DIY: Don’t Be A Tool

Self-sufficient DIY musician, Nick Zammuto, built his house, his studio, and a catapult, but not his music gear. Why? He wanted to use tools, not be one.

Artist: Zammuto

Album: Anchor

Taking in Nick Zammuto’s surroundings is enough to realise DIY isn’t merely a penchant, or even just a necessity, but a way of life. Nick, his wife Molly and their three boys are homesteaders in the sparsely populated state of Vermont, just south of the Canadian border in the US’s New England region. Eight years ago, he and Molly moved into a shack on the property while he slowly built a house to accommodate their growing family.

It was a new chapter in their lives, and the mortgage on the barely-liveable property was cheaper than renting Molly’s barely-liveable Brooklyn apartment.

The general rule for budgeting the build was ‘no contractors’. If they couldn’t build it themselves, it wouldn’t get built. So with copies of Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language and Scot Simpson’s Complete Book of Framing under his arm, Nick taught himself how to build a staircase and guesstimate the angles of a multi-faceted roofline. Now, well and truly settled, Molly’s veggie garden sustains the clan, and Nick makes music under the Zammuto moniker out of a converted tractor garage a short walk from the house.

NOT BY THE BOOKS

Art imitates life pretty consistently for Nick. Like his out-of-the-way home, his music is also a little bit off-centre. So working in a big studio was “never really a possibility,” he says. It’s never really phased Nick, though, he loves getting his hands dirty, figuring out how to create things from scratch. He’ll wax lyrical about a new saw blade ripping wood like a knife through butter as eagerly as he’ll detail his sound design hobby of scratching beats in a record’s locked groove. He just has an innate sense for DIY.

Previously one half of the critically-acclaimed sampling duo The Books, Nick would dig into the archives for sounds like a snuffling pig unearthing truffles with the dirt still attached. He was an analytical chemist in an art conservation lab, so giving old material a new lease on life was a specialty. They would create digital collages using the euphonic juice from old vinyl, VHS and audio tapes to give their sampled creations more flavour. Because each sample came with its own sense of space and time attached, the records were essentially mixed ‘dry’.

Zammuto’s latest record Anchor is the next step in Nick’s development as a producer. It’s his second full-length album since starting the solo project, with one of the main differences to The Books being he samples himself more than other sources. It’s meant he’s had to re-educate himself on how to give his recordings their own character — ‘dry’ wasn’t going to cut it anymore.

“I eschewed reverb for so long because I didn’t want the music to sound like it was in another room or in another space,” said Nick. “I really wanted an immediate, crisp surface to things. But I think that’s only because I never really had access to good reverbs. I was always working with these crappy digital reverbs that didn’t sound very good. Now that I have access to some beautiful old spring reverbs – they’re instruments in themselves.”

He’s been collecting a handful of reverb units over the years, starting with the Lexicon PCM81: “I love the old 16-bit effects units. It’s just got that classic sound and if you put it on an aux channel it never gets in the way. It’s always in the correct position.”

One of his more prized pieces is a rack-mounted Tube Works RT-921 Real Tube Stereo Reverb: “It’s got six springs on each side. You can drive the preamp tubes as hard as you want, and that feeds the reverb. Then you can control the colour of the reverb afterwards with a three-band EQ. It’s an amazing sound. I tried to use the spring reverb in my guitar amp for a while, but it always added that guitar amp colour.”

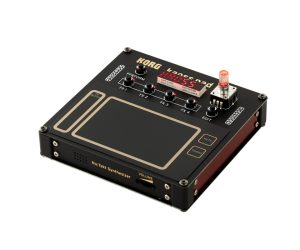

For mono sources, he often turns to his Vermona Retroverb Lancet: “It’s basically a three-spring reverb inside of a little desktop unit that’s got a multimode filter attached to it. It’s just perfect on kick drums to give it that vintage awesomeness and any kind of guitar or bass sounds amazing through it.”

Although the reverb obsession is a relatively recent career development, he’s always been interested in the minutiae of sounds. It’s a by-product of staring down a microscope much of your life — you get obsessed with the details. So when he buys gear, he buys it for those kinds of reasons. For instance, he uses his Kush Audio Elektra analogue stereo EQ not just because he believes it sounds superior to digital EQ, but because he can turn up needle-shaped parametric mid-bands and pull out different transients on the left and right to really widen his drums out in the stereo field.

“For some reason I feel language is like a full frontal attack on my cortex, and it never really gets through,” explains Nick. “I think that’s true about a lot of introverted people, the direct approach is blocked off. So I’m trying to make music where the centre is this kind of mystery, but the periphery is really the way in. So a good sound to me is when you hear the crackle of the recording as much as you hear the subject of the record. It can transport you to this magical place when it’s done well. That’s the quality I’m looking for, something that makes a sound un-nameably… interesting.”

My goal is to use tools without becoming a tool. I love the idea that a tool designed for a particular purpose, can be used for something completely different

OVER SAMPLING

The way Nick works is to create a sample library of his own playing from which he can pull the best elements in a similar curatorial process to the one he’s been using for years. “When I record an instrument, I’m sampling it in a way, because post-production usually completely changes the intention of the original recording,” he explained. “I over-record everything. I have about an hour-long take for every three seconds that ends up on the record. So there’s a lot of fine tuning that goes into pulling the right moment out of a recording session.”

One of those libraries he’s built up is made of beats created by scratching notches into the locked groove of records. He divides the circular groove into beat divisions, using a protractor to mark the record’s label: 90 or 45 degrees makes 4/4, and other divisions of 360 degrees result in different time signatures. Then by scratching with different implements he can get different percussive sounds — a thumb tack renders a bassy thump, a razor blade more of a snap, and sand paper gives an effect like maracas. Scratch inwards and the sound pops up on the left, scratch out and it’s on the right. He’s made hundreds of these one-time beats, and used one of his favourites, a 9/8 loop at the beginning of the song Great Equator.

Other times he’ll sample a real life drummer, mostly Sean Dixon, the skins player for Zammuto. The two nerd out on polyrhythms, and Sean will often play for an extended period, while Nick moves noisemakers around the kits, like splashes on the snare and nut-shells on the floor tom. He’ll also tweak delays and reverbs on the fly, looking for gnarly intersections of feedback and drums looping on themselves that he can sample later. He records it all to multi-track generally using two AKG C414s as overheads in the Recorderman configuration, with an Audix D6 on the kick, a Sennheiser e604 on the snare top, and Audix i5 on the bottom, with another e604 on the floor tom.

“I’d always just sampled drums,” said Nick. “I’d never tried to play them or record them on my own. So when I first got a drum kit, my early recordings sounded like crap — they were all phasey and weird, and had no power. I was like, “How do they do that?” And started doing some research on that. That’s where I came across the Recorderman setup — trying to figure out how to get really close-mic’ed drums that didn’t have phase issues on the snare.

“I’ve always liked Stewart Copeland’s drum sound, really loud in the mix and still have it work. He has a clean, clicky style where the hi-hat is way louder than it should be.

“I love that trick with the snare where if you record the top and bottom then EQ the recordings of the top and the bottom as close as you possibly can and pan them hard left and right, you get this really, amazingly vivid snare sound.”

HURLING THE HP

Nick still uses Sony Acid as his DAW. It was the first program he used, and the cheapest one at Guitar Centre at the time. Having used it for so long, he just “thinks and stuff happens in Acid, the interface just completely disappears. And it sounds like PCs look in a lot of ways — boxier and edgy. I find that Ableton sounds more like Macs look — things get rounded a little bit and glossy.” But the real feature that keeps him coming back is the ease in which you can re-pitch tracks in the timeline. “You can cut out one note in the middle of that guitar take and then press the plus and minus keys to re-pitch it by semitones. It’s tremendously useful to be able to work really fast in a melodic way. I’m generating a lot of interesting melodies by taking a single note, making several copies and re-pitching it right there.”

For the music video to IO — a catchy off-kilter, ’80s-tinged pop single from Anchor about getting catapulted into shit jobs, inhibiting self-actualisation — Nick built a huge catapult. Technically’s it’s actually a trebuchet, which is “even better for flinging shit,” he says. On the video, one of the feature pieces hurled from the trebuchet was an ageing HP desktop. It had been the brains behind much of The Books’ catalogue but had reached the end of its life. So he did the one thing we all dream of doing when our computers die, he catapulted it. Nick: “There was something really cathartic seeing that fly hundreds of feet up in the air.”

His relationship with computers isn’t as strained as it might seem, but he keeps them at more of an arm’s length then he did with The Books. “I think of them as having perfect memory. They’re a great extension to my own memory which, having three sons, is a little bit patchy sometimes. So if you’re looking for that crisp, clean perfection, they do the job every single time. They’re not particularly good at controlled chaos which is another big element of what I’m interested in. So I like having the best of both worlds, to be able to take this analogue world, crystallise and fine tune it, and if needs be, send it back out into the wires and work with it some more.”

One of his tricks that uses this digital/analogue dichotomy to advantage is when he processes time-stretched sounds back through his analogue reverbs. Nick: “I like the idea that time in a DAW is arbitrary. If you take a sound and speed it up an octave so it sounds like a chipmunk; send that through the reverb of your choice; take that recording and pitch it back down the same amount you pitched it up before… then the vocal will still be there in its original pitch but the decay tail is buttery, twice as long, and takes forever to work itself out. Plus, you lose the top octave of the high end in that process, so it really brings out the dark, broody character of a reverb tail. I find it works particularly well on spring reverb because there’s this weird pulsing chaos in those tails.”

Once he’s done this external pass, he often recombines it with the original vocal to preserve the top end. He also uses different pitch intervals, and sends the vocal in reverse. Once it’s back in the computer, he might even re-pitch the reverb tail again… anything goes with Zammuto, including hard panning bass. It’s generally perceived as an engineering no-no, inherited from the days of vinyl where errant low end could throw the needle out of the groove. It didn’t stop him doing it on Need Some Sun, and the vinyl pressing still managed to cope. “The vinyl pressing of that track sounds really good,” said Nick. “Even though there’s very different bass on the left and right channel, somehow the needle is equally confused in both directions. It sits there nicely.”

I’m trying to make music where the centre is this kind of mystery, but the periphery is really the way in

NO DIY TOOLS

Nick is a DIY handy man, and an exceptional one at that — as the house, the studio, the farm, and his laser Bass Projector musical sculptures attest [see sidebar]. But he draws the line at building his own audio gear; even though DIY electronics would seem to sit more comfortably in the playground of someone with a university science degree than a drop saw and a hammer. He’s got a phrase for it: “‘Don’t be a tool’ — my goal is to use tools without becoming a tool. Building my house was all about the tools. Like getting a decent saw that can actually do the job you want it to do. Working with lousy tools, it’s kind of a ‘shit in, shit out’ situation. There’s something beautiful about a brand new saw blade, just the way it turns wood into butter. Certain pieces of sonic gear have that same feeling — everything you put through them becomes magical.

“I love the idea that a tool designed for a particular purpose, can be used for something completely different. Whether you’re building a weird-shaped house or trying to work on music that’s a little bit left of centre. It’s that sense of endless possibilities you get, particularly from analogue gear.”

His synths include a Dave Smith Instruments Polyevolver, a Nord and a Moog Slim Phatty. He also uses an Electrix Filter Factory, which allows him to do stereo filter sweeps, which he uses with an LFO to create swishiness in his cymbals, as well as a cheesy Mo’FX unit, which has a tremolo you can control via MIDI for some funky shape-changing in real-time.

It’s his sonic playground, completely distanced from the music industry machine both ideologically and geographically. The DIY route is paying off for this musician. When he’s not on tour he’s around his kids, his studio is away from the house so he doesn’t wake anyone up at night, and he’s not paying rent on an apartment anymore, let alone a studio in the city. He’s well and truly anchored, and he couldn’t imagine it any other way: “It really allows me to keep my overheads low which means I can make the records I want to make and keep going along this weird path in Vermont.”

RESPONSES