Life on the Ground

The Pilot Episode. What the hell is a ‘Producer’ and is an ‘Engineer’ capable of building bridges? It’s all ‘Clown Science’ to some…

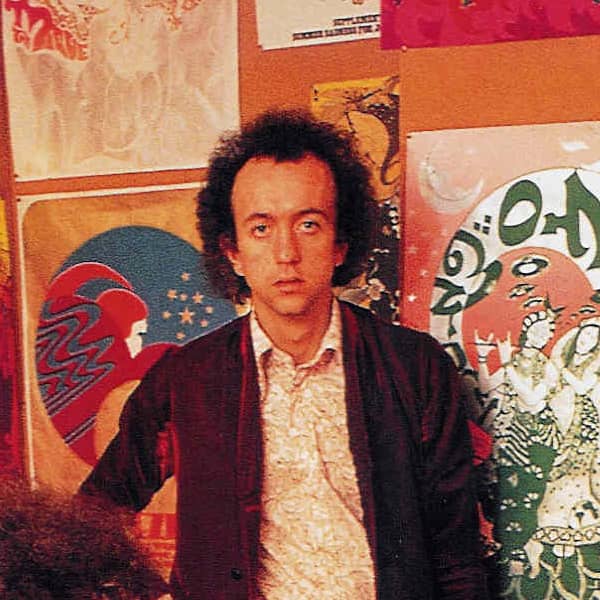

Jonathan Burnside (above) has produced and engineered albums in both the USA and Australia, for the likes of The Living End, The Sleepy Jackson and Faith No More, amongst countless others. He now resides in Melbourne and owns and runs Eastern Bloc Studios (formerly Altantis) in Hawthorn. AT welcomes him aboard.

Hello dear reader and welcome to the first episode of Life On the Ground, a tragic situation comedy detailing the high hopes and changing tides aboard a leaky boat, the HMAS Recording Studio. Battered on the reefs of sinking record company budgets, sails torn by the howling winds of cheap digital technology and rising real estate prices, torpedoed by U-Boats full of novice bedroom recordists and cannon-balled by wanton music piracy, still the little ship sails on through the dark waters of a shark-infested Music Industry.

What madness motivates this screwball crew of sonic thrill-seekers to brave unscrupulous music pirates, savagely deaf A&R people and drunken band managers with tin ears who teeter about on wooden legs, chanting “Work for cheap, you scurvy dogs, work for cheap! Maybe we’ll throw you an album project some day. Yarrrrghhhhh!”? Will we hear the captain once again thunder the immortal words; “Aye, your face looks honest… but I can’t put it in me cash register,” as yet another band tries to avoid walking the Plank of Full Payment by desperately singing sea shanties about a big break waiting like buried treasure at the next port of call? Will the intrepid crew ever see the sunlight outside of the control room galley and finally get exercise other than viciously hammering on computer keyboards and repeatedly performing 375ml elbow curls?

JUST WHAT THE HELL IS IT WE DO FOR A LIVING?

Twenty years on and it’s still not easy explaining exactly what I do for a living. My mother-in-law had a few interesting ideas on the subject when my wife and I were first dating. Sometimes she’d say, “What does he do? Is he a clown?” Other times she’d have the notion I was a scientist, maybe because of my glasses. I could fully understand her confusion. So is this ‘Clown Scientist’ idea as accurate as the Producer, Engineer or Mixer credits that are usually given? Perhaps. I do think it has more panache about it, that’s for sure.

There have been plenty of pranks and pratfalls in studios all over the world for years; people trying to provide comic relief during some insane moments or sometimes just succumbing to surreal fits of hysteria as the intensely long hours involved in making an album roll on. There’s also a certain amount of science – albeit simple – involved in studio work: a bit of the old phase relationships, acoustical theory, alignment procedures, schematic reading, and mastering the creation of a proper cup of tea. It’s hardly the stuff of a Newton, an Einstein or a Hawkins but it’s still science… to clowns anyway.

All this got me thinking about whether I should really be called an Engineer at all. Maybe it’s a bit too much of a stretch. Sure, I can record a bridge but can I design or build one? Maybe I should stop accepting this ‘Engineer’ credit altogether and just call myself a Recordist. I still prefer Clown Scientist but I’m willing to give a bit on this one, especially because Scientist just doesn’t sound very rock ‘n’ roll and Clown might make clients a bit nervous about shaking my hand, fearing what may lie hidden in my palm. From this day forward I’ll do my damnedest to ensure I never receive an ‘Engineer’ credit on another album. That way I won’t ever again have to say: “No, no, I’m not a real engineer, I’m a music engineer!”

BUILDING BRIDGES (& CHORUSES)

Anyone with an M-Box and a Chinese condenser microphone can call themselves an Engineer these days but that’s a long way from Real Engineering, which is doing jobs like designing a jumbo jet or the West Gate Bridge (okay, the West Gate Bridge might not be the best example because it tragically collapsed while still under construction. But maybe that was because a Second Engineer designed it).

One caveat: I’m keeping the Engineer credit in the space on my passport where ‘Occupation’ is listed. Previously, I had foolishly listed Music Producer as my occupation but soon got tired of being hauled in front of packs of drug-sniffing beagles at every border crossing. Now that the passport controllers of the world think I’m a Real Engineer, they’ve called off the dogs and stopped inquiring about how I plan to support myself while staying in their country.

ROOM FULL OF PRODUCE

So I have finally realised that I don’t actually Engineer for a living, even though I’ve been credited with it for years. Maybe my Producer’s credit is a safe enough one though. A Producer is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as “a person generally responsible for the production of a film, a play or a broadcast program, album, etc.”.

Still, what do I say when I’m asked, “Exactly what is it a Producer does? Looking at working methods of some of my favourite Producers has not made answering that question any easier. George Martin, arguably the most well known Producer since the music industry started issuing this credit, is probably the best example of the Classic Producer. As was quite standard in his day, he also worked in an A&R capacity for a single record company, EMI. He decided if artists had sales potential and if so, he would sign them to the label and supervise their recordings.

As his relationship with The Beatles – his most famous signing – developed, and as their music grew more intricate, he would write many of their memorable string arrangements for them, being a trained musician and a master of music theory himself. Martin certainly brought polish and sophistication to The Beatles’ sound, as well as making brilliant pop arrangement suggestions such as starting a song with the chorus instead of the verse.

He kept things well organised and acted as an anchor in an increasingly psychedelic sea of ideas. He may actually have been the first Producer to welcome the musicians into “his” control room, and as The Beatles’ studio savvy increased he’d often leave them to work with Abbey Road staffers while he enjoyed evenings at home. (Possibly involving the musicians in production was a ploy to get a few evenings at home. What a clever man!)

His role as a Producer contrasts completely with someone like the late Guy Stevens, an incredibly influential figure on the British scene during many of its best years but now largely forgotten and sadly under-credited. Stevens was originally a DJ at the New Scene Club in London during the mid ’60s where he introduced bands like The Who and The Small Faces to Jamaican dance music, American soul and R&B. This can be heard on his friends’, The Rolling Stones, Sweet Black Angel from Exile on Main Street. He titled the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album and named the band Procol Harum after his cat. Like George Martin, Guy Stevens worked for a record company, Island, during some of his career but the similarity stops there. His duties at Island included going to countless shows to spot new talent, rolling an endless supply of spliffs for whoever came through the Island offices and finding the best of obscure music from the West Indies and America to release on Islands’ Sue Records label.

He was more of a trendsetter and a taste-meister than a musical arranger and he often repainted the young bands he produced with heavy-handed, broad brushstrokes, many of which turned out to be strokes of genius. Deciding he should pair a loud rock band with a Bob Dylan-sounding vocalist, he found a hard rock band called Silence, renamed it Mott the Hoople (the title of a book about circus freaks he had read while in prison for a drug offence), demoted their lead singer to roadie and found Ian Hunter to be his ‘Dylan’. Along with T-Rex and David Bowie, the band defined the British glam era of the following years. Hunter later said that Stevens saw a spark in him that he did not even see in himself and without Stevens; he’d still be working his factory job.

CLASH OF CULTURES

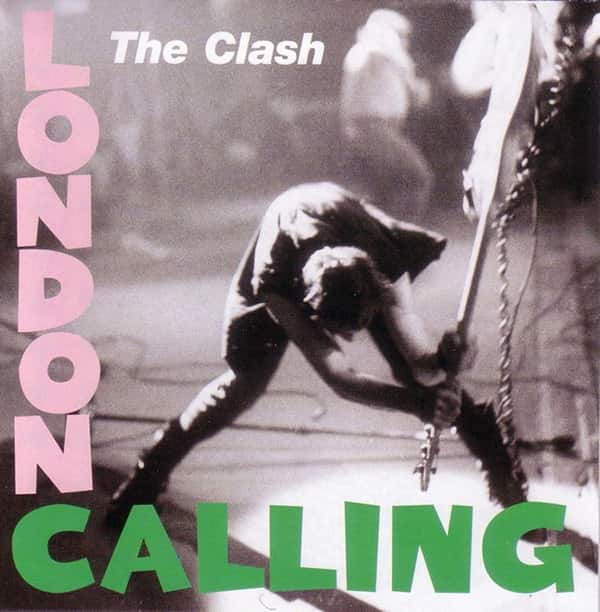

Ten years and several drug-busts later, The Clash called on Stevens to produce their seminal London Calling album. In an effort to get bigger guitars than those on their brilliant but somewhat weedy-sounding first album, they had enlisted Blue Oyster Cult guru, Sandy Pearlman, to produce their aptly titled second album, Give ‘Em Enough Rope. The guitars certainly sounded bigger but it was a terrible pairing between a Producer and a band, Pearlman’s anal-retentive do-it-a-hundred-times style of working robbing The Clash of their greatest strengths of urgency and attitude. The results bring to mind the joke that goes: “It was a successful operation but the patient died.”

The Clash knew what musical influences Guy Stevens had brought to the UK scene preceding them and they wanted these influences brought to the fore of their new album after their American hard rocker disaster. Stevens’ now industry-outsider status and wild man reputation suited them fine and his penchant for verbally abusing and even punching singers to get a more emotive performance from them seems to have worked perfectly for Joe Strummer.

Sure, I can record a bridge but can I design or build one? Maybe I should stop accepting this ‘Engineer’ credit altogether and just call myself a Recordist.

PRODUCING WHATEVER

So is a successful Producer a formally trained musical arranger who works hand-in-hand with the big boys at the record company head office? Or is he or she a confrontational, controversial spliff-rolling culture vulture who brainstorms new musical angles and uses cheap psychological tricks to get a performance up to their emotional standards? The correct answers are: both, either, neither and whatever…

It’s just a hunch, but I can’t believe that Paul McCartney would have taken being wrestled to the ground by George Martin in his stride when he was singing Yesterday, or any song, for that matter. George Harrison probably would have jumped on the first flight back to the ashram, and John Lennon, the most aggro hippie the world has ever known, might have kicked poor Martin down the steep flight of stairs between the control room and the studio room at Abbey Road. I’m also guessing, and probably not wildly, that Joe Strummer would have been completely disappointed if Guy Stevens had shown up at the studio at 9am sharp, dressed nicely in a starched white shirt and black tie, smiling and saying, “Here’s the string arrangement I just wrote for Death or Glory.” But he was fine with the times Stevens trashed the studio and lay down in the path of the head of the record company’s limo.

A Producer does… whatever. How’s that for a job description? And ‘whatever’ means whatever it takes; whatever it takes to get the recordings to be of a higher level artistically (or sometimes solely commercially) than any of the people present could have achieved without that unique team in place. It means whatever skills, personality traits, musical knowledge, listening background, life experiences and psychological approaches the Producer can bring to the studio. It means whatever instinctive or studied understanding of the artist the Producer can use to judge the most effective approach he or she should utilise during the moment at hand. ‘Whatever’ means watching the clock, because studio time is seldom unlimited, and at the same time being as much as possible in the moment at hand. It means being responsible for the budget and still trying to find ways to not sell the project short. It means that even if the band isn’t great, whatever. It’s still the Producer’s job to make them suck less.

Now here’s some sticky point pudding:

What is a Producer’s role when the artists credit themselves as Producers and the album is exactly what they have played live for the previous year, only without the crowd chatter, the smell of stale beer and the remote possibility of meeting someone interesting at the bar? I guess maybe the decision to keep a Producer out of the studio was such a big one that they may have believed that this, in itself, constituted Production. What’s even more confusing is the album that sounds exactly like the way the band has been playing the songs live before they went in the studio, but the album has an outside Producer credited on it. Maybe that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” adage the Producer brought to the studio was enough to earn the cash and the credit. Whatever. Or perhaps the Producer simply drove them on to the point that they obtained the level of truthfulness that they’ve pulled off live, which is not always easy to reach in studios because many musicians find them sterile, vibe-killing environments. None of this brings me any closer to describing what a Producer actual does as it depends so much on the people involved, the moment in time being captured and the environment it all took place in. Next time I’m asked, I’ll stick to my usual answer: “You’d have to be there…”

MORE THAN JUST A BALLOON TWIRLER

Another part of my job description, according to album credits, is Mixer. That used to be fairly cut and dried, especially when Mixers were called Balance Engineers. The task during that period was to balance the instruments on a very limited number of tracks, some of which may have already been mixed together during reduction bounces, and reduce them to a mono or stereo mix. With modern digital productions, mixing has changed dramatically. The increase in the power of computers and of ProTools (and like platforms) mean that it’s not so unusual to do mixes that have 50 or perhaps over 100 individual tracks. My ProTools HD2 rig in my Mac Eight Core can play back 192 tracks simultaneously and a single song can contain up to 256 tracks. This can make a Mixers’ life a little scary.

So much about a modern music production hangs on the quality of the mix. The entire flavour and outcome of a song can be dictated by the approach taken, decisions made and aesthetics embraced during this often complex process. A successful artist manager once said to me: “I’m not certain if someone can mix a song into a Top 10 hit but I know a song can be mixed out of being a hit.”

Modern mixing has reached a point of such importance, and mix technology has reached a level of such power and possibilities, that mixing now constitutes a type of co-producing in some cases. It’s a grey area sometimes and on many projects, mixing can still be fairly straight ahead. But the fact that major label mixers are often given a production point on a project’s sales certainly adds weight to the argument of the Mixer as a type of Co-Producer.

Sometimes when I’m mixing, I suggest edits that may include shortening or lengthening the song or I create parts or sections and counterpoints by moving existing elements around to different places in the song. Many times I’ll turn elements off in certain sections to create greater dynamics in the song. Sometimes that’s been as drastic as muting the drums during most of the song. I may add elements during the mixing process, especially if it’s an album I’ve produced. A counter melody, additional harmonies, percussion or a held note through a section might come to mind once the mix has taken a near finalised form. The line between a mixing session and a tracking session can be rather elastic in nature. I prefer having at least some members of the band around the studio while I mix so that we can play ideas off each other, and I won’t have to second-guess whether they’ll like any changes made to the song. Of course, on some albums, mixing is not like this at all. I simply have to make everything louder than everything else and then all band members are happy.

Even defining what I do as a Mixer is not easy because it changes from album to album. Next time I’m asked, I think I’ll answer with a question: “A mixer? Fancy a cocktail, anyone?”

Jonathan Burnside can be contacted at: [email protected]

RESPONSES