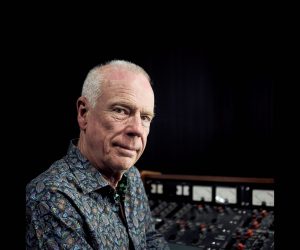

Lifetime Achievement Award: David Nicholas

From his first engineering credit on INXS’ Shabooh Shoobah to commissioning the first SSL knob that ‘goes to 11’, and co-producing Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart and Sting all at the same time, David Nicholas has been on one hell of a ride. To celebrate 2015 ARIA week, AudioTechnology and Studios 301 gave him the inaugural Producer’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

Photos: Wendy McDougall

Overnight, David Nicholas went from being a musician on the dole to owing a quarter of a million dollars. It was the ’80s, the only time in musical history when even a broke guitarist from Surry Hills with a bad case of GAS* could convince someone that investing in a studio was a good idea. “There was a lot of venture capital going around in the early ’80s,” remembered David. “I learnt that getting $250,000 from somebody was no different from getting $2000, you’ve just gotta be talking to the right guy.” Luckily Andrew Scott, David’s business partner, had a father who was the financial controller for Yates Seeds.

He guaranteed the loan that, at the time, was enough money to pick up a handful of Sydney properties. With it, David and Andrew bought the first SSL console shipped to Australia — an SSL 4000 series — and set it up at their newly minted Rhinoceros studio in Sydney. Neither of them had any idea it was the start of something big in Aussie music.

RHINOCEROS REBUILT

Up to that point David, like most sound engineers, had been a reasonably successful musician. He’d been touring the support circuit with his band, Limousine. They’d drive the M1 down the coast from Queensland to Port Pirie, occasionally stop to unload the truck, set up the PA, make some mischief and leave before anybody noticed. On the way home, they’d head back inland to places like Albury, Dubbo and Orange. Some of David’s more memorable moments included kicking off shows for Cold Chisel on their Set Fire to the Town tour and supporting Midnight Oil at the Royal Antler.

Back in Surry Hills, Limousine’s lighting guy owned a rehearsal studio called Rhinoceros that doubled as their home base and demo studio. But changes to Ordinance 70 meant all those tinder-lined wooden buildings had to get up to code by installing fire extinguishers and sprinklers. One day a contractor walked in and drilled two-inch holes through all the walls. It was a total disaster for acoustic isolation; he may as well have gutted the place. Which, the more they thought about it, sounded like a great idea! Shortly after, they invited all their mates to a ‘trash the studio’ party, turned the whole thing into matchwood and left.

With no place to go, a group of them decided to build another studio called Rhinoceros in a building on the corner of Goulburn and Riley Street, directly across from the looming Surry Hills Police Station. “Once, when we were doing INXS’ X album, there was a knock on the door at two in the morning,” remembered David. “I went downstairs to open the door and there was a guy dressed in full SWAT gear with a gun, balaclava, the whole lot. I just shut the door and ran upstairs. It turned out to be Mark Pope’s brother. He was a tactical response policeman and was coming for an interview with Hutch about doing security for their next tour! They thought it would be a really funny joke.”

With barely a pamphlet’s worth of knowledge about studio design between them, the rag tag collective lucked out when acoustician Richard Priddle agreed to help point them in the right direction. His lasting contribution was to instil in them the notion that good design is more important than exotic materials. They read magazines about studio design, aped the live room from The Town House studio in London and, having never got along with claustrophobic Westlake designs, decided to build the first Live End/Dead End control room in the country. “We were reading an article about the Tubular Bells guy who’d built the first Live End/Dead End room in England,” said David. “It made perfect sense to us because the only other studio I’d been into was Paradise, which had the Westlake design. That tiny, cramped space with rocks everywhere just didn’t sit well with me at all.”

For a year, the group of musicians lived onsite, slowly massaging the building into a studio. David even put his electrician’s apprenticeship to work wiring the whole place up: “The only things we didn’t do were lay the carpet and put the glass in.”

Because they were living in the studio while working on it, any jutting out corners were sawn off, and any niggly areas re-flowed. The end result was a studio built for musicians that had a control room big enough to fit 50 A&R guys, big windows, and the ergonomics of a Herman Miller chair.

It also had a live room that had a knack for delivering incredible drum sounds, just listen to the deep rumbling punch of the kit on INXS’ Never Tear Us Apart. In the early days SSL designer and tech at the Townhouse, Chris Jenkins, let them in on why his studio sounded like it did. “It used to be a stage where they shot those films with all the girls diving into a swimming pool, so it was built on top of an enormous concrete box,” recalled David. “People always think live rooms should be bright, but it’s the depth that gives them the sound. We spent a lot of time making sure our room had that bottom end. It was all wood and we had big resonators that reinforced the low end.” The other two elements that gave that big ’80s sound were ambient miking and digital reverbs. David: “Before that it was all that close-miked, Fleetwood Mac, West Coast sound. Ambient mics weren’t a thing, apart from Led Zeppelin who were really the instigators. It was also when digital reverbs first came out. We had the first Lexicon 224, and it just had that sound.”

SSL TOUCH DOWN

Now, of course, in those days you needed a console. They picked the SSL because they knew Jenkins, and felt more in tune with how UK studios, like the Townhouse and Olympic, were working at the time. At a quarter of a mil, it was a big risk, but you only take those sorts of risks if there’s a proportional upside. Even with such a big outlay, that upside was wilder than they could imagine. For the next decade, Rhinoceros was booked six months in advance — seven days a week, 365 days a year.

There was a career upside too. Because they were the only in-house engineers in Australia with an SSL to play with, they were also the only ones who knew how to operate it. David had previously only engineered demos on his friends Tascam Portastudio, and now he was in charge of one of the country’s biggest studios. It was a big leap, but David said engineering came quite naturally to him: “It always seemed quite logical. If you know what your endgame is, technology is just a tool. The end goal is to capture a performance as well as you possibly can, and usually, as clean as you possibly can. I always try and generate the sound at the source because performers react to what they’re hearing. We had really great producers come from overseas, so we watched and absorbed how they did it, and they all did it the way I imagined you would.”

Rhinoceros’ rooms and the SSL console attracted a high level of clientele, which benefitted two young Rhinoceros members in particular, David and Al Wright. For the next decade they tag teamed on Rhinoceros sessions, resulting in a collective discography that almost covers the history of the decade in Australian rock ’n’ roll: INXS, Noiseworks, Hoodoo Gurus, Australian Crawl, Models, Midnight Oil, Jimmy Barnes, GANGgajang, Mental As Anything — the list goes on. The first record Nicholas ever got an engineering credit on was INXS’ third album, Shabooh Shoobah, which ain’t a bad first job. Nicholas went on to engineer most of INXS’ catalogue, including the Chris Thomas-produced, Bob Clearmountain-mixed Kick. David was nominated for ARIA Engineer of the Year every year from 1987 to 1991, winning it twice in 1987 and 1990.

“I think I got on with a lot of those people, and ended up working on all of [producer] Chris Thomas’ records for eight years; because we had the same mindset on how records should be made,” he said. “It was also the commitment I learnt, that there should never be a technical excuse to have to do something again. People devalue performance now by being able to hit Apple+Z and do it 60 times. We were working with people that expected to only do it once or twice. There’s that story of Aretha Franklin coming in the studio and singing through the song, then the engineer says, ‘Okay we’re ready now.’ She replies, ‘I only ever sing it once,’ and walks out.

“Over 40 years, I’ve been an hour early for each session, ready and prepared. I always try to make the process as invisible as possible so all you’re thinking about is the music.”

GOOD OL’ DAYS END

With the studio pumping along, over the next 10 years David and Andrew filled the racks, bought pairs of every Neumann, two $80,000 Studer tape machines, and another SSL, this time costing $750,000. “It was a 5.5m-long E, the last of that series they made because they discovered the buses weren’t balanced,” said David. “You had to un-bus a whole lot of channels you weren’t using otherwise it got spongy. After that, they brought out the G.

“The console cost around $600,000 when we ordered it, but we had to pay for it when it landed. Andy and I were watching the television one night, when the Australian dollar crashed. We sat there with a calculator, and overnight our console went up almost $200,000 — so did our Mitsubishi tape machines. We ended up going half a million dollars over budget on the second studio.”

Rhinoceros blossomed because of the unequivocal local support for Australian music that spurred the industry on. “It was a really magic time for radio support,” said David. “We would mix a song and go up to Paul Homes at Triple M in the middle of the night and he’d play it on the radio. It didn’t have to be researched. If DJs liked it, they could play it. There was so much Australian music on the radio. Triple M was the catalyst for why the industry was so healthy in those days.

David said there was plenty of stereotypical ’80s excess too, it just happened after the day in the studio was done: “The culture was that everybody worked really hard — start at 10 o’clock in the morning and go until we’d reached our used-by date — then go out to our own bar in The Cross, let our hair down and get absolutely trashed. We were young, and didn’t need much sleep, so it would all start again on time the next day.

“There wasn’t a lot of excess in the actual studio until the very end of the ’80s, when it really got stupid. A lot of times the label A&R guys were the instigators; they would just use the studio to have a party.”

It was around that time that Rhinoceros’ dream run flamed out. The pair had sold off parts of the business over the years to finance the second studio. Being relatively naive musicians in a time when Wall Street corporate raiding was a buzz phrase, they never realised those previously minority shareholders could amalgamate their holdings into a controlling interest. It was right at the end of the ’80s, midway through the making of INXS’ X, when David and Andrew walked into Rhinoceros only to be told they no longer owned the business.

“I never really understood it because they didn’t know how to run a studio,” said David. “It was also bad timing because that’s when the music business turned down really sharply. In a year, Rhinoceros went from having both studios booked three months in advance to being empty, and we’d never been empty. I had to be restrained several times from burning the building down. We built it with our bare hands and it was our whole life. I was very bitter for a long time.”

The memories of Rhinoceros were too strong to handle. It wasn’t just the records. Inside that building sat the second SSL console they purchased; the one David commissioned with a monitor pot that ‘went to 11’. He paid a premium for it, and it was the first of its kind but would feature on every SSL thereafter. There was also the memory of first ever setting eyes on a strobe guitar tuner when Joe Walsh and Waddy Wachtel brought in a mystery box with spinning wheels.

Literally unable to be in the same country as the dead shell of his life’s work, Nicholas packed up his bags and took Chris Thomas up on his offer to follow him back to the UK.

As far as I’m aware, it was the first totally tapeless album ever released by a major label, and it was a nightmare

LONDON CALLING

On the way to London, David stopped over at Puk Studio in Denmark to engineer Elton John’s Sleeping with the Past for Thomas, the perfect tonic for such a bitter pill. Sitting on the plane, David kept mulling over the surreal turn in events and one question kept popping into his mind, “Am I good enough for this?” Slowly he turned the question over, until he remembered how it had never mattered before. Everyone questioned them about building Rhinoceros, and it was booked out for a decade. By avoiding the question, ‘What have you worked on before?’ the first record he ever engineered was a major one. He knew he had the ability, it just always came down to other people’s perception of him. After losing Rhinoceros that invincibility had taken a hit. “It was pretty scary, but I’ve always liked a challenge,” David reminded himself.

In the end, he was more prepared than he knew. All those years of dealing with one-take wonder singers like Michael Hutchence, had readied him for Elton. “Michael was more a performance kind of guy,” said David. “With Mediate, he walked in with a piece of paper and sang that whole vocal (which is a million words) in one take and went, ‘Thanks very much,’ then walked out.

“Elton was the same. He would write the song in the studio sitting at the piano with a bunch of drum beats and editing Bernie’s lyrics as he went. Then he would say, ‘Okay, I’m ready!’ and play it. After that, he would sing it three times as if he’d sung it his whole life and it would be perfect. Then he’d lie on the back couch and we’d spend the rest of the day making the song.”

It wasn’t to say the experience was entirely familiar, it was still eye-opening for a Surry Hills boy to be working with international musicians of that calibre in a field in the middle of Denmark. “The drummer, Jonathan ‘Sugarfoot’ Moffett — who used to drum for the Jackson Family, Michael Jackson and early Madonna — would come in from the field in his jodhpurs, listen to the song and play one take. It was bizarre.”

From there, David continued on to the UK, and one of the many records he engineered was Pulp’s Different Class. “The very first song we did was Common People, and it was a magic moment for them,” recalled David. “They used to be a folk band, but then they got a new bass player who had the same sort of intellect as Jarvis, and the lead guitarist who started the record ended up getting kicked out for the guitar tech who’d been replacing all his tracks at night time.

“Common People starts at 80bpm and ends up at 160, but none of it was done to a click. We had a magic end and magic front, but we were up till five trying to edit together the middle takes to get between the two. Then Jarvis put one acoustic guitar take over it and it glued it together.

“Jarvis reminded me a lot of Hutch, he was very connected to pop culture at the time and just new what was cool. Common People was a big hit, and that’s when Jarvis got up onstage at the Brit awards and disrupted the Michael Jackson concert. It was a British show and Michael got three quarters of the production budget; Oasis, Blur and Pulp got nothing. He ran onstage, pulled a bit of a brown eye, and the security were chasing him. It was like the keystone cops, guys are running after him and they’re silhouetted against the backdrop. Jarvis got arrested — he bumped into one of the kids in the choir, and they tried to get him for assault but eventually let it go.”

Throughout the ’90s, David was based in London, but worked throughout Europe and the US with artists as diverse as Ash, Soul Asylum, Marcella Detroit, Heroes Del Silencio and Johnny and David Hallyday. He achieved numerous No. 1’s as a mix engineer for UK producers Chris Thomas, Chris Kimsey and Phil Manzenera, and French producer Pierre Jaconelli.

THE THREE MUSKETEERS

David’s ‘craziest session ever’ has to be the time he played D’Artagnon to Rod Stewart, Sting and Bryan Adams. Trying to assemble the three musketeers to track All for Love was almost impossible. Bryan Adams was the linchpin of the deal, having written the song, and he was adamant about singing in the same room as the other vocalists. Unfortunately, Rod Stewart couldn’t make it back to the UK. So after recording Sting and Bryan and the drums at Air Studios, they got on a plane to record Stewart and landed in LA the same day they’d left, then finished the session and flew straight on to Adams’ studio in Vancouver. “It was all over the space of 10 days,” said David. “We didn’t sleep for the first three days, we just went from one session to another.

“Because Bryan insisted on singing with the other artists, we had two tracks of every take. We spent a week up at Bryan’s place in Vancouver comp’ing hundreds of vocal takes, because everything was pairs. We had two 48-track Sony DASH machines full of vocals and a mix of the track. We had two of everybody singing the whole song multiple times so it was just the most incredible headf**k.”

David’s not a huge Bryan Adams fan, he was in it more for Sting and Stewart, but he didn’t talk much to either — Stewart never even made it into the control room. He did get to have one star struck moment though: “One of the bands that really had a huge influence on my life was Little Feat, and Bill Payne was playing piano on the record. When I was 16 or 17, I remember listening to Feats Don’t Fail Me Now driving down the coast to go surfing. It was a pivotal moment in my upbringing. I got really pissed with him in his hotel room. It was one of those few times I’ve been a total groupie.

“It was my first U.S. No. 1 as a producer, and an absolutely mad 10 days.”

We would mix a song and go up to Paul Homes at Triple M in the middle of the night and he’d play it on the radio. It didn’t have to be researched. If DJs liked it, they could play it

ATES WITH EARLY DIGITAL

Another strange session, this time of a self-inflicted nature, was the occasion he and Matt Vaughan co-produced Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s Universal, and thought it would be interesting to make a tapeless album. One of, if not, the first. Not the first digital album, mind you, but completely tapeless. Rhinoceros had already taken the plunge with digital in the ’80s, bringing in an Otari 32-track digital tape machine to record Kick. “With analogue tape you had crosstalk, you had to be really careful about what you recorded on adjacent tracks, and every time you bounced you’d have regeneration loss,” said David. “Over the course of a record, the drums never sounded as good as the first week or so. As an engineer, a digital machine was this magic box. I could bounce things endlessly, put the vocal next to the bass drum, and nothing was lost. All the restrictions disappeared. With digital it was like I had a word processor — I could chop, edit and move things around without losing any quality.”

He would end up being a little less enthusiastic about the state of tapeless digital. Stability was a state that hadn’t quite been reached. The tipping point was when Andy McCluskey from OMD arrived and had all the songs already written on Logic. They just decided to go all in with it.

Matt had worked as a programmer for David and Chris Thomas on a lot of records, so he was already proficient with Logic and had bought himself 16 channels of 16-bit/44.1k Pro Tools running on a Power Mac. Just to be sure they’d stick with it, David and Matt took some precautions to deter them from trusting their better judgement. “We actually got the studio to take the tape machines out so we wouldn’t be tempted,” said David. “We didn’t even back up to them, because we knew we’d end up using them if we did. We had some absolute disasters. Pro Tools was very unstable; we’d lose songs because they wouldn’t start up again, and we’d have to spend hours reassembling them from audio files. It was torturous, but we stuck to our guns.

“This was when a 250MB hard drive would cost you a fortune, and they weren’t that robust. We had to keep copying them because they’d get fragmented. We went digital all the way, it wasn’t even mixed to half-inch. As far as I’m aware, it was the first totally tapeless album ever released by a major label, and it was a nightmare.”

PRODIGAL SON RETURNS

David moved back to Australia in 2000, and things have changed a lot since the Rhinoceros days. For one, everything he’s done since then has been in Pro Tools. He still records to tape every now and again, when he can find a machine that’s been maintained, but always transfers back into the DAW. “We did the George record on two-inch before bouncing it,” said David. That was Polyserena the platinum No. 1 record David produced in 2002. He also produced the No. 1 album Silencer for New Zealand band Zed, and won ARIA Producer of the Year for the Drag album The Way Out in 2005.

David’s still active today, though he doesn’t have a fixed studio address. As good as the ’80s were to him, he couldn’t imagine owning a studio again. Besides, these days, most of what he needs can be found in two pieces of gear — a laptop and his Szikla Prodigal. It’s a hardware unit that David developed with Andy Szikla, pulling together two channels of everything an engineer needs to record most things. Who knows, it could be David’s next big contribution to the Australian music industry.

RESPONSES