what I wanted. I didn’t need to open any other guitar cases, or I wasn’t going to get any work done.”

Schick is all too familiar with that glassy-eyed look musicians get when they first enter The Loft. There are rows upon rows of guitars, keyboards, amps, and random instruments; imagine an instrument and they probably either have it at The Loft or will do soon. Beyond the maze of instruments on the floor, there are storage racks reaching to the roof of the warehouse stocked with occupied guitar cases. After the interview, Paul opened up a handful of smartphone videos he’d shot over the three weeks. One showed he and Tom prodding at an old Wurlitzer tape percussion machine, where every button activated a different tape to roll past the heads. The resulting analogue blips and tocks became the phasey, underwater-sounding opening of the song Idiot Oracle. “On tour, Jeff [Tweedy, Wilco’s lead singer] just goes back to his hotel after the gig and buys stuff on eBay, then it turns up at the studio,” explained Dempsey as he played another video, this time of him doubling a lead line with a mystery gourd-bellied electric guitar the post man had dropped off that day.

“It can be overwhelming for a musician,” said Schick. “I usually tell them to grab the closest instrument, try it out, and see how it feels. You can get bogged down and spend all day trying to find the right guitar and the right amp.” Studio manager, Mark Greenberg, is probably as close as anyone comes to being a Loft librarian, but even he doesn’t have a definitive list. Schick’s recommendation to artists is, “If you see something you’ve never tried before, just plug it in and don’t be precious. You’re never going to plug in something that sounds horrible. It’s more about whether you want a big amp or a small amp, a 12-string or a six string, a hollow body or a solid body, then you narrow it down that way. Paul is a great musician, he knew what guitars he likes and he’d gravitate towards those.”

STRIPPING BACK THE RACK

Dempsey is particularly savvy about gear, both for making music and recording it. In his Melbourne home studio, he has more than a few guitars himself, a Wurli, a handful of guitar amps, and loads of stomp box effects, but his 19-inch rack is looking pretty empty these days. It just has a Universal Audio Apollo interface in it, and an API lunchbox leaning up against it stocked with only a couple of Neve 1073LB preamps. The rest of the rack used to be full, but times have changed, and he’s finding the Apollo and Neves are all he needs.

For years he was using a Digidesign 002 for demos. Then in 2009, he signed a new deal to do a solo record with Wayne Connolly, which came with a budget. “Usually you’d spend that all on studio costs, but I was starting to feel more confident with my home engineering skills,” explained Dempsey. “I thought I could take the money to get some gear, then I’d be set up for future albums as well. I enlisted Wayne’s help with the shopping list because he’s a better engineer. That’s when I got the Digi 192 interface, and a few rack pieces and some mics. We dragged it all up to a friend’s place and recorded the album there.”

It was more than just a demo rig. He had a Pro Tools HD system, with the 192 interface and Accel cards, a PCI card-compatible Mac Pro tower to run it all, with Chandler and TL Audio outboard as his front end. All up, it was around $15,000. Then a couple of years ago, Avid started to phase out the 192s.

“They weren’t really providing support for it, so I got the s**ts.” admitted Dempsey. “I was starting to write and do demos for Strange Loop and all my gear was obsolete. I was still using Pro Tools HD software, but I needed new gear that interfaced with Thunderbolt on a new Mac. I got talking to the guys at Manny’s in North Fitzroy, weighing up the pros and cons, and they put me onto the Apollo.”

Since acquiring the Apollo and an iMac, most of his 500 series gear has disappeared off to the Music Swop Shop in Carlton, and he got less than a thousand bucks for his previous Tools rig.

He’s pretty satisfied with the compact setup, which also includes Native Instruments Komplete and a Komplete Kontrol keyboard. “With my previous Pro Tools rig you couldn’t walk in half the room because of all the looms of cable,” he said, and trips down to record drums at the rehearsal studio have gotten a lot simpler. Still, he does fantasise about one day building a small studio out the back of their property and stuffing it with all kinds of vintage collectibles, which is why he went to The Loft. “It’s the complete opposite of this because they actually do have every single keyboard, guitar amp, guitar and drum kit,” he said. “They’ve got the real version of everything you’ve ever dreamed of, including mics, compressors, preamps, and Neve consoles. I went over there with my demos and said, ‘let’s do this again with the real stuff.’”

DEMO DOWN

Dempsey is also the frontman for Australian rock stalwarts Something For Kate. It’s a complete band dynamic, where all three band members push and pull a song in different directions until they’re all happy with it. Recording a solo record like Strange Loop affords him the last say on everything. It’s more of an ego trip. “But what music isn’t?” questioned Dempsey. “It’s satisfying to make a record the way you’ve heard it in your head.”

To that end, he uses his demo rig to flesh out each song in detail before going into the studio. Then the final step in the process is throwing it open to critique. “Appointing someone as devil’s advocate,” Dempsey described it. “Installing Tom Schick as the last line of defence against me being completely wrong about something. I also like to keep an antenna up for the accidents that happen in the studio, when you’re working with someone else and they go, ‘what was that?’. I went over with 80% of it on the demos, and the rest was happy accidents or feedback from Tom.”

Luckily, Dempsey isn’t a hack. Something For Kate shows he can obviously sing and rip on guitar, and bass isn’t a stretch for him. However, Dempsey was actually a drummer first, and he’s handy on the keys.

“I knew he played a lot of instruments, but I was a little scared at first that it would for the most part be me and him,” admitted Schick. “You just never know how somebody is when they say they’re a multi-instrumentalist. The first song we worked on, he sat down and starting playing drums, then right away played another instrument over the top of it. It really sounded like a band, which was hard to do. He’s an amazingly talented guy.”

Dempsey writes in two distinct sections; music first, lyrics and melody later. “It’s a completely separate vacuum. The music production process and lyric writing process are completely separate from each other. I essentially build up an album’s worth of music and then write lyrics. I guess a lot of songwriters are holding a guitar and writing in a journal. I don’t do that.

“Music’s not an issue. I’ll go from the germ of an idea to getting it pretty well demoed in a free afternoon. Whereas, it can take me a very long time to finish lyrics. I’m not lazy; I’ll sit for hours and hours a day and do it for weeks and weeks. Lyrics are harder because you have to make decisions about what you want to verbalise and say about yourself.”

The multi-instrumentalist streak comes out of him from the get-go, typically starting with a groove or beat in his head, and forming the song around that. In many ways, his songwriting process is well-suited to a one-man band style of tracking; drums first, instruments, then vocals, which is exactly how he did it at The Loft.

I realised I had to actually stop looking at instruments or I wasn’t going to get any work done

SCHICK EFFECT

When he reached The Loft, it was just he and Schick. Schick is a stone cold legend of American rock and folk. Dempsey was attracted to working with him, obviously because of his work with Wilco, but also because he produced, recorded and mixed Ryan Adams a number of times, including one of Dempsey’s favourites Cold Roses, worked with Low, Rufus Wainwright, Norah Jones, M Ward, and helped Jeff Tweedy with the Mavis Staples record, as well as when Tweedy recorded arrangements around Pops Staples’ final vocal recordings. These days, Schick is essentially the in-house engineer at The Loft. When he’s not working with Tweedy — which only happens when Wilco goes on tour — Schick uses the studio to work on other projects like Strange Loop. “Jeff’s a really hard worker, so when he’s in town he’ll be in the studio writing and recording ideas,” said Schick. “He’ll always get one thing done in a day.”

Paul has worked with a lot of producers, Something For Kate made a point of not sticking with the one person throughout their career. It all started with their “dream producer” Brian Paulson, who made their first two records, then a couple with Trina Shoemaker — “a comfort zone we could have easily stayed in” — then Brad Wood, and John Congleton. “I’ve been able to watch how they do what they do, all they’re different tricks and techniques,” said Dempsey. “And they’re all really different.” He learnt engineering from watching each engineer, working back through their signal paths, and asking lots of questions. “The first time you look at an SSL as a 19-year-old, you are thinking, ‘that’s why that guy earns the big bucks’,” recalled Dempsey. “Trina was the first person to say to me, ‘it’s just plumbing.’”

The biggest difference Dempsey noticed about Schick’s way of working was the lack of processing. “Everything was done with the simplest possible single chain,” he explained. It helps when you have an entire floor of instruments to choose a sound from. “He knows what works. I’d describe something to him, and he’d come back with a little speaker made out of corrugated iron and just stand in front of it with a 57, then blend in a bit of that.” Layering soon became a theme, often doubling a guitar solo with something unique, or layering tones to produce a sound you couldn’t get any other way.

“He also worked really quickly,” said Dempsey. “Most of the time he stood at the console, there was hardly any sitting, and no couch. The whole album was recorded and mixed in two and a half weeks, mixing and balancing as he went.”

Schick didn’t strictly keep to those mixes, but “every time I work on a song I put down a rough mix before moving on, because you learn something every time,” he explained. “It’s not so much about compression and EQ, but more about balance and panning. Getting stuff out and making a commitment. If a part is played all the way through, your first instinct is to listen to it and pull it out at certain spots and do a rough like that. That way when you do the final mix it should be pretty close.”

Other than not sitting down much of the time, he also sits the computer keyboard and screen off to the side on a high counter. “I don’t like working at a studio where you’re sitting down staring at a screen between two speakers,” said Schick. “I want to be listening to music and not looking at a screen. I treat Pro Tools like a tape machine and you wouldn’t have a giant tape machine between the speakers.”

The other main difference Dempsey discovered was how much Schick trusted what he was hearing, without having to jump out to his car. Most of that is due to Schick working day in and out on the Genelecs in The Loft. “I basically spend every day in there listening to stuff,” he explained. “So I can tell right away if something is a little off.” Dempsey on the other hand, had to occasionally run out to the tracking floor and slip on his trusty pair of Sennheiser HD280s just to be sure.

ONE DRUMMER, TWO KITS

Most of the recordings started by loading up the demos, muting everything except the guide guitar and going from there. Occasionally, Dempsey would sit at the drum kit and play a song from memory. Each time, it would start from one of two drum kits setups, which gave two different sounds out of the box, without any processing. “If you want dry drums you play the kit behind the baffles,” explained Dempsey. “If you want them to sound bigger, go play the kit out in the warehouse.”

Schick explained the setup in more detail: “One was a pretty tight-sounding drum kit that was totally isolated in the booth. I had a pair of Coles 4038s for overheads, a Shure SM57 on the snare, an AKG D112 on the kick drum. I also have a Neumann CMV-563 kit mic right above the outer rim of the kick drum and pointed at the rack tom. If the drums need to be a bit brighter, I add a little more of that mic. If they need to be darker, I trim it down a little and let the Coles do most of the work. Those mics were all going through API mic pres. I used the Neve 2254 compressors in the console to compress the overheads, while the kick and snare went through dbx 160s.

“The other kit in the live room had an RE20 on the kick drum, a Sennheiser 441 on the snare, a Royer for an overhead, and a room mic. The overhead was going through a Neve BCM10 sidecar and a TG1 compressor, and the kick and snare were going through APIs and Urei 1176s. The live room had a smaller setup but a bigger sound.

“I like the idea of a mono drum kit, so you can pan the overhead where you want it to be, rather than having a drum kit that takes up the whole stereo field. Often I will have the kick in the middle, because the low end doesn’t translate when you pan hard, then the snare and overhead all the way off to one side. You get a nice spread that way. Sometimes having the snare slightly to the left and overhead up the middle opens up things too.

“When I use stereo overheads, they’re usually only a foot apart, and I’ll get them as close as the drummer will let me. I don’t like it really wide, which is why I like using a mono overhead sometimes, because I can really get that close in there. When you’re using ribbon mics, they pick up from the other end too, so you’re still going to have some space around it. They also help cut down on cymbals, and I love the way the toms, kick and snare sound through them. I get most of the drum sound through the overheads. The kick and snare mics are used to get a little more definition.

“Sometimes we’d do a tight dry kit in the booth, then throw in some tom overdubs in the live room that doubled the toms.”

ON THE GO SETUP

After the drums were laid down, it was up to Paul where he wanted to go next. “We had everything set up,” explained Schick. “We had the two different drum stations going, two bass rigs set up, an acoustic guitar station, an electric guitar station, and another amp that floated which you could plug a keyboard into, two pianos that were always miked up, and a couple of DI lines. You could jump from one to another.”

Like the drums, the two bass set ups gave two diverse starting points. “We had a Schroeder bass head going through a large cabinet and a Manley tube DI for the bigger rounder sounds,” said Schick. “The more blown up, distorted bass sounds came from the Ampeg B15. Both had an EV RE20 on the cabinet. Paul used a couple of different basses; it was between Jeff’s P Bass, a Rickenbacker, and a hollow body Kay Bass.”

Of the many instruments, Jeff Tweedy’s cherished Kel Kroydon acoustic guitars became a favourite of Dempsey’s too. They were originally an affordable depression-era Gibson spinoff sold in department stores, and only appeared for a few years. “The company that used to make them also made children’s toys, so they just used the same stencils,” said Dempsey, pointing out the mirrored birds in a picture of him playing one. They’re light and flimsy, explained Dempsey, “It feels like you’re holding plywood.” But that lightness transfers to a non-boomy, unique sound with “just the right amount of mid range,” said Schick. “They record great. They don’t sound perfect, but are pretty even sounding, not scooped out like a lot of modern guitars. They cut through a mix, but still have a full frequency. We used the Neumann CMV-563 with an M7 capsule on that guitar, which has a nice punchy sound to it.”

SPEEDING FOR A BLEEDING

Schick’s speed has a purposeful side effect especially important to a one man overdub session. “I try to keep things pretty loose and not worry about making anything perfect,” he explained. “If we needed to go back and fix something, we would, but it was about getting all the parts down first, trying to capture great live performances, and hearing it all together.”

Quickly chasing performances and living with imperfections kept them from getting “too bogged down in details,” said Schick, which can too often happen with overdubs and kill the vibe. “With only two people in the room, if you get fixated on a part you lose the momentum. The key is to keep momentum going and letting the record build itself.”

While moving fast helped recreate the performance aspect of a band playing together, “the one thing missing is the bleed between instruments,” said Schick. The Loft layout helps in that regard, because the control room isn’t isolated from the tracking floor. “Sometimes we’d have the speakers on and he’d play along, rather than isolating him in the headphones. You’d get a little of the track bleeding into the microphone of that take. Every once in a while we’d blend a room mic when he was doing a guitar pass.” Overall though, said Schick, the most important part was “capturing the live performance. If you’re doing that, it’s going to feel live.”

On a couple of occasions, musicians were brought in to play instruments Dempsey couldn’t, like horns on a couple of tracks and pedal steel on the last. The studio manager said he knew some people who could stop by, one of whom happened to be Brian Wilson’s band leader, Paul Von Mertens. On the rocker, Morningless, Dempsey wanted to double the bass line with a bass sax, not realising how difficult the part would be to play in real life. “I can’t play a bass saxophone, so I gave absolutely no consideration to how much air a person has to push through a horn that big to produce a sound,” he explained. “And, of course, the part is fast. Paul came in and said, ‘This is a crazy part. What are you doing?’ I was like, ‘Really? S**t, sorry.’ But he really wanted to give it a try because he wasn’t sure if it could be done. There was a little cutting and pasting involved to tighten a couple of things, but he gave it a valiant go and nailed the whole song. Then he did it on baritone as well. By the time Paul had finished, his lip was bleeding from frantically trying to push air through the sax.”

VOCAL PULL

While Dempsey gravitated to the drums early, it was surprising that he was a late comer to vocals, considering he grew up in a house full of trained opera singers. It was only out of necessity, when Something For Kate couldn’t find a vocalist, that he stepped into the role. “I came late to singing, but was lucky enough to have a household of singers to give me some tips,” said Dempsey. “I really project from my diaphragm and sing with my whole body; I don’t know how to do it any other way. When I’m breathing the right way, and singing the way the technique will dictate it just comes out in this loud, gravelly production.

“I’m completely aware I have a particular voice that some people like and that make the hairs stand up on the backs of people’s necks as well. There’s nothing I can do about it. When I’m working with a producer I’m open to them saying, ‘give it a shot and do something different.’

“On our first records I was always singing into a Neumann U47 through a Neve. Now I use a Shure SM7 on pretty much everything. It just seems to flatten out my voice in the right kind of way, because I’ve got a particularly sibilant voice when I sing.”

At The Loft he used the SM7, through the Neve BCM10 sidecar into a Urei 1176. Dempsey is also dead against pitch correction: “It doesn’t agree with me on a philosophical level, if I don’t sing it right I just sing it again. I’m a bit of a stickler about warming up vocals too. I learnt on those early records that I’d sing a song 10 times and may be on the eleventh time it’d actually start to sound good.”

“He would do a few takes and a lot would be full performances with a couple of lines comped,” recalled Schick. “The SM7 has a closeness to it that sounds better in a performer’s headphones when they’re working the mic. Mostly I just had the low frequency rolloff on the EQ, and added a little bit of top end. The 1176 adds a bit of upper mid range to it, and I’d sometimes add a de-esser to it, because dynamic mics can sometimes get a little ess-ey. I don’t usually do a ton of hard EQ. I try to get it right with mic choice and placement. If I have to do extreme EQ, I feel like I’ve done something wrong and I’m trying to compensate.”

HAPPY COINCIDENCES

When it came to the final mix, Schtick had already been through multiple rounds of roughs for each song. Still, he starts with the same process of relying on balance and panning at the beginning of a mix. “I try to start panning either hard left, hard right or centre and make it work that way,” he said. “I give myself limitations to get everything sitting right in that puzzle, which helps me figure out if the arrangement’s right; if I’m missing something or there’s too much stuff. If I get it close, I’ll bring parts in a little and do more detailed panning.”

He also doesn’t bother zero-ing out the console whenever he brings up a new song to mix. “I don’t totally reset it, because sometimes you’ll bring it up on the same faders as the song before it and you’ll hear something you wouldn’t have ever done. For instance, you might find the acoustic guitar sounds really cool with all that reverb.”

Unlike Dempsey, who likes to cycle through producers, Schick has often worked with the same artist over multiple records. These days, Schick is pretty well served by his relationship with Wilco. Having constant work, and a consistent place to work out of is nothing to be sneezed at, considering many of the studios he used to work out of in New York are closed down. He credits that longevity in his working relationships to not sticking to any particular formula. “I like to have fun in the studio and not be precious about anything,” he said. “Have the focus be on the music and not on the engineering. I like to make it so people feel comfortable being creative. Usually when I do a record with somebody, we end up doing another one, and I can usually do it within a budget because we work fast.”

In just one three-week trip, Dempsey and Schick were able to record and mix the entirety of Strange Loop, with one person playing almost every instrument on 11 tracks. That’s fast. Who knows, maybe Dempsey will loop back again one day.

RESPONSES