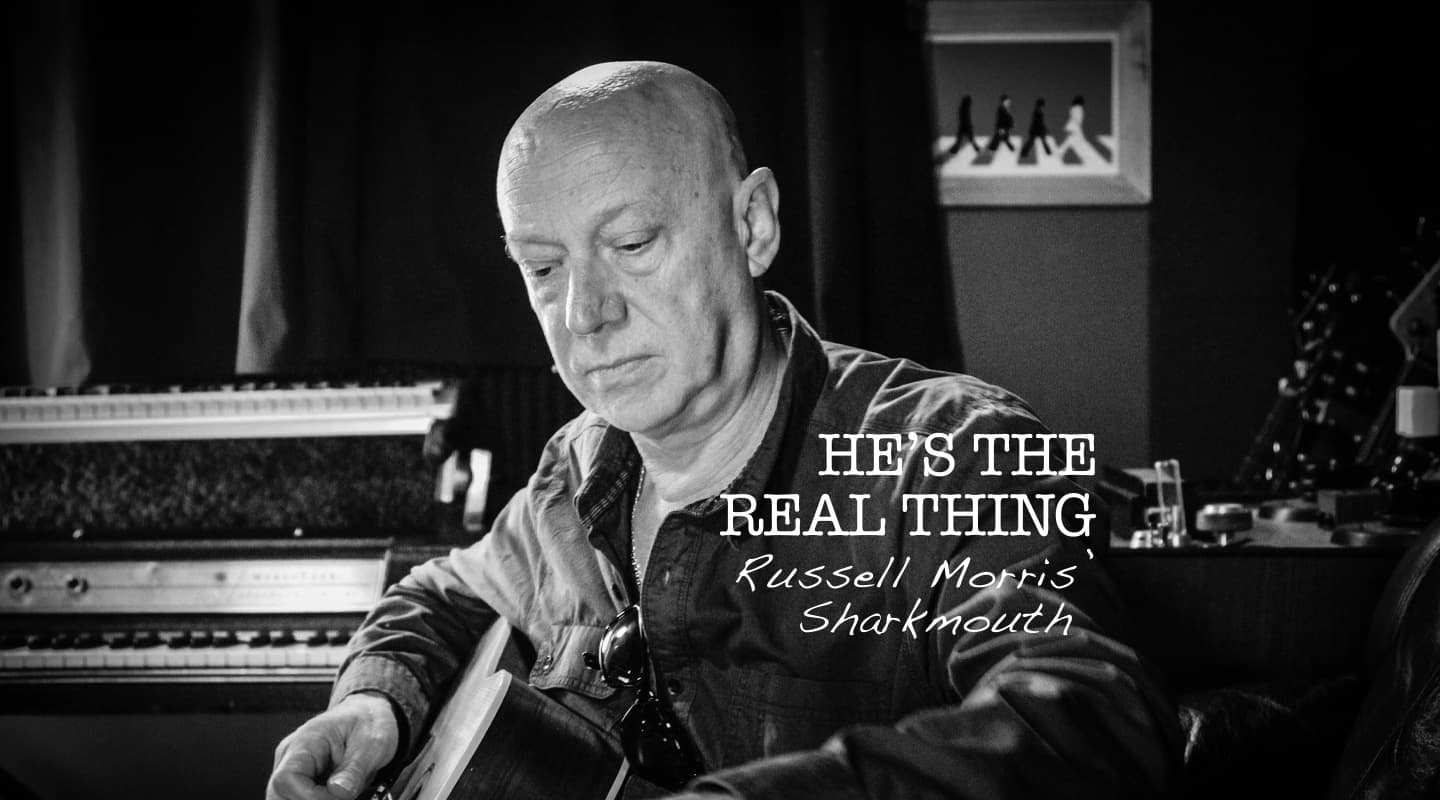

He’s The Real Thing: Russell Morris’ Sharkmouth

The most successful Australian record in the past year was a concept album by a 60-year old man, produced by a comparative novice with almost no budget or industry support. That album has just gone platinum, won an ARIA award, and provided a 45-year industry veteran with the biggest success of his career. Russell Morris’ Sharkmouth is a real Aussie battler yarn.

Story & Photos: Michael Carpenter

Russell Morris has outlasted generations of industry movers and shakers. His iconic hit from 1969, The Real Thing, is a significant part of the late ’60s Australian rock story, and was recently made a new exhibit at the National Film & Sound Archive’s Sounds of Australia. Morris enjoyed considerable commercial success through the early-mid ’70s. Since then, although hits have been scarce, he’s worked consistently and tirelessly as a live performer, releasing countless records that largely went unnoticed.

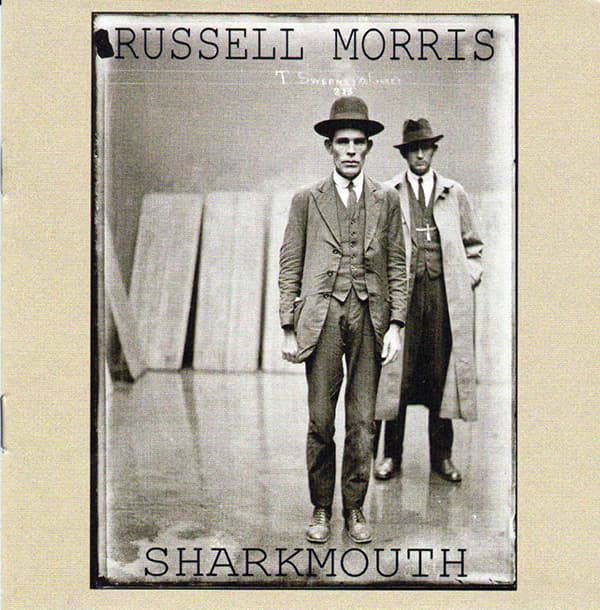

That all changed recently with a bit of help from a petty criminal. In an A Day In The Life moment, Morris, while reading the paper, came across a photo of con man Thomas ‘Shark Jaws’ Archer taken in January 1921. It captivated the songwriter. “I love history,” explained Morris. “That’s all I watch on television and read about. I saw the photo in the paper. It was almost like it spoke to me, saying, ‘I lived. No one knows about me. Tell them that I lived.’ And I thought to myself, ‘I’m Australian. This is my roots. These are my blues’.”

Almost instantly, the lyrics to the song Sharkmouth were written, and that became his direction. Morris would research the history of other Australian characters — from boxer Les Darcy, to gangster Joseph Lesley Taylor (‘Squizzy’) all the way to Phar Lap (‘Big Red’) — and phrases would start to appear from which he’d piece together poems.

Initially four songs were written and long-time touring band bassist, Mitch Cairns, who at that point was a relatively new producer/engineer with a modest studio setup, suggested they ‘put them down and see what happens.’ This low key starting point liberated them, allowing them to work without boundaries. Morris: “We had no sense of expectations, except our own.”

PRIMITIVE SOUNDS

A historical Australian narrative presented in a contemporary blues idiom was a road rarely travelled. But from the start, Morris had a clear idea of how he wanted the record to sound. “I wanted it really basic,” said Morris. “Primitive… I’m writing songs about the 1920s.”

Cairns concurred, “It’s really only drums, bass and main guitar (often one guitar and a solo all in one pass). There’s no percussion, hardly any keyboards, minimal backing vocals, and a couple of Russ’s two-part harmonies we wanted right down in the mix. Super minimal.”

The album almost has a classic ’70s sound without being overly retro. Morris explained, “On my previous record, I was chasing the pied piper — I was doing it for all the wrong reasons. So this time, I was really committed to just doing what I liked.”

Sharkmouth is an honest sounding record that doesn’t sound like anything in particular. “While I’m making a record,” Cairns explained. “I don’t really listen to reference CDs. I’m more interested in getting a bunch of guys I know and trust in a room with good songs and seeing what happens.”

The occasional imperfections work perfectly in the context of what the album is trying to say and be. Cairns: “There were times where a part would speed up, or lean forward in the groove. Or Russ would push a little sharp on a vocal. These were some of our favourite bits. In fact, when we’d go to fix them, it almost always sounded contrived. That was one of the other big rules for the album: If anything came across as contrived, I immediately deleted it.”

This became such a big part of the story being told that even later in the process, when there were options to send the record to Nashville or LA for mixing, Morris and Cairns declined. Cairns: “They’d have put it all on the grid and fixed it all up. But that would have defeated the purpose of what we were trying to say.

“I’m also a firm believer in commitment to sounds. The choice of player, instrument and microphone can really affect how the record takes shape, so it’s important to keep focus on the result and make decisions accordingly. I like to go through and delete stuff. I don’t need 300 takes of something. Mistakes can be fixed, but money can’t buy vibe!”

The effect of these production guidelines is that the album has a life and a feel to it, that, when combined with the stories, presents a distinctly Australian record. Cairns said of Australian Blues: “It has a certain edge to it. The groove pushes forward a little bit. We play blues like it’s pub rock… like it’s a pub fight. Americans can’t do that.”

INDULGENCE IN MINIMALISM

The initial sessions for Sharkmouth took place at Cairns’ old space at Rooftop Studios (owned and run by Steve Morgan) and Little Red Jet Studios in Melbourne — a modest setup with an Amek BC2 console “and a tiny dead booth.”

Cairns and Morris worked together on getting structures, feels and tempos outlined. Between them, they worked up guitar and vocal guides to a click in ProTools, ready for drummer Adrian Violi to play over. The guide tracks were hardly inspirational for Violi, which made the work he did even more admirable. With no demos to listen to ahead of time, Violi relied on instinct, Cairns’ direction, and a long discussion about the meaning of the songs and the mood being created by the narrative. He nailed the four tracks in the first or second take — an evening all up, with no comping. As Violi explained, “Knowing what the song was about was absolutely the most important thing. The structures were relatively simple, and what was being asked of me wasn’t that tough. But knowing what the song was saying meant I played the songs with meaning.”

This narrative-driven approach was reinforced by Morris throughout the process: “For every part of this record, from the drums all the way through to the mastering, I made sure that the people involved knew what the song was about. In every case, they approached their part differently — as if they were being guided by the characters in the story.”

We play blues like it’s pub rock… like it’s a pub fight. Americans can’t do that.

PRIMARY COLOURS

On a record as unadorned as this, every colour is critical. Arguably the most important colour on the record apart from Morris’ vocal were the guitars of Shannon Bourne. Once Morris heard his own rhythm guitar parts reinterpreted in Bourne’s hands, he instructed Cairns to delete the guides, to avoid them colouring Bourne’s own interpretations. Working from Morris’ ideas as the writer, and basing the songs around a single acoustic guitar wherever possible, the team took their time to get the sounds and feel right. Morris says of Bourne’s guitar playing process, “Sometimes he nailed it straight away. Some of the songs he bent out of whack from where I saw them… some in a good way, some in a bad way… he’s such a genius at times.”

Cairns: “If it’s going to be one acoustic guitar, it’s not only got to sound great, but it’s got to be the right guy, playing it with absolute conviction.”

The acoustic guitars (made by Churchill Guitars in Ballarat) were usually recorded with a combination of a Neumann U87 and AKG C451, through the Amek, with minimal tracking compression through a UREI LA4A. It took a long time to get any electric guitars on the record, as Morris had been trying to avoid them. When they finally did appear, they were always unusual rustic old guitar/amp combinations, with a deliberate absence of Fenders and Gibsons. They were recorded with a combination of the U87 or FET47 and Beyer M88, through the LA4A.

The cosy room at Rooftop painted Cairns into a corner with the drum sound, a suffocating lack of ambience he relished. Cairns: “I wanted to make it as dead as I could, and Adrian threw a lot more gaff on the heads and made them really dead. We tuned the snare down as low as we could too. Because the room was so small, we ended up with this fat, fleshy, lifeless, dry tone, that drives the songs perfectly. I like dry recordings, dead drums and not a lot of toms.”

Cairns took care of the bass tracks himself. His chosen tools were generally a ’62 Fender Precision with flatwounds, mostly played with his thumb, through an Avalon U5 DI, into his trusty LA3A compressor, just grabbing 4-6dB of gain reduction. Cairns: “I wanted the bass parts to feel substantial and add weight to the drum tracks, but never draw attention to themselves.”

Finally, there was Morris’ vocals, recorded through a Neumann FET47, through the Amek BC console with a little top end EQ, into the LA3A, grabbing 6-8dB on the loudest phrases. “Russell is such an amazing singer,” said Cairns. “But more than that, he just knew what he wanted. I thought most of what he sung was incredible, but he would subtly change approaches from take to take. And we were always aware of that moment when things sounded even the least bit contrived. It was really important to Russell that the vocal reflected the story, and that it never came across as Russell ‘putting on’ a voice and approach.”

REVIVING THE ACT

After the first batch of four songs were completed (Black Dog, Les Darcy, Sharkmouth and Big Red) there was an extremely long pause. At this point, it was just recording a bunch of songs — it wasn’t considered an album project yet. More than 18 months later, Morris’ upcoming live show bookings looked a little slow, so he and Cairns decided they’d better finish the record. Fortunately, the process of these initial sessions had ignited Morris’ imagination, and the remaining eight songs were mostly formed, with some notable co-writes, including Jim Keays, Gary Paige and Cairns himself.

They approached these next sessions in a similar format, keeping the ensemble small and focused, including Cairns, Violi (who smashed his way through the remaining eight drum tracks in one evening) and Bourne. They acted quickly and instinctively, with simple recording processes and character in performances being preferred over artifice.

Some of the guest artists featured on the record include Renee Geyer, Mark ‘Diesel’ Lizotte, Troy Cassar-Daley, Chris Wilson and James Black. Cairns explained the process: “We were very careful about asking too many guests. They had to have some sort of connection with Russell. We were aware they probably get asked to play on people’s records all the time, so we had to have a different angle. For example, rather than approaching Diesel to just play another cracking guitar solo, we asked him to play banjo and cello on Squizzy. It ended up really guiding the tone of the track.”

The conscious lack of layering means that when guests appear they become real events in the story of the album. For instance, Renee Geyer’s vocal on The Drifter pops up halfway through the album and provides a change of tone that draws you further into the narrative. The guests’ parts were sometimes recorded by Cairns at his studio, and the rest of the time recorded by the guests in their own studios and sent in via the internet.

As is the case with most recording projects, there’s always a track that has a difficult birth. On this record, it was The Bridge. After Morris struggled to complete the lyrics (co-written with Alan Howe), they also found it difficult to get chord progressions and melodies they were happy with. Frustrated by the way the track had evolved in the writing process, the instruction to drummer Violi was to “really lay into it and give it something”, while guitarist Bourne pulled out the baritone guitar, tuned down to low C, and came up with one of the most distinctive guitar tones on the whole album. On the back of this sonic rejuvenation, Morris, frustrated with how average the vocal was, came in right near the end of the album sessions and sang the vocal an octave higher, in an attempt to give the song some life. “I screamed it,” he said. “If you listen. It’s sung at the end of my range.” Where many may have ditched the track after the writing process, Morris had no choice: “We only had 12 songs — there was nothing in the tank. So we had to finish it!”

THE FINISH LINE

By the time recording was finished, both Cairns and Morris were creatively fried. Cairns didn’t feel he was in a position to mix the project, so he called on David Carr of Rangemaster to reprise the role he took after the initial four songs were recorded. Given an email brief with the full story on the character driven material, and the tonal concepts of keeping it ‘primitive’ and ‘classic’ were reinforced, Carr was left to his own devices, mixing a few songs at a time and then inviting Morris and Cairns to come in and critique the work and tweak the results. Cairns: “Some of them were right on the mark and some needed to be brought around to where we wanted them to be. There was only one (Mister Eternity) where he really missed it, and even then, once I’d explained what I wanted, he got it straight away.”

Once the mixes were signed off, the final step was mastering. Aware of the fact the budget was almost non-existent for both mixing and mastering, Morris looked for a cheaper option just to get it done. But Cairns pushed to have the record completed by John Ruberto at Crystal Mastering. Cairns: “I told John, ‘It’ll never get played on the radio, so don’t fucking slam it.’ And he did a fantastic job. Which just goes to show, you don’t have to master for radio.”

PERSEVERANCE PAYS

Between and after the two sessions, Morris, who felt the first four completed songs were among the strongest of his career, had started shopping them around through his many industry contacts. The reaction was underwhelming. Morris: “We got rejected multiple times by people who I thought would understand what we were doing.” At the last minute, after the initial, self-funded pressing of 500 was completed to sell at gigs, Fanfare Records, who’d rejected the album, gave it another listen and decided to throw a little bit of money at it. The rest, as they say, is history.

The album was released in 2012, and slowly, on the back of Morris and his band’s relentless touring, started to gather attention. “Radio DJs had been dismissing me for so long,” said Morris. “When they finally heard it and realised it was good, they got behind it.” Airplay on national stations, positive reviews and word of mouth fuelled interest in the record. After a few months, the album entered the ARIA charts at No. 80. (Morris: “We were over the moon at that. We never expected it to go any higher.”) The album continued to climb, eventually reaching No. 6. It has been in the charts now for almost a year, and has held the No. 1 position on the iTunes Blues charts for over 12 months. It also went on to win the 2013 ARIA for Best Blues & Roots Album.

It seems like the perfect marriage of a talented, experienced artist who has continued to create after any real hope for commercial success had gone, and a young producer who believed not only in the artist, but also in the musicians he assembled for the project. As Cairns explained, “The hardest part was keeping an absolute focus. Russell had a focused vision right from the start — primitive and simple. Having that focus over two years, and having to drive it into everyone… that’s what made the album.”

RESPONSES