Most Important Linkin The Chain?

High profile mix engineers like Manny Marroquin are employed for their magic touch, but does it stand up in a blind listening test? Linkin Park put it to the test for their latest record Living Things with a good old fashioned mix shootout.

At the start of this year Manny Marroquin received an unusual request. Would he be prepared to mix two tracks for a forthcoming Linkin Park album in a mix-off against other top mixers? The band, producer Rick Rubin, and Warner Brothers chairman Rob Cavallo were to listen to these mixes blind on CDs simply marked A, B, C, etc. The winner would take home the job of mixing the rest of the album, and those that lost would get, well, nothing. It may sound like a straightforward case of ‘may the best mixer win,’ but the fact of the matter was that all the approached mixers were the best in their field, had nothing to prove, and not a day to lose in their already jam-packed schedules. Nonetheless, 10 mixers took on the challenge.

Marroquin was the eventual winner, which is arguably an unexpected result. He’s more known for pop and hip-hop/R&B mixes than for working with heavy walls of electric guitars. Marroquin’s credits include Alicia Keys, Bruno Mars, Lana Del Rey, Usher, Cee Lo, Pitbull, Rihanna, Flo Rida, Justin Bieber, Kanye West, Christina Aguilera, and many others. You get the idea.

“In recent years I’ve actually mixed music from more and more genres — from rock, to folk, and even country. And the music on [the album] Living Things is very diverse, incorporating anything from indie punk, alternative rock, hip-hop, and electronica, to country,” said Marroquin. “The two songs we all mixed during the shoot-out were Burn It Down and Lost In The Echo, which became the first two singles. I’m sure that what the other guys did was great, but they may have been more focused on one genre, whereas I felt I was able to work with and combine all the different influences. Luckily I got the call to do the album, which turned out to be a great experience. They’re really cool guys that know what they want, and they gave me space to do my own thing as well, which was really refreshing.”

THE TALE OF TWO MIXES

The tale behind Living Things reflects many of the issues that affect the music industry in 2012. The overriding concern is, of course, the continuing downward sales spiral. A quick check of the album sales of virtually every major act that’s been around for a while shows a steady and sometimes dramatic decline. Linkin Park is typical: according to Wikipedia the band’s debut album Hybrid Theory (2000) sold 24 million worldwide; the follow-up Meteora (2003) sold 16 million (even though it reached higher up the charts than its predecessor); next up was Minutes to Midnight (2007) with 8 million sales, again despite it reaching No. 1 virtually everywhere; and the fourth album, A Thousand Suns (2010), sold ‘only’ 1.7 million, while enjoying No. 1 spots in the US, Australia, Germany, Japan, the UK and elsewhere.

These figures are staggering and, given they’re pretty universal, are a clear indication of the crisis that’s engulfed the music industry, rather than a sign of decreasing popularity of Linkin Park. With a relatively throwaway consumer approach to music that’s focused on trillions of single tracks available at the click of a button, parking at the top spot is harder than ever. One of the silver linings behind this huge dark cloud is that what technology taketh away, it also giveth, and the arrival of the DAW has made it possible to record music at a fraction of what it cost in the past. While this sadly has decimated the studio industry, it also continues to be a godsend for those recording on a budget, which is virtually everyone these days. In this scenario, the role of the mixer has become increasingly important, to the point that the music industry now has a number of star mixers with clout and a reputation that’s akin to that of big-name producers. When attempting to make records that stick out from the crowd, the fairy dust that mixers can sprinkle over music is increasingly highly valued — hence the mix shootout for Living Things.

IN DEMAND

But with this elevated importance, comes a natural supply and demand conundrum. The Grammy-winning engineer arrived as one of the US’s top mixers in 2000, following his work on the debut albums by Pink (Can’t Take Me Home) and particularly Alicia Keys (the best-selling Songs In A Minor). He’s since gone from strength to strength and in recent years the demand for his services has risen to a staggering degree, putting him in a position where he often works six days a week, for 16 hours a day or more. As a result, the interview from which this article is culled was conducted in several shorts sessions of 15 to 30 minutes each, whenever he managed to find breaks during his mix sessions — sometimes at 3am!

Even amongst the mix shootouts and long working days, dealing with high profile artists can still carry some surprisingly odd additional baggage. Regular Lil Wayne mixer Fabian Marasciullo once told this writer how, when mixing the rapper’s Tha Carter IV in 2011, he was carrying the hard drives with him all the time, as well as a gun whenever he went out on the Miami streets! When Marroquin began mixing Living Things, he was suddenly faced with similar security concerns. “Things got off to a shaky start,” he said. “Security guards brought the drive each morning, insisted on being present in my mix room for the day, and took the drives with them again in the evening. I don’t like people who I don’t know being in my studio, so I nearly pulled out because of this. However, the security guys turned out to be cool and really ‘got’ what I was doing, so there soon was a good atmosphere. Eventually they waited in the lounge at Larrabee [studio] rather than being in the room with me all the time.”

SUPER ANALOGUE

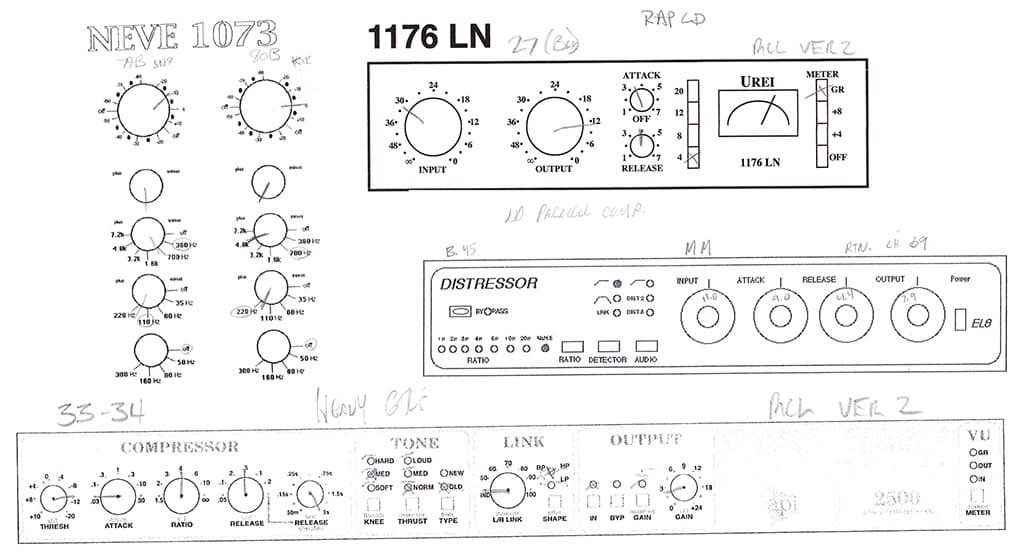

Marroquin is a creature of expensive habit. After 14 years at Larrabee Studio 2, he still works with the same analogue-digital hybrid that he’s always favoured. His choice pieces of hardware continue to be a huge, 80-input SSL XL ‘K’ 9000 series Super Analogue console, and compressors by API, dbx, Drawmer, Empirical Labs, Manley, Neve, Teletronix, TubeTech and Urei; EQs by API, Avalon, GML, Millennia, Motown and Pultec; and reverbs by AMS, Eventide, Lexicon and TC Electronic. He prides himself in combining these old-fashioned goodies with the best that ProTools has to offer. It’s an approach that allows Marroquin to work with a wide variety of artists and musical styles.

“In the past I was more geared towards mixing pop, but now I may be mixing John Mayer one day, and the next day it could be Justin Bieber,” said Marroquin. “So I pay more attention to the style of music that I mix, the vibe of each song, and what kind of audience it will appeal to. If it’s a John Mayer project that doesn’t have to be super-limited and radio friendly, I’ll use more outboard and get more of a sense of width, depth and warmth. If a very pop-sounding mix is required, I may not want to warm it up and squeeze it some more, using more plug-ins and a limiter like the Waves L1. Digital brings its own excitement. Sometimes pop mixes require an in-your-face crunched sound rather than a lot of depth. But I will never mix something completely in the box.

“When I first started working in this room, there was an SSL G-series, and then we had a J, and seven years ago we moved to the K. It sounds great, with a nice punch, and it’s very versatile. After 20 years in the business, 90 percent of the time I still monitor through my Yamaha NS10s with Bryston amplifiers. I also have Augspurger main monitors, and once in a while I listen to my KRK E8s, which are like desktop speakers. The SSL is my main mix tool. Every single thing I do goes through the desk. I may be old school in that I prefer to mix on a desk, but I also use a hybrid of analogue outboard and digital software. This means that about half of my effects come from software and the other half from hardware. Although plug-ins have become better over the last three years, I still find the sound lacks depth when it remains in the box. So I continue laying things out on my SSL, which has wonderfully smooth top end and an amazing low end.

DEFINING A SOUND

Marroquin mixed the entire Linkin Park project at his room in Larrabee Studios, including the two songs that he mixed for the shoot-out. “My approach was pretty much to imagine how I, as a music fan, would like to hear Linkin Park in 2012,” he recalled. “I can’t reinvent them or give them a different sound, but I felt that in 2012 they needed an aggressive sound with balls, with a very modern-sounding rhythm section. I didn’t want it to be a hip-hop rhythm section, but I also didn’t want it to sound like straight-up rock. There had to be aggression in the drums, bass and vocal, and presence in the overall sound image. I always put a lot of emphasis on the vocals, in this case Chester [Bennington] and Mike [Shinoda]. It was always about them, the rhythm section and the wall of guitars.

“I wasn’t given any brief for the shoot-out, but afterwards I met the guys, and we spent some more time on Burn It Down, because it was going to be the single. They’d also made small changes to the arrangement after I first mixed it. My initial mix had taken a couple of days, and I recalled it and did some revisions. I had the band, Rick Rubin and Rob Cavallo — all pretty strong personalities — in the room at the same time. If I’d really thought about it, it would have been a little intimidating! Doing that song took the longest, as we all wanted to make sure it was radio-friendly, and that the sound and vibe were right. That was a collective effort, and the aim was to mix it with big choruses, and bring out the rhythm section, which almost has a dance feel to it. One thing that we also worked on together were the dynamics, making sure the choruses jumped out at you when they came in.

“In some ways this song provided a blueprint for the album, but at the same time the approach was for every song to have its own identity. There’s a song called Victimise, which is really raw and hard, a song called Powerless that’s almost like a power ballad, and a song called Castle Of Glass that has a folk melody. The idea was to give each song its own space, and then the challenge was to connect all the dots and make sure the album as a whole was cohesive, because it’s easy to mix 10 completely different-sounding songs.”

Digital brings its own excitement. Sometimes pop mixes require an in-your-face crunched sound rather than a lot of depth. But I will never mix something completely in the box.

WHERE TO BEGIN

Moving on to the specifics of his approach to mixing in general and his mix of Burn It Down in particular, Marroquin explains, “I always start a mix by working on the drums, even if there are no drums in the session. What I mean is that I always start with getting the groove right. Once I have the groove, everything else becomes a little easier. Then I’ll bring in the bass, which in this song is a synth bass. Once I’m happy with the groove, I’ll bring in the vocals to make sure they feel good against the drums. I may not EQ the vocals or look in great detail at them, but I’ll make sure the vibe is the way I like it. After that I’ll add the guitars and then the keyboards, and once I have them sorted, I bring the vocals back in. At this point I focus on the choruses, I really want them to explode. I loop the choruses and make sure they feel as big as possible, using EQ, compression, levels, and so on. After that I work on the verses as well, and make sure they sit in the right place relative to the choruses.

“I always listen to a rough mix when I start work on a session, preferably right before I begin mixing a song. This usually gives me a pretty good idea of where the artist and producer want to go. The session will normally sound more or less like the rough mix, with levels and plug-ins that were used in place, and I’ll first play with the levels and plug-ins that I’ve been given. I listen for things I want to change and I start tweaking. Everybody has the same plug-ins, so they are of good enough quality sonically, and if somebody adds EQ or an effect I take that as part of the production. In short, I start with what I’m given, and then build from there. I’ll generally tweak every single plug-in that was already on the session, and add others that I think are necessary, and I’ll then move on to the outboard. I’m super fast with my outboard because it’s hardwired into my desk, in fact, faster than with plug-ins. If I want to apply outboard reverb, I know where it is and only have to press one button to activate it. Opening a plug-in and waiting for it to load and then applying it to a track and varying its parameters often takes longer!

DRUMS & BASS

“The drums on Burn It Down consist of three loops, two kicks, a snare, three hi-hats, overheads and five crash tracks. There are many instances of the Digidesign EQ [EQ1B, EQ4B, etc], which Mike Shinoda put there — he loves the Digi EQ. There’s also the Avid Focusrite D3 compressor/limiter on Loop 1, kik2, and the snare that were already on the session. Mike also put the Lo-Fi on the snare — he loves that too. The snare was the most challenging aspect of the drums to mix. It was a very interesting snare sound, but it had to sound dirtier, hence the Lo-Fi. Two of the crash tracks have the Waves PS22 widener on them and there’s also a Waves L2 on one to add some rock crunch. The outboard was an Avalon 2044 compressor going into a Neve 1073 EQ on the kick and the snare, which came up on Channels 4, 5, & 6 on the board. I also added parallel compression on all the drums, using the Neve 33690 compressor and the Pultec EPQ-1A, to add more punch. The [Thermionic] Culture Vulture was automated to become active in the choruses on all the drums and the bass. In the section where Mike raps, the rhythm section completely changes. It goes to an entirely different loop and I again wanted to make sure that the rhythm was tight and secure. One of the biggest challenges was making sure these different sections all tie together. As for the bass, an [Access] Indigo synth provides the bass track, and it has a Sansamp plug-in and a Digi EQ, plus the 33690/Pultec chain I mentioned above.”

GUITARS & KEYBOARDS

“The guitars and keyboards were more or less treated as one unit. There was no great distinction in working with them. Several of the tracks were sent to the same outboard to provide a bit of glue. A Roland Gaia [‘2.02.1’ on the Mixer view] is the hook synth you hear right at the beginning. I call that a focal point, and for me these are easy to mix in. Once the rhythm is perfect, you can always add focal points, because their character will shine through. Rob Cavallo in particular wanted to make sure this synth hook sounded right, and we ended up adding some distortion to it, to make sure it had more of a progressive dance rock flavour. I used only outboard on it, in particular the Fairchild compressor, and a bit of reverb, as well as my Strymon Brigadier delay pedal, which is really cool. The main synths are all going to the Fairchild, and the Gaia synths had parallel compression from the Retro Sta-Level. There’s also an API 2500 compressor on the heavy guitars. Most synth and guitar tracks also had SSL desk compression and EQ.

“On the plug-in front there are, again, several instances of the Digi EQ, plus the DVerb on the second Gaia synth [Gaia 02.1 on the Mixer view], the MetaFlanger and Focusrite D2 on the electric piano, a D-Verb on one electric guitar and there were delays from the EchoFarm on two of the synth sounds. There are also three noise loops, that all came up on Channels 41&42 on the board; but you can barely hear them in the track. One of them has the Lo-Fi, two of them have the Digi EQ and all three have the PS22 Widener. Finally, there are the Hook Key Stabs, which came up on Channels 43&44, that had the Focusrite D3 plug-in and a Digi EQ plus a reverb, and five Sound FX tracks, which had quite a few plug-ins on them. It’s all just vibey stuff that in general needed lots of delays and reverbs, coming from the MetaFlanger, Air Reverb, SansAmp, EchoFarm and D-Verb. All sound effects channels came up on Channels 45&46 on the board.”

DRAWING OUT CHESTER’S VOCALS

“There are two leads vocals, Chester’s, which consisted of two ProTools tracks that both came up on desk Channel 27, and Mike’s, which was on one ProTools track that came up on Channel 28. Chester’s backing vocals were on 31-34 and Mike’s doubles at 29&30. Chester’s vocals have the Digi EQ and Medium Delay, as well as the Waves R Compressor. On the board my signal chain on his voice was the TubeTech CL1B EQ going into the Avalon 2055 compressor and then the dbx 902 de-esser. I also applied a lot of parallel compression with the Distressor on the vocals, sometimes using a Urei 1176. There were similar effects on Mike’s vocals. I also printed Chester’s lead vocals to an Ampex ATR-102 with one-inch tape for a tape delay effect, and brought it back into the session, which is why it has the Time Delay plug-in on it. In addition, I have the Brigadier pedal on some backing vocals, and I set up a reverb and two delay effect tracks in ProTools, using the Reverb One and Waves Super Tap delay. I had these effects mainly on the vocals.

“The rest was SSL EQ and compression, and also the AMS DMX15-80S as a harmoniser and the AMS RMX16 and Lexicon 480L for reverb, plus the Lexicon PCM42 for delays. By the way, I also used an SSL side-chain as a de-esser. The dbx 902 is great, but it only takes away one frequency. On the board I can create a side-chain that also grabs other frequencies. It’s the best-sounding de-essing process I know of and it’s based on an old trick that I picked up from engineer Barney Perkins. I route the vocal signal to two separate channels on the SSL right next to each other. The first channel is my side-chain and the second channel is my actual vocal channel. On Channel 1 I’ll set the SSL compressor to a fast attack and I’ll also engage a high-pass filter and do extreme EQ-ing of whatever frequencies I want to remove. But I don’t cut these frequencies, instead I boost them +12dB with a very narrow bandwidth. They are most often around 6-7kHz, where most of the ‘esses’ happen. So Channel 1 accentuates what I’m trying to take away! I take this channel off the stereo bus, so you won’t hear it in the mix.

“I then press the Link button to link channel one to Channel 2 and I engage the compressor on Channel 2. What happens is that the more I’m bringing up Channel 1, the more the compressor on Channel 2 ducks the frequencies I don’t want on that channel. My Channel 1 fader is in effect my threshold. This is why I’ve taken out the bass frequencies on Channel 1, because I don’t want them to disappear in Channel 2. But with side-chaining, the frequencies you’re accentuating in your side-chain are ducked in the other channel. People find this technique hard to understand; even the people at SSL don’t quite understand why it works! But it does. If you’d try to simply EQ to remove your ‘esses’ you’d take all the life and presence out of the vocal. But de-essing with this technique retains the personality of the singer. Finally, I put an Avid Impact limiter on the stereo mix, I used the SSL compressor on the board, and also had the Hybrid Brainworx was my EQ on the stereo bus.”

QUALITY WINS OUT IN THE END?

Whether the mix shoot-out and the added value from Marroquin’s mix work and ‘bang!’ effect will translate into significantly increased commercial success for Living Things remains to be seen, but so far the signs are good, with the album having reached the top spot in well over a dozen countries, including the US, the UK, New Zealand and Germany, and a No. 2 placing in another dozen nations, amongst them Australia, France, and Japan.

RESPONSES