In Deep With a Classic: Remixing Deep Purple

Martin Pullan balances where only the brave dare, and remixes the three concerts Deep Purple’s classic live album Made in Japan were culled from.

It’s the car crash syndrome. You know you shouldn’t look, but you just can’t help yourself. And in the music world, bad press is too hard to ignore: papers, blogs, forums — bad reviews are everywhere — just one look away from ruining your mood. It takes an iron will to look away, because we all want everyone else to validate what we do.

Rarely though do you see mixes evaluated. There are the widely scorned, like the mastering of Metallica’s Death Magnetic which became the poster child for everything wrong with the Loudness Wars. It was an easy target; the crushed dynamic range and excessive clipping made it simple to pinpoint the culprit. But for the most part, it’s too difficult to judge each contributor’s input. Was that blazing, clipped guitar a bad balance decision or a producer’s intent?

There is, however, one area where there’s a baseline for comparison. And consequently, an army of forum trolls poised with their opinions. I’m talking about remixing a classic album, and specifically, one of the all-time greats — Deep Purple’s live album Made In Japan.

It’s the definitive record of Deep Purple’s live prowess, with the original album’s track list cherry picked from three concerts across Osaka and Tokyo in 1972. Deep Purple fans really dig this album. And they know it inside out.

Martin Pullan of Edensound Mastering not only remastered Martin Birch’s original 1972 mix, but has remixed and mastered the entire three concerts — six hours of material — and now he can’t help but check in occassionally to see how the fans are taking it.

REMIXING A REMIX

By all accounts, the usability of the recordings was a surprise to everyone at the time. The band had set aside $3000 for the recording, but didn’t have high hopes for the outcome. Martin Birch, the engineer, was similarly skeptical when he saw the equipment the budget afforded — a skinny eight-track and no balance controls. But the whole thing went down live to eight-track tape, and became one of their biggest hits. The band have suggested part of the reason the performances are so good is because their expectations of the recording were so low they were only focused on the show.

The only time all three concerts have been mixed before, was in 1993 — at Abbey Road by Darren Godwin, assisted by Simon Robinson, the researcher on the project. It was a package called Live In Japan. “The general opinion is that, compared to the original, those mixes aren’t very good,” said Pullan. “My aim was to improve on that.”

So far, the reactions have been encouragingly positive. On one entrenched Deep Purple fan site, the first review reads: ’Are Martin Pullan’s mixes better than the 1972 ones? I dare to say, ’no’, but they come very close.’ Which is about as glowing as you can expect.

DEEP CONNECTIONS

Though he wouldn’t say it, Pullan is somewhat of a Deep Purple aficionado. He’s one of a handful of mixers over the years who’s been deeply embedded in the Deep Purple camp. His credits also include mastering for their Total Abandon Australia live DVD, he’s mixed and mastered a number of other Deep Purple concerts including from California, Paris, Stockholm, and projects for former members of the band including Blackmore’s Knight’s A Knight in York (5.1 and stereo) and Jon Lord’s Concerto for Group & Orchestra (5.1 and stereo).

But even though Pullan has invested so much time in the Deep Purple catalogue, he doesn’t bother himself with researching the minutiae of how the songs were recorded, what gear was used, or what the halls were like. Everything he needs to know can be heard on the eight tracks in front of him. Pullan: “Drums are a stereo pair; bass on one track — nice and distorted; guitar on one track — nice and out of tune — Ritchie would forever be tuning up his guitar mid song, those cuts never featured on Made In Japan; organ on one track; vocal on another; and then the luxury of two tracks for the audience.

“The original mix of Made In Japan sounds bloody awesome. The energy’s there, and it’s actually quite hard to get as good as it, let alone better.

“I try to bring a new approach. I’m not trying to be true to how they were mixed in the first place, we’ve got new technology now. We can jazz them up a bit and make them sound more exciting.”

These days, the number of tracks in a live recording would typically be upwards of 40. Regardless of the technology at his disposal, Pullan’s mix was still limited by Martin Birch’s initial decisions. “They only had eight tracks, and they had to make decisions and lock them in,” said Pullan. “The drum mix is really good, but because it’s on two tracks, it means I can’t separate things too much.”

One alteration Pullan did make, based on his knowledge of the band, was to flip the original stereo panning choices. The original has guitarist Ritchie Blackmore on the left hand side, and Jon Lord, the keyboard player, on the right — a configuration they never appeared in on stage. One of the many releases in this new batch is Kevin Shirley’s original 1972 album remix plus Pullan’s new encores, which is a bit weird, because it flips between the two panning choices. “I took it upon myself to change it around, not really thinking about this permutation. My decision may have been a foolish one,” concedes Pullan. “Some people have mentioned it, and they think it’s a mistake.”

RECALLING 1972

As well as the number of tracks, a big difference between today and 1972 is the choice of whether to mix in-the-box or on a console. Pullan makes no bones about it, he’d rather be in a DAW. “I think you can get it better,” he said. “I come from big old analogue consoles, started on a big old Neve and worked on all of them. But I much prefer mixing in-the-box because of the amount of control. Besides, if you mix in-the-box and tell someone it was done on an analogue console, they’d believe you. There’s no way you can do all those fader rides with an analogue console, particularly in the days before automation. Plus, you don’t have to finish the mix at three in the morning when everyone is tired. You can come back to it exactly as you left it and refine it. There is a danger of over-refining, people will just pick at things until they bleed — so you’ve got to be careful.”

Pullan was supplied with 24-bit/96k transfers from when Made In Japan was remastered. He still uses ProTools 9, because he keeps his TC Powercore card around when he has to master 96k files. Typically he would master through an analogue chain, but his hardware TC Electronic Finalizer only runs at 24-bit/48k. The Powercore card gives him access to TC’s MD3 stereo mastering tools from the System 6000 for those high definition Blu-Ray releases. Pullan walked through each of the eight tracks and offered insight into how he applied 21st century tools to a ’70s rock recording.

The original mix [of Made In Japan] sounds bloody awesome… it’s actually quite hard to get as good as it, let alone better

MASTERING YOUR OWN MIX

With roughly 21 years between each of the releases — 1972, 1993 and 2014 — there has also been a number of format changes. And while the CD was around in 1993, Pullan notes they didn’t start to get really loud till about 1996. So the only version he was competing with was Kevin Shirley’s recent remix of the original.

“Mastering older versus newer material isn’t really a different process, except for being extra conscious of not slamming it too hard,” said Pullan. “It’s a bit of a balance, because you can’t finalise something for digital release that’s really quiet.

“I tried not to squash it too much, but I was also conscious of what Kevin had done with his, in terms of level, and his was reasonably loud. My aim is to get something reasonably loud, without killing the dynamics. I’ve used a lot of boxes, but find I’m able to do it better with the TC Finalizer than anything else. Particularly because you can change the shape of the soft clipping, whereas with a lot of other boxes like the Waves L2, there’s no choice, it is what it is. Even with the TC plug-ins, I can’t get something as loud and punchy as I can with the Finalizer itself.

“I was at Abbey Road and they had a TC System 5000 there, but never used it. It was a remix of a Pseudo Echo track I’d mastered here, and they really wanted me to match it, but I couldn’t. They couldn’t get it as loud and punchy with the gear they had there when they weren’t using the 5000. They weren’t normally concerned with getting things loud, because it’s not their thing, but I really needed to match it. The engineer didn’t know how to use it, so we got the tech guy to set it up, and we both tweaked things till it sounded good. But it was still a challenge. For some reason the Finalizer is easy to use and makes sense to me. I think a lot of people don’t like it because of some skewed perception, but clients don’t tend to care about esoteric gear, it’s just how it sounds.”

Mastering your own mix is often considered a no-no, but when you’re an experienced mastering engineer, it’s easier to have the required objectivity. Pullan keeps mastering in mind while he’s mixing, because there are certain things he finds easier to apply to a stereo master.

Pullan: “Sometimes there’s an accumulation of resonance because of the keys of songs. It’s not something you’re necessarily conscious of when you’re mixing individual tracks, as when you’ve got them all in. So you might not go in to every track and reduce one particular frequency, you might do it on the whole lot at the end of the day.

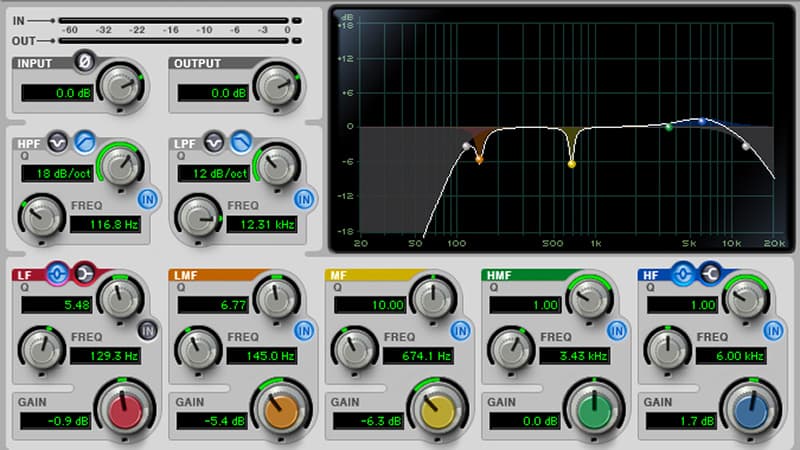

“I try to treat it like it’s someone else’s mix, and that I haven’t got it all right just because I’ve mixed it. I’ve taken some width out of the lows, interestingly, and added some overall width. You’ve got to be sensitive though, if you bring the sides up too far you’re going to lose your vocal, snare and kick drum. But it does tend to give the mix a bit more overall excitement. Then I’ve got two plug-in EQs, plus I used an analogue EQ, and two lots of analogue compression — a multi-band and single band compressor. Then I also used some EQ and three-band compression in the TC Finalizer as well.

“I was using CD Architect on my PC to assemble the final master. But now I tend to put together DDP files in my Mac, rather than physical CD masters. I still think it’s a good idea to have a different physical machine to record onto, just because of the processing and the disk usage. So I’m sticking with it.”

MIXED RESULT

Pullan’s mix is a lesson in creative restraint and an ear for detail. The remix isn’t an over-the-top parade of sizzle. It’s a ‘true to the source’ remix, that brings a worthy level of detail, brightness and excitement to the recordings absent from the 1993 versions. And that’s what fans want to hear.

A tip for all the audiophiles harping on about the warmth of vinyl: Pullan says the vinyl versions are actually a bit toppier than the CD. “I asked them when I heard it back,” said Pullan. “Because I wasn’t sure if it was my replay system or not. But they confirmed the mastering engineer at the pressing plant added some top end. I didn’t mind, but it’s funny that the vinyl sounds harsher than the CD.”

thanks a lot!