Good Buzz: Radiohead Live

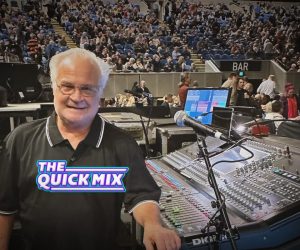

Radiohead’s FOH engineer Jim Warren turns in a dynamic performance.

Photos: Marty Philbey

When you lay your head on the pillow after a great gig, you usually have two types of buzz. The first is good: an electric satisfaction of having shared an enlightened musical moment; having ‘been there’; touchy-feely moments to stuff in the memory bank. The second is bad: a gentle hum that slows your descent into sleep as the early stages of tinnitus set in. You usually have to take the good with the bad, or stick your earplugs in and shut out half the moment.

Radiohead live was all good, no bad. Bafflingly so. Here was a band, in an arena, with enough PA to scare the neighbours, and no bad buzz. And before you go saying, ‘Radiohead are soft anyway.’ Listen to Myxomatosis on Hail To The Thief, and imagine two drummers, two analogue bass synths, two guitars and mega vocals, performed like a maniacally heavy club jam through an arena PA. Not light stuff.

In the week leading up to the Melbourne show we’d heard an entirely different buzz, about how good the show sounded. But we’d already committed to covering Coldplay, having covered Radiohead the last time they were out. So we left it at that.

But the superlative reports were well-founded, and it was impossible not to catch up with Radiohead’s engineer, Jim Warren, and ask the long-time mixer how he pulls it off these days.

UPS & DOWNS OF LIVE MIXING

Mark Davie: One of the striking things about the show was after a couple of hours with no ear-plugs you could walk away without any ringing in your ears. Is it purely about level or something more

than that?

Jim Warren: One of the biggest things with Radiohead is they’re very dynamic, which is a huge help for not mixing loud. There’s plenty of parts where it comes right down so you get the impact and excitement of the next surge in volume, even though it’s only as loud as it was earlier on. You don’t have an ever-increasing volume.

Ever since I started mixing I’ve always tended to mix quieter than a lot of other people. When I was a young lad I would mix the opening acts. Quite often I’d worked with the band in the studio and knew their music pretty intimately so I’d mix it accordingly. Then the headline band would come on stage and it would be like a volcano explosion and everybody would go nuts. And I’d be thinking, ‘Maybe this is what I have to do? This is what people expect from a live gig.’ Where everything shakes your chest and blisters your ears.

I’ve been mixing this lot from back when we were in little clubs 20 years ago now, and they lend themselves to being mixed at a reasonable level. Plus, he can actually sing, so it pays to be able to hear the vocals. Also, it’s quite complex music, and the louder you go, the harder it is to hear everything that’s going on. The people that come to see them seem to appreciate the fact they can listen to it and hear everything, yet not go away with their ears ringing. So it’s self-perpetuating.

I like to see people with earplugs in at the start of the show, getting two or three songs into it, taking their earplugs out and this look coming across their face of, ‘Oh, that’s okay!’ It does strike me as odd that after 50 years of live rock music it’s almost accepted that if you go to watch a live band you need to wear earplugs.

MD: So did you end up differentiating your live mixes from the studio work?

JW: When you do a studio recording it has to work on everything from the tiniest speaker to a club system to going on the radio, and you therefore tend to make a lot of compromises.

Live music is just about the only place where dynamics exist because you can control them while in the same listening environment as the listener. Quite often people go and listen to the records and come back and say, ‘It sounds so small on the record. I can’t believe how powerful it sounds when it’s live.’

As much as I’d like to say, ‘Yeah, well that’s my powerful mix.’ It’s because it’s happening right in front of you and you’re wrapped up as a part of it. If you were to take that mix away and listen to it on your laptop, it will come across completely differently and you might start making those compromises again to make it work on the laptop.

What I enjoy most about live mixing is certainly the spontaneity of it and also that you’re there with the audience listening to it at the same time, so you can be happy with what you’re hearing at that time rather than having to try and project that into 20 different listening environments over five different media.

DOUBLE DRUM TAKE

Probably the biggest change for Warren this tour has been the addition of a second bald drummer, Clive Deamer, to the lineup. He and Phil Selway lay down some incredibly complex rhythms, and at times both guitarists Ed O’Brien and Jonny Greenwood, join in the fun on their own concert toms. Funnily enough, Warren had just come off a tour with Arcade Fire, who aren’t shy of a little double drummer action. So he was well prepared to take on the task.

JW: My take on two drummers is always to try and find differences between the two drum kits and highlight them to get some sort of definition between the kits. Because Radiohead plays a range of songs from full-on loud, rock styles to stuff that’s basically jazz, Phil’s drum kit has never been a pure rock kit. I’ve always got him to leave plenty of life in it. So when we started rehearsals at the beginning of the year, I assumed that Clive’s would be the rock kit, and Phil’s would stay as it was and be the jazz kit. As soon as I heard Clive’s kit I realised that wasn’t the case — his is completely jazz and tends to be more funky and crazy sounding — so I went along that road.

I do a little panning, though not too much because it starts to get a bit weird in arenas.

I essentially mic up both kits the same way. It wasn’t necessarily an artistic decision, more a practical one. During the last 10 years they’ve always promised to simplify things. We started off as a basic three guitars, drums, bass setup and then they started adding in the keyboards, the samplers, the Rhodes, the piano, and it quickly became pretty big and unwieldy.

This time we started with a more simplified setup, but then they added in everything that they’d ever had before, and more. I said to them in rehearsals, ‘The absolute limit for channels we can get into the stage boxes is 96, and we’re already at 90. So be aware that if there’s much extra we’re going to have to leave something out.’

Some people use 20 channels on a drum kit, but I don’t have 20 to use on each, so the miking is pretty basic. Each kit is covered by eight or nine faders, a couple of which will be stereo for the electronic parts. For instance, we only have one mic on the snare drum. I have done stuff within the last few years where I used the top and bottom snare in the traditional fashion, but it always strikes me as being a bit of a bodge — trying to make a snare drum sound out of two that don’t sound like snare drums at all. Whereas if you play around you can usually find a place to get a good snare sound with one microphone.

I have this technique I started using with Radiohead on one of their records. The drum sounds were really funky and sounded like

they were recorded in someone’s bedroom. Phil isn’t a very hard hitter and that tends to mean the cymbals are relatively loud compared to the drums. You don’t get much more volume out of cymbals by hitting them harder, they’re always loud.

So rather than using an overhead I’d stick a mic right in the middle of the kit and I was amazed at what a fantastic sound you can get out of one microphone, especially with a bit of compression on it. Every now and then I’ll pull that fader out and be astonished by how little of my drum sound is left if I just take one microphone out.

It’s the drum sound, and you can add in what you need to make toms a bit more meaty and things like that — that technique alone has made it.

I use different mics in that position, depending on the style of the drummer and the sound of the kit. The ones I’m using at the moment are little Audio-Technica ATM350 gooseneck cardioid mics that just clip onto the top of the kick drum. The 6-inch long gooseneck takes it out in front of the kick drum to where it sits right in the middle of the kit, with almost equal space between the kick, snare and two toms. And then I squash it with a compressor to take care of the level differences.

You get such good presence out of it. You can use it on days that are a little darker and things aren’t cutting through so well, you know that just a little push on the fader will bring it alive, rather than having to go to the EQs on every single piece. Even within a song, just a little push on that will really bring the drums forward in a section.”

MD: Do you use any specific style of compression on it?

JW: All my compressors are plug-ins and I’ve experimented with various ones, but I’m actually using the Waves V-Comp, their ‘vintage’ compressor. It’s got a little bit of everything, and some interesting adjustments on it.

You have to make all those decisions very early on. People seem to imagine that you have all the time in the world to muck around and experiment with different mics. But the reality is our monitor guy would have a heart attack if I was turning up wanting to try a different mic on things. He’s got to make it work instantly in who knows how many mixes. And for monitors, it’s all about stability and consistency. So things only get changed if there’s a major problem, otherwise you just go with the stuff that you know.

And because that one mic has such a huge impact on the sound of the whole drum kit, once you’ve got it in there and working, to make any major changes to say, the compressor, you’ve got to change or revisit that in 30 to 40 different snapshots. On my desk at the moment I think I’ve got 80 snapshots, sometimes more than one per song.”

ALWAYS SPACE FOR MORE ECHO

One addition Warren has made to his setup since the start of the year isn’t a superlative vocal channel strip, or an outboard drum bus compressor, but a humble Roland RE-20 Space Echo guitar pedal that sits right on top of his Venue console. “For all the amazing creative power that you get from having plug-ins on the desk, they still lack that tactile response,” said Warren. “With the pedal, I can just bang a tap delay into something, and crank the feedback. Finding your way to the correct page in a plug-in can sometimes be more complicated than actually performing those functions themselves. It does the bulk of the spun-in vocal delays. It makes you realise that you can make a particular pot on a desk as multifunctional as you like, but there’s no substitute for having a machine that sits there and does one thing well.

The louder you go, the harder it is to hear everything that’s going on

ACCIDENTAL SAVIOUR

MD: What are some of the biggest changes you’ve made with Radiohead?

JW: Well the biggest thing is the digital desk. Back in the good old days when there wasn’t

such a thing as a live digital desk, I had a small digital console that I used for effects returns. I was using a Soundcraft desk that had snapshot recall of a kind. It would at least allow you to mute channels that weren’t in use. But even 10-12 years ago the band’s channel count was verging on the unmanageable.

And when the band introduced the samplers, it added another 12 channels that I didn’t have room for on the analogue desk, so I put all those on the digital desk too. It meant I was already into mixing in snapshots so it was a fairly easy transition.

Now I think of how different they are from song to song, and the amount of work I can do by just pressing a button and moving to the next snapshot. I would have to mix very differently on an analogue desk.

I’ve been using the Venue for getting onto seven years and I’m very comfortable with it and can work very fast, but if you were to give me a band that I’d never met before to mix that night in a club, I would still prefer to be given an analogue desk. The digital desks really only come into their own when you have pre-production and rehearsals, and time to program everything up.

What scares people about them is I could push a button and it will pull all my faders down to nothing. Even on this tour I think I managed to do it once. I have a snapshot called ‘The Workshop’, which is how the desk sits all day long when we’re not using it, so it doesn’t matter if something gets accidentally pushed or nudged. I’ve managed to store that over a song. I recalled the song halfway through the show and suddenly watched all my faders drop to the bottom…

You’re trusting the machine to take a lot out of your hands, so you have to be confident in your use of it to not give yourself heart attacks.

LAYERED CHAOS

MD: Does the looping and layering ever get so out of control that you’re pulling your hair out?

JW: Yes. That’s part of the beauty of what they do. There’s a lot of stuff they do that could be done a lot more repetitively and a lot more dependably. Jonny basically has an FM radio onstage that he fires into all of his pedals.

In the lead-up to the show, his tech will get six presets — some classical music, some spoken word — come the gig, sometimes radio reception is so bad that all you get is interference. In the past we’ve floated the idea of having some sample backups, and they always say no.

Recently, someone was asking one of the guys, ‘Who does the playback?’ And he replied, ‘There isn’t any. It’s all generated live.’ And it’s the way they want it to be. Sometimes it creates problems and leads to a bit of a disaster, but they just shrug their shoulders and go, ‘Oh well.’

Sometimes it’s absolutely magical. They get away with it because they’ve managed to establish themselves as a pretty successful live act and a bit alternative about the way they do things. Their fans realise that you have to take the rough with the smooth. The magic only happens if the random element is there.

I’ve worked with bands where everything was sampled along with backing tracks. It’s reliable and predictable from day to day, but with that predictability you lose a bit of the creative spark.

RESPONSES