Inside The Odditorium

The Dandy Warhol’s have ‘settled down’ into their bastion of creative independence — The Odditorium. But to keep from getting complacent on their eighth studio album This Machine, they instituted a single rule. Drummer Brent De Boer and engineer Jeremy Sherrer explain.

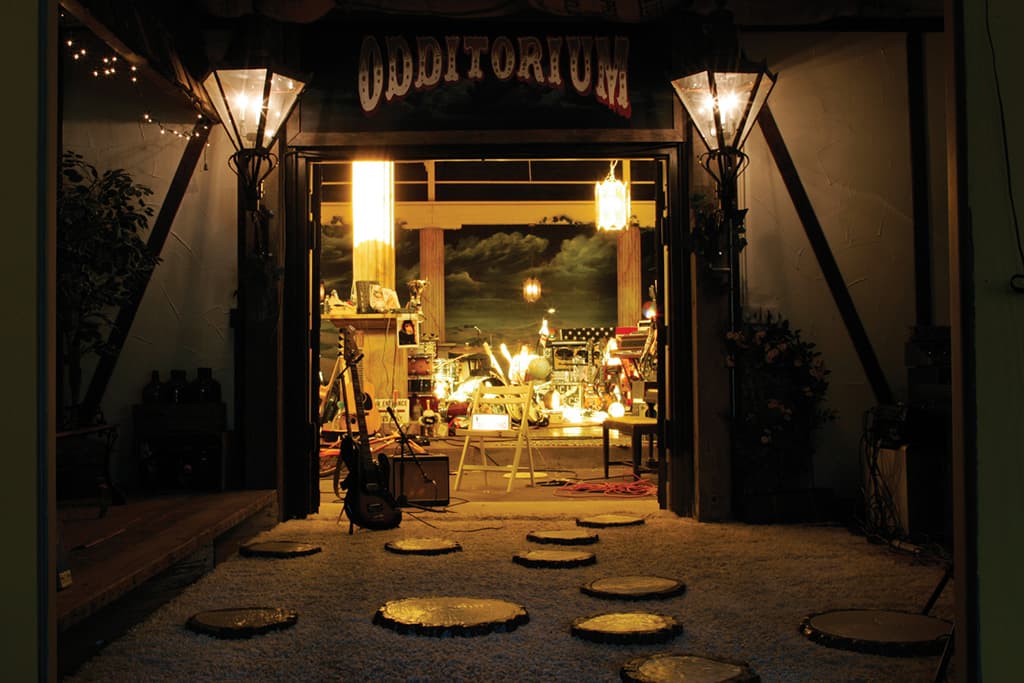

The Dandy Warhols have always stationed themselves at the confluence of creative independence and the mainstream. They used the cash from commercial advertising publishing to buy up a quarter of a city block in Portland, Oregon, that they made over as an emblem of their independence: The Odditorium. Modelled in the style of Andy Warhol’s Factory, it’s a band clubhouse, studio, stage, bar, video set, and giant chess set, wrapped in psychedelic trim.

Dandy Warhols drummer Brent ‘Fathead’ De Boer said it was the logical next step for the band to set up their own base outside the typical studio network: “We used to always rent a place that was not a studio — once it was an office building, while for Thirteen Tales From Urban Bohemia it was an exercise facility. We would just rent a room, load all of our gear in, set it up and make it work as our own studio. It turned out to be a lot more fun. Plus it’s nice to have the keys to the place yourself, instead of having to call the studio manager, and pay ridiculous amounts of money to rent a studio. We found that we get more interesting sounds from odd locations than making some professional-style, normal sounding record.

“We were successful that way. So we’d always been keeping an eye out for a permanent location and finally had enough funds saved up to go for it. So we bought this old machine shop in North-West Portland — it’s a quarter of the whole city block.”

THE ODDITORIUM

The Odditorium has one large live space, a control room, a dining room, kitchen, office area, video editing room, a green screen, a few isolation rooms, and some other fun areas. Like a human-sized chessboard made from 20,000 gallons of poured and stained concrete, a basketball court, a bar right in the middle of it all called ‘Best Bar’, a rooftop patio and BBQ area, and a full stage to rehearse on. “We thought we’d have gigs there,” said De Boer. “But we’ve only had a few private parties.

“There are two rows of yellow-tinted skylights that give the room a yellow hue during the day. And we have a friend who painted a mural of sand dunes and clouds around the entire outside of the big room and split the room in half by hanging a giant, gold curtain. There’s a jukebox, pool table, and giant church pew around that area. It has iron columns holding the roof up, so we removed the centre one and brought in a giant I-beam to hold the ceiling up where the chess board is. Then we wrapped the columns in this plastic material that looks like Roman columns and had that painted in faux marble, and we have the stage painted that way too so it looks like Roman ruins in the desert somewhere.

It’s pretty cool!”

The Dandys weren’t concerned about any negative effects ‘settling down’ might have on their creativity, they were just glad to finally have a club house. In functional terms, it’s like an office for rock ’n’ rollers. There are no showers, no beds, so no one can live there. Instead of wiring networks and phone lines like a conventional office might, they cut troughs, and re-cemented over a network of underground audio cabling so you can run mics in any room, for any flavour.

“There’s really dead, isolated rooms and there’s really huge basements,” said De Boer. “The main room is like a giant reverb chamber. And it’s really an ongoing project. We’re constantly adjusting and moving things and experimenting with different setups. The board’s moved to a second room now so that’s changed the whole dynamics of the studio. It’s such a massive space, you can endlessly experiment.”

FISHING OUT A SOUND

Engineer Jeremy Sherrer is credited with co-producing This Machine, and after bonding with vocalist Courtney Taylor-Taylor over The Fall seven years ago, has become part of The Odditorium’s furniture. “There are plenty of rooms to provide variety and the band was savvy enough to outfit each of them with unique interior design and lighting,” said Sherrer. “There’s even a patio on the roof for the occasional journey for fresh air! Though the Odditorium houses all the necessities for audiovisual creations, it manages to be far from a conventional studio space.

“There’s a sizeable control room that we use a lot to get ideas out quickly. And we often drag pieces of Pete’s pedal board into the control room and run that signal to amplifiers in the live rooms via tie lines. One of the nearby rooms has shag carpet on one side and a green screen for video on the other. It’s one of the quietest rooms in the building so I end up using it a lot. The shag side is great for dry sounds, and to achieve more ambience we can reposition closer to the green screen, which is naturally reflective. For really ambient sounds there’s another very large warehouse-sized room that’s wired to the bay. I like recording heavily compressed piano in there. I haven’t been able to get a similar piano sound in any other studio I’ve ever worked in; it’s truly unique. There’s also a large stage in that room where the band rehearses, so we’ll drag lines up there to capture Pete and Courtney’s live rigs. And there are a couple other rooms wired that we’ll use for the vintage organs or a

dditional isolation.

“The console there is a newer SSL AWS900. It’s a fine desk but doesn’t have as much colour as some of the older consoles that I love. I lean more toward the rack of original Neve 1073 and 1081 modules for preamps, EQ, and running program material through for that Neve bus flavour. Since we aren’t recording to an analogue medium we have some great outboard gear including Inward Connection tube preamps, Kush UBK Fatso, and Neve 2254s to add some of that flavour. There are also some great instruments and effects worth mentioning like the Roland Dimension D, Eventide H3000, original LinnDrum and Sequential Circuits drum modules, Korg MS20, Roland Juno, and much more. Pete [Holmstrom]’s guitar and pedal collection is outstanding, too. When I first started working over there I was also working with a small company called Hamptone where we built boutique microphones and preamps, so I was able to mod a few things in the studio that allow us to do things like run line levels through the Leslie speaker.”

THE LIVE RECORD

It’s been about 10 years and a couple of records since The Odditorium’s inception, so they decided to set a single ground rule that would discourage the day-becomes-night experimentation trap of owning a studio. After listening back to live recordings and really digging the sound, for This Machine, their eighth ‘studio’ album, they would attempt to only record what the four of them could reproduce live.

“It was just a natural evolution, we didn’t think about it too hard,” said De Boer. “We usually have a couple of basic ideas on which direction we want to lean and this time the idea was for us to record only what our four limbs could pull off when we were playing live. In the past we would overdub lots of guitars and layers of swirling stuff, so it’s a bit more stripped back.

“Of course, we didn’t completely stick to it because I played bass guitar in a couple of songs and there were a handful of overdubs. Just stuff that you definitely want to get on there for texture and execution.

“The tracking process went a lot faster because we all spent time playing the songs together live. Then we worked on them at home before showing up with definite parts that were the trippiest, coolest or most beneficial to the track. Actual studio time was cut down to probably a tenth of what we’d usually spend.”

Sherrer: “It evolved into a loose rule where each band member aimed for one instrumental performance per song, which encouraged a ‘make it count’ attitude. Of course, none of us really believe in rules when it comes to artistic endeavours, but we hoped to make this record a bit simpler with regard to track counts.”

We bought this old machine shop in North-West Portland — it’s a quarter of the whole city block

MINIMISING FOR MAXIMUM EFFECT

The minimalist notion also influenced Sherrer’s technical approach to the number of feeds and mic placement. “For instance, when you hear a trap kit in a room it is, for the most part, a monophonic instrument,” explains Sherrer. “Tom fills aren’t panning across the room, etc. That can be a fun effect, but a few well-placed mics can achieve a great recording without the accumulation of phase incoherencies that often blur the picture. We kept the process pretty simple using only about five to eight feeds on the drums and the minimum required on other instruments. We also did our best to make solid choices regarding instrument, pedal chain, and amp selection for each element.

“I usually use a variation of the Glyn Johns-style drum approach with ribbon microphones on top fed into Neve 1073s, 2254 or 1176 limiters and the UBK Fatso to give a bit of a tape sound. Guitars sound great through the Inward Connection preamps and a little API EQ. I usually have Sennheiser MD421s or Royer 121 microphones on the cabinet. Bass is the Korg MS20 synth straight into the tube preamps. Zia has those things on lockdown when it comes to dialling them in, so they don’t need much else. I’ll usually call up the Soundtoys Decapitator in the box which always does pleasant things on the MS20s. The string bass made a few appearances on This Machine. We used Peter’s vintage Gibson EB-3 outfitted with flat-wound strings, which is an amazing instrument. This guy usually goes direct into an API 512 preamp and levelled with the 1176 or 2254.

“As for ambience and depth I have to give a lot of that credit to Tchad Blake who mixed the album. He has a remarkable talent for blending and enhancing songs in a very musical way. I’ve been a long-time fan.”

Brent: “Everything sounds better when you run it through real great gear, with a guy like Tchad Blake that understands it all really well. He opened it up and let the mix breathe. It has a nice deep psychedelic sound. I have a digital stereo recorder that I sometimes set up across the room when we’re rehearsing, and at the front desk for some of the live gigs. This album sounds way more like one of those recordings than any of our other records.”

RESPONSES