Mix Masters: Mixing From Stereo To Dolby Atmos

Mix Engineer, Tristan Hoogland, kits himself out for Dolby Atmos Music mixing, and breaks down for us what he learnt along the way.

Artist: Felivand

Album: Ties

As technology evolves and the new Dolby Atmos format gathers momentum, the expectations of mix engineers only multiply. In-demand mixer and Aussie expat, Tristan Hoogland, has risen to this new challenge and reaped the rewards. He talks to AudioTechnology’s Greg Walker about his decision to set up Atmos mixing in his own studio and shares his experience mixing the new Felivand album. Get ready for a bunch of valuable insights into working with the format and the techniques Tristan has learnt from hard-won experience.

TAKING THE PLUNGE

AT: You’ve mixed a lot of records in stereo. At what point did you decide you needed to take the plunge and get your own Atmos setup in your studio?

Tristan Hoogland: Initially, for Atmos mixing, I was working out of a studio called Electric Ear, which is run by a friend of mine, Gideon Zaretsky. It’s a beautiful studio: big console, lots of great outboard gear and the Meyer Blue Horn monitors that film people really love. I would rent it once a week or so, because it was still fairly early days for the format. Maybe one out of every 30 songs would get an Atmos mix requested. Then, gradually, the pace started picking up. After about nine months of sporadically renting Gideon’s studio I had two records come in where they said ‘We need them both in Atmos’.

My manager thought it was probably the right time to jump into setting myself up for Atmos. To be honest, I didn’t really want to spend the money. The challenge of setting up a studio in general is already a headache, let alone working out how to throw another 11 speakers and a sub into a space. That said, it didn’t feel smart to pay rent on an Atmos mix room on top of the rent for my own studio. So, finally, after a lot of research, I decided to invest in Genelec’s SAM system.

There are lots of costs getting into Atmos. The extra speakers, that’s one thing, but then how do you control the volumes for all of them? Getting a monitor control like the Grace surround sound box costs something like US$8000. That’s just for the monitor controller!

My instinct told me not to spend that kind of money on a format that still feels a bit speculative. Atmos was definitely having a moment, but I didn’t really know what the future of it would be. I eventually took the plunge and invested in the Genelec system, in no small part because of the $100 volume controller knob they launched as a companion product. Then I upgraded to an Apogee Symphony so I could get the 16 channels I needed. To my mind that was the most affordable, yet the most professional, solution.

MAINTAINING THE GLUE

AT: So with a project like the Felivand album where you’ve already done stereo mixes, what’s the process? How do you deconstruct your stereo mix and create the Atmos one?

TH: The way I work with Atmos mixing has evolved. Many people tend to base their Atmos mixes off the discrete stems printed from the final stereo mixes. So you start a fresh session and then you import individual mixed stems, which contain all the mix bus processing. Then for the most part you’re playing with just panning those stem elements around the room as you see fit.

Initially, that was my approach but after about six months I realised the one thing that I was always struggling with was getting the key elements of the mix to glue together. The reason for that, is when you play those back in Atmos, they’re more open because elements like the drums and bass aren’t getting processed together by whatever’s on the mix bus, such as compressors, saturators etc.

I really wanted to solve this problem for myself. How do I maintain the ‘glued’ sound but have the flexibility to pan certain elements around?

AT: What was your answer?

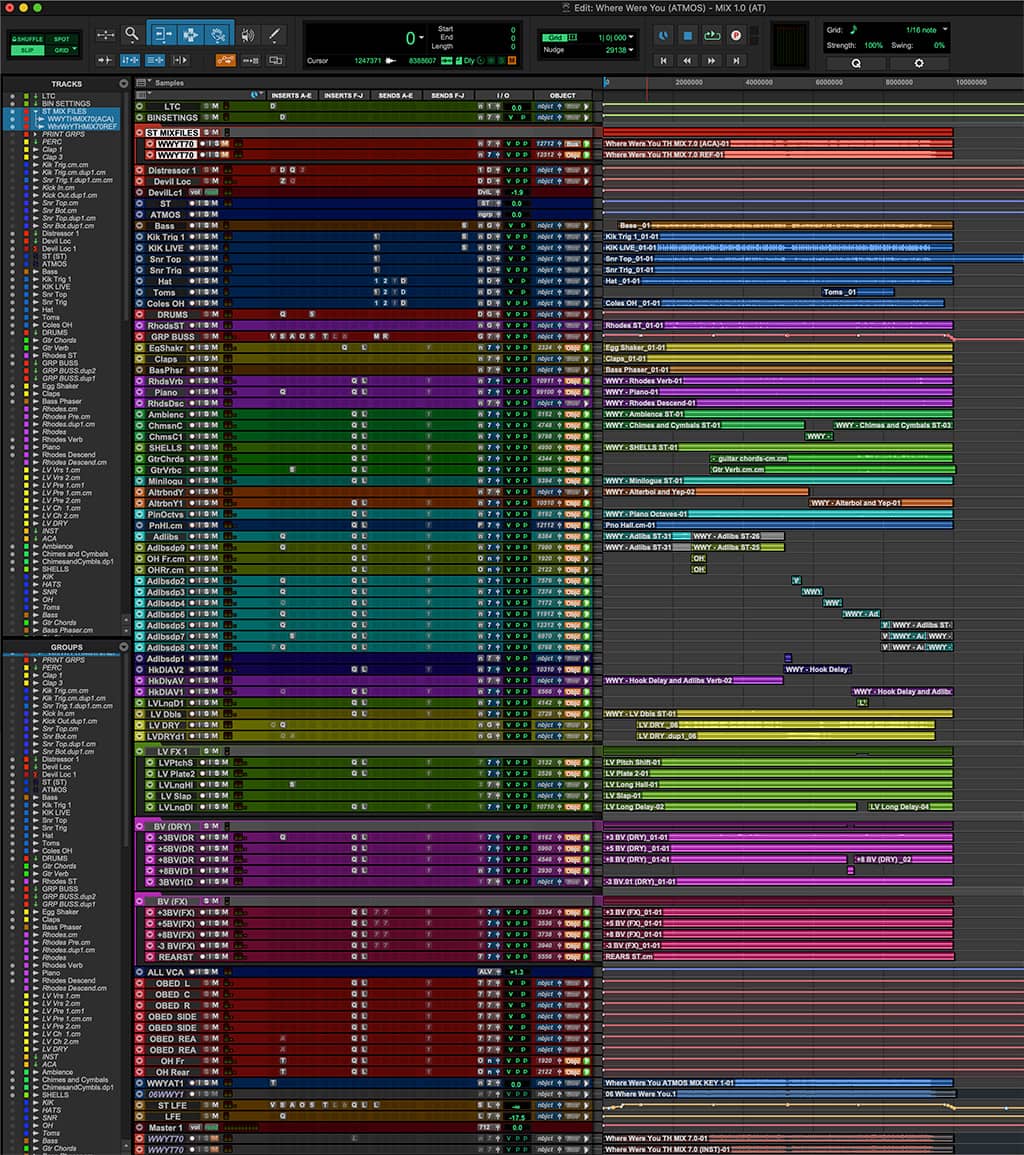

TH: My assistant Hamish Patrick and I worked pretty hard at this and we found another approach in Pro Tools. This is the real benefit of working entirely in the box: we could import the entire stereo session to the top half of a brand new session and then import all the mixed stems to the bottom half. This meant I could start with the stereo mix in the front speakers and then take something like a synth part, mute it in the stereo mix part of the session and unmute it in the stems section and move the synth out into the room.

Usually what I found would happen is that the majority of the power of the mix needed to come from the left/right front speakers. Those principal, strong and transient-heavy, left and the right sounds are usually the drums, bass, maybe a guitar or something, and definitely the vocal. Those three things in particular. Coincidentally, those three things (drums, bass and vocals) tend to always be the things that drive the mix buss the hardest. So I could mute 80% of the stereo mix and just keep the drums, bass and vocals in there and still feel like I had the energy of the buss processing keeping the mix glued together.

AT: Right, so you keep the bedrock of drums, bass, and vocals then work up and outwards from there.

TH: That’s right. With those key elements in place, I had the freedom to play with all the other more atmospheric elements — the Felivand record has plenty of those. Atmos mixing lends itself to that stuff really nicely. At some points there might be four or five reverbs that I can carefully place in the room.

Typically I might leave the vocal completely dry in the front speakers, but then I’ll have the shorter room reverbs slightly back. Then as the space goes further back behind me, I might have a plate reverb there, and the hall reverb at the very back.

Working like this really helped unlock things for me. Rather than just doing the individual stems, with it feeling a little less glued together, I felt like I could maintain the integrity of the stereo mix and the energy of the bass slamming with the drums and the vocal and any other key elements, but I got all the benefits of the spatial stuff when I needed to. So that’s one of my key learnings.

Another benefit of working like this is that I’ve already made all my EQ and compression decisions in the stereo mix. I didn’t need to buy a big Atmos system because I’m mixing on larger ATC SCM50s for the stereo mixes. I can rely on those monitors and I know I’ve made the right tonal and compression decisions. Then I’m mainly using the other speakers for the panning. I might add some reverbs and other creative atmospheres, but for the most part I’m moving things around and using the space.

AT: There are many benefits to having the same mixer do the Atmos mix as opposed to someone else taking over and rebuilding it.

TH: Yeah, exactly. For me it’s less about being precious about my stereo mix, but more that I already know if an artist is going to want more reverb on their vocal. I know because I’ve already gone through the revisions on the stereo mix whether they’re ambitious enough to have everything mixed at the back of the room. That part makes it invaluable. I heard a lot of stories of it going to other people and there would be a lot of revisions. For me, to this point, I’ve only had one revision on an Atmos mix. I don’t do these mixes for other people’s projects. That wasn’t the reason I got into it. I just wanted to do it on my own mixes. I can make calls on things that I know everyone will be happy with and I won’t be in ‘revision land’ forever.

I could maintain the integrity of the stereo mix and the energy of the bass slamming with the drums and the vocal and any other key elements, but I got all the benefits of the spatial stuff when I needed to.

MIXING AT SCALE

AT: What’s the hardest part of Atmos mixing?

TH: The best, but trickiest aspect of Atmos, is that the format is scalable. So the idea is that if I mix in 7.1.4 it can get played back in a 9.2.4 room, or a 5.1 room or a 2.0 room or headphones (which is known more formally as binaural). The idea is you have one mix and it will algorithmically up-mix or down-mix, while doing its best to maintain relative positions and balances made in the original layout. In surround sound, it was a specific speaker setup, whereas Atmos is really an algorithmic fold-down, fold-up thing, unlike when you did the big cinema mix, then you did the 5.1 mix, then the stereo mix for good measure. You don’t have to do that anymore and I think that’s where things get interesting.

Pulling a good sound in the room isn’t hard, but folding down to the headphones is really the challenging part, in my opinion. Getting it to really translate in the headphones is quite tricky because the idea with the binaural is that it’s trying to emulate the experience you get in a speaker environment. The algorithm gets updated and is always being improved but there are certain things about it that are harder to balance against the speakers.

AT: So the binaural is a set of Dolby algorithms?

TH: Yeah. So this is a Dolby thing and all the depth and placement parameters have a bit of a sound to them as well. When I first started mixing Atmos I couldn’t really hear it in the headphones. Now I can hear it pretty well, but getting those settings right took a while. I would say I spend 60-70% in headphones to get them right. I get it working really well in the speakers and then I’m constantly going between the headphones and the Airpod Maxes which do all the spatial audio stuff too. I check on those as well because that’s the way a lot of people are consuming Atmos. If they have Apple Music it’s likely they’ll have a pair of headphones equipped with it.

AT: It sounds tweaky.

TH: It’s a very technical format at the moment. The workflow isn’t straightforward but getting easier as enhancements flow through. We’re all accustomed to checking a stereo mix in the car, then taking what you heard back into the studio for some tweaks. Often you might reach an impasse: ‘do I make it sound better in the car or the studio?’. You’re constantly straddling that line. What’s the compromise here? In the same way, I’ve had Atmos sound amazing in the speakers, and then I put the headphones on and certain elements really pop out in the binaural mix — ‘Wow, who put reverb on the whole mix?!’. So it’s a bit of a compromise at the moment.

AT: What’s your approach to quality control with the artist?

TH: With Felivand, she’s in Australia and I’m in my studio in LA. She can’t come into my studio and listen to the atmospherics. She would have to rent out a room in Australia and that costs money. And so the headphone thing is really important because she can listen to renders of the binaural versions.

On Apple Music you currently toggle Atmos on or off. It’s what Apple terms Spatial Audio and it’s pretty good. You can switch between mixes on your iPhone and you’ll hear the differences, some a bit more surprising than others.

It’s kind of the Wild West out there at the moment in terms of how the DSPs work with it. Tidal has it. Amazon music has it. Spotify is yet to adopt it and a lot of people are watching to see how that goes but Apple certainly is doubling down on Atmos. Even that is a moving target because the way Apple Music sounds today is different to how it sounded a year ago. I guess they’re taking the feedback of listeners, engineers and trying to incorporate that into the codec. So it’s tricky. It really is tricky.

REGRETS?

AT: Now that Atmos is gaining a bit more momentum, are you happy you took the plunge and got involved?

TH: It was definitely worthwhile and I’m genuinely glad I did it. Any opportunity to upskill in audio is worthwhile. Even though it was a fairly big outlay, I knew it would be a missed opportunity not to do it, and it’s now paid for itself. Labels and managers don’t want to have to ask to get the stems and then send them to some other guy for the Atmos mix — that’s a really big thing right there. You’re always trying to find those one-percenters that make you stand out as somebody people want to go to. I’m always looking for that. This is the first time in a long, long time that there’s been a lot of investment by big companies into the audio engineering side of music, and because this format is scalable, it still has the momentum.

I know the Dolby folk really well. They were really helpful to me setting up my room. Ceri Thomas, who now works at Apple, is a great guy and it’s been really cool getting to know those people and hear how they think about the format. We’ll see where it goes.

I really don’t know what the longevity of it all is, but I think it’s very safe to say that some version of this is here to stay purely with all the VR gaming possibilities. It’s got to somehow stick around.

RESPONSES