David Briggs: The Lonesome Loser?

He’s turned his hand to more aspects of music production than just about any other Australian from songwriting and live performance right through to mastering but is he really a ‘lonesome loser’?

David Briggs and I have been talking audio for about 20 years now, with gaps in the conversation here and there admittedly. To me David has always been the guy with the straight answer… along with the loudest and most contagious laugh in the history of audio. Whether the topic is songwriting, production, the science of recording, the benefits of the latest plug-ins – “I have them all” – mastering levels, down-sampling errors or bugs in DAW upgrades, ‘Briggsy’ always seems to have an educated response based on first-hand experience (and reams of documents to back it up where applicable). Well-known for engineering all day and reading and studying all night, Briggsy is one of the most gregarious, knowledgeable, scientific and opinionated men in the audio business. “I’m just a big kid with an enquiring mind,” he says of himself. “If it’s got buttons and lights on it I’m instantly attracted to it, and if I can pull it apart, even better.” If you want to know the facts about something, Briggsy is most often the man to ask. His knowledge base is wider than a Bob Clearmountain mix, and even more detailed.

Briggsy – as I’ll call him in this article from now on – is probably best known for his career as the lead guitarist of The Little River Band, for which he was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 2004, along with the rest of the band. He enjoyed a No.1 worldwide hit with LRB with his song Lonesome Loser in 1979 (which saw him collect an ‘Advance Australia Award’ for Outstanding Contribution in Music in the same year). He produced the seminal Boys Light Up album for Australian Crawl soon after, which went multi-platinum in Australia and made the members of the band household names. In the years since, he’s mixed and/or mastered more albums than just about anyone else in the country. Briggy’s walls are literally covered with framed gold and platinum-selling albums, and I’d wager there must be others gathering dust in a back room somewhere. But that’s not all he collects. There’s also Briggsy’s fabled guitar and amp collection, which will have you choking on your tea if it’s described to you mid-sip. Old Gibsons, Fenders, Martins, Voxes, Marshalls and Mesa Boogies abound at the Production Workshop – David’s studio of 30-odd years – the result of years touring in the US with The Little River Band. Briggsy still collects guitars, although strictly speaking the most recent purchase was a mandolin: “a 1918 Gibson that I just bought from a guy in Kentucky called James Brown.”

Then there’s the mic collection… did anyone say Neumann U47? Briggsy has three of this model alone, along with several pairs of KM84s, 83, 85 and 86is, 87s, 67s, KM74 and KM56 peanut valve Neumanns, a TLM170 and a host of AKGs. When they’re all out on display it looks like a Germanic invasion force. “While everyone else was still looking for old Fenders I was busy looking for valve Neumanns,” he remarks.

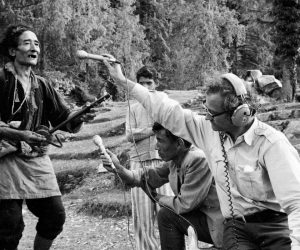

What’s fascinating about Briggsy is that while he’s spent a small fortune on audio equipment over the years, he’s basically never sold any of it. It all resides in the Production Workshop; some of it fired up on a daily basis, other pieces falling into disrepair. Take for instance his rare Lyric two-inch, 24-track tape machine that sits unused in the machine room. And when I say unused, I really mean unusable. I made the mistake last year during a late evening drop-in (no pun intended) of touching the machine’s pinch roller rubber as Briggsy and I talked idly through the machine room door about the usefulness of two-inch machines. As I causally motioned to spin the roller guides – as one does when one peruses tape machines – the rubber crumbled under my hand like a Ringwraith’s sword (see pic). This was one tape machine that hadn’t seen much work lately – maybe since I’ve known Briggsy in fact. But would he ever consider selling it? “Andy, I wouldn’t dare put someone through the pain of restoring it.”

Interviewing David Briggs for AudioTechnology was an odd experience for me, mainly because I knew covering all his bases would be impossible. When you don’t know someone very well you’re less aware of the topics you might overlook in the course of a discussion. With David, however, I was acutely aware that we could roll the Dictaphone for a week and still miss out on a small mountain of anecdotes.

For no particular reason I began our discussion by asking him about his recollections of working with George Martin on the Little River Band’s Time Exposure album at Montserrat in the West Indies, for which Geoff Emerick was the engineer and, coincidentally, Mike Stavrou was the tape operator.

David Briggs: I remember one night when we were recording with George I naively said to him, “Hey George, where are we mixing this record?” And he turned to me sternly and said, “We’re not mixing this record anywhere… I’m mixing this record!” [Go to AT’s website to read the fascinating letter George Martin subsequently sent to Glenn Wheatley, the band’s manager, in reference to the final mixes and track order of the album back in 1981: www.audiotechnology.com.au] That’s the kind of guy he was – succinct and to the point. George had great musical knowledge, was a good people manager and a very capable arranger. He also had a remarkably fair ear for a good commercial song – as we all know!

He was kind of like the headmaster of the group for that album. He’d be like; “Okay chaps, what are we doing now?” I remember George saying to me at one point that he thought the LRB situation was an extraordinary one because, as he put it, “Any one of you guys could produce this record,” which was a nice compliment.

If you’ve got a great bunch of players performing a great song, the damn thing nearly mixes itself...

THE PRODUCTION WORKSHOP

Andy Stewart: If we can spool the tape back to zero, as it were, for the benefit of AT readers, I’d like to ask you how you came to start the Production Workshop and who your competitors were in Melbourne back in those days?

DB: I started this joint over 30 years ago now, in 1979 believe it or not, with an analogue tape machine that I’d bought from AAV, my AKG BX20 spring reverb and a Soundcraft 16-into-8 desk. There were only about four or five other studios in the whole town at that stage: Alan Eaton’s, AAV, TCS Studio (Channel 9) in Richmond, Platinum, and Richmond Recorders… although Richmond went belly up soon after I think. There weren’t any boutique studios, only the main players in town.

It’s hard to conceive of now, but back then there was virtually no gear available for someone contemplating a modest home studio – not stuff that didn’t cost a fortune anyway. It was only really when ADATs came out that everything suddenly changed. Studios were affected badly at that point because suddenly people could record at home onto a digital eight-track recorder – or if they were mad (and wealthy) enough, two or three of them! They weren’t the best machine ever made, of course – Joe Camilleri used to describe rewinding and fast-forwarding several ADATs sync’d together as “the huskies” – such was their unruly behaviour! Even still, it was the beginning of the end worldwide for countless studios overburdened with rental payments, staff payments and equipment repayments and leases.

AS: What prompted the move from LRB guitar player to console operator and knob twiddler?

DB: When I started here I thought, “I’m a muso, I know what good recordings sound like. This shouldn’t be too hard.” I still remember the first time I put a microphone in a kick drum – I went back into the control room to listen to it; pushed the fader up and thought, “What do you do with that!?” It sounded like crap – ‘boing, boing’ – and then after a while I realised you could knock out 300Hz, add a bit of 2.5kHz and from there I guess I just started on my journey of learning how to engineer.

But just because I was a musician didn’t necessarily mean I could move over to the other side of the glass. That’s one of the issues I see – and I’d include myself in this – we all spend so much time reading the manual of whatever program it is we’re running that we often forget about being creative for the next six months because we’re trying to figure out how to make it go.

AS: Speak for yourself! You may find that you’re in fact the only person that reads the manual!

DB: Really? (Short pause…) But you know, I think people have forgotten how many benefits there are in simply having an engineer there to act as a buffer; someone who can twiddle the knobs, do all the left-brain stuff and free up the band to concentrate on their music. I don’t think it’s necessarily healthy for musicians to be tangled up in the recording process while they’re trying to perform at the same time. Going to a studio where an engineer can hit the record and stop buttons for you, and go, “Great, one more time,” or, “That’s good,” really helps people creatively.

Years ago the emphasis was on playing instruments well, not playing a take and then reaching over to the space bar to hit stop. You didn’t have two or three days to get something right either. You had 20 minutes. There were real beads of sweat and tension, and a collective pressure to perform a good take.

AS: Did that pressure help improve takes do you think?

DB: It did, for sure. Although, in my experience of recording albums with the Little River Band, I must admit we were usually in the luxurious position of being able to book a studio, or even two studios, for three months at a time. So I’m probably not the best person to ask that question. We were mostly developing songs in the studio, sometimes by ourselves, sometimes with a producer. I remember when we worked with John Boylan on Diamantina Cocktail, which included the song, Help Is On Its Way, John made me focus extensively on perfecting the guitar parts. There wasn’t pressure in the ‘we’ve gotta get this song done because we’re running out of time’ sense, but the pressure to refine and improve the parts we were recording onto our precious track of analogue tape certainly was.

If I look back to, say, producing the Aussie Crawl Boys Light Up album, that was done over a three-week period: one week of band tracking, one week of overdubbing, and a week of mixing. That’s all the budget we had. The problem was always that the further down the timeline of the recording process you went, the more rushed and lax you’d become. As I’m sure you’ve heard it said in the studio: “We can’t afford to keep doing this – we’ve only got two days left before we start mixing…” The key to that album was pre-production: I rehearsed the band for a long period of time before we hit the studio, so I had a fair idea of what to expect from them.

AS: That’s one of the great advantages of recording at home of course. There aren’t the same time constraints.

DB: Sure, but half the time there isn’t a decent acoustic environment either, let alone a range of microphones or an experienced engineer at the ready. I get lots of records to master that really could have benefitted from a good engineer recording it and a good producer going, “Hey, listen guys, one more time… that vocal’s flatter than a shit carter’s hat!”

But it’s not all like that of course. I master some fantastic work in here that’s been done by musicians working at home or in studios who have really got it together and learnt their craft as producers, engineers and performers.

Something I’m sure we both agree on is that if you’ve got a great bunch of players performing a great song, the damn thing nearly mixes itself because you don’t have to sift through 95 different ordinary takes. Prior to the emergence of digital non-linear multitracks we didn’t have to wade through all the useless crap while we were mixing because we couldn’t record it in the first place – the analogue medium simply couldn’t accommodate it. Then we tied two tape machines together and, oh my god, 48 tracks… more stuff we’ve gotta sort out and fit down that mix bus. When you think about it now, 24 tracks seems like nothing. Without naming names, I know people these days who’ll record 80 tracks… of vocals alone! Everything else is then quadruple-tracked, tripled and then doubled and, holey moley, did we really need to do that?

What are you supposed to do with all that stuff when it comes time to mix? That’s one of the things I learnt in my time with the Little River Band – the art of developing parts. It’s critical in album production to focus on the parts – keep the good bits in there and repeat them. That’s one of the great things I learned from John Boylan and the rest of LRB. We were always onto each other about developing our parts so that there was the essence of a song there. The litmus test was that if you pulled down a fader you could immediately say “hang on, there’s something missing now, put it back.”

GOOD IDEAS

AS: What do you need to produce a good record these days would you say?

DB: I’m at the stage where I don’t really need a lot of gear, only good ideas to work with. It’s all about people with good ideas, in my book. After that it’s mostly about sitting back and trying to keep your hands off it. That’s one of the things I’ve learnt about producing over the years. It’s not about saying to the artist: “Look, don’t panic, I’ve got all the ideas, you don’t need to have any.” That might work very occasionally for some people but it mostly doesn’t. By all means help the artist: be the big brother, the psychologist, the bottom wiper, at times the good guy, at times the bad guy, depending on what the situation is. But it’s imperative to remember that different situations require different tact, and knowing when to keep your hands off the music is probably the most important lesson a producer can learn.

There will always be those situations at the start of a day in the studio, for example, where you’re working with a new band – not necessarily as the ‘producer’ – and figuring a particular approach the band has adopted is never going to work. You (luckily) don’t say anything at the time, despite your misgivings. You’re trying to resist being Mr Producer guy who feels he has to prove to these younger guys that he has all the answers. Thankfully you don’t put the kibosh on the approach because by the end of the day it’s worked! And you go, “Oh, I really learned something out of that.” I’ve been in enough of those situations to know that trying to assert your musical will all the time is folly. And besides, I hate to be the guy with the velvet sledgehammer going, “No, no, that’s not gonna work!” and knocking things on the head.

There are so many hats you can wear in this process: from an operator, through to producer, performer, and surrogate songwriter. I’ve worn them all over the years because I like doing it and if I didn’t do this I’d probably be doing something horrible. I’m a band player when it’s all said and done. I’ve been playing in bands for well in excess of 30 years and I like that process… although going on the road for long periods of time – that, I’m not so keen on!

AS: Is that what inspired you to take up producing bands then, rather than playing in them?

DB: During my tenure with LRB I was working with other people in the studio a lot, and I really enjoyed working on other people’s tunes and helping them through the creative process. And I figured I’d spent so much time in the studio – for better or worse – that I’d like to learn more about it. That’s why I set up my own place here; so I could sit and learn how to engineer.

I wanted to know more about things like: ‘Why do we always use this compressor on the vocal?’ ‘What does that other one sound like instead?’. When I experimented with stuff here I could discover sounds for myself and go: ‘Oh, now I know why we don’t use that!’

It’s critical in album production to focus on the parts – keep the good bits in there and repeat them

MASTERING

AS: You’ve also been a mastering engineer since around 1990. When you’re wearing this hat, as opposed to all the others, do you approach things any more scientifically?

DB: Not necessarily, no. In mastering, if something already sounds good then I know I shouldn’t be doing too much to it. That applies to all aspects of this caper. Conversely, if it doesn’t sound good I’ve got a few techniques that I’ll apply to help it along, but it will never sound as good as if it had been half decent to start with. And sure there are some technical processes involved but the decisions I make aren’t just ‘scientific’, not at all. Mastering is primarily about understanding the genre of music you’re working with. A good mastering engineer requires a good understanding of music styles and how each one’s dynamics and tonality works. If it’s reggae it’s gonna be big on the bottom end; if it’s classical music it’s not going to be compressed and so forth.

The mastering engineer has to be respectful of the artist, respectful of the music, respectful of the producer and the engineer, and like a producer, the mastering engineer has to try and avoid sticking his or her fingers all over it. If the artist comes to you and says, “we’re really not happy about the way our recording sounds; is there something you can do to get it a bit closer to how we want it?” then sure, I’ll put my fingers all over it.

There are technical decisions that have to be made too of course: Do I process this as a stereo audio file? How do I deal with its EQ and dynamics? Do I use a mid-side process? Do I worry about the sibilance of the vocalist seeing as how the producer and the engineer haven’t considered it?

Then there are the sub-categories of all those technical decisions: If I’m going to put a de-esser on a song, do I work that into a mid-side matrix? If so, where in the chain will I put it and which de-esser will I use? There’s a whole range of those kinds of questions I have to make decisions about pretty quickly once I hear the music and go: “Righto, I can hear that we’re sibilant, I can hear that it’s dull, I can hear that it’s not very wide etc.” Otherwise you can end up spending as much time mastering as you did mixing.

AS: I know you use ProTools as your mastering DAW. So what program are you using to make the final Red Book CD?

DB: I use Waveburner. There’s a variety of packages around but Waveburner has been pretty good to me. Occasionally I use TC Spark to write DDP files – as I believe you can in the newest version of Waveburner – but I don’t have that yet.

GOOD MIXING/MASTERING

AS: As a mastering engineer, what are you hoping to hear in a good mix?

DB: A good instrumental balance; a good bottom end; taking note of the fact that the vocalist is not exceedingly sibilant and that the overall tonal balance of the mix is not too dull. It’s important to develop an intelligent left/right placement, left/right balance, good depth of field, and not over-use effects such that they do weird things when you apply compression or limiting.

AS: Flipping the question around, as a mix engineer what are you looking for out of the mastering process?

DB: Well, fundamentally it’s about having a well-balanced piece of program to start with. As a mix engineer you want the mastering engineer to understand the genre of the music you’re presenting to them, and respond appropriately. Obviously there are some things best left dynamic and other things that require fairly heavy limiting. For instance, metal bands generally don’t want something that’s too dynamic. They want it to play loud in their CD carousel alongside Pantera and whatever else – they’ll be playing it against the most processed records on the planet and it’s gotta sit in there. Really it’s a case of helping people to feel comfortable about where music fits into the grand CD carousel of life, and how we get it to that stage. That’s an education process as much as anything, whether you’re the mastering guy, the mix engineer, the engineer or the producer.

HI-RES PROCESSING

AS: Before we wrap this up, can we talk briefly about the issues you have with down-sampling final CD masters, and the ‘overs’ potentially embedded in them? To start the conversation off, are you mastering at high resolutions or up-sampling projects at all?

DB: That’s an interesting question. The whole debate about high resolution CD processing or ProTools processing or DAW processing, is a moot point to me – as I’ve expressed to you before – because I’m never happy about the down-sampling. I see CDs clipping all the time, especially if they’ve been processed at elevated sample rates and then down-sampled during the latter stages of the process. It’s especially prevalent when uneven multiples of the destination sample rate are involved: ie, from say 96k to 44.1k.

I’ve played around with elevated sample rate mastering but generally if I do something at 24-bit/96k and then down-sample, often it feels dull when we get back to 16-bit.

AS: But if you pull files in at 44.1k, are you not simply transferring that conversion point to a different part of the chain?

DB: Yeah, but it’s unavoidable.

AS: So why is it better to do it early do you think?

DB: Well, because the end result is more predictable tonally, and you don’t get these clips occurring… what’s generally known as the ‘Gibbs phenomenon’. If you process your masters at high sample rates and then, as the last stage of the mastering process, down-sample to 44.1k, you can generate ‘overs’ that simply didn’t exist prior to down-sampling taking place, as a result of the unresolveable mathematics. The maths involved in down-sampling from 88.2k to 44.1k is an elegant equation, but 96k to 44.1k is not. Hence the possibility of clipping during the course of down-sampling, especially after serious limiting and equalisation at elevated sample rates has taken place.

AS: Are these ‘overs’ audible to you or are they only apparent on the analysers?

DB: They’re there.

AS: So does it matter?

DB: Well, let me put it this way: “Don’t panic, I’m just distorting your audio!” I don’t feel comfortable about that.

AS: Presumably if you’re clipping the masters you’re driving them into a land of unpredictability. Is that what you see the main problem being?

DB: Thomas Lund from TC Electronic delivered an AES paper on this called ‘Stop Counting Samples’, where he went through and listed (by brand and model) a whole range of CD players and where they start to clip in the headroom stakes. And some of them clip a whole lot earlier than others! I don’t feel comfortable about knowingly being aware of distortion or clipping the audio. I don’t buy the concept of soft saturation – I don’t like it at all. Mr Lund has also delivered papers documenting the Gibbs Phenomenon, which are well worth reading.

I’ve got a whole range of CDs in my ProTools rig that I’ve sonically reviewed, from AC/DC through to Coldplay, and you can see the ones that clip at intermittent points. And it’s these intermittent points that are crucial to this discussion. I’m not referring to things like AC/DC’s Black Ice record, where the first two tracks basically clip on every kick and snare sample. I’m talking about the specific issue of audio that’s been mixed at an elevated sample rate, mastered at that elevated sample rate and then down-sampled as part of the final process. That’s where this random clipping occurs.

Now, while I don’t hear that clipping, I can see that it’s clipping on my analyser – a device that measures down to single sample resolution – so there’s no doubt that it’s clipping, that’s not the argument.

AS: They’re not musically dynamic clips… just purely random as a result of the down-sampling mathematics?

DB: Yeah, it’s a random thing, not a predictable thing. Suffice it to say I try not to clip the audio.

(NOT) ALL ABOUT THE LYRIC

AS: When did you last use the Lyric tape machine, by the way?

DB: The big cassette player? Years ago now.

AS: The last time I touched it, it sort of disintegrated in my hand like something out of a sci-fi movie.

DB: That’s right. The rubber has turned to Flubber!

AS: Why did you stop using it?

DB: The thing about an analogue tape recorder is that if you listen off the repro head when you’re tracking, then flick back to the line input and have a listen to what’s going into it, you quickly realise that what’s coming off the tape recorder is a pretty fuzzy representation of things. That bothers me. I’m into progress, not regress! But vintage guitars? That’s another story…

RESPONSES