Deja Vu: Giorgio Moroder is Back

Thanks to Daft Punk, Italian stallion Giorgio Moroder is back with a new ‘totally Giorgio’ album. And he doesn’t care if it’s a hit… he’s had plenty of those.

Artist: Giorgio Moroder

Album: Deja Vu

It’s fitting that synthesiser guru, Giorgio Moroder, who always seemed to be in touch with the future, was plucked out of hibernation by two French robots with a cybernetic golden touch. On the merits of a single nostalgic monologue, Giorgio By Moroder on Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, even Red Bull — which wouldn’t sponsor anything less progressive than a symphony orchestra of rubber-band-playing trapeze artists — was suddenly backing the septuagenarian, who’s last hit was in 1998, as the next big thing to hit the DJ circuit.

To be honest, even 1998 is stretching it a bit. It was the year he took out the inaugural Grammy for Best Dance Recording, sure. But the song that won, a reunion number with Donna Summers called Carry On, was actually released in 1992. It only scraped into the award year courtesy of a remix that charted. The last time Moroder personally made a dent on popular culture was over 20 years ago.

Moroder’s composition/production credits dried up around the time when hip hop started to dominate the charts. Although personally unable to translate his knack for four-on-the-floor disco into currency on the urban scene, his work was regularly referenced by those that knew how to weave with it. Even Beyonce’s Naughty Girl, her introduction to the world as a solo artist, begins with that sensual come-get-me line from Donna Summer’s orgasmic hit Love to Love You Baby. And Beyonce wasn’t the only one. With such a wide body of work that covered the dance floor to movie soundtracks like the Academy award-winning Midnight Express, Top Gun, of course, American Gigolo, Scarface, and Flashdance, he painted a path for everyone from Katy Perry producer Dr Luke to Hans Zimmer — who named his Dark Knight Rises modular synth Giorgio.

But here he was in 2014, the Moroder name was starting to reclaim its popular culture cachet, and Giorgio was loving it. Sure, it wasn’t the high-riding ’80s notoriety that landed ‘Moroder’ on the hood of an Italian supercar, but name-drop worthy, enough to sign a record deal. The result, Deja Vu, his first solo album in 30 years.

HIT RECORD

Producer Michael ‘Smidi’ Smith has been a regular collaborator with Moroder for the last decade. The two met when Smidi produced a band managed by Moroder’s wife, Francesca. And with Moroder living in Westwood, just 10 minutes drive from Smidi’s LA production studio, he’d regularly pop by the studio to work on new material like remixes for Haim and Coldplay to drop into his DJ set of ’70s and ’80s classics. As the opportunities kept rolling in, Moroder started to get a sense things might be on the upturn. “He was retired,” said Smidi. “Then after the Daft album hit, he was like, ‘well, shit, I’m supposed to be done, but now I can work again.’” He kept telling Smidi to be ready, if a record deal came his way he was going to take it. In the end, it was Sony who came to the party.

“Whether this one wins a grammy or not wasn’t a concern. He didn’t care,” claimed Smidi. “He wanted to make a record again, not a massive, successful statement. He was just having a blast.”

I want to feel really attached to every single song, like it’s the most Giorgio version of everything

VOCAL PITCHES

Smidi’s studio is just a mile from Venice Beach, its big bay windows letting the Californian rays soak into the main rehearsal/tracking space and control room. It’s a setup tuned to a modern style of production: DAW at its centre, room to experiment, and a healthy smattering of unique pieces like Studio Electronics’ ARP2600-inspired Boomstar 4075 desktop analogue synth.

The record is called Deja Vu, but the recording process was anything but for Moroder. “When he did Donna’s records they’d cut several songs a day,” said Smidi. “They’d lay down maybe one or two passes, Donna would sing, no Auto-Tune, and it would be sent off to a mixer. They could make a great album in a week or two.”

By comparison, the vocalists on this record never made it into the same studio. The cast — including Kylie, Sia, Britney, Charli XCX, Kelis — all had their own production teams and busy schedules, so a two-week turnaround was out of the question. “So much of it was in the box,” commented Smidi. “A lot of the artists would be touring or in other countries. We’d be sending tracks back and forth and flying the files in. It’s collaborative, but compared to what it used to be, pretty time-consuming.” It’s a Catch 22; without the ability to phone in tracks, the guest list wouldn’t have been nearly as impressive.

Handing tracks over to production teams you’re not familiar with has its hand-wringing moments though. When Madonna’s record leaked, the team was closing in on the final album, and Smidi started getting paranoid. “Having so much in so many places — Dropbox, Wetransfer — really freaked me out,” confessed Smidi. “We tried to do what we could; no obvious ‘Britney Spears, here it comes!’ file names. Kylie’s track was the only one that leaked. You never know, it could have been somebody in marketing at the label. It worked out; she went to No. 1 in the Dance charts, and the timing with her tour was great.”

GIORGIO BY MORODER

The obvious question was, now the wheels were in motion, what would a Giorgio Moroder album sound like in 2015? “He didn’t want to make a retro disco record, like, ‘I’m baaaack!’,” said Smidi. “But also, not EDM. Something that still felt like him, where he’s coming up with a lot of melodies and lines, but with a combination of electronic and acoustic sounds. We used a lot of programmed stuff, but made sure we had live drums on a lot of it, and used real Rhodes when we could.”

Smidi functioned as the executive producer on Deja Vu, and on occasion had to edit down other producers’ tracks. Smidi: “Every song was completely different; the Kylie track Right Here, Right Now came in mostly done. Giorgio and the producer got it really close, and then we played with it.

“Giorgio likes to minimise. Some songs came in with too much going on. I mean, we all do it. We’d go through and find the parts that felt really great and pull others down or out completely.

“Deja Vu started out as a rough keyboard part that Giorgio sent to Sia. She wrote the top-line and sent back the finished vocals. Then we just sat and played everything; the bass part, the keys, brought in a drummer to do the drums.

“Most of the time we made it better. Or we made it more Giorgio. His intention was, ‘We’re making my record. I want to feel really attached to every single song, like it’s the most Giorgio version of everything.’ I’d go in and get a little more EDM, and he’d say, ‘That’s cool, but let’s try this.’ Then he’d sing a melody that was just so Giorgio and perfect.”

SYNTH UPDATE

While the songs were gradually made ‘more Giorgio’, the original sketches often started out with current-style programming — a punchy, strong EDM kick, same with the snare — and built from there.

“Any ’70s and ’80s synths would have been really out of place on this,” said Smidi. “We needed sounds that were a little lusher, bigger, hit a little harder, and had more shape in the chorus.”

Keeping the sounds firmly in the 21st century is Smidi’s reFX Nexus synth plug-in. As well as being a flexible synthesis and control system, it’s also a way to keep up to date with current sounds. The reFX boffins continually release packs that keep Nexus users in touch with the sound of their peers. Want that latest Armin Van Buren patch? Chances are he either dialled it up on Nexus, or they’ve since released an identical one.

On the analogue side, he uses a Studio Electronics Boomstar 4075, a little desktop analogue synth with the filter from the ARP2600. Daft Punk used a Yamaha CS80 lo-pass filter-inspired version called the SE80 in Tron. But despite the Daft Punk lifeline and synth similarities, there were no big Tron synth sounds on the album. “It wasn’t a conscious decision, he just wasn’t feeling it.”

Moroder has a reputation as a synth legend, but speed is also a priority. It’s not like Giorgio doesn’t know his sound by now. “We wanted to keep creativity moving,” said Smidi. “So we created a bank of sounds in Nexus that he liked in the past, and climbed in to build some custom patches. Then there’d be places to reach to quickly when thinking through melodic ideas and chord structure.”

Halfway through the record, Smidi dug in again to build more patches and refill the creative well. Smidi: “There was one sound he really likes that harks back to his old stuff. It’s an oscillated synth, with eight different versions you can easily control the gate length on. Some were doubled up, some were bright. You can just toggle through different textures quickly and find something close. We’ve used that on several songs and each time I’d say, ‘We can’t use it again!’ So we mixed it up a bit.”

DISCO IS OUT, BUT SO IN

While the lead tracks all have noticeable disco elements to them, it was a conscious effort not to dip the mirror ball too close to the rest of the album. “He didn’t want to bring in too much disco electric guitar,” said Smidi. “That was our biggest trick, to make sure it was in there on songs that needed it, but not completely driving it.”

“We tried to change the bass sound on each song. The bass on Right Here, Right Now was real barky, other songs had sub-bass to get out of the way of the kick, establish the chord group and let the synths carry it.”

The live drums were recorded at East West studios. But guitars were tracked at Smidi’s studio using a clean solid state amp with an AEA R84 ribbon, and a Shure SM57 or Sennheiser 421, all through Manley preamps. No Nile Rogers DI disco strat here.

While times have changed, as you’d expect, Moroder ain’t no luddite. In his apartment he keeps a neat home studio that lets him run with his creative impulse. On the Sia track, he had an idea for a group vocal. So he rounded up a handful of valets that worked downstairs and recorded them in his house, then cut it up and dropped it into the track.

MANNY IN THE MIX

Manny Marroquin mixed the Sia single Deja Vu months before the rest of the album. But when it came time to mix the rest, Smidi was advocating for Mitch McCarthy. “Manny is an amazing mixer,” enthused Smidi. “But I’d just finished a project with Mitch where he just destroyed it. He was so great to work with; a bad arse, humble, and so few revisions because he just got it. I told Giorgio, ‘We’ve got to use this guy.’”

Giorgio was initially hesitant. After all, you’d be crazy to think anyone else in pop is going to beat Manny to the punch. But Smidi was adamant and they eventually sent one track, which was followed by another, and another, until McCarthy’s Dropbox was full of sessions. Smidi: “He did everything except that Sia single, and a couple of instrumentals on the B side that Giorgio had mixed.”

FROM THE HORSE’S MOUTH

McCarthy shares Owl Foot Ranch Studio in Tarzana, on the edge of Topanga State Park, with a Canadian deep-house producer. It’s about “30 minutes from everywhere in LA,” reckons McCarthy. And like a lot of places in proximity to Hollywood, it has a history. This one? It’s the barn Mister Ed, the talking horse, used to poke his head out of. Which is cool on two levels. A good story to tell, and well, it’s a barn, in a forest, in the middle of LA. Clients don’t get that view very often.

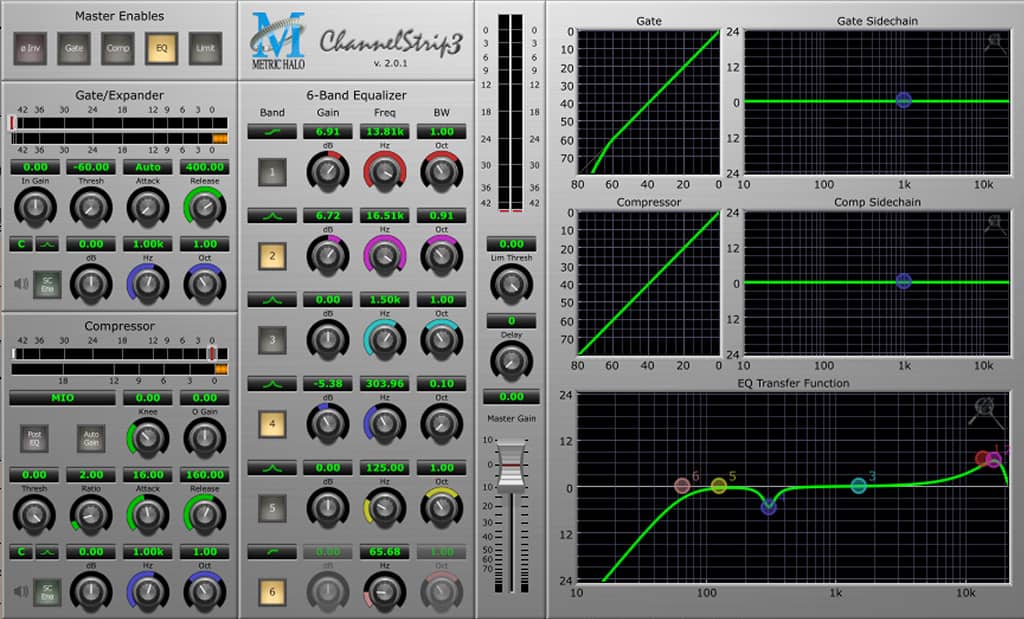

McCarthy only moved in about four months ago, and while he’s got a pair of old Tannoy mains in the wall, powered by an old Macintosh tube amp. He prefers to work on his Yamaha NS10s and switch to the Dynaudio BM15As rather than the mains. “I’m just not used to them,” he explained. “Everything is going through a Lynx Aurora 16 converter. I have a MacBook, the new Mac tower, a pair of dbx 165A compressors, and a pair of Neve 1073 pre/EQs.

“I limit my tools so I’m not all over the place. I only keep the UAD plug-ins I like. When you start to become busy, you can’t really think too much — like EQ the kick for an hour, which is a terrible move anyway. It makes you work more efficiently and trust your gut.

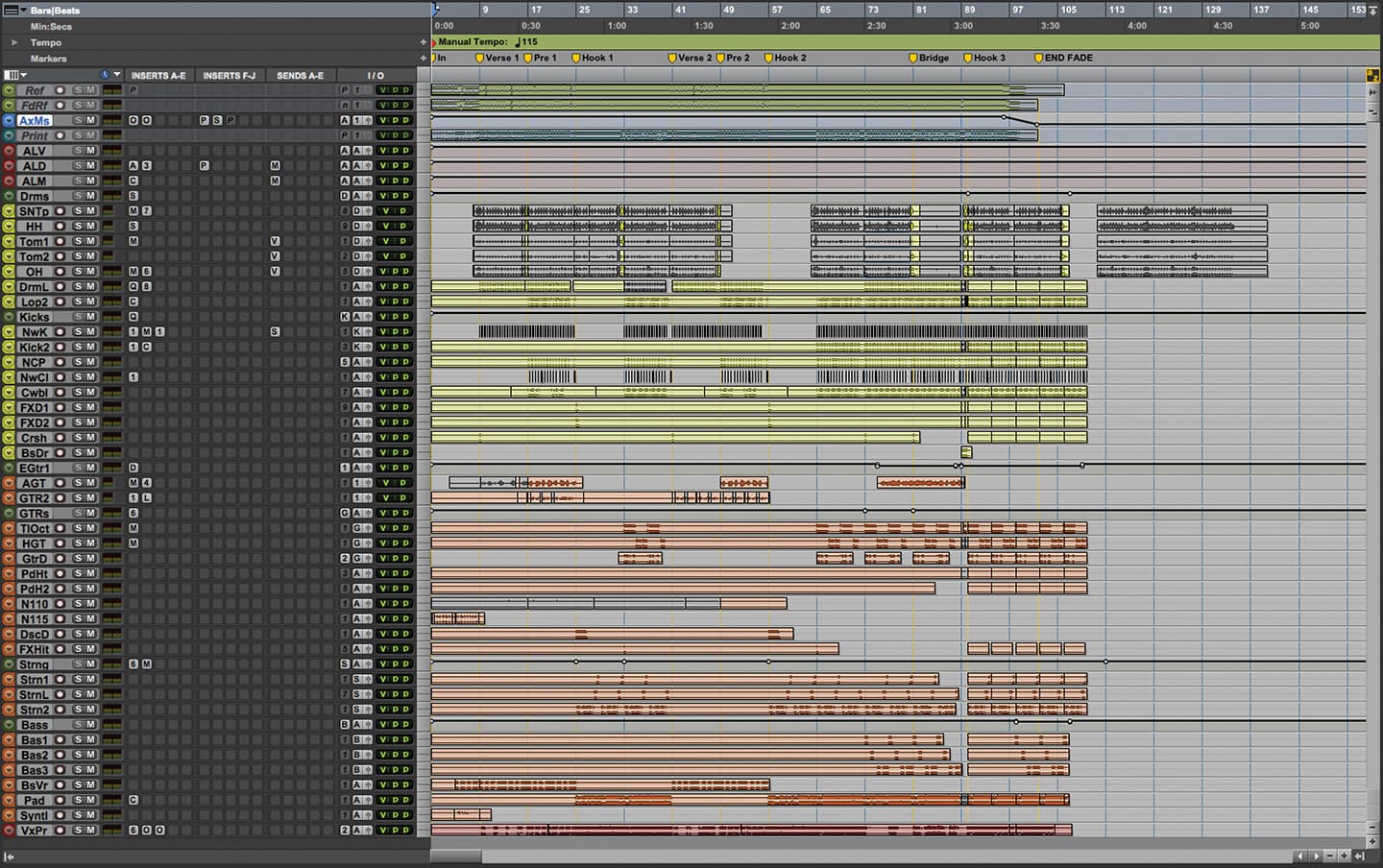

“I’m essentially completely in-the-box, because it’s the world I grew up in and I rely pretty heavily on UAD plug-ins to get the job done. I’ve worked on consoles, but this is just what I’m comfortable with. At the moment, I’ve got two and a half weeks to turn around a Melanie Martinez album, and there’s no way I’d be able to get it done if I was on a console. You’d probably triple the time just because of recall.”

JUST A MIX ENGINEER

Since moving to LA four years ago, McCarthy has built a reputation as a pop go-to man. He’d engineered for a long time, and decided he wanted to mix more. He started mixing almost every song producer Mario Marchetti worked on for two years, before he met his current manager, Ian McEvily from Rebel One. They were looking for a mixer to represent, but no one wanted to just be a mixer. Everyone in LA seemed to want to write or produce as well. Even now, there’s no Mixing category on Rebel One’s site. It worked out for McCarthy, who was suddenly thrust into the view of every producer on the roster. He still had to prove his worth on each and every opportunity, but learnt a lot about himself along the way.

“I would say that I don’t have a sound,” said McCarthy. “I just do what’s best for the song. Mixing is almost problem solving. I go off emotion as well, but there’s also things that need to be fixed.”

Which is just as much about knowing when to leave things alone, he reckons. “Some people automatically assume, ‘Oh, there’s a bass, I’m going to put an 1176 or R-Bass on it.’ But it may not need that. You just need to listen to the source. A lot of pop producers send me Logic stems that are already processed. When I throw it in ProTools, it sounds exactly the same as the rough mix. That’s my approach; send me where you left off, and I’m going to take it to the finish line.”

MASTERING IN YOUR SLEEP

The chain of references went one step further. McCarthy had also been working with another audio professional who was ‘killing it’, Australian mastering engineer, Matt Gray. The pair had met working on a track for producer/writer CJ Baran (Cody Simpson, Mika, signed with Max Martin), who’s been sending Matt tracks to master since he was in his teens. McCarthy, who’s sent masters to every house in LA, said Matt gives it “that final touch I hear in my head. For whatever reason, my mixes translate with what he does. It’s important to have a solid team of people I trust. We just have a great relationship; no ego, just great communication.”

McCarthy doesn’t slam his master bus, preferring to leave 4-5dB — “the magic number” — of headroom for Matt to get creative with. “I put a Fab Filter Pro Limiter and Slate FG-X limiter on my master bus, but that’s just for sending clients reference mixes. There’s no compression on Right Here, Right Now other than a bit on the drums, and 1.5dB of master bus compression with the Shadow Hills plug-in. All the pop samples are so compressed and processed already, why would you put another compressor on them?”

When it came time to passing on the baton to Matt, he was literally sleeping on the job. Over the other side of the Pacific, the ball was rolling — Mitch told Smidi he wanted Matt, and Smidi did the job of convincing Sony — but Matt had no idea. He went to bed one night, and woke up to the pleasant surprise of a Giorgio Moroder track in his inbox. Matt: “I woke up one morning to about five emails that went from, ‘Hey, this might be happening,’ to ‘Just waiting for confirmation from Sony’, then a couple of hours later one that said, ‘Yeah, we got it’ with the first track sent through…”

Matt’s been in his new Northward Acoustics-designed studio for over a year now, and is seeing results on the bottom line, right where his dance and pop clients need the most attention. He said, it’s not just about adding weight and punch to the bass, but doing it in the right places.

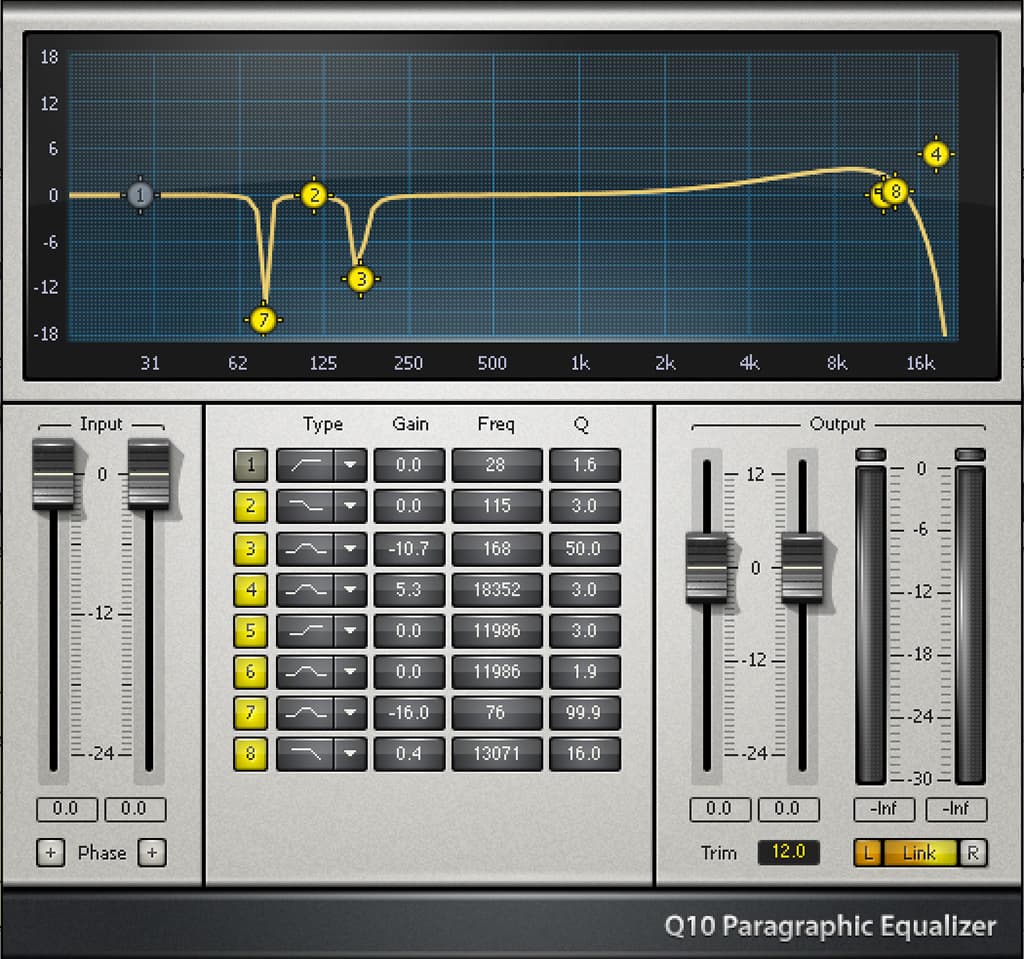

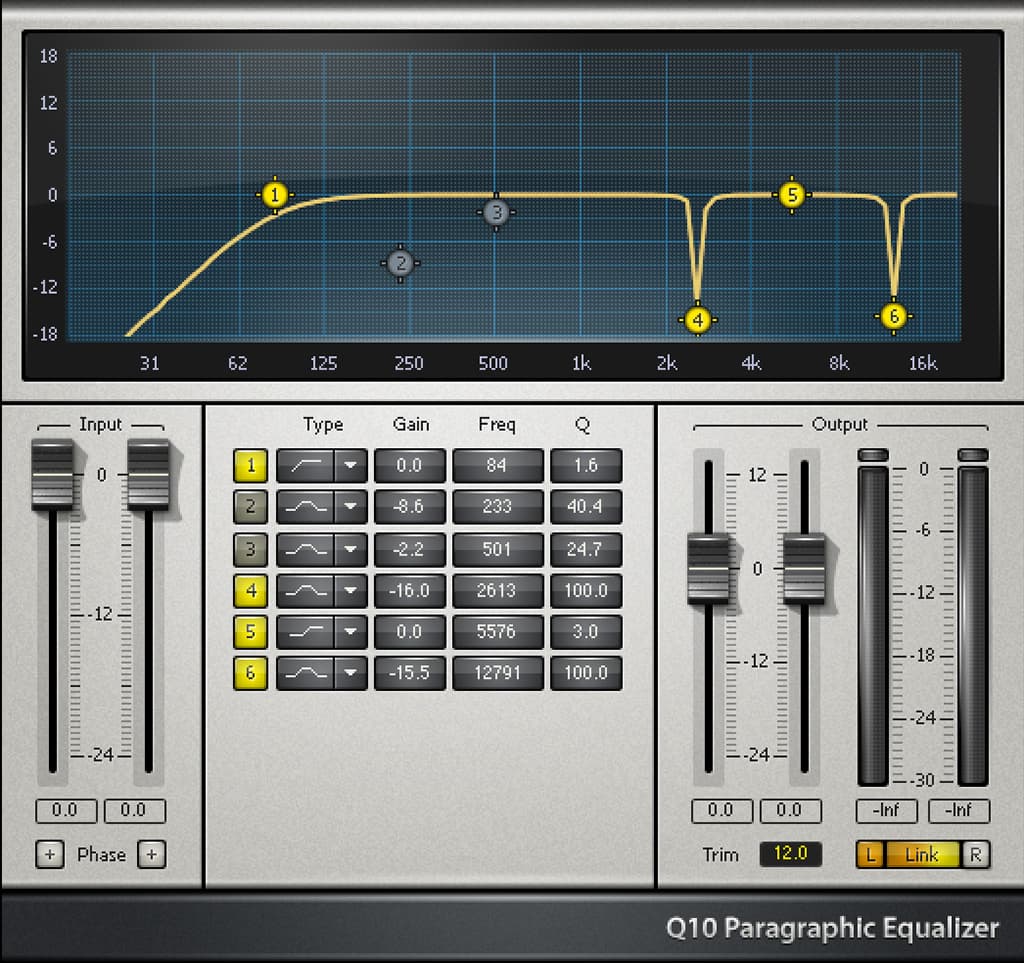

Matt: “It’s my job to try and bring the bottom end out where it sounds best, and tailor it so it’s tidy, and tighter and fuller in the right areas. A lot of the cuts I do are digital. A good EQ for that is DMG Audio’s Equilibrium. You can get exactly the right frequency, run it in MS or stereo mode, change impulse, and alter each band to different EQ models, like an API for the bottom end. Most importantly, it cuts really tightly and clearly, without being harsh. It’s the be-all-and-end-all digital EQ for me.

“I usually rely on my analogue gear for enhancing a track and making it sound fuller. The active Neumann EQs work really well on dance material. And my modified Buzz Audio REQ 2.2, with its active low band, is very transparent on any genre of music, but can also add low frequency saturation that can sound good on club tracks.

“I generally don’t compress much. Being a drummer, I’m conscious of how compression can flatten out drums and sink them into the mix too much. I work to keep it more open, punchy and tighter in terms of transients — less compression, longer attacks, shorter releases — which the API 2500 is good for. Then massaging it afterwards with something a little slower like the Thermionic Culture Phoenix, which adds some musical depth and vibe.”

DYNAMIC DANCE

Levels and dynamic range are a hot topic these days, so how does Matt deal with this gradual push upwards? “I basically leave that decision to the client. They can select one of four options on the job card: leave the dynamics true to the mix; slightly louder but keep most of the dynamics true to the mix; loud as music in a similar genre; or competing with the loudest music in the same genre. Then I also get clients to submit a reference if they’d like something to compare to. Most of the time, unless otherwise stated by the client, I won’t go any more than -8.5dB RMS in the chorus.

“Mitch really likes the tracks to come to life a bit more than what he’s got in the mix, but pushing in the same direction the mix is going. Getting choruses to jump out a bit more, and keeping the transient detail in the drums. I’ve got a few techniques I use to help with that. Some of it’s just macro-dynamics; automating between verses and choruses so you’ve got that dynamic lift. It’s even more important to preserve that during the mastering stage when you’re compressing and getting levels up.”

These simple automation techniques came in handy when he had to remaster Manny’s original Deja Vu mix for the album, which came in a lot hotter than Mitch’s. It was already hitting a high RMS value in the chorus before Matt had touched a knob. So he brought the level down about 5dB, and started finessing the macro-dynamics to try and bring a bit of variation back into the track. He did ask for a more dynamic version to work with, and got another copy, but with only another half dB off, it still required a fair amount of the same work.

On Right Here, Right Now Matt also automated the lead up to the chorus and EQ’d the midrange frequencies differently to the rest of the track to smooth out the vocals. “Because there’s a lot of layering going on and Kylie’s voice can get a bit full-on in those areas.”

ALL STARS FOR LINEUP

Even though Smidi had to fight for McCarthy, and McCarthy for Matt, it paid off. The result is an album that puts Moroder back on the map — 74 is the New 24 reads one of the song titles — without falling into any EDM dynamic traps. Smidi, for one, is sold on the lineup: “It’s really important to use the same team for an album, especially with tracks coming from different producers. The sonics were all over the map and those guys really helped bring it back to centre. I’ve got a new project, and it’s going to be Mitch, Matthew and I.”

RESPONSES