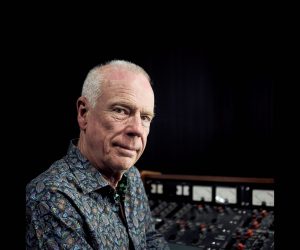

Mitchell Froom

Mitchell Froom has been on the vanguard of innovation in his many years as a record producer. Mark O’Connor discovers how to maintain a fresh perspective.

In a music industry where ‘bling’ has come to mean more than ‘sing’ and anyone who can manipulate a spacebar calls themselves a producer, Mitchell Froom’s career has been characterised by the very thing that an increasingly fashion-driven industry recoils from: idiosyncracy, a distinctive identity, and the ability to amplify the eccentricities of the artist he is producing. His productions are built to last… at least beyond the next fashion glitch.

Froom’s talents as a producer have attracted some of pop music’s most enduring and distinguished names – Elvis Costello, Paul McCartney, Randy Newman, Sheryl Crow, Suzanne Vega, Los Lobos, Bonnie Raitt, Ron Sexsmith, Richard Thompson, and of course Crowded House, whose self-titled debut album (at the time only his second production effort) launched the careers of both artist and producer – marking the beginning of an ongoing creative relationship which extended through the band’s second and third albums to the present day. Finn brothers Neil and Tim have jointly and severally enlisted his talents on solo albums and recently reunited with him as producer for their Everyone Is Here album.

Froom’s career is notable for many such ‘repeat engagements’. “That’s the goal,” Froom observed in our recent phone conversation. “The best case scenario for me is to work with an artist on several albums where we try to develop something and then take it further, and then further still.”

However, as Froom himself observes the business of making music has changed.

“It was far easier to do that when I started. If people worked well together on an album, getting those same people together again a second time ’round was positively encouraged. These days the business tends to discourage it – unless it was massively successful. If I had produced the first Crowded House record now there’d be a high likelihood that they would say, ‘Well that’s great, now if we get this guy [for the next one] then we’ll really sell a lot of records’. If I hadn’t worked on the first Crowded House record but was contacted to do the second, I’d be looking over my shoulder and worrying, ‘Is this as good as what the first guy did?’, whereas if you’ve done the first one then you know how that went and now you can take it further.”

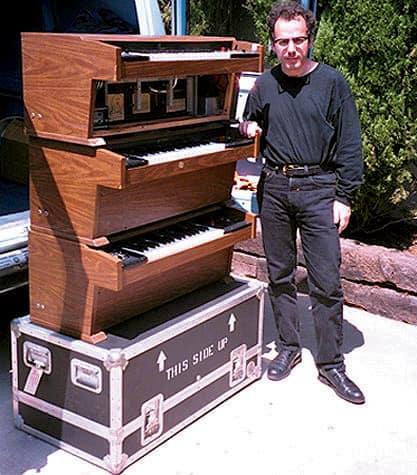

Froom wasn’t looking over his shoulder during the recording of his latest production success, the self-titled debut album for Canadian artist Daniel Powter (more on that project later), which has quickly become a worldwide hit. I spoke with him recently by phone from Los Angeles to discuss the making of this and other albums, and about what it is that distinguishes his work. I suggest a certain ‘organic’ quality to his records which perhaps derives in part from the prevalence of authentic ‘real’ instruments played by musicians – Wurlitzers, piano, chamberlin and organ (never so devastatingly employed as in the case of Froom’s own Hammond solo on Crowded House’s Don’t Dream It’s Over, that one performance perhaps single handedly responsible for a subsequent resurgence of that instrument in pop music) instead of synthesizers; real drummers as opposed to drum machines.

“I will say that I’m attracted to music that has feeling, and if that leads me in a direction that may be defined as ‘organic’ – that is, people playing music somehow – then that’s fine with me.”

My main aim now is to push forward whatever the artist’s eccentricities may be – their singing, whatever musical originality they have – so that it’s front and centre

TCHAD BLAKE – FROOM MATES

The other defining aspect of Mitchell Froom’s production is reliance on long-term collaborations. And one of the great studio tag-teams of recent times has been fruitful and long-standing partnership with engineer Tchad Blake – a relationship that began with the first Crowded House record.

MF: Tchad was assistant to an engineer we had to fire because Neil [Finn] hated the guy – he was a real pain in the ass. So I just turned to Tchad and said, “Will you just take over until we mix”. He was already a good engineer and I was looking to find someone I liked and could trust with the sound, so I figured ‘We’re both starting off, let’s start together and see how far we can take it’.

‘Far’ indeed. Froom and Blake have since made some of the most innovative pop music of our time. Along the way they developed an idiosyncratic sound that owed more to distortion than to reverb. Their recordings were increasingly characterised by the quirky sonic manipulation of instruments and sometimes entire rhythm tracks, often radically altering their character while still maintaining their essential authenticity and organic nature.

MF: There was a real breakthrough moment for Tchad and I while we were working on a Los Lobos record called Kiko (1992). We’d just gotten this pedal called a Sansamp, which was designed really for guitars. David Hildago of Los Lobos brought in this four-track demo of a song he’d done, and in it there was a lot of really distorted percussion that sounded beautiful. The recording sounded like an old record – it had all this atmosphere to it. The band had also recorded another version of it that was really clean. As I remember it, Tchad had the pedal so we tried putting all the percussion through it to see what it would sound like, and for me, at that moment it was like the sea parted or something. The percussion rhythm section suddenly sounded like some Cuban recording from the forties. And when it was mixed in with these beautifully recorded acoustic guitars, everything had its own range and its own space and the recording was twice as atmospheric. As soon as that happened we just went crazy and just tried it on everything! It was a watershed moment and the beginning – as far as I remember – of our experiments with things like that. It wasn’t scientific, it was always something very simple and usually in the spirit of goofing around.

It got to the point where I became very interested in arrangement and if something sounded boring we’d say, ‘Well what if we get rid of the snare drum and put this instrument up and run it through that effect and see what that sounds like’. We were just trying to please ourselves and have fun. We were working on the idea that recording should be a time to explore, where you try to get something that sounds good to you at the time and that’s all that we ever did.

MO’C: With Tchad now based in the UK, do you think you’ll hook up again?

MF: I miss working with him and he misses working with me. But over the past two years I’ve found a new guy, David Boucher, who I’m really excited about working with, and some of the stuff we’re doing is really great. It feels new to me again so I’m happy about that. And Tchad’s off doing his own thing too, so… if a situation arose, that would be great, but it doesn’t seem likely in today’s climate with its financial constraints. I doubt if people are gonna come to us and ask us to make some weird-ass record (laughs)… it’s just not gonna happen.

I’m less and less interested in working like that now anyway. There was a period of time in some of my work with Tchad where people started to say, ‘your production sound is so powerful, that sometimes it overpowers the artist’. Nowadays I’m interested in being much more transparent and just seeing how powerful I can make the recordings, with no ‘stamp’. My main aim now is to push forward whatever the artist’s eccentricities may be – their singing, whatever musical originality they have – so that it’s front and centre. It’s always been the basic concept, but now I think I’ve gotten a bit better at it.

Tchad had the SansAmp pedal so we tried putting all the percussion through it to see what it would sound like … at that moment it was like the sea parted or something

DANIEL POWTER

MO’C: Can you tell us a little about the recording of the Daniel Powter album and how you came to take on that project?

MF: Usually with an artist I’ll listen to what they’re doing – usually some kind of demo – and if I have ideas that the artist likes then that opens the door to possibly working together. I keep it at the basic level, and because everyone is so paranoid nowadays, I’ll just suggest that we start working on something and see how it goes. I’m most interested in keeping it about the music, so there are no ego problems or anything of that nature getting in the way of it. If there are things getting in the way then I’m usually not interested in pursuing it.

Daniel’s was a more unusual scenario. He had recordings he’d been doing for a number of years with his partner Jeff Dawson, and suddenly they became the subject of this huge bidding war. Then once the record deal was signed there was all this pressure on them. Initially the label was pretty hesitant about me working on it – I suspect they didn’t think they were my musical ‘bag’. So I said, ‘Why don’t we just work for a couple of weeks and see how it goes, and if the label aren’t happy and if you’re not happy, we’ll just stop’. So we worked for a few weeks and then the ‘label guy’ came down – ironically it was Tom Whalley who signed Crowded House – and he heard what we were doing and said ‘fine’. So we just kept going.

But the task of opening up and improving upon the original tracking was a very difficult one. A lot of it had problems, but I knew that it would be a loser’s game to try to re-record everything. For the first couple of days I just sifted through stuff going, “What is this? Who decided to do that and why?”. So we tried to figure out techniques to improve the sound of things and then identify where the problems were. David Boucher [Mitchell’s engineer] and I just made the sound more full-frequency, and injected a little more rhythm into the music – a lot of it was piano, pads and different rhythms so we tried to make it a bit funkier. But ironically, the whole process took longer than it normally takes me to do a record from scratch, but it was important to do it that way because it wouldn’t have been right for him to start over.

MO’C: Is that the norm for you? I imagine that you would more often be in a situation where you could work things up from scratch.

MF: Yes that’s true, although there have been a number of records in my career where I’ve done that – the second Sheryl Crow record, the most recent Finn Brothers record, and even to some degree Crowded House’s Woodface where I started the record, then Neil and Tim did a bunch of things on their own and I came back in at the end to try to make it all work together. I think in the future it may become quite commonplace. The only thing that I don’t like about this approach is that you don’t get the chance to really conceptualise the way you think an artist should go because some of that is already being defined for you.

MO’C: I recall an interview with Randy Newman after you’d produced his Bad Love album where he observed that you work very quickly, certainly faster than he was used to.

MF: Yes I do, I work very quickly. Everybody has their own way of working, but if I was to describe the way I work, I would say that relative to other people I work incredibly short hours and then I spend all night thinking about it. Then I come in the next day with good ideas. I get really confused if I’m working very long hours in the studio. I don’t think it’s possible to hear the same song for more than seven or eight hours and have any kind of idea how to solve the problems that are presented to you. That’s just me. I think some people are probably successful at it but if there’s a problem I’ll just say, ‘Ok, we’ll come in tomorrow’, and then I’ll think about it all night and in the morning I’ll usually have a much more insight into how to solve that problem – rather than chasing my tail in the studio.

MO’C: You mentioned earlier working up the rhythmic aspect of the Daniel Powter album, which prompts me to observe that a lot of the records you’ve produced have been characterised by a strong rhythmic component.

MF: I just love great drummers. It’s always been one of the main things that I’ve been interested in – the way a song feels. Even now I’ll look back at some things and think, “Well, the drums were really well played but they could have been tuned in a way that would have been better for this music”. My favourite music has always been music that operates on a number of levels, where people can just get the visceral feeling of what comprises a great groove – that’s beautiful – and then the musicality of it. Then there’s the lyrics and the way they sing. And when all those things work together it’s tremendous! Even when it’s electronic, there’s a way of doing it such that it has a real feeling to it.

FROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT?

Froom was recently approached for a retrospective on Richard Thompson for whom he had produced five albums from the late ’80s through to the ’90s. It afforded him an opportunity to reflect on how he had perhaps evolved, and to what degree his work has withstood the test of time.

MF: The ’80s were a pretty cheesey time in music, a time of really ugly digital reverbs and people used them to a large degree. I was very happy to try to leave that behind because I couldn’t hear the instruments very well with all that.

So mostly what I heard was things I would do differently. But in retrospect I think maybe I was a bit too hard on things I’ve done. I’ve come to realise that producing records is all about popular recording. There were certain musical gestures and things that people did in the ’80s that were just what was happening and exciting and new at the time. That’s what people did. Later I can hear it and go ‘wow, that’s just off’ or ‘what was I thinking?!’, but at the time I didn’t feel that and neither did the artist and neither did anybody else in the room. Certain records seem to last better over time than others, and at the point where everyone’s very pleased with it and you’ve worked hard on it, you just have to let it go. And later you need to judge it with a softer critical eye perhaps…

The fact is, albums are designed to be of their time. Everyone hopes that their records are going to endure like Beatles records but it doesn’t always work out that way.

RESPONSES