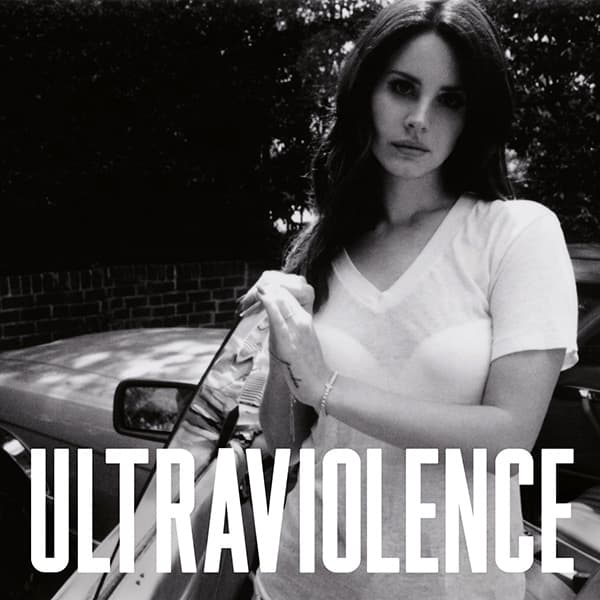

Mix Masters: Robert Orton on Lana del Rey’s Ultraviolence

Lana del Rey’s metamorphosis continues, but mixer Robert Orton assures the image is all of her own making. Orton mixed her latest hit record Ultraviolence completely in-the-box, and he wouldn’t do it any other way.

Artist: Lana del Rey

Album: Ultraviolence (2014)

It surely must count as one of the most impressive artistic reinventions of modern times. In 2010, Lizzy Grant was flailing around in obscurity, having released an EP called Kill Kill and an album, Lana del Rey, that both flopped. A year later she had undergone a radical image make-over, as part of which she adopted the title of her debut album as her artist name, and released a debut single called Video Games that was taking the world by storm. Despite the song and video being widely lauded as atmospheric masterpieces, there was a lot of scepticism about the depth of her artistic authenticity and speculation she’d prove to be little more than a one-hit wonder. When her subsequent album, Born To Die also proved extremely successful, the sceptics moved the goal posts and declared del Rey a one-album wonder.

Then del Rey released Young and Beautiful, the pinnacle of her maximalist aesthetic, and perfectly suited to the excess of Baz Luhrmann’s take on The Great Gatsby. It was followed by del Rey’s own stab at filmmaking, Tropico, a veritable mini-epic in the scheme of music videos. But just as her star looked poised to settle on this impeccably-crafted horizon of grandiosity, del Rey has sidestepped her critics once more.

Her third album, Ultraviolence still features the mournful atmospheric pop del Rey made her mark with on Born To Die, but replaces the bombastic orchestral elements with a more limited and focused palette of alt-rock tremolo guitars, reverb-swamped vocals and drums, and trip-hop influences. It’s Lana stripped back, yet Ultraviolence still topped the charts the world over.

The album’s making featured a proliferation of heavyweight producers: The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach, Paul Epworth (Adele), Rick Nowels (Madonna), and Greg Kurstin (Lily Allen). But despite the share of influence the album as a whole is remarkably cohesive, suggesting del Rey was pulling the strings and further evidence she’s not the manufactured starlet her sceptics initially assumed.

This impression is confirmed by Ultraviolence’s principal mixer, Robert Orton, who mixed 10 of the 15 tracks, if you count the bonus tracks on various deluxe editions. Orton recalls that all 10 tracks were “mixed pretty much in one go, because Lana wanted to be present throughout the mixing. So the timing was dictated by her schedule. It was great having her in the room, because she had such a clear vision of how she wanted the record to sound. Lana is very articulate and has great ears, so it was wonderful to get instant feedback as we tried out different ideas. It also meant there were very few recalls to deal with.”

HOT HANDS

Orton mixes out of his own room at Hot Rocks Studios in Los Angeles, where he moved about three years ago from his native London. The mixer started playing piano at age five, and as a young adult went to the London College of Music in Ealing in West London, where he graduated in Music Technology & Media Technology. Two big breaks followed soon afterwards. In 2000 he started work as ProTools engineer for Trevor Horn, and two years later he ended up with engineering, mixing and additional production credits on the first western album by t.A.T.u., 200km/h in the Wrong Lane, which became a major international hit. Orton worked with Horn until 2008, amassing credits with Pet Shop Boys, Seal, Lisa Stansfield, Elton John, Texas, Celine Dion, Kelly Rowland and Macy Gray. Since going independent six years ago, Orton has quickly established himself as one of the world’s leading hit mixers, mixing songs and albums for the likes of Lady Gaga, Carly Rae Jepsen, Emeli Sandé, The Police, Flo Rida, Sean Kingston, Kelis, Ellie Goulding, Mary J Blige, Usher, and Robbie Williams, which led to him earning three Grammy Awards.

Orton is part of a new generation of hit mixers, and it comes as little surprise he wholeheartedly embraces the latest in digital technology. Particularly, he prefers to mix in-the-box. “I think the quality of mixing in-the-box is every bit as good as mixing on a board,” he asserts. “You may get a slightly different sound, but it’s certainly not worse. I actually feel I get a slightly more up-front sound from mixing in-the-box. Some people complain they don’t get the same air, but I find you can get perfectly airy mixes with HD audio and today’s plug-ins. Overall, I don’t think it’s that important whether you mix in-the-box or on a board. What’s far more important is finding a way to articulate the message in the music using whatever tools you’ve cut your teeth on.

“I have a few pieces of hardware in my rack, such as some Empirical Labs Distressors, but I don’t find myself reaching for them too often. There’s been an explosion of plug-ins modelling classic hardware in recent years, and as the technology has improved, so have the models. I’m a big fan of many of the UAD plug-ins because they sound so great. There have been plenty of attempts in the past at modelling the classic Fairchild 670, but the new UAD Fairchild is the first one that really made me sit up and think, ‘wow, this thing actually sounds like a Fairchild.’ Not only that, but you can have dozens of them in your session. Mixing in-the-box is the only way that makes sense to me, especially when you add in the flexibility it gives you with recalls.”

It was great having her in the room, because she had such a clear vision of how she wanted the record to sound

BOX OF TRICKS

Even a totally in-the-box studio needs some hardware to function. Elaborating on the most important bits of hardware in his studio, Orton explains, “The room I work in is really important to me because I need to know I can trust what I’m hearing from the speakers. Not only that, but it’s important to be able to work in a comfortable environment because I spend most of my life there. My room here also has a nicely-sized tracking room, which is a useful thing to have access to. The acoustic treatment of the room, which was designed by John Edwards, is one of the most important things to me because I can trust what I’m hearing and it helps with making correct decisions. If you’re not hearing what you think you’re hearing, you have to work twice as hard and the mix will never turn out as well as it could.

“With a ProTools rig and an acoustically correct room you can achieve anything you want if you know what you’re doing. Much of the gear I have is focused on achieving clarity in what I’m hearing: I have a variety of monitors I like to listen on, and Prism AD/DA converters which I love for their punch. My main monitors are soffit-mounted Ausperger speakers with TAD components. I also have some midfield Quested VS2108 monitors that I spend a lot of time listening on. Some of my favourite speakers are made by Quested. Roger is a wonderful speaker designer and I love his monitors for their incredible clarity and detail. I also have Yamaha NS10s and ProAc Studio 100s — although I don’t usually have both up at the same time. ProAcs make a pleasant change when I get tired of the very forward mids of the NS10s. Another important aspect of my monitoring setup is my Crookwood monitor controller, which is super clean and transparent. All these things together help me feel entirely confident I’m hearing exactly what I should be hearing, without coloration. Finally, I’m not a big fan of clocks or summing boxes, although I can see a case for the latter if you’re specifically looking for it to colour the mix a certain way.”

Positioned at the crest of a wave of young, contemporary mixers Orton operates not only at the cutting edge of modern technology, but also has a fresh and different perspective on the perils of today’s fast-turnaround, low budget studio industry. Many mixers with roots in the big-budget analogue days complain they’re increasingly competing with rough mixes, which not only tend to be exceptionally loud (meaning they have to come in as loud, if not, louder), but more sophisticated than ever, because producers and tracking engineers also have all the mixing tools available to them. These mixers feel their creative leeway is continually reduced, to the point one big name mixer told this writer he feels all he does in many cases is just “bless the rough mix.”

Orton has a very different perspective: “It’s true to say rough mixes have become more sophisticated, but I don’t agree it places a limit on my creativity. If you’re not in competition with a great rough mix, then you can just as easily be in competition with another mixer. Just because everyone loves a rough mix doesn’t mean you can’t bring something new and exciting to the record, it just means you have to pay careful attention not to spoil the hard work already put into making the record. That often means you have to work harder, but the end result is usually a better record. Having said that, it’s nice when a client isn’t too tied to the rough mix. It’s liberating when you have complete creative freedom.

“I do agree that the lines between tracking, mixing and mastering are more blurred than they’ve ever been. As a mixer, my work is often being compared to released material, which has of course already been mastered, so it’s important my mixes stand up to that. I routinely use various mastering tools (EQs, limiters, etc) to make the mix sound as close to the finished product as possible. That doesn’t necessarily mean making the mix as loud as possible, although some clients do want that, but it’s about getting every last bit out of the mix. Making a record is a collaborative process, and just as the artist, producer or engineer might speak to me during the process of a mix, I’ll sometimes speak to the mastering engineer too.”

ROUTINE RECALLS

Given that Orton has worked in-the-box for most of his career, there have been very few changes in his working methods as digital technology has progressed. “My working methods have remained the same for several years now,” he elaborates. “I probably place more emphasis on laying out a session exactly how I want before starting a mix than I did in the past. That’s out of necessity because of the high volume of work I have. If you get everything organised well before you start the mix, you’re able to spend more time focussed on the things that matter, which makes for a better mix. My usual routine involves starting around noon, unless there are pressing recalls to take care of, in which case I’ll start earlier. The session I’m working on will already be prepped so I just pull it up and start listening.

“I familiarise myself with the song by listening to the rough mix a few times and placing markers in the session to help me understand the structure. Then I start working on the mix and keep going until it’s finished. Sometimes it doesn’t take long, often I work late into the night, but I usually finish a mix a day. If I work late, I like to listen to the mix the following morning, because it can be helpful to listen with fresh ears and a clear perspective. Maybe I’ll change one or two things and then print before moving onto the next mix. I don’t have a set routine for tackling recalls. When I receive recall requests, I sometimes work on them after I’ve finished the day’s mix because I don’t want to spoil the flow I’m in. Other times I might like a break from what I’m working on, so I work on a recall as I receive the comments. Being able to swap between songs quickly and easily is certainly one of the huge advantages of mixing in-the-box.

“There wasn’t much jumping between songs when I mixed Lana’s album. Generally she and I would work on a mix until it felt right, then we’d listen to the mix in the car. Sometimes we’d go back into the studio for a few more changes and sometimes we’d pull up the session the following day, but usually when it sounded right in the car we knew the mix was finished. The two main singles from Ultraviolence that I mixed, Brooklyn Baby and Shades of Cool, were done this way.”

RESPONSES