Led Zeppelin Live

Led Zeppelin proved they still have what it takes to rock an arena in their first full concert since John Bonham’s death in 1980. AT goes behind the consoles with live sound leviathan, ‘Big’ Mick Hughes.

Text: Jonathan Miller

It was September 12, 2007 when the bombshell dropped. UK über-promoter, Harvey Goldsmith, convened the press to announce that Led Zeppelin would headline a tribute concert for the late Ahmet Ertegun – Atlantic Records founder and mentor to some of popular music’s greatest names. Profits from the gig would go to an Ertegun-established charity.

The music world went into a flat spin – reunion gigs hardly come any bigger than this. And what happened next was a phenomenon of modern-day concert promotion: the concert would be staged at London’s 02 Arena; 20,000 tickets would be available; tickets would be priced at £125 (A$275) apiece; and you had to enter a ballot to express interest in purchasing tickets (two per household).

Predictably, perhaps, the website exceeded its bandwidth allowance and crashed almost immediately following the announcement; as it was, overwhelming demand proved to be something of an understatement here as it received an amazing one billion page impressions with – depending on whose estimate is to be believed – somewhere between 20 million and 200 million people attempting to avail themselves of those tickets. According to one source: “… a 25-year-old Scottish man was rumoured to have paid $170,000 for a pair at a charity auction.”

Behind the scenes no less serious negotiations were going on to decide who would mix the show. At front of house would be a Midas XL8 Live Performance System provided by Britannia Row, with two engineers at the controls: ‘Big’ Mick Hughes mixed the band – Jimmy Page on guitar, John Paul Jones on bass and drummer Jason Bonham, while Robert Plant’s front of house engineer Roy Williams handled the singer’s soaring vocal range.

After decades mixing Metallica, ‘Big’ Mick Hughes is well accustomed to the big occasion but come the night before showtime, even the unflappable Mick was still feeling the pressure to perform. “It’s very difficult to just go in for a one-off,” he reasons. “I’ve never done a show as stressful as that, and I’ve done some pretty big shows – a million people in Moscow [with Metallica] wasn’t as stressful as doing this thing! Even just standing outside my hotel the night before I found myself chatting to some guy… I think he said his ticket was either five or 10 grand! I’ve been talking to lots of people who’ve paid this kind of money… it was more than just a show. It was a spectacle.”

ONE CONSOLE, TWO OPERATORS

The road to staging the spectacle was long and tortuous. Hughes explains how he landed the gig: “… I met and had a word with Qprime – the management company I work with for Metallica, who also manage Jimmy Page. Jimmy had been to see Metallica at Wembley Stadium (on July 8, 2007), and thought it sounded good, so that gave me the ‘in’ there.”

Interestingly, Metallica’s Sick Of The Studio ’07 tour just happened to be the first time that Midas ‘evangelist’ Hughes had taken the new XL8 console on the road, so it’s little wonder that the same console ended up being used with Page & Co once Hughes’ well-tuned ears had been brought to bear on resurrecting that legendary Led Zeppelin sound onstage – not least that its inherent flexibility allowed him to work alongside Williams without needing a second FOH console. “It was perfect,” Hughes notes, before revealing: “In all fairness, I did an analogue spec at first – XL4, obviously… gates and various compressors for different jobs; effects were a bit of an unknown quantity at that stage – obviously, there’d be the mandatory reverb machines, but I didn’t know if we’d need anything special. It turned out that we needed flangers and phasers, plus a plethora of different reverbs and stuff, so it’s a good job we didn’t go that way [analogue], because it pretty much all changed. I ended up with probably nigh on 70 input channels – admittedly, only 34 or 36 of those was the band, and the rest were effects returns, but it just swelled sideways. Fortunately, with the flexibility of the XL8, it wasn’t suddenly a case of, ‘Oh, shit; we need to get another desk!’ The XL8 came into its own when everything was changed around – we could literally just re-program the effects rack, for example.

“Of course, being able to recall a pop group into the ‘B’ area on the console meant that we could set the end bay of the console to be Robert’s vocal and his effects returns, so Roy could have his own pop group at the end while I used the rest of the console with the VCAs to do the band.”

This unusual way of working begs the rather obvious question that Hughes himself brings up when addressing that potentially divisive two-man operational issue: “I’ve known Roy for probably 20-25 years, and people keep asking, ‘What’s it like to have dual engineers?’. But because I’ve known Roy for so long, I know what he’s done, and he knows what I’ve done, so there was none of that chicken strutting scenario. I had nothing to prove to Roy, and he had nothing to prove to me. We were there to do a job, and we both just got on with it together. We never once argued about it.”

RESURRECTING THE ’70s

While Williams and Hughes were clearly committed to making their console-based marriage work for the benefit of all, not least Led Zeppelin, ironically it was actually that elusive Led Zeppelin ‘sound’ that was to prove problematic for Hughes: “That was the one question that created a big dilemma; were we talking about the 1970s or 2007? At the start, I really didn’t know which way it should go. I listened to loads of bootlegs and I listened to the albums and without a doubt the band had a unique sound, but I think some of that sound was thrust upon them by the period in which it was recorded – the limitations of what equipment could do. So it begged the question: what does Led Zeppelin sound like now?”

What to do? Well, Hughes did what he could, striking up a direct dialogue with the band: “We talked about it, but when you’re so close to the wood, can you see the trees? I don’t know if they really had a vision for how they should play out. We played around with lots of different sounds and stuff in rehearsals, trying out different techniques – alien to me, some of them. I come from a world where it’s all close miked, and everything’s gated and tidy; it works, and that’s how we keep the big arena and stadium sounds clean. Then, all of a sudden, you’re into another world with Led Zeppelin, because you’re into a more ambient sound.”

Little wonder, then, that Hughes admits to feeling some pressure! “I was in a lose-lose situation, because literally everybody has an opinion on how Led Zeppelin should sound,” he reasons. “It’s very difficult to mix something when you haven’t got the picture firmly inside your head as to what it should sound like because you keep getting pulled in different directions by everybody’s attitude to it. In the end, we decided that this had to be ‘Led Zeppelin with technology’; had Led Zeppelin continued to play for the last 27-odd years, then this is really the point at which they would have come to.”

I was in a lose-lose situation, because literally everybody has an opinion on how Led Zeppelin should sound

OUT ON YOUR EAR

That said, in-ear monitoring was out of the question. “They’re not interested in any of that kind of stuff,” states Hughes, humorously adding: “That part of the plot was still pretty 1970s.” On the night, monitor engineer Dee Miller mixed on a Midas Heritage 3000, and specified a Turbosound system comprising 11 TFM-350 high-powered, full-range wedges (incorporating twin 15-inch drivers and a two-inch compression driver in a 42° angled enclosure) for general stage coverage; a pair of TFM-450 bi-amped wedge monitors (featuring a custom 15-inch neodymium LF driver and a three-inch diaphragm neodymium HF compression driver on a 40° x 60° horn) for Page; another pair of TFM-350s for Bonham; plus six Flashlight mid-highs per side for sidefills.

THE SONG REMAINS THE SAME?

Little was being left to chance, so back in July last year Hughes found himself getting up close and personal with Led Zeppelin on a rehearsal stage for the first time, within West London’s Black Island Studios, the band having already had “a little knock” in June to find out if they could still play together before they actually got everybody’s hopes up.

Initially listening back via two crystal clear Genelec 1037 active three-way monitors at Black Island, and armed with his trusty Midas XL8 and an accompanying Klark Teknik DN9696 AES50 Multitrack Recorder well in advance of its official release, Hughes set about perfecting those Led Zeppelin sounds, paying particular attention to recreating John Bonham’s distinctive drums, one of the band’s unmistakable trademarks.

Bonham Snr’s pounding drum part recorded in a three-story stairwell, which opens When The Levee Breaks (from 1971’s Led Zeppelin IV album) remains one of the most sampled drum breaks of all time. “I tried gates on the toms at the start, and completely failed,” freely confesses Hughes. “I tried using external triggers taped to each shell to fire the gates; that kind of worked, but it sort of failed, because at some point you would hear a gate. It became pretty apparent that I would have to do it with no gates, so eventually the gates got the heave ho. Then it was simply a case of working with the overspill of all the different drum mics and stuff; again, that’s where the XL8 came into its own, because we had the new 9696 recorder – the SADiE one that they’ve conjured up for virtual sound-checking [see last issue’s news for more detail – Ed.].”

Here Hughes’ equipment of choice was very much screaming ‘2007’. “It was taken way out of context to what it was designed for,” says Hughes elaborating on the 9696. “Fortunately, it behaves very like a DAW, insomuch as you can zoom in on the waveforms, so it gave us the opportunity to whack the snare and look at the screen to see how long it actually took before the snare arrived back at the overheads and different tom mics. And because the XL8 has a delay on every channel I could actually delay the drum channels: taking the ambient mics as the zero reference, I had four milliseconds delay on the close snare drum sound, for example.”

The result?

“It made it so much fatter; you didn’t get all the phase cancellation,” reports Hughes. “We then did the same thing with the tom-toms; they obviously had varying degrees of delay as well, but we’re only talking milliseconds here – it’s not like we’re taking a snare and putting it in the next song!”

And the drum mics?

“Predominantly, the drum kit was miked with Earthworks. I had two pairs of overheads – the additional pair being quite high. The X-Y stereo pair consisted of two SR25s; the two overheads we used were SR25s. The hi-hat was an SR30, snare bottom was an SR25 and the snare top was a Shure SM57. I had an SR25 on the kick drum, which went into a KickPad to tailor the microphone to a kick drum sound. I also used another KickPad on the Shure Beta 52 that we had in the hole of the kick drum [the KickPad from Earthworks is a passive pad/EQ processor – just plug any cardioid kick drum mic into it, then out of the KickPad to your stagebox – Ed.]. The ride cymbal mic was a PC30, which is a little gooseneck affair we could sneak under the bell. The timpani was another SR30; meanwhile the tom mics were Audio-Technica 350s, which are also gooseneck mics.”

There you have it: instant Led Zeppelin drums. No need for samples; no sir: “I could have gated everything down; we could have even brought in some sampled drum sounds – fired some off the albums, even, but that would have been going for perfection, and I don’t think it’s about that. Led Zeppelin is an attitude more than a sound. The dynamics within the songs are fantastic, which is why you could never use gates… for the simple reason that the band will take it down to next to nothing and then they’ll build it right back up again within each song. The sound had to be open and have this airiness about it – kind of a melting pot.”

…it begged the question: ‘what does Led Zeppelin sound like now?’

WORKING THE ROOM

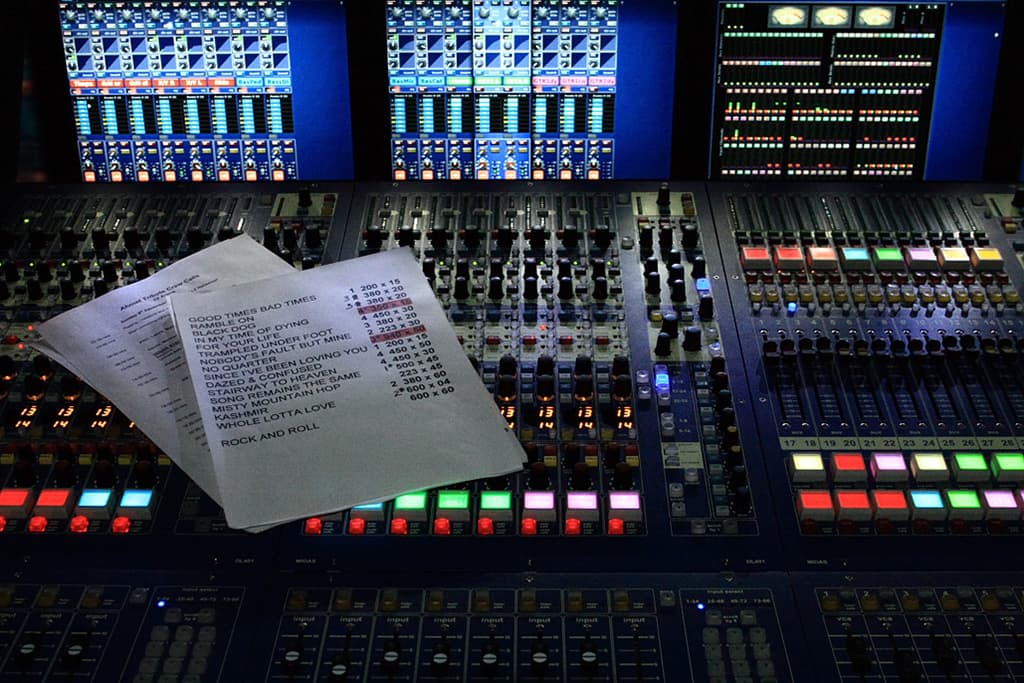

Following a week’s worth of “trial and error” at Black Island Studios without any PA gear (and, amazingly, without Robert Plant, who was otherwise engaged in America with Roy Williams), production stepped up a gear when Plant (and Williams) regrouped with Bonham Jnr, Jones, and Page (and Hughes) at a larger sound stage within Shepperton Studios with a ‘cut-down’ PA comprising seven Meyer Sound MILO per side, four flown subs, plus a couple of ground-stacked subs for a few run-throughs of the 16-song set before moving on to the final destination.

Shepperton, too, was far from an easy ride for Hughes. “All of a sudden, you’ve come off Genelecs and gone through a PA system, so there’s a transitional thing there, because suddenly you’re listening to PA boxes, as opposed to something that’s designed to be a studio monitor. We made a few tweaks there, but it was still a slimmed-down system; we couldn’t commit completely to stuff, because it was going to change again.

“Then we got into the O2 with the full-blown rig,” continues Hughes – full blown being an amazingly powerful all-Meyer sound system supplied by UK-based sound rental company Major Tom, upping the ante with 72 high-flying MILOs, plus a centre hang of six MICA compact elements, with 10 flown 700-HP subs per side; nine more ground-stacked 700-HPs per side; four more MICAs per side for outfill; and another MICA per side alongside eight UPA-1Ps strung across the stage for frontfills.

Three Galileo Loudspeaker Management Systems handled 36 outputs and Meyer Sound’s Director of European Technical Support, Luke Jenks, used a SIM 3 Audio Analyzer System to tune the system to work with the O2 Arena. And London’s much-vaunted O2 should sound stunning, surely? Over to O2 first-timer Hughes for the verdict: “Was I pleased with it? It’s not as easy as I thought it was going to be. I’d kind of believed people when they said that the room was going to be just stunning, and it wasn’t quite like that. It kind of sneaked up on me a little bit, which was why I had to do a bit of scrambling and juggling for the first three songs to make it fit.”

ON THE NIGHT

And as for the aforementioned dual-mixing scenario, was it alright on the night? “Even though we knew Jimmy would be doing guitar solos and stuff, the plan was to keep the vocal pretty prevalent,” Hughes reveals. “The vocal effects were really down to what Roy wanted to do, so it was his bag. There were quite a lot of effects on the voice – if Roy was doing a long delay, Robert tends to go and stand by the drum kit, so I did have a couple of repeats coming through when the drums caught the echo or something.”

So, job done, how does Hughes feel about it all after the momentous event? “Mmm,” he muses, and then pauses. “The reason I go ‘Mmm’ to that question, is because people always ask me, ‘What did it sound like?’ Well, you can’t really ask me that, because it’s in the ear of the beholder. Everybody has his or her own idea, but I think it sounded great! As well as being a great rock band, they were always a really ambient band with some real twists, and I wanted to try and capture that.”

With post-O2 rumours of a possible Led Zeppelin tour spreading like wildfire, would Hughes consider taking up the mixing mantle again? “As much as Led Zeppelin is probably the coolest gig to do right now, Metallica are my guys. If it comes to it, and they came and asked me, then I’d consider it; but, from what I’ve heard all along, this was a one-off.”

RESPONSES