Flight Mode

Flight Facilities’ hybrid touring rig combines Ableton Live sounds with tracks cued from a Pioneer CDJ2000 flight deck. Buckle up and stow those tray tables.

The appeal of live music is, at least in part, about witnessing something unique. It is, by definition, a one-off, never-to-be-repeated performance.

Depending on the type of music, an audience feeds off the energy created by a group of musicians doing something rehearsed but not entirely planned. It can be dangerous and exhilarating, like watching a high-wire act.

Electronic music creates a problem for the performers. Some of it simply can’t be physically performed. Other parts can be performed but the nuances from the studio production are almost impossible to recreate, which could easily disappoint audiences.

I recall attending a PA (personal appearance) in Melbourne of the legendary Detroit techno pioneers, Underground Resistance. Admittedly this was the early ’90s, but the ‘performance’ entailed Underground Resistance’s designated DJ spinning their tracks while they stood in the corner nodding. Awkward.

Orbital turned electronic music into a performance event, headlining Glastonbury’s main stage for a number of years in the ’90s. The Hartnoll brothers proved that live electronic music needn’t be akin to karaoke.

There have been plenty of bands since that have ‘skinned’ the electronic music ‘cat’ in a number of different ways.

Flight Facilities has a couple of live approaches. The recent Aussie tour used their more ‘portable’ rig.

Unusually, at its heart is a full-blown Pioneer DJ rig.

Flight Facilities — Hugo Gruzman and Jimmy Lyell — love to DJ. So when they built their live rig, it felt right to integrate that passion.

Unlike most live electronic acts, where the audio is piped out of a MacBook Pro loaded with (inevitably) Ableton Live, Flight Facilities’ audio sits on the Pioneer decks as Wav files.

Don’t panic, they do run Ableton Live! But only as a sound source, not for tracks.

Hugo has an MPC-style pad controller which he uses to cue Ableton Live setups — loading a new song’s worth of soft synths and samples (Chain Selectors in Ableton speak).

There’s no sync between the tracks residing on the Pioneer decks and the Ableton instrument scenes. They’re entirely independent.

I’ll allow FOH engineer Fraser Walker to take over and talk us through his setup.

DIGITAL THINKING

Fraser Walker: Anto (Anthony Pink, monitors) and I share a Digico SD rack connected via fibre. I prefer this approach to a copper split. This way you get your gains right and you’re done.

We take all the tracks from the Pioneer CDJs digitally (S/PDIF) and into the rack via a Neutrik impedance converter so it can run as AES. Those tracks are a good 80 percent of the audio content and it’s all digital. Which is great.

All up, I have 12 input channels running through two groups plus effects returns. It’s all manageable enough to be run from a Digico SD11, but due to availability we’re running an SD5. I’m not complaining, it’s nice to spread out and get comfortable. I’m running a desk snapshot for every song. And doing a fair bit of processing, especially on the guest vocals. [Read about Fraser’s plug-in-heavy vocal chain later.]

HEAVY PROCESSING

Fraser Walker: I’m not getting stems or individual backing tracks from stage — it’s a highly produced and radio-ready stereo mix which the guys perform over and the guest artists play and sing over. It means I need to carve out a space for everything that comes after the DJ tracks, to fit them in and to sound correct. For example, the vocals: you can’t squash everything together at the end because the tracks are already heavily processed.

The challenge is for the instruments and vocals to match the radio-ready sound of those backing tracks. If you don’t, it sounds amateurish and badly mixed. That guitar, sax or live vocal really has to sit in the pocket.

When I explain it, it all sounds a bit overly-tweaky. I mean, if I was mixing 40 channels of live band, I wouldn’t even come close to doing all this sidechain and mid-side compression, because you wouldn’t need to. You’d control the individual elements of the mix. If you’ve got a guitar in a band then you can do what you need to do to ensure it fits into a small pocket in the mix. But a guitar already mixed in a two-track production is largely beyond your control.

SURVIVING COMPUTERS ON STAGE

If Fraser is the guy to glue the performance together it’s Andy Alexander’s job to glue the elements of the stage together. He’s the go-to guy for Flume as well. Andy’s an expert in optimising a stage setup with a computer at its heart and then doing all he can to ensure there are no catastrophic failures.

Andy Alexander: A lot of it is in keeping the show file super lean. By which I mean, keeping the file size down by refining your use of samples — lose anything that’s unnecessary.

I like to keep the CPU usage ticking along at around 10% to give ourselves plenty of CPU headroom for performing.

Depending on who’s playing and how percussive the playing is, you obviously need to have low latency. As you lower the latency settings you’re geometrically increasing the processing required. It’s a compromise. I’ll work on a happy medium with the player, such that they’re playing with the highest latency they can put up with — it’s not bothering them but we’re keeping the processing power lower.

Hugo is clever with Ableton. Other than adjusting the buffer and cleaning out old files and samples, his show file was already pretty optimal.

During the show I’m screen sharing from side of stage. If I see something going awry I’ll use a break in the set to physically swap computers. If there’s something weird happening I can control it and I’ll hopefully avert disaster via a screen share.

CABLE DISCIPLINE

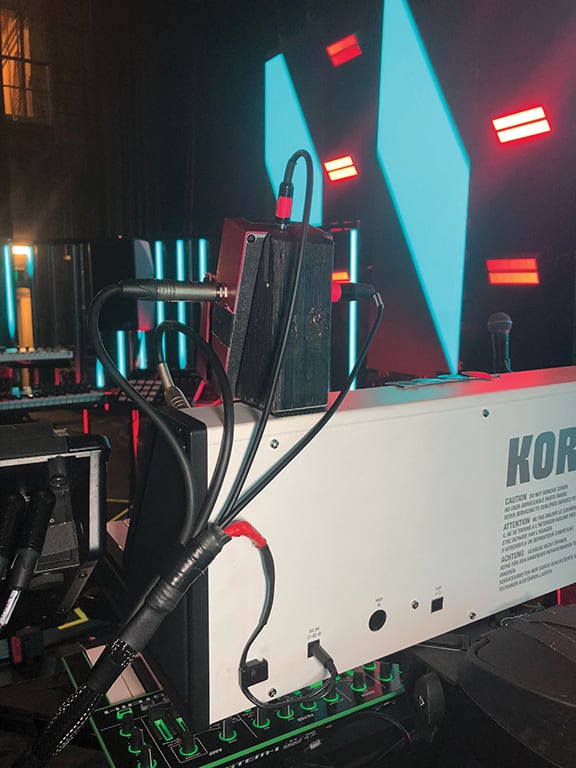

Andy: The second most important thing on stage for stability, is cable discipline — having redundant power and signal lines built into your looms so you can troubleshoot and fault find quickly.

Experience helps. Experience allows you to quickly fault find based on your own range of experiences. For example, after a while you’ll become familiar with the sounds a computer makes when it’s going to fail.

Low voltage plug packs are everywhere but not designed for road use. Which is why we’ll design our own custom junction boxes and power supplies.

Building your own cables and looms is a real asset. I’ll routinely build looms that combine a particular combination of cables, all individually assessed for length to fit the setup. The cables mean you can set up quickly and help ensure something isn’t accidentally pulled out of the back of a unit.

SOUND CHOICE

Andy: For a computer on stage it’s all about stability and efficiency. As playback and stage guys we try to avoid the use of third-party VSTs in a live setting. The soft synths that come with Live are low in CPU usage and they’re stable. We use built-in Ableton instruments like Analog or Tension.

The vocoder is from within the Ableton Live Analog synth. Hugo doesn’t use the MicroKorg’s vocoder live, but will use it to trigger Analog as the carrier synth. Otherwise he’ll use the MicroKorg as a controller synth of bass sounds. He’ll use the other controller keyboard for another sound in another octave range.

FINESSE & 1 PERCENTERS

To understand the job of Flight Facilities’ sound guys, you need to be thinking in terms of finesse, preparation and attention to detail, not big fader flourishes.

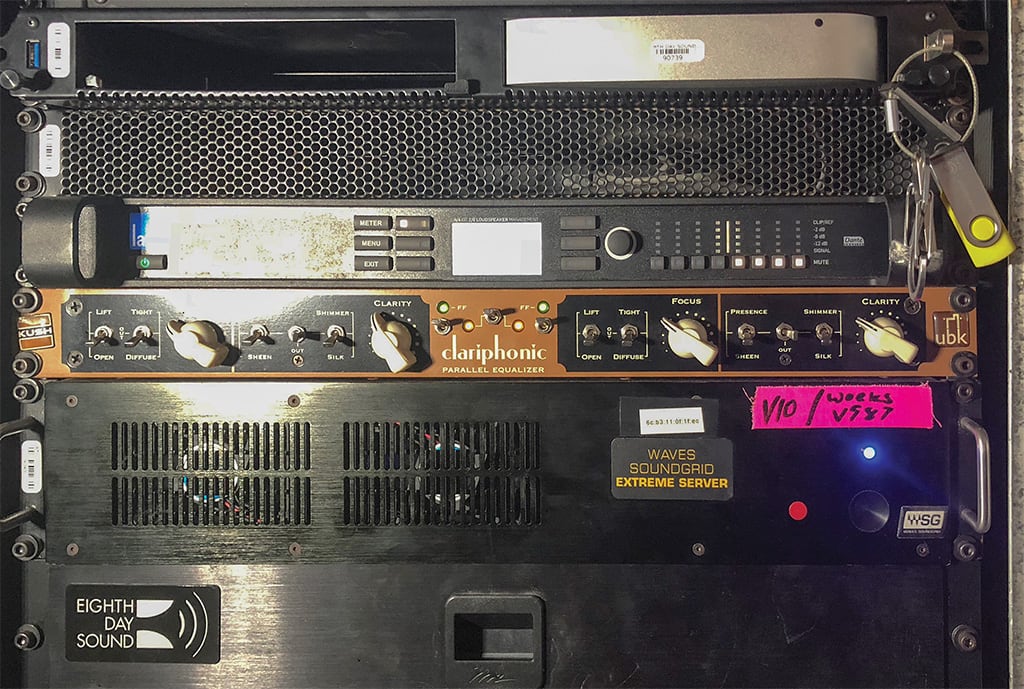

Fraser Walker describes production rehearsals as a great opportunity to get way beyond the meat ’n’ spuds of balancing levels and to dive into the one percenters. If there is one device that best sums up Fraser’s fairy dust approach to applying the extra-extra layer of piano gloss lacquer to the Flight Facilities mix, it’s his hardware Kush Audio Clariphonic Parallel Equalizer.

Fraser: The Clariphonic EQ is my secret sauce for electronic-style music. I run it over the master bus. The front panel doesn’t have frequencies marked on it — the guy who makes them doesn’t like getting hung up on frequencies, he’d rather you use your ears. But there’s detail in the manual. My ‘Focus’ control is set at about 1.4kHz. That’s addressing that ‘top of the snare’ openness. The ‘Clarity’ knob is set to around 32kHz. It’s a little like the silky ‘air’ band you’ll find on a Neve device or the Maag EQ4. I go analogue from the console (via an instance of Waves’ PuigChild compressor, which is just ticking over and an instance of Waves’ L1 limiter) into the Clariphonic, then analogue into the Lake processor and then AES out of the Lake or analogue depending on the venue. Sometimes I’ll tweak the Clariphonic mid-show when we have a full house and high humidity, just to restore some of that ‘air’ in the mix the bodies are soaking up.

The Clariphonic is a luxury I’d not necessarily have in a live band situation. (Saying that, on a different show, I might put it on vocals and turn that 58 into a Neumann condenser with the Air band.)

For a gig like Flight Facilities I’m not spending my time putting out fires. My job is more about getting the most out of the PA and the venue on the day, or if we’ve got noise limits then it’s about massaging the system output to retain energy in the room without being shut down.

RESPONSES