Dying For Analogue

A 13-year-album recorded and mixed entirely without plug-ins, automation or instant recall. D’Angelo might be calling for a Black Messiah, but is engineer Russell Elevado the saviour of analogue, or a martyr paying the price for his craft?

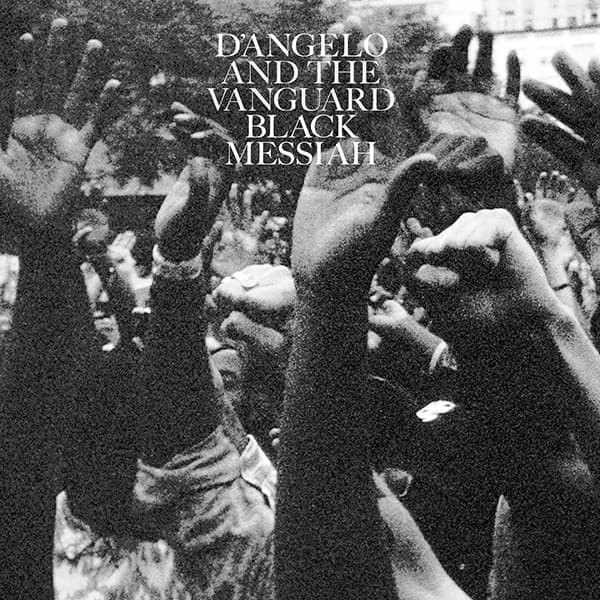

Artist: D’Angelo

Album: Black Messiah

The liner notes of D’Angelo’s third album, Black Messiah, contain the following striking pronouncement: “No digital ‘plug-ins’ of any kind were used in this recording. All of the recording, processing, effects and mixing was done in the analogue domain using tape and mostly vintage equipment.”

It should probably be unsurprising the politically-motivated artist draws distinct lines between things as arcane as analogue vs digital technology. But the sentiment common in the nineties — when many were convinced of analogue’s superior sonics and resisting the digital revolution by battening down control rooms and locking up their Fairchilds — is eye-catching for its rarity these days. Digital got its act together with the arrival of 24-bit resolution, the maturity of DAWs, and when capable AD/DA converters became the norm, forcing the analogue versus digital war to retreat to smaller battlefields. Almost everyone agrees that today’s pro audio digital recording gear sounds as good as analogue chains. Add the obvious and overwhelming practical advantages of DAWs and its small wonder analogue-centric facilities are on the endangered species list.

HOLD THE PHONE

On the phone from MSR Studios in New York, Russell Elevado, the main engineer and mixer on Black Messiah, explained why he and D’Angelo steadfastly stick with the dwindling camp of analogue diehards, and why Black Messiah wears its anti-plug-in stance as a badge of honour. Even the word ‘plug-ins’ is in quotation marks, as if describing something suspicious held aloft between the fingertips of one hand, while holding your nose with the other. But why would anyone not want to use any plug-ins on a mainstream album released in 2014?

“Primarily it’s about the sound,” began Elevado. “Analogue just sounds better. I feel even more strongly about that now than I did a few years ago. Digital sounds okay, but I still don’t like the workflow — I hate mixing in-the-box. All the great albums I’ve done were mixed on an SSL, using SSL automation. In recent years I’ve had to get used to doing automation in Pro Tools when I’m working on a smaller console with no automation. But I will not compromise on using a desk.

“I get the argument all the time that the new generation of plug-ins sound as good as the analogue gear they emulate. My reply is that over the years I’ve invested a lot of money in some of the best vintage mics and outboard, so why would I buy a plug-in package that might or might not be obsolete in a few years? My gear will never be obsolete, and I don’t need to get a plug-in of it. I have the originals!

“Some also argue that what you record ends up on CD or a lossy format anyway, so why not use plug-ins as it’ll make a recording project easier and cheaper. I call myself an ‘analogue gypsy’, because every time I go to another studio, I pack my gear into my car. It may take two or three trips and a few hours to set up, because I don’t trust anyone to transport my gear… that’s how committed I am to the sound. When I get requests from people who want me to do something for them on a more limited budget, I tell them I’m happy to think through solutions with them, but I can’t give them what they want unless I can use my gear and mix on a desk.

“I encourage people who want to work with me to make decisions based on a ‘final mix’ mentality. So once we leave the studio, there’s no need to go back and change anything. It’s about commitment. For me to revise a mix, it requires paying for studio time and manually recalling settings on outboard gear and the console. The only concession I make is that I’ll print instrumental and a cappella versions of the mix, to give people some options. I’ll only print stems on rare occasions; no one has the right to do recalls of my mixes. For me a mix is like a sculpture. Once a sculpture is done, it’s unheard of for someone else to take a chip off it. My approach is very old school. Luckily there are enough people willing to accept my way of working, and they’re usually very happy in the end.”

OLD-SCHOOL PRINCIPLE

So far so principled, and to add serious weight to his pro-analogue arguments and old-school methods Elevado can point at a glittering career, recognised with a whopping nine Grammy Award nominations (for his work with The Roots, Al Green, Roy Hargrove, and others) and five Grammy Awards (twice with Alicia Keys, Erykah Badu, Angelique Kidjo and D’Angelo).

Elevado mixed D’Angelo’s debut album, Brown Sugar, in 1995 and was the sonic mastermind behind D’Angelo’s now-classic second album Voodoo (2000). Also recorded and mixed entirely in the analogue domain, it’s become the most influential and critically-acclaimed album of the neo-soul genre. Expectations were sky high for the follow-up, but no one, least of all Elevado, could have foreseen that the making of Black Messiah would take a whopping 13 years.

Black Messiah’s gestation is matched only by Guns N’ Roses’ notoriously drawn-out comeback Chinese Democracy, which took about the same amount of time and $13m of Axl Rose & Co.’s cash. The final budget is likely to be significantly lower for Black Messiah, but multiple studio lockouts ranging from a couple of weeks to several months will have pushed the final tally to well over a million dollars. An article in the New York Times quoted D’Angelo’s tour manager, Alan Leeds, as saying: “25 accountants were still trying to figure it out, and none of them agree.”

Everyone uses a laptop these days, but D’Angelo insists on bringing a Studer A827 into his hotel room!

REVISIONIST HISTORY

While studio time isn’t cheap, for much of Black Messiah’s recording, the only person in the studio with D’Angelo was Elevado, both of whom remained impressively tight-lipped about what they were up to. Reports did circulate that work was impeded for a number of years by D’Angelo’s drug and alcohol issues, and The Roots drummer Questlove leaked a track in 2007 (as a result of which the two fell out), but that was more or less all that was known, until the album’s unexpected release last December.

Over our two long phone conversations, Elevado sounded relieved to finally spill the beans on the project. Even if it did mean reliving some of the album’s serious challenges; like the vexing question of how to remain objective when laying out a mix on the board for the umpteenth time, with different mix versions sometimes spread out over several years.

“D’Angelo would come in and ask me for a mix version dated April 3rd,” recalled Elevado, “which we might have completed a couple of days or a couple of years before, and he’d notice if it didn’t sound exactly like he remembered it! He could focus on the most minuscule detail and would insist on perfecting it until all possibilities were exhausted. Sometimes I had to tell him that it was impossible to get any closer and he’d have to work with what we had. Because I worked on Voodoo, I knew it was crucially important to keep extensive and detailed notes. There were mixes on Black Messiah that we’d last put on the board 10 years before, and had to lay out again after all that time! I always had to be at the top of my game.

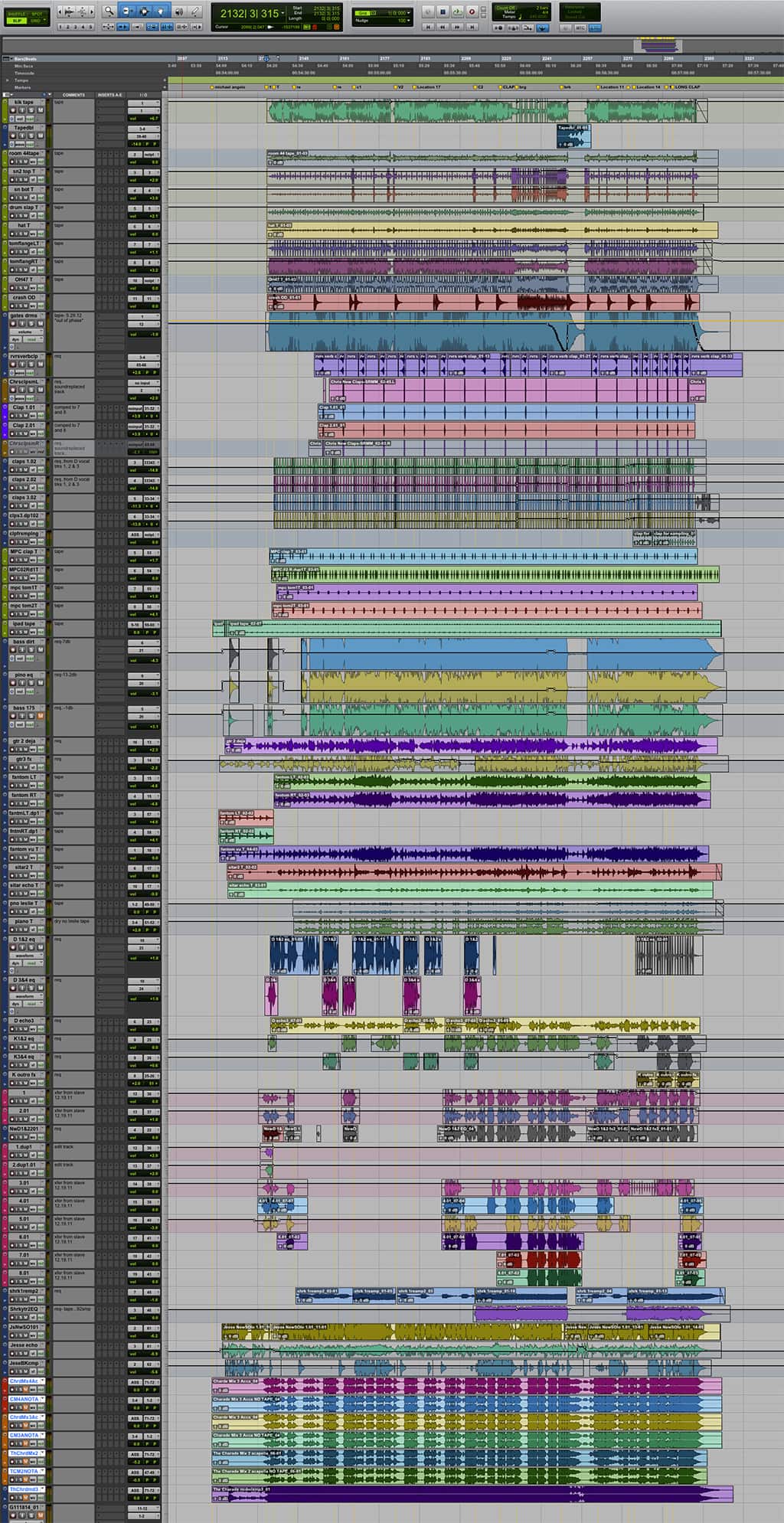

“To be able to keep our options open I would often have all 80 tracks of a mix session up on the desk, including some of the small faders, because there might be a 24-track vocal comp blend that could change at any time. I did not dare to print a comp and use those faders for something else, sometimes for years! There were times when I’d print something and just hope I wouldn’t have to go back and find the individual tracks again, but Murphy’s Law dictated that D would come in and want to change something! On one song I had four takes of Questlove’s drums, and D had compiled a drum track from them. We kept that comp for probably a year, and then he suddenly said, ‘I want to find a new take of Ahmir for the first minute of the song.’ So I had to find a way to match those sounds, but we’d lost one of the recall sheets and in the end I could not pull it off. He had to live with it. That sort of request didn’t happen all the time, but it got crazy on a couple of songs.

“You might have been working on a song for years, and not have a clue or hint about a last-minute change he’s been planning all along that transforms the song. Meanwhile, he’s had it in his head for years! That could be frustrating.

“Some songs were technical nightmares. We’d done loads of sessions in several different places, with most songs going through a number of permutations, and there could be a thousand technical details swimming in my head. So when it finally came down to me finishing, it was a question of, ‘Okay, now where do I start?’.

“On an emotional level, mixing a song like Really Love, which he began in 2002, became increasingly difficult. How do you keep perspective when you mix a song more than 10 times, and how do you stay in touch with the original vibe 13 years later?

“There were definitely moments during this project when I felt things were getting out of control. Even though we operated in the analogue domain, everything was always virtual! There was so much to remember and document, and we had such an unstructured way of working that at times I was quite uneasy about whether the final result would be up to scratch, especially when I really started digging in with the final mixes.”

RECALLING 13 YEARS AGO

With endless changes, permutations and mix recalls of each song, if ever there was an album screaming out to be made with a DAW, it was Black Messiah. Given that Elevado tells other clients he only does a couple of recalls for each song, he conceded that the amount of recalls he was doing with D’Angelo definitely was, “ironic. Had everything been done in Pro Tools, each change and recall would have been instantaneous.

“The earliest studio sessions for Black Messiah took place in 2001, right after he came off the Voodoo tour. The first studio we worked at was Sear Sound in New York. It was a crazy time. D was definitely ready for experimentation, and he was really into the black rock thing, like Jimi Hendrix, Parliament Funkadelic, Sly Stone and psychedelic music from The Beatles and Led Zeppelin. There was an element of him experimenting with drugs in the way his heroes had during their classic recordings.

“After Sear we bounced around between different studios; Avatar in New York, and two studios in the San Francisco area, one of them being The Plant Studios, and a few studios in LA like Paramount, and Henson for a while. Sometimes we were in a studio for a couple of weeks, sometimes much longer; we worked for a couple of years in total at Avatar. Then in 2007, D signed to J Records, which is part of RCA, and we got a new budget. Following that we spent a few more months in San Francisco, and then a number of studios in LA again for several months. Finally we came back to New York in 2010 for the home stretch. For the last three and a half years we were mostly at MSR Studios working pretty much full-time on the album — more than all the previous years combined.

“Although the focus on mixing became stronger towards the end, I had been mixing throughout the project. D likes me to get things in shape so he’s inspired to do other things. The very last year we were in mix mode all the time, with us going to and fro between MSR Studios A and C, which both have SSL desks. Ben Kane was very involved by this stage as well. He started out as my assistant at Electric Lady Studios, a couple years after Voodoo and eventually he started engineering sessions for D’Angelo when I was out of town or working with other artists. He was my right-hand man during the project and has a mixing credit on The Door. He was invaluable to me.

“Voodoo had to a large degree been collaborative, but on Black Messiah D really needed to experiment, get things out of his system and just craft songs all by himself. Though that changed after the 2008 LA sessions — when D was jamming with James Gadson drummer and Pino Palladino bassist — which Sugah Daddy came out of.

“He had started breaking the ice with Ahmir and in 2011 they started working together again. The Charade, Till It’s Done (Tutu) and Another Life came out of D and Questlove jamming at MSR, after which they were joined by Pino. While we were in New York we had quite a few people coming in adding new parts. For example, Quest replaced the drum machine on Really Love from the very first Sear sessions, and eventually his parts were replaced by James Gadson. This went on all the time. We also recorded sketches for many songs that weren’t released. You can’t imagine how many reels of tape we used!”

REEL LIFE

Apparently the answer is about 200 reels of 24-track tape made by Quantegy and ATR. With one reel of two-inch tape costing US$300 or thereabouts, just the tape budget would have topped the recording allowance for most of today’s mainstream albums. However, while Voodoo was exclusively recorded with tape, without a DAW in sight, Pro Tools did get a guernsey on Black Messiah. Elevado explained why it became inevitable — despite all their articles of analogue faith — to use some good old digital technology: “Up until 2010 I was using only tape, with Pro Tools purely for backups. Most of the time we ran two Studer A827s together, so we had 48 tracks running. I’d also transfer stems to slave tapes and record on them. For example, D’Angelo recorded all his own vocals to 24-track slaves that I’d loaded with music stems. He started doing that in the middle of recording Voodoo. I showed him how to run the tape machine, and he sat alone with the remote control in front of him, sometimes in the control room, sometimes in the live room.

“We set up a little mini studio for him, with the tape machine and a vocal chain of a Neumann U67 or U47, going into a Neve 1081 or 1073 preamp and a Teletronix LA2A. He also had a little Mackie board for monitoring, so he could pull up the tracks he wanted from the tape. He doesn’t like other people to be around and he does a lot of vari-speeding with tape the way George Clinton and Prince used to. He’s so used to it, he’s in his hotel room right now doing some vocal overdubs using my Studer A827 24-track. Everyone uses a laptop these days, but D insists on bringing an A827 into his hotel room!

“It shows how committed D is to using analogue tape. I’m the same, but by 2010 I became afraid we were losing something by playing the analogue tapes back too often. So with some of the older songs we started working off Pro Tools, purely to preserve the original tape recordings. We tried to stay on tape as long as we could, but in the end we were always surpassing 48 tracks, and the most efficient way to handle that is to use Pro Tools. Trying to sync up three or four tape machines is cumbersome! There were a couple of songs on Voodoo I had to rent a third tape machine for, and the mixes took forever because it took 10 to 15 seconds for the machines to sync after I hit play!

“After 2010, we still always went to tape and the choice take was transferred to Pro Tools. If somebody came in unexpectedly and wanted to immediately do an overdub, I would record in Pro Tools, just because it was faster. Then right afterwards I’d bounce it out to tape and back into Pro Tools. 100% of tracks on Black Messiah touched analogue tape at some stage or another. Analogue tape definitely adds a colour, but most of all it adds depth, that’s the biggest difference. There’s a front and back to the sound image in analogue, as well as top and bottom, and left and right. It’s a spatial thing.

“I work at 24-bit/88.1k in Pro Tools. There’s a big difference between 16 and 24 bits. We did try Pro Tools on Voodoo, but the sound of the 888s was atrocious. Even ADATs and the Tascam DA88 sounded better than Pro Tools at the time, because they were using better chips! Apogee convertors were an option but you had to rent them and they were expensive. In fact, you had to rent a Pro Tools ‘rig’ in those days as they were still not a studio standard. Can you imagine me paying to rent Pro Tools! But today’s higher quality clocking and converters make a big difference, and higher sampling rates are essential if you’re using plug-ins. But even then, the moment you start using several plug-ins, things start sounding weird again, because plug-ins are not processing things in the right way. You’d be surprised how much character you can add simply by re-amping things instead! So we used Pro Tools purely as a multitrack machine and storage medium, without any plug-ins.”

How do you keep perspective when you mix a song more than 10 times, and how do you stay in touch with the original vibe 13 years later?

A CLASS SIGNAL PATH

In the context of Elevado’s pro-analogue/anti-plug-in convictions and dedication to the tape medium, you’d expect him to be fanatical about recording signal chains. But he doesn’t seem too bothered, provided he uses any of his own vintage and Class A pieces of kit, that is, or something equivalent if he’s in another studio. Though sometimes they might be hard to find.

“When I started making money, I began collecting gear that could give me different textures and colours,” said Elevado. “Rather than surgical tools or gear most studios had. So I got vintage mic pres, compressors, EQs and effect boxes, and I also got into envelope filters and pieces that could bring out certain hidden timbres in instruments and would help me dismantle the frequencies and sounds of any type of instrument I came across. I now have things like an original Gates Sta-Level compressor, which I had modified; the Gates SA-39B limiter; one of my favourites, ‘The Bomb’ I call it, a crazy mono Altec tube compressor that has about 25 tubes; and other modified Altec compressors, like the 436c and 438c. I also have an LA2A, UA 1178, WSW 601431A, Dynax and Fairman TLC compressors, and my EQs include the Quad Eight MM-312, 712 graphic and 333c, Neve 33115, Helios Type 79 and Telefunken 395As. Plus I have reverbs/echoes like the Fulltone Tube Tape Echo, Roland Chorus Echo SRE 555, Maestro Tape Echo and Demeter Realverb, and many vintage and new effect pedals from Mutron, Maestro, Mooger and so on.

“I also have tons of mics, like a Neumann U47 I paid US$7000 for back in the ’90s that looks brand new and sounds incredible, and a matched pair of U64 tube mics. My mic preamps include a vintage Altec 9470a from the designer of the Langevin AM-16, plus Neve, Quad Eight, Telefunken 676A and the Siemens V276. In many cases I don’t mind what preamp I use, as long as it is one of the latter three. I used to be pickier, and I’d love to say that for this album I was mostly using Neves, but all these mic pres are of high quality, and I might get a little surprised one day when I have the Telefunken on the snare, instead of the Neve. They’re all good. It’s like having three different Ferraris to choose from. When you get to that level of mic pre with that kind of character, you could be using anything, so I don’t have a go-to mic pre anymore.

“I changed my signal chains once in a while, but for drums they would have for the most part been a Neumann FET47 on the kick, sometimes with a secondary mic like my AKG D12 or Electro-Voice RE20. The snare would usually have an AKG C451 on the top and a Shure SM57 on the bottom. I’d occasionally swap them for the harder stuff, with the 57 on the top and the 451 at the bottom. I find that if you swap the mics, you instantly get that rock sound. I usually have just one mono overhead, a U47, but I will use an AKG C24 or a pair of U64s if I need to cover more cymbals that might be spread away from each other, and I have Sennheiser MD421s on the toms. I use many different room mics depending on the room and the sound and texture I’m after — they could be an RCA 44 or 77DX, Beyer M160, or Neumann U47 or U67.

“Some of the bass sounds on the album came from D’Angelo’s Ensoniq ASR10 synth, which I DI’d. I usually record the bass cabinet with a FET47 going through one of my main three mic pres, and then a compressor like an 1176 or an LA2A, but also sometimes a Gates, Altec, or UA 175. On Really Love Pino played a semi-acoustic bass with flatwound strings, and I tried to make it sound a little bit like an upright. The classical guitar on that track is played by Mark Hammond, which I recorded using a U47 without compression. I only really use a compressor in the recording chain for bass and vocals.

“I also had either a U47, 421, SM57 or combination of those on the electric guitar cabinets. I recorded D’s acoustic piano with the AKG C24 they have at MSR, or if that’s not available, a pair of KM56s or U67s. I like using tube mics on the piano. Though it helps when you have a good player, and D is an amazing player who really owns the instrument. In addition to playing guitar and piano, he programmed a lot of drums on an Akai MPC2000 using samples from records and samples I’ve recorded, as well as the Ensoniq KT-88. But 90% of the synth sounds came from his ASR10, which he’s used since his first album.”

ANALOGUE DIES HARD

Clearly, the making of Black Messiah was an epic journey for Elevado and D’Angelo. But any fears that the 13 year time span would only return stodgy and overcooked work proved unfounded. One critic amongst the cavalcade of effusive reviewers, Joe Goggins of Drowned In Sound, noted, “Like Voodoo, Black Messiah’s greatest strength lies in D’Angelo’s understanding of how to create mood by weaving an impossibly complex instrumental palette,” and that “everything from D’Angelo’s voice to the crackle of the snare is treated with a delicate mastery.” The master over the weft and warp of Black Messiah’s fabric was Russell Elevado. He’s managed to make Black Messiah sound truly great. How much this is due to D’Angelo’s and Elevado’s commitment to the analogue medium is a question that no-one who truly cares about good sound can afford to ignore.

RESPONSES