Name Behind the Name: Peter Freedman – Rode Microphones

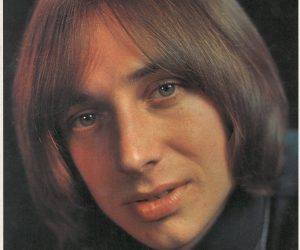

In the first of a series of occasional interviews with the ‘people behind the brands’ Christopher Holder talks to Rode Microphones’ Peter Freedman about how he turned his fortunes around to make Rode one of the biggest audio success stories of the last decade.

The extraordinary rise of Rode Microphones has been swift and smooth. Virtually every mic the company has released in its 12-year history seems to have effortlessly gelled with the market – filling a niche, at the right price. Rode sells around 60,000 condenser microphones every year to every corner of the globe. This is not an editorial pat on the back for this Australian manufacturer, simply a statement of fact – Rode is an enormously successful audio company.

Overseeing operations is the company’s owner and CEO, Peter Freedman. What with Rode’s meteoric rise you’d probably think he had the Midas touch – gold dots as far as the eye can see. This couldn’t be further from the truth. The fact is, Rode Microphones could almost be described as the last throw of the dice for a man who took his father’s long-established and successful pro audio installation business and all but flushed it down the toilet.

After Henry Freedman’s untimely death in the mid ‘80s, Freedman Electronics, under a young Peter’s stewardship, went from being a pioneering and highly respected pro audio institution to being the Bi-Lo of audio – purveying whatever would sell, and a lot of things that didn’t.

So Peter Freedman understands what it’s like to know debt, despair, and virtual bankruptcy, which no doubt makes the success of Rode all the more sweet. In fact, this enormous disparity of ‘zero to hero’ goes a long way to describing the man himself – he’s a character of extremes.

Peter Freedman, came from a comfortable middle class background, he’s patently smart, shrewd and well read, but could happily pass himself off as a Bogan/Westie. The personal trappings of success (the cars, the first class travel, the house on the hill) sit unselfconsciously alongside his earring, his colourful language and bravado of a benevolent dictator. He loves the fact that he’s made high quality studio mics accessible to the masses; but selling crate loads of mics isn’t enough, he craves the accolades of his ‘peers’. Furthermore, Rode’s success is based on playing the international stage, but he hates the fact that ‘globalisation’ translates into an excuse for not ‘making’ anything in Australia anymore. In short, he knows he’s a paradox… and he loves it.

LOSING THE LOT

Christopher Holder: Can you tell me about Freedman Electronics?

Peter Freedman: My father’s greatest love was always audio electronics. My mother was Swedish and they moved from London to Stockholm before I was born. He was chief engineer for an electronics/telecommunications company in Sweden for a number of years before being offered the opportunity to take on the distribution of Dynacord products in Australia. So in the mid ‘60s we immigrated to Sydney and he opened up Freedman Electronics in Liverpool Rd, Ashfield.

CH: And you obviously developed a love for audio from that upbringing?

PF: My earliest memories were in my old man’s workshop. As a teenager I’d work for him after school and on weekends… What’s not to love? It’s nightclubs, it’s sex, it’s late nights… it’s a young man’s paradise.

CH: But then in the mid ‘80s you lost your Dad and inherited sole responsibility of Freedman Electronics. What was that like?

PF: For starters I don’t recommend anyone work with their parents – not a good idea. I loved my Dad but we were always knocking heads. I was always arguing that we should expand; we should do this, that or the other, and he’d flatly say, ‘no’ – of course, in retrospect he was totally right. So after my Dad died I was like, ‘I can do whatever I want now’. First thing I did was borrow a lot of money to build up the business.

For the first couple of years we did alright. In fact we tripled our turnover in one year – which might sound good, but you can’t sustain that sort of growth.

We got to the end of the ‘80s and by then I’d geared up this big machine to do nightclub installations. I was importing lighting, importing loudspeakers… And then, of course, the economy took a dive. I was sitting on about $400,000 dollars worth of debt and my sales dried up – everything came to a grinding halt.

After a few months things got progressively worse and before long the debt escalated. I thought I was going to have a heart attack at this point – I was 108kg, the bank took my house, I’d f**ked my father’s business… I wanted to kill myself for a while there. But what can you do? You have a family, commitments to staff, and you might want to run away but you can’t. You’ve just got to plod along and do what you can.

CH: Pretty bleak…

PF: Sure. But a turning point came when I met up with a bloke who I’d known for a long time. I first met him when he was a sales rep for a company called Carlsboro in the UK during the 70’s. That was Colin Hill. One thing I do pride myself on is being able to take opportunities. And the other thing I know is that to get out of trouble you need good salesmen. Colin loved everything about Australia so I offered him a job on the spot. He was my first ‘lieutenant’, and gave me the breathing space to get some perspective.

CH: And thus the first stirrings of what would become Rode?

PF: Well, that story dates back to 1981 when I went to a trade show in Shanghai. Freedman Electronics had a lot of dealings with China – we were building our own speaker cabinets and importing various components from there – and on this occasion I saw what looked like a Neumann U87 copy and I bought one as a sample. At the time we weren’t in the studio market. I’d sold the odd recording mic but there were hardly any home studios at that time. There were ‘porta studios’ and then there was the upper end of the market that bought Neumanns and AKGs – so there wasn’t a market. So I stored this mic away. Around 10 years later when I was thinking about what else we could sell, I pulled the mic out and I said to Colin, ‘take this around to some of the shops and see what they say’. He came back and said, ‘there’s a lot of interest in this thing’. So I brought in 20 of those Chinese mics and… they were shit – noisy, two out of the 20 weren’t working at all… I opened them up, and saw they’d used crappy components, and the soldered joints were bad. So we fixed up the parts, made a board mod here and there and got them to a point where we could sell them. They weren’t super quiet – about 25dBA noise, which is kinda like hearing a shower in the background compared to what we’re doing now – but they worked. And that was the beginning of Rode.

FROM CHINA WITH LOVE

CH: That was the first NT1?

PF: Nothing to do with the current NT1, but, yes, the NT1. They were Chinese and we just imported them. Our core business was still club installs, but we set aside a service bench in the warehouse so we could pull them apart, clean them up, have the Rode name engraved on them… pop in a brochure and away they went. That started to bring in a little bit of money – nothing to write home about, but it started to grow.

CH: What sort of numbers are we talking about?

PF: We were doing 100 a year – and that was pretty good for that type of thing. I remember thinking ‘if we can do 500 mics a year we’ve made it’. I just couldn’t get my head around that kind of quantity then. Now we do more than 12,000 NT1As a year!

CH: So you had a mic that was selling okay in Australia. Where to from there?

PF: I regularly went to China to meet the people I was dealing with. On one such trip I found another factory that was making a slightly better product. So I got samples from them and that was the beginning of the NT2. We made some mods, made them look a little bit more acceptable and started selling those.

CH: So, nothing international yet? No sales to the US for example?

PF: No, but I’d been to NAMM shows in LA before and I thought, ‘I wonder if there’s any chance of flogging these overseas?’. So I went to NAMM and walked around the exhibition with an NT2 in my pocket – like a guy selling watches. I met a few people there but there was no real interest.

So I traipsed around the streets of LA. My first stop was to a few studios – like Capitol and Ocean Way and A&M. Obviously they’re big-name studios, but I just rang them up, put on my best Paul Hogan Aussie accent and told them I’d love to have their opinion on this mic. They were nice, and I started to get names, which I dropped when I went to music stores in LA. After visiting various places without luck I went to West LA Music and probably spent most of the day demo’ing and talking to them. Eventually I struck a deal to supply them 100 mics! That just wiped me. That was like a year’s worth of sales in Australia, and to one store – in LA! It was then that I knew we were onto something. I walked out of there with tears in my eyes thinking ‘this could be it’.

From there we had the nerve to exhibit at the following year’s NAMM in 1993. We took a little booth jammed between a guy selling steel drums and a huge garbage bin – it was like a joke. But in the first three hours we stitched up distribution for Japan, Canada, England, France… we’d cracked it. We subsequently appointed Event Electronics as our US distributor who were a major part of our success in the US market. They continued as our distributors until we opened our own office and warehouse three years ago.

CH: ‘Cracking it’ was all based on what you’d done with the NT2. Can you tell me some more about what modifications you’d made to that mic to ensure it was of good quality?

PF: As I say, the mic came from this other Chinese manufacturer I discovered. From there I consulted a guy in the US called Jim Williams from a company called Audio Upgrades – he’s still around doing upgrades to consoles and microphones… bit of a guru. He came up with a circuit – which I subsequently found out wasn’t his, but based on a Schoeps circuit. Nonetheless, not taking anything away from Jim, he showed me the difference good audio design could make. The sound quality he got with his circuit compared to what we were doing with the old NT1 circuit was like night and day – really good FETs, better components, better layout, nice electronic balancing… And that completely changed the mic into what people loved about the NT2 – it became quite a special product. And that was the building of Rode – that circuit, our quality control and our marketing.

CH: And it wasn’t that long before you released the first Rode Classic valve mic?

PF: That’s right. At the time I noticed that the AKG C12 re-issue phenomenon was quite hot, and I thought there was an obvious need for a more affordable valve mic. It was also around that time I started doing my own metal work in Australia – in Mudgee.

CH: So this was a watershed. You’d gone from effectively selling ‘hotted up’ Chinese mics to taking steps to doing it yourself. Was it a case of going from just finding something that you could spruik to actually caring about microphones?

PF: Yeah, I guess it was. When I started working on the Classic I thought, ‘you know what, we can actually be a real microphone company’. From then on my aspirations were to build everything to do with the product. And the amount of work that went into developing the first Classic was insane.

CH: How did you go about sourcing and selecting your vacuum tubes for the Classic?

PF: I looked at the esoteric stuff and did some listening. I found that the sound of the 6072 valve was well suited to our circuit. I had a look at what the old AKG C12s had used – because that’s a lovely sounding mic – and I investigated how to buy those components. The best one, with the lowest microphonics and the sweetest sound, was the GE JAN [General Electric Joint Army Navy]. And, luckily I was able to source those original tubes (they’d been out of production for 20-odd years) and managed to buy 25,000 of them. These days you can’t buy those tubes for less that 40 or 50 dollars US apiece. And the Classic to this day still has that valve.

TAKING CONTROL

CH: So describe to me how the plans for in-house manufacturing progressed from those early Chinese microphone days up to the present?

PF: We outgrew our little warehouse in Rydalmere – a few laminex tables and a few women sitting there with soldering irons. From the proceeds of the NT2’s success we saved a lot of money and bought an ex-RTA technical workshop in Rhodes. That was the start of Rode becoming a real manufacturer, with real machinery, test gear and engineering staff. For example, during that time I bought our first ‘pick and place’ machine for automating the building of printed circuit boards. That was a big deal and really improved the specs of our mics.

CH: But the site still didn’t involve the holy grail of your own capsule making?

PF: And that was one of the main reasons for our third move to our current factory in Silverwater. I bought this new factory a few years ago and I spent over a million bucks doing it up. That way I could have the full-on clean room lab – lapping machines, the sputtering machines – to do capsules in a big way.

CH: Every other high-volume audio manufacturer seems to be throwing their lot in with the Chinese but you’re doing the complete opposite. Are you right and are they all wrong?

PF: Everyone knows that labour in China is very cheap, but that’s not the issue for us. That’s why I like taking people around our factory. For example, take that printed circuit board machine… how are the expensive local labour costs hurting me there? There is no labour! And if you do it the hi-tech way, the tolerances are just that much better than using manual labour.

CH: Yet, you’ve gone from having the cheapest mics around to being undercut by the Chinese-made mics. Doesn’t that affect business?

PF: It’s not all about price. With manufacturing in the western world, if we’re smart, we have a lot more to trade on than that. Rode has built up a huge brand name. We also have an edge on technology, we invest millions into R&D – something you can’t do if you’re selling mics for $20. I don’t see people flocking to buy Chinese guitars if it’s a Fender or Gibson they aspire to own, just because they’re cheap! And when the Chinese products go up in quality, which they must to survive, so will the price. Right now all these ‘suppliers’ are saying, “my Chinese mic is cheaper than your Chinese mic”. It’s a dead-end street. I would need to be double or triple the price for Rode to lose real sales. Rode has brand integrity, and it has the extra value-added stuff. For example, we have never ever charged for service and repairs. We don’t make a song and dance of the fact, but it’s true. And I love it.

As far as I’m concerned, the more ‘cheap’ product that comes into the market the better. It just introduces more people to what’s out there, and people aspire to having quality.

CH: One aspect of the Rode sound that this magazine has had a recurring quibble with is the tendency to accentuate sibilance. Is that a criticism that you’ve looked into?

PF: Rode microphones have a sound… and it’s why our customers buy the mics! But that sound doesn’t suit everyone or everything. You should hear some of the studio sessions I’ve been to. You sit back and you think ‘that’s as good a sound as I’ve ever heard’, and you find out it was one of my NT1000s or something. Then a certain style of female vocalist may sing into it – and ouch, it’s not the right mic.

Another example: a lot of well known black rappers in The States love the old Classic and the NTV. If you’ve got a really deep ballsy voice, I’ve not heard better. For some string instruments, nah, I don’t like it so much. A super-sibilant girl’s voice… I don’t like it. No mic manufacturer would suggest their designs are great on everything, and we’re no different.

So, yeah, we have our sound, and I don’t have the nuts to stop making a flavour that a lot of people love. I’m making Jack Daniels and you’re telling me that a lot of people don’t like Jack Daniels. Okay, that’s fine. But rather than change my Jack Daniels recipe I’d rather start another little thing on the side and make single malt whisky.

CH: You’re referring to the new HF1 capsule, as found in the NT2000 and K2?

PF: I’ve changed the sound of that capsule to make the NT2000 and K2 sound much more like what people refer to as the ultimate references. Sonic flavours such as the Neumann U47 and AKG C12 are definitely bench marks.

CH: But obviously they’re mics with track records that date back decades. It’s a very brave reviewer or studio pro that goes out on a limb and says, ‘forget about the $20,000 mic because the $2,000 K2 is better’. Unless the newcomer is cloned on a subatomic level there will be differences.

PF: Sure, I guess all I’m getting at is that I’m not just in this game for the money. I love music. I love great audio design. And I love making things. I think Rode is writing its own history and in the end I’m after the ultimate accolades. I’m a bit like a muso who wants to be on the top of the charts. I want the company to become one of the all-time legends.

CH: The problem with legend status is that it generally comes posthumously…

PF: So I guess it’ll have to wait… I’m not planning on dying any time soon!

RESPONSES