Mix Masters: Björk Empowers Marta Salogni

Bjork Empowers Marta Salogni.

Artist: Björk

Album: Utopia

Despite progress made in combatting sexism, the numbers still don’t favour women in the music industry. An Instagram account called ‘Lineupswithoutmales’ appeared just prior to International Women’s Day and documented the imbalance by editing festival posters to leave only female-represented acts on the bill… some were left plain empty. DJ Mag’s 2017 readers’ poll collated a similar imbalance when its list of 100 most popular DJs featured exactly three female DJ acts. In recording studios, the ratio is similarly lopsided; female engineers, mixers and producers are estimated to fill only three percent of control room Herman Miller Aerons.

Other awards haven’t fared much better. The recent #metoo movement famously fell on deaf ears during the 2018 Grammy Awards ceremony, as the results simply confirmed the skewed reality. Only one female artist, Alessia Cara, won a major Grammy Award (for Best New Artist), while a meagre 17 awards (out of a total of 86) went to women or female-fronted bands.

This year’s British Music Producers Guild Awards had a different look. Five of its 16 MPG Awards went to women, including some of the most prestigious awards, like UK Producer of the Year, awarded to Australia’s own Catherine Marks (on the cover of Issue 94). In addition, Manon Grandjean received the Recording Engineer of the Year Award, and Marta Salogni the Breakthrough Engineer of the Year Award. The other two were non-studio Awards, for Jane Third (A&R) and Imogen Heap (Inspiration).

ALTERNATIVE POWER

More than 25 years ago, I wrote an article about the dearth of women engineers in London studios. One studio owner remarked, ‘The rock ’n’ roll industry is one of the most racist and sexist industries in the world.’ The 2018 MPG Awards may be a sign biases are improving in Britain; Salogni’s own meteoric rise to the top of the London studio game seems to indicate as much. Yet Salogni says it wasn’t all laid out smoothly before her. “I always have to exceed expectations in the beginning,” she said. “People go, ‘That’s strange, a woman in this job.’ It means I have to do my job better than anyone, to justify the fact I am still a rarity.

“Being a kind of exception is both a good and a bad feeling. Good because it feels empowering to be part of a ‘change’; I’m not only exercising a passion and a profession, but also providing an alternative to the status quo. Bad because it can feel isolating and uncertain, as I have very few role models to look up to. There are so few female engineers, mixers and producers in the industry that when I started my career there were moments I doubted my chances of succeeding. I speak to many young people now who are trying to understand how to make it in such an unpredictable industry. Lots of them, especially women, tell me that seeing someone like me successfully navigating this industry makes them feel more confident in themselves.”

GROUND MADE AT MPG

For Salogni, the MPG Award was the icing on the cake after a particularly exciting and successful 2017, in which she, amongst other things, mixed most of the latest album by one of her favourite artists, Björk. Salogni mixed eight out of the 14 tracks on Utopia, and mixed vocals for two others. With New York-based Egyptian mastering engineer Heba Kadry mixing the other six tracks, and Mandy Parnell mastering, Utopia’s final stages were entirely delivered by female hands. It befits the theme of female empowerment; one of several subjects Björk explores on Utopia.

Salogni wasn’t aware of Utopia’s subtext when she received a phone call from Björk in July 2017. “It was quite an incredible moment to suddenly have one of your favourite artists reach out to you,” she said. “Björk can get whoever she wants to mix her albums, and the fact she chose to work with so many women on her new album is quite powerful. It certainly also helps to defeat the preconception that mixing or mastering is a man’s job, and will hopefully inspire young women today. The initial request I received was to mix two tracks from Björk’s new album, to see whether my style would fit. I did those two mixes at my studio, and the feedback was really positive, so Björk asked me to mix more songs for her album.”

Salogni getting the call was a reflection of how far the Italian has come since moving to London in 2010, fresh out of secondary school. Salogni grew up in northern Italy, not far from Milan. As a teenager, she developed a keen interest in art in general, and music and sound engineering in particular: “I saw music and manipulating sound as similar to painting. It’s a form of fine art.”

Salogni also took an early interest in synthesisers, which she calls “democratic,” because “to play a guitar, for example, one is traditionally supposed to know how chords work, what the finger positions are, and so on. Synths instead can be explored without any musical training, and with only the desire to create something new. Synths are intuitive and creative, you can sculpt away to find sounds that are unique.”

WRENCHING ON TAPE MACHINES

After arriving in London, Salogni attended Alchemea Music Production College, which taught her the “rudiments of recording and Pro Tools,” and gave her experience on the college’s three consoles. Upon completing her course, Salogni got a job in the audio department of a movie post-production company, but realised she really wanted to work in recording studios and landed herself a job as assistant to producer Danton Supple. Initially working from Dean Street Studios (formerly owned by Tony Visconti), Supple and Salogni went on to work at Strongroom Studios in East London. It was here that Salogni met one of her main mentors, star mixer David Wrench. She became Wrench’s assistant, and today Salogni still works with Wrench as an engineer “if projects and schedules align, but I now mainly mix and produce my own projects.”

By the time Björk’s team contacted Salogni, the Italian had clocked up credits with Glass Animals, Goldfrapp, White Lies, and The XX. While popular acts, they all lean to a more experimental musical vision and sensibility. Salogni’s own taste skews to the psychedelic electronica of White Noise’s Electric Storm, and avant-garde album The Feedback by Il Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, which featured a young Ennio Morricone on trumpet.

Salogni’s experimental mindset is exhibited in the way she wrangles the two-track tape recorders lining her room at Mute Studios in West London. “I have a weird relationship with gear,” explained Salogni. “I always try to make it do stuff it’s not designed to. I want to be in partnership with machines, rather than stay within their limits. For this reason I am fascinated with tape recorders. They may seem dated to modern musicians and engineers, but when I first encountered one a few years ago, I thought, ‘wow, this is beautiful!’ Magnetic recording is a beautiful concept, and I do all sorts of things with these tape recorders, like use them as delay units, or to create polyrhythms, saturation, distortion, and feedback. Given that they were purely built to record, I think that’s pretty good! It’s why I have several of them: the Revox PR99 MK III, Akai 4000DS, Ferrograph 5A and a Davoli Echo Mixer. I’m completely in love with them!”

Salogni’s studio also contains quite a bit of analogue outboard and a collection of synths and drum machines that belongs to Mute owner Daniel Miller, including a MiniMoog, Polyvox, Roland TR303, Roland System 100, Sequential Circuits Pro One, System 100 and more. All the synths are hardwired into an an SSL Matrix desk, which is the heart of Salogni’s mixing setup, alongside a Pro Tools system, Dynaudio BM15 and Adam A7 monitors, and a Pure consumer radio.

STEM ORIGINS UNKNOWN

With just stems to work with, Salogni didn’t have much cause to inject her tape machines and synths into the mix. She simply dove right into the ’Tools session. “I started almost the moment I put down the phone,” she said. “They sent me the Pro Tools sessions for The Gate and Arisen My Senses. The session for The Gate contained only 13 stems, so there was a minimal amount of tracks. As my mix developed, I split the main vocal stem and the main processed stem to be able to treat them differently for different moments of the song. Some additional stems arrived from Björk, giving me a total of 16 stems to work with.

“Normally when I start mixing a track, I spend an hour colour coding and naming, then I order the tracks with the drums at the top, the vocals at the bottom and the instruments in the middle. Within that structure I also place the tracks in the order they appear in the timeline. You must have some kind of method! In this case it was not obvious how to order the tracks, because there was no traditional band structure to indicate what the instruments are and roughly what they have to sound like.

“You know what a kick drum has to sound like, but here there would just be percussive tracks with high end and low end. Also, normally I go through the tracks one by one and EQ things, but in this case all the elements are interconnected. I could not go in and EQ individual tracks, and expect it to sound better. Some of the stereo stems included a wide range of elements, and therefore frequencies, hence my use of multi-band compression. All elements on the stems are interconnected and need to be addressed as a whole entity, rather than individual parts. A big part of my process was working out what was in the stems, and how those things fit together musically; then, to find a way of organising my mix session and a way of mixing that worked.”

LOST IN THE ROUGH

The Gate eventually became the lead single of Utopia, something Salogni was not aware of while mixing. It’s a very spacious track, in free rhythm, with a backing of flutes and electronic sounds, a deep 808-like bass, some non-rhythmic percussion, and quite a number of backing vocals. Given Björk and her team, which includes co-beatmaker and co-producer Arca, had already managed to whittle down the mix to 16 heavily-treated stems, one wonders what they hoped Salogni would add. It was her question too, not made any easier by the lack of additional information or direction.

“I always start a mix from what I’m given because I assume that’s what the artist is comfortable with,” she explained. “The artist and producer will have been listening to the rough mix, and that’s what they’re keen on. My job is to translate that into something better. However, with these two songs they purposefully didn’t give me the reference mixes. I asked for them, and Björk said: ‘I want to see what you bring to this, completely from your own imagination.’ That was empowering and intimidating at the same time! I had no idea what their starting point was. Obviously I had to start from what was in the session, but they might already have created a killer mix, and I’d have absolutely no idea what that sounded like!”

Still, Salogni pressed on: “I was not going to add plug-ins to sonically transform the stems, because they already had such unique and definite sounds. Instead my main aims were to create clarity and let the dynamics flourish. In creating this track they had already thought a lot about the dynamics. I wanted to enhance them and make them much more extreme. I wanted to make the track euphoric in a way that really grabs attention, and have things jump out in the mix. There were only 16 tracks, but it still meant a lot of detailed volume automation that took a long time to do.

“Another aspect of the dynamics was to make things more spatial, width-wise. I am pretty bored with regular stereo. I like widening and making mixes as immersive and three-dimensional as they can be, while at the same time being respectful of the space that elements are meant to have. During subsequent mixes Björk gave me insights that allowed me to maintain the natural stereo image placements of the choir and flutes, in accordance with their positioning in the church or hall where they were recorded. However, for the first two tracks I mixed in London I had no idea and had to go with my instincts. I think that’s also why I was given stems, so I had no option but to preserve the panning!

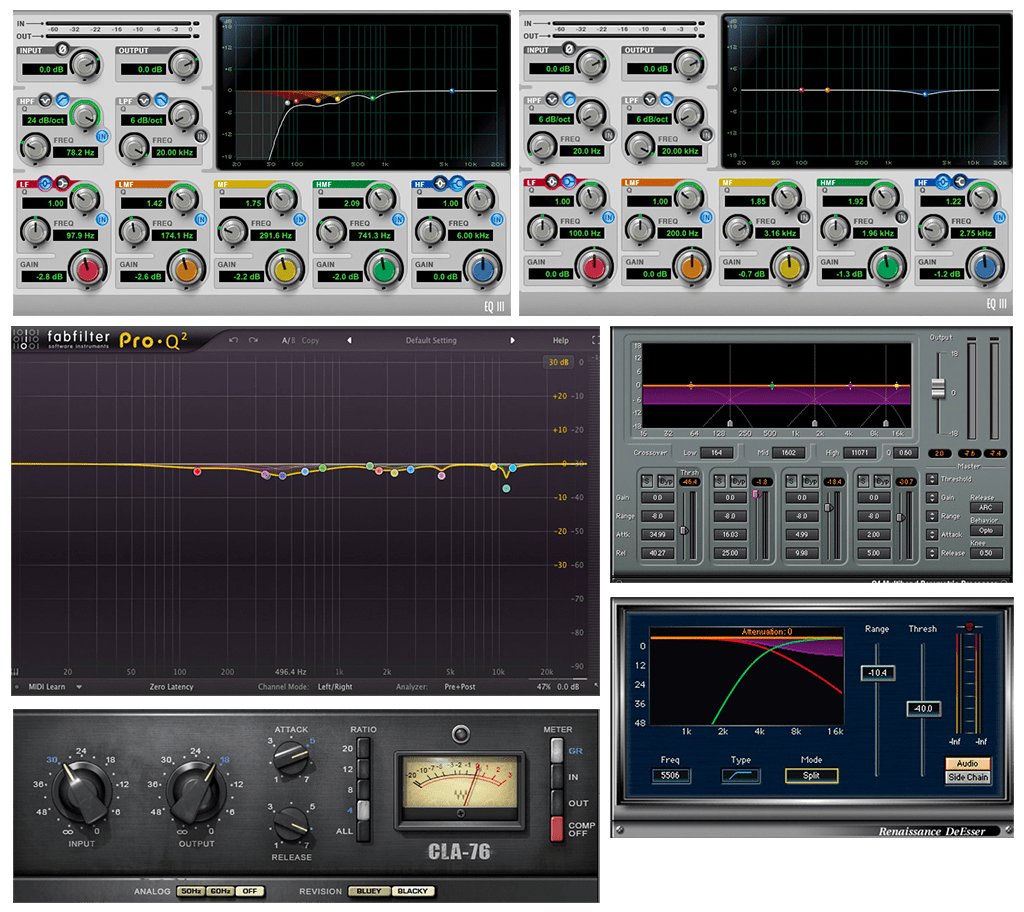

“With regards to clarity, I always do a lot of subtractive EQ, applying it immediately after I have organised the session. Unnecessary low frequencies take a lot more space and can create a lot of mud. I use two EQs for this — the Avid EQ3 7-band and the FabFilter Pro-Q2, because they are the most neutral-sounding. If there’s still a frequency that annoys me, I’ll use another Q2 to sweep the frequency range and take it down. I then bypass the plug-ins to see if I’ve made an improvement. In general I am not a fan of 200Hz, 400Hz, and 600Hz, basically all the harmonics of 200Hz. I also don’t like 3kHz and 6kHz. The beauty of creating space by taking out frequencies is that you then have space to boost one thing. In general I like to use several different EQs in series. It’s a matter of mixing up different colours.”

MIXING IN BJÖRK’S BACKYARD

Salogni stressed that her overall aim when mixing The Gate was “to polish what they had done, to give it justice, to keep some elements on top of others, and also make sure everything felt like it belonged in the same world. The vocals had to be intelligible, but also not overpower the instrumentation. The low end was really important, and I wanted to give that as much impact as possible, while ensuring the high end was not piercing.”

Salogni was clearly successful, because “after I sent my two mixes to Iceland, the feedback was really positive, and the changes I was asked to do were minimal. That felt amazing, to have been able to interpret Björk’s vision. When Björk then asked me to mix more tracks, she said, ‘should I come to London, or would you like to come here to mix?’ There was a time constraint in that she could be in London for less time than I could be in Iceland, so I suggested I head over. There’s also an obvious connection between her music and the Icelandic landscape and culture, plus she could stay close to her family.”

Björk and Salogni worked on the mixes for Utopia in Reykjavík in a new studio complex that belongs to engineer and trombone player Bergur Þórisson. “We were set to go to a studio that was fully equipped and sound insulated, but it wasn’t available, so Bergur offered his studio. The room wasn’t finished yet, and not sound insulated, which meant it was quite hard to work in because I’m used to super-dead spaces without leakage. It was challenging, but I actually loved it, because it really pushed me to my limits. Björk and I really wanted to make sure the songs would sound good on any system in any room, so I asked for as many speakers as I could. We listened to Auratone 5Cs, Adam A7s, and Amphion Two18s with an Amphion BaseOne25 subwoofer. We also listened in Bjork’s car, on her Genelecs at her house, and on Beyerdynamics DT770 headphones.”

Salogni mixed another six tracks while she was in Reykjavík, plus vocal mixed two more. Overall, her mix approach for the tracks was similar to that of The Gate, but sitting in the same room with Björk during this process proved a big help. “She would give me a lot of background information about the recordings and song concepts, which was very important to me. She was really good at communicating what she wanted, often combining words, gestures and images. If something still wasn’t clear to me, she would just show me in Pro Tools what she had in mind. She’s really good at Pro Tools, and that was also very helpful.

“While I was in Reykjavík I did further tweaks to The Gate and Arisen My Senses, and another thing that made a difference was getting to see the video for The Gate. That changed my perspective. It helped me not only understand the feeling she’d explained to me, but it also clicked visually. I went in and did some more automation inspired by the video. For example, the moment the low frequency sound comes in, she makes a movement with her hands and I wanted to replicate that in the mix. I wanted that moment to be as impactful as possible, and had the trim automation up by 4dB or more. I love music videos that have a strong connection with the music. Working in post-production, whenever the visual cues and music cues matched, it created another level, a fourth dimension.”

RESPONSES