U2 Live

World tours and rock ‘n’ roll juggernauts don’t come any bigger than U2’s Vertigo tour. Nor do the profiles of its four main protagonists. Managing the audio on a tour of this magnitude takes experience, expertise and a lot of composure. Enter two of the world’s best: Joe O’Herlihy and Dave Skaff. AT caught up with them both on the Melbourne leg of the tour to find out how anyone steers such a beast around the world without incident.

U2’s Vertigo tour is a total juggernaut. It’s been underway, off and on, for over two years, filling stadiums around the world. I had the pleasure of eating my way through a variety of dead farm animals with U2’s monitor engineer, Dave Skaff, at a Richmond steakhouse just prior to the Melbourne dates. Dave’s been with the band since 1985… and the tales he could tell. They were ‘off the record’ stories, of course, but mostly the gist of what he had to say was: yes, U2 are a bunch of regular, easy to get along with, guys, but you can be only so ‘regular’ when you’re part of an enormous machine that is a U2 tour, and you can be only so regular when there’s so many extraordinary demands on your time. To give you an inkling, it’s the type of machine that not only has a duplicate PA in Auckland waiting for the New Zealand leg of the tour, but also has yet another duplicate PA cooling its heels in Japan for when the machine turns like an aircraft carrier towards the far east. And the front of house PA alone consists of nearly 160 Clair S4s. It’s all just mind boggling.

And just by way of another indication of the size and complexity of the machine, on the day of the first show at Docklands Stadium (I won’t call it the Telstra Dome, because next year it’ll probably be the Dodo Dome or the Supercheap Superdome) no one was expecting a soundcheck. Or at least they weren’t until 4:30am, when a ‘day sheet’ was slipped under everyone’s door with news to the contrary. Even the tour’s audio director Joe O’Herlihy, who’s been mixing U2’s front of house sound for 28 years, didn’t know about it, and had to wait for the nod like everyone else. It’s not because Joe doesn’t have an opinion about whether to soundcheck or not, but who knows… Bono might have a date with Kofi Annan, or Nelson Mandela, or, erm… Peter Costello. The variables are enormous, and regardless of whom you are or how big a cog you are in the U2 machine, you’re still just along for the ride.

VERTIGO – NEW HEIGHTS

Joe O’Herlihy is concert-touring royalty. He’s more than a bit Irish and his career kicked off with a couple of world tours with Rory Gallagher in the early ’70s. He then met a band of four young blokes called U2 in 1978 and he’s been their audio lynchpin ever since, circling the globe more times than Skylab.

In really broad terms, the Vertigo tour is significant – on a technical level – for two reasons: it’s U2’s first tour with digital consoles, and also because it’s probably the only large-scale stadium tour that doesn’t use line array. As I mentioned, there’s more than a touch of blarney about Joe, and no sooner had we shaken hands he, unprompted, was telling me the whole story behind the move to digital.

JO’H: Back in July/August of 2004, when preparations for this tour started, we decided to move to digital. At that point the D5 was about the only console that had been bounced around in trucks and had done its thing. It’s a very good console and it made the transition from analogue quite easy – you can step up to it and get to grips with it very quickly.

CH: Was the change to digital a real life-changer?

JO’H: Undeniably, it gives you access to an incredibly good starting point for each song. I know all the other consoles are only a push of a button away from exactly the same thing, but when you make that initial transition from analogue to digital, all the things we used to dream about in the ’70s and ’80s are now possible. Take, for example, the Zoo TV tour back in the early ’90s… we had four guys mixing that, banging on all the bells and whistles we needed after the Achtung Baby album came out. We were one of the first to be using Midas XL4s for that tour and fader automation was only just happening. But now snapshot automation has changed everything. I’ve got 90-odd songs programmed into the D5; I can call any of those up immediately and have a solid basis to start mixing. And U2 is notorious for its spontaneity. Bono will turn around to The Edge and say ‘I Will Follow’, and it doesn’t matter where he is in the set list, that’s what they’ll play next. And in a split second I can call that song’s snapshot and start mixing. Some people might accuse digital of making things more programmed and predictable but personally I think digital technology assists with that spontaneity, it doesn’t hinder it.

CH: U2 embodies ‘stadium rock’, but stadiums aren’t built for hi-fi audio reproduction. How much time do you spend fighting the acoustics of these places?

JO’H: A stadium will kill you if you fight it. You need to find the building’s niche where the system will sit coherently with substantial intelligibility. That may not be the loudest possible mix that you would want but at the same time you have to trade away some blood, guts and thunder for intelligibility, quality of audio and sonic value. Making that judgement is down to years and years of experience, and makes coming into a new [for U2] venue like this, not so scary – I feel good about the show here tonight.

CH: In the end you don’t want to lose that sense of danger that differentiates an enormous show from a club gig do you?

JO’H: If you went into a stadium where you could set up and then just walk away from the console and have a cup of tea… well, there’d be no need for people like myself, and my systems engineer, Joe Ravitch. We take pride in getting the best out of challenging acoustic environments. And if there wasn’t an edge or a fear factor about it, you wouldn’t get that adrenalin push when you’re making something like this work.

CH: Increasingly, people go to concerts expecting a ‘produced’ CD sound. Is that something U2 continues to resist?

JO’H: These days you can produce a pristine CD sound, but for U2 it’s never been about that. It’s about the adrenalin that’s associated with the performance – it’s edgy and there’s a fear factor there. There’s a dynamic there that you will only get with a live performance.

CH: Current line array rigs have been at the forefront of providing CD sound. Many will be surprised to see you using old-school Clair S4s here.

JO’H: Yes, people will say that’s old technology. But it’s all about going into the character of the stadium… it’s all about moving air… it’s about having all that extra wood and cardboard hanging in the air. The band produces a sound on stage and they have an expectation of how that sound translates to people in the audience, and when it comes to stadium shows the S4 allows me to replicate what comes off stage in the way the band perceives it. It’s rock ’n’ roll, and that’s what you see there [pointing at two acres of S4] – rock ’n’ roll!

Having chased him around the major scaffolding structures of the world from stage to stage and festival to festival over the last 28 years, I can tell you quite categorically that [Bono’s] good at delivering.

ANATOMY OF A MIX

CH: Can you run us through some inputs Joe?

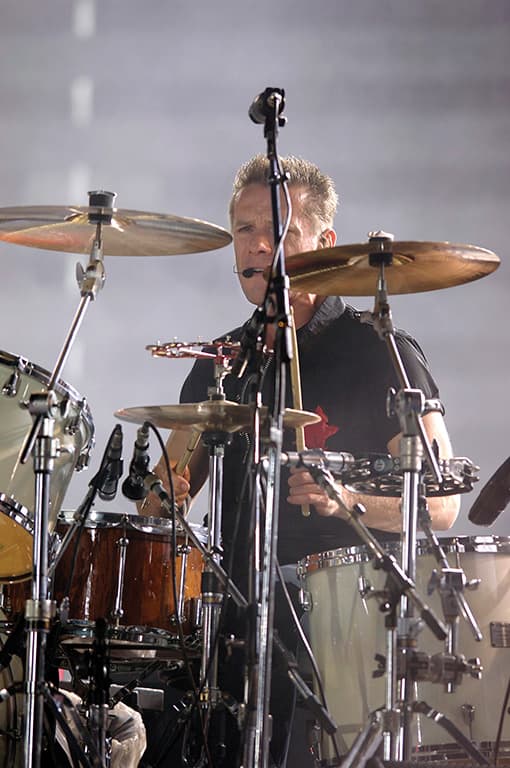

JO’H: Larry has 20-odd channels for his drums [see the drum caption for details on the drum mics], while Adam’s sound is comprised of a DI, a bass mic sound, a bass effects sound, and a Bass POD sound. The blend of all those gives you the body of the bass sound, which I combine with the drums – Larry and Adam are the foundation upon which I build the mix. The layering and colouring that happens after that will depend on The Edge’s domain, his guitars and the keyboard parts that he’s arranged. The Edge’s guitar world comprises eight different guitar amps. We’ve got two Vox AC30s on stage and another one under the stage miked up in a box. Then there are four vintage Fender amps on stage along with a fifth in a box. At any one time the guitar sound might be comprised of a signal routed through any combination of those amps. The Edge will structure it himself on stage, routing his guitar through, say, Vox 1, Fender 2, Vox 2 then the Fender in a box. Or it could be Fender 1, 2, then 3… the elements change from sound to sound. For example, he might have a solid, grungy, crunchy guitar sound coming out of the Vox, which might be followed by a trailing echo coming out of a Fender. I’ll get that combination with those individual amp sounds coming up their own channels on the desk, where I’ll need to make decisions on the exact blend that will suit the space. What might be right for one particular place might be really shrill and abrasive in another, so I’ll make adjustments accordingly. So apart from The Edge’s VCA I’ll be looking at a group of faders right next to the VCA section, constantly checking on guitar levels, seeing that I’m getting a full-value signal.

CH: Last, but not least, there’s Bono’s vocal.

JO’H: That’s right, there’s Bono’s vocal on top of all that and his effects – reverb, slap echo, multiple repeats. And backing vocals – The Edge does a substantial amount of that. We’ve got three Bono vocal channels, so if Bono drops a mic he’s immediately got another. We use Shure wireless with a Beta 58 headstock.

CH: And no problems getting a decent level out of Bono, I’d imagine. He’s got a classic stadium rock voice.

JO’H: There’s real power and energy in his voice and his mic technique is magnificent. He’s learnt from a very early age that you’ve got to put in the effort. Having chased him around the major scaffolding structures of the world from stage to stage and festival to festival over the last 28 years, I can tell you quite categorically that he’s good at delivering.

MONITORS – DEEP UNDERCOVER

Dave Skaff’s shtick is that he’s been working with U2 for over 20 years and he’s not once seen or heard the show. It’s not entirely true: he worked front of house for one of the tours, but it’s a nice line to confound people who don’t understand what a monitor engineer does and where he does it. The Vertigo monitoring position is particularly tucked away. If, like me, you’re over six foot, then life would be painful – I found myself ducking and concussing myself much of the time. There’s no direct line-of-sight link with the stage, it’s all via a closed circuit TV.

Shoe-horned into the space are Dave’s two Digidesign Venue consoles (one’s a backup and mostly used to track live recordings they’ve been doing to ProTools), while two deputies monitor mix for Bono and The Edge (Robbie Adams and Niall Slevin respectively, on a Digico D5 each). Yes, that’s right, a total of three monitor engineers. As Dave says, “they’ve earned it”. And – I suppose it should come as no surprise these days – there’s not a single outboard graphic EQ to be seen. There are a few racks of ‘special sauce’ mic pre’s, but Dave does not use a single graphic, that’s all done within Venue via an EQ plug-in from Serato.

CH: Dave, you’ve been mixing monitors for U2 for a long, long time. Your job must have changed beyond all recognition since the late ’80s, what with the introduction of in-ear monitors and now digital consoles.

DS: Sure. I remember that at one point we had 75 boxes on stage – we carted an entire truck full of monitors… it was over the top. Now the focus is more on control and precision mixing, and less about speakers filling the stage.

CH: So, back ‘in the days’, mixing monitors for a big stage was bit of a knack or an art, rather than a precise science of balance engineering?

DS: In the old days you did stage sound. The most successful guys were the best at creating an environment that was conducive to good performances – where musicians could not only hear themselves but feel inspired. For example, we used to have a giant side-fill of low-end for Adam, while on The Edge’s side there was nowhere near that. Then the drum kit had a lot of support behind it, which led out to a big field to the centre of the stage for Bono. So there was loads of guitar coming out one side, loads of bass on the other and we created these pockets of sound – if you wanted to hear a different blend then you walked over to where you would get it.

CH: And now with in-ear monitoring I guess it’s about creating individual environments within each head.

DS: Right. And each of the guys is so different in the way they hear things. The main difference between mixes is obvious: ‘I want me louder than everybody else’ – but after that it gets into individual preferences. For example, Bono likes to have his effects quite prominent. The Edge is minutely concerned with the balance of things – all of his guitar amps, and the keyboard parts need to be perfectly balanced in his ears. Adam likes a very workmanlike mix, with no reverb, just really fat, and quite mono. Which is very different to Larry’s mix, which is this huge image of his drums from the overheads and really nice fat reverbs on the snare and vocals – it’s a hi-fi band mix, only with the drums up.

CH: Do you spend most of the time with your in-ear moulds in then?

DS: The whole show. I have a belt that has a couple of different beltpacks. I take one beltpack from each guy’s mix and I also take a console cue in from a hard wire. I have a little belt switcher. So during the show I have one hand over here mixing on VCAs and the other switching things on the belt.

CH: Anything in the way of conventional monitoring?

DS: Some wedges and some side-fill, all for low-end support really. And because a sub by itself sounds a bit odd we put a full-range box on top and wind up the amp a little just so you can hear it and tell there’s something in the sub. If the full-range boxes were doing anything more than ticking over you’d be making life difficult for yourself. One of the enemies of ‘ears’ is high frequency sound – midrange and above. The friend of in-ears is low-end, which supports what’s going on. I’m not trying to swamp the stage with low energy; it’s more about providing localised low-end fields – pockets of energy for guys to play where they feel comfortable.

CH: Mixing monitors on this sort of scale always strikes me as being about getting lots of ‘one percenters’ just right – a dB here, a dB there… Are you always keeping an eye out for something that can give you an advantage?

DS: You’re always trying to dig around for that extra thing. And now the thought of plug-ins in a live environment… it’s like a Christmas toy box… What’s new? What’s out? What’s on offer? The creative aspect of what you can do now is just amazing.

CH: Which leads us to your use of the Venue console. You were a very early adopter of Venue – before it had any real time to prove its roadworthiness… you must have had colleagues shaking their heads thinking, ‘I hope you know what you’re doing Dave’?

DS: There’s a long story that goes with the switch to Venue… but the short version is that the ATI Paragon I was using was having problems – I was blowing up power supplies. I was aware of the Venue and was attracted by what it could do. Anyway, there came a point when the Paragon blew up one too many times, and I said to production that it was time to make a change. I told them what I wanted and the reasons why. Production pointed out, and rightly so, that Venue hadn’t been out long enough – it’d been out maybe four or five months at that point. I stood my ground and told them I wouldn’t be asking if I didn’t think it was the right thing to do. I’m sure they walked away thinking – well, it’s his neck and he can have all the rope he needs! The band, on the other hand, were like: “this is what we pay you to do… it’s your call. We don’t care if it’s a cardboard box, if it makes us sound good then that’s what we want you to use.”

CH: And how did it go in the early days? Did you A/B it with a cardboard box?!

DS: Right! It was a tough first couple of days, ‘cause we didn’t have rehearsals. But by the time we hit the fifth show at Madison Square Garden… I got the call from the dressing room telling me how great it sounded. Then it was like [big exhale]… and it kept getting better and better.

the thought of plug-ins in a live environment… it’s like a Christmas toy box… What’s new? What’s out? What’s on offer? The creative aspect of what you can do now is just amazing

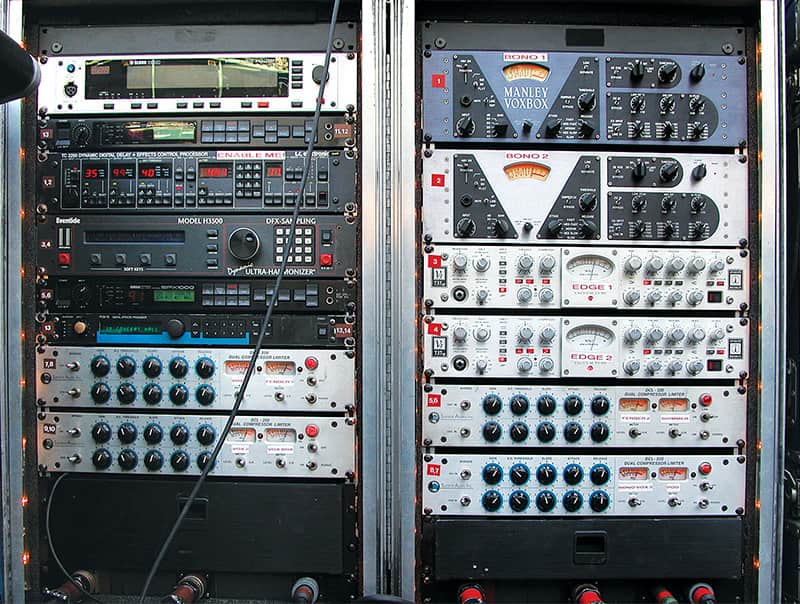

JOE O’HERLIHY’S FOH OUTBOARD GEAR

CH: Talk about a baptism of fire! Any readers reticent to make the change to digital should probably thank their lucky stars they don’t have the world’s biggest band listening to their every move. Any tips on keeping your sanity during a switch like that?

DS: I do actually. I’ve given it some thought and formulated a bunch of ‘rules’ that I’d refer back to if things weren’t going my way.

- Familiarise yourself with the console, because it’s not laid out like anything you’ve ever worked on. Plus, you can lay things out differently, so you really have to think about how you’ve got things arranged.

- Make sure you’re changing the thing that you think you’re changing. For example, make sure you’re on the right fader bank… Bear in mind, these are all things that I’ve been busted on… I’m speaking from experience!

- If you’ve never used snapshot automation before, then don’t use it when you’re getting started – if you’re not used to it, you don’t need it straight away, so don’t try. Instead, work through your show. Find out what it is that you really need to do. If those eight or 10 keyboard channels are going to bust you every time, then slowly think about how you’re going to use snapshot automation to make life easier – but don’t rush it. And finally…

- The console will do whatever you tell it to… or not. If you don’t tell it to do something, then it probably hasn’t done it. So while you’re standing there screaming, ‘why hasn’t it…?!’, the next thought has got to be, ‘did I tell it to do what I thought I told it to do?’.

As simple as they are, those rules have been a big help to me. If things weren’t going to plan then I’d mentally refer back to them.

CH: And now? You’re obviously happy with the way things have gone with the console?

DS: What I’m most impressed with, which was impossible to fully realise at the beginning, was how good it sounds. The depth of the mix that you get with it is amazing. You can run more and more into the mix and the imaging doesn’t get squashed – separation is still there, the range of tones is still there… And you’re hitting the console hard. So that’s the interesting thing to me, the depth of the mix. It’s a real musical mixer’s console. The analogy I use is, if you’re a professional guitarist you’ve probably played lots of great guitars, but one day you might find one that has that certain something that allows you to do what you couldn’t do previously. That’s how I’m feeling about this console.

Editor’s note: Subsequent to the scheduled end of the tour Dave Skaff took on a paid consultancy position at Digidesign.

RESPONSES