Courtney Barnett’s Really Feelin’ It

Courtney Barnett is big time and runs her own label. She could have recorded her new album anywhere, with anyone… but why go to Electric Lady when you can stay home?

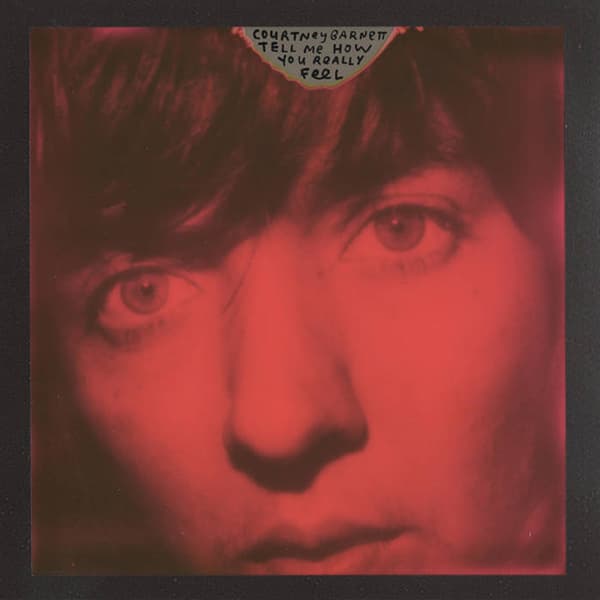

Artist: Courtney Barnett

Album: Tell Me How You Really Feel

Courtney Barnett is a paradox; fame and entrepreneurialism dressed down in a flannel and beanie.

She’s an American TV late show star and indie music entrepreneur with her own record label whose lyrics chronicle life with a tenor of self doubt and anxiety. The lead track off her new album is called Hopefulessness, a slow build jam that tails off into the vexatious sound of Barnett’s own kettle whistling away on the gas stove. It’s the sound of her anxiety captured on an iPhone. “When I’m at the other end of the house and hear it going but can’t get there, it really stresses me out.”

If you could visually reconstruct the melancholy haze of Barnett’s lyrics on songs like Depreston, you’d end up with the strip of shops her Milk! label headquarters is nestled into. The red-painted brick building still has the markings of an ex-industrial solvents outlet, and its flanked by mostly decrepit or defunct businesses for which time has moved on.

Inside, the front is stacked floor to ceiling with merch. Wall-to-wall t-shirts surround a central island bench. It feels crafty and DIY, like the cutting table at your local Spotlight. I meet Barnett out the back, where the band/loft space is separated from the front by a giant curtain. It’s Barnett’s happy place — guitars, Fender amps, a drum kit, PA, and the perfect place to procrastinate. When she was meant to be writing lyrics for her latest album, Tell Me How You Really Feel, she would distract herself by hanging fairy lights. “I spent three hours nearly falling off ladders trying to hang fairy lights!” she said. “I had this manic idea that I needed to have fairy lights every where to have a vibe. Burke [Reid, producer] was like, ‘Stop with the fairy lights and write your lyrics!’”

MILKING IT

Owning and running a record label wasn’t part of a master plan. It just kind of happened after Barnett finished recording her first EP at a friend’s place. “It came to the point of putting it out and I didn’t really have any idea of where to send it or what you’re supposed to do,” she said. “It seemed just as easy to start my own online store and sell it, which was essentially how the label started. I used social media and tried to shop it around to people, then it grew a bit and I put friend’s albums on the store.”

The independence has worked well for Barnett, who would “recommend it, though people don’t anticipate how much work it is. It’s a weird industry of working around the clock, and social media is part of your work, but it’s great. We can create our own projects, compilations and tours. We did a tour with all the bands around the east coast of Australia because we decided it would be fun.”

These days she and partner, Jen Cloher, run the label. Barnett says Cloher is now the label manager, “and does most of the daily stuff. I do a bit more hands-on stuff, design the merch, and boring back end website stuff. We also have labels based in London and New York, and Milk! Records goes through Remote Control in Melbourne, so there’s lots of people working on it. We’re not doing everything, that’d never work.”

Despite Barnett being the boss of her own label, she prefers to keep things low key. When it came to choosing a studio to record Tell Me How You Really Feel in, Barnett kept to the status quo of her last album: same city, Melbourne; same engineer and producer, Burke Reid; and same band — Dave Mudie on drums, Bones Sloane on bass and co-producer Dan Luscombe on lead guitar. The only thing that changed was moving five k’s down the road from Head Gap to Sound Park Studios.

“I’m a bit indecisive so I kept leaving it till later and later,” she said. “I’d done random sessions in studios around the world: New York, Wales and London. I thought about going back, but I find it a weird business to pick a producer, engineer or studio you don’t know or have never been to and just lock it in. You have no idea from a chat how it’s going to work. My brain can’t wrap around that. They could be a total arsehole or really condescending.”

She’s not against change or experimentation, but there was an element of being paralysed by choice. “Once I realised that I wasn’t just restrained to Melbourne, it was almost too much,” she explained. “Do I want to go to a cabin in the woods and make an album there? Or do you go to Electric Lady in the middle of New York? I came back to the fact I wanted to do it near home and I really respect those guys and their musical choices. So let’s just do that again and have fun. I like Sound Park, I found it to be a bit homely and not too sterile; there’s knick-knacks everywhere.”

Before Sound Park was even on the cards, Barnett had a completely different approach in mind. She and Reid spent time at The Grove Studios, where Reid is based, with Barnett playing all the instruments. “I went with a loose intention to make an album, but it ended up being lots of demos and ideas,” she explained. “I was playing all the instruments, but I was still working on and struggling to finish the songs. It was a fun process, and very challenging playing all the instruments and tracking it to clicks, bit by bit. Normally we just do it live, without too much fussing around.”

“It was really good for Courtney to get her headspace back into the studio and working on the writing stage. Taking some of the pressure off,” said Reid, who helped jury-rig sounds and set up drum machines to help get the groove. “Drum machines are a good way of getting a song together quickly, because you can try different rhythms really fast, and different sounds, put them through amps and distort them and get inspired.”

Barnett liked the results, but not enough to turn it into an album. “That was the headspace I was in at that time. I liked the idea of basic, slightly DIY-sounding stuff, but then I didn’t want it to sound too s**t!” It took another seven months before she showed the band, and headed in to Sound Park.

I find it a weird business to pick a producer, engineer or studio you don’t know and just lock it in. They could be a total arsehole or really condescending

PARKING IN ONE SPOT

Reid tried to count the number of studios he’s worked in. Around 20 was as solid a number as he could muster; more than a few. When I talk to him, he’d just made it to the UK for pre-production with Flyte before heading into Chale Abbey Studios on the Isle of Wight. “It’s a beautiful converted barn, almost church-like inside.”

Reid had never worked at Sound Park before, but he’s not too worried about where he records, as long as most of the gear works and the vibe is good. “A happy band leads to a happy album,” he said. “I can usually find ways around problems on my end.”

He was fortunate to have spent a week doing pre-production in the rehearsal room at Sound Park, which meant he could poke his head in and try stuff out. When he walks in cold, Burke says a quick squiz is usually enough to take in the acoustic limitations, then his first stop is the microphone cabinet to see what he’s playing with, and what works. “If it’s a brand new studio, I might try some interesting outboard, but I usually do lots on the console and only use a bit of outboard gear. I don’t like to get too complicated.” Sound Park has an MCI board now, which was in great nick, and Burke was more than happy with the microphone collection and variety of instruments on hand. He also loved the DIY acoustic treatment: “It’s not super schmick, which is good, because it settles everyone in pretty fast. It takes the pressure off — you’re not looking at the clock so much.”

Reid said sessions with Barnett go relatively quickly. They spent 10 days recording Tell Me How You Really Feel. “She’s super fun to work with. Nice, easy going, and when the decision needs to be made, she makes it,” said Reid. “Sometimes she knows exactly what she wants, other times you offer a few avenues to go down, then she knows exactly what she’s after.”

MO-JANGLES

Barnett’s go-to tone is a bit of distortion and chorus through a Fender Deluxe amp. “In radio situations people are always telling me to dial the treble down, but I like it slightly abrasive and the real jangle that comes with it. I used a lot of chorus and on the last lot of touring as a three-piece, which would make it all sound a bit bigger! But it gets a bit old after a while.”

To help expand the palette of tones on the record, Reid and Luscombe would put their heads together and devise a pedal and amp combination for each part. “It was always about conveying the uniqueness Courtney has in her lyrics on the music side as well,” explained Reid. “Dan’s a great musician with awesome taste. We talk a lot about the colour and vibe. We all know that language pretty well, so it’s about having access to the finer ingredients. Dan’s great at pulling out something left of centre, which is usually the one that makes the cut.”

“I’ve just always respected his taste more than anything,” concurred Barnett. “He has a really encyclopaedic knowledge of music. If I’m second-guessing myself, I’ll ask him. If he likes it, it’s okay! I’m so vulnerable and sit there thinking everything’s terrible and I’m making a terrible idea. It’s nice having that reassuring person.”

For guitars, there would have been any of a number of amps, pedals or chains of pedals. For Nameless Faceless Luscombe capoed Barnett’s guitar and pulled two strings off so it sounded ukelele-ish. Other times, he’d pluck piano strings, or Barnett would use a bow to create the foreboding drone at the beginning of the album. “For Crippling Self Doubt & a General Lack of Self Confidence, he found something called a VHS Counter. I don’t think it was a guitar pedal. It made it alien and underwater-sounding.”

“One consistent thing was the amps were played extremely loud,” said Reid. “Lots of the distortion was from hot hot amps, and the microphones overloading a little bit.” Reid has a particular affection for AKG C451 pencil condensers on guitar amps, but the pads aren’t often enough to cope with the barrage of level. “I’m not the biggest fan of using pads on consoles. I prefer it on the microphone,” he said. “Dan had a pair of Oktava pencil mics that come with these screw on pads. They’re great because you can screw on multiple pads and get a 30dB pad. Then I just move it around. There’s a bit of distance, maybe a foot or so from the actual amp. Even then, I’m not really able to go past one click on the preamp. I like condenser mics and ribbons on amps, sometimes 57s. Maybe one mic will not be handling it well, then I’ll have another mic that’s really padded to blend in if I need a cleaner version with dynamics.”

CORNERING THE DRUMMER

Reid wasn’t terribly interested in capturing any large ambience on drums at Sound Park. After trying a few spots and finding the bigger room a bit tricky, he eventually settled on pushing the drums into the corner of the medium-sized partition. “I tend to make my drummers struggle to get into their drum kits,” said Reid. “Dave was a good sport. It wasn’t about getting a bombastic room sound. Any room mics are only about four to five feet away from the kit, capturing really short room ambience.

“Drums are the thing that matter most in the room, so finding the right spot is important. When I know cymbals are going to get smashed a bit more, I’ll angle my overheads differently. I’ll also see how far I can move the cymbals away from the kit to get more space around the skins. Squishing drums up against the walls makes them resonate more, and putting padding up on those walls helps tame the cymbal reflections. You just twist and turn until it sounds good. Then record.”

Reid’s always looking for a place to stick a Shure SM7 dynamic crush mic. “Sometimes it’s in the middle of the kit nestled just above the kick drum, other times up high,” he said. “Dan has a U47 copy from Bees Knees, we were putting it up against the kick drum and it was blowing up the preamp in a really cool way, adding an almost electronic sub. Sound Park has some really cool Pultec-style EQs. They’re fun on an SM7, you just pump the lows and highs, then put it through a compressor.

Reid is very conscious of drums not eating up his entire image, preferring to keep them largely mono and push guitars out wide. “Keeping drums mainly mono helps the punch cut through,” he explained. “When you start layering a bunch of things top, it’s harder to get the centre through. The more space you have between hits keeps the centre feeling more aggressive.”

Instead of spreading his overheads, he’ll often look for ways to exaggerate movement. “I had Coles ribbons as overheads, but facing each other on either side like a pair of ears,” he said. “When you have them facing each other on the edges of the cymbals, they do weird phasing things across the stereo spectrum, which can give movement.

“I use Soundtoys’ Echoboy a lot, but not necessarily for delays. You can change it to ‘Time’, and I’ll play with it at about 12 or 13ms. Then there’s a Memory Man or Space Echo patch in the other menu that allows you to play with the modulation. There are two knobs you can move one click at a time and it screws with the space. Sometimes I’ll take a room mic, snare, or whatever, and double it, then put a stereo Echoboy on, and have it modulating. When you blend it with the original source, it can shift things in weird spots and keep it moving. I like spatial things that modulate so they’re not static. I used to not like hi-hat mics, but there’s always a song where you’ll need it. They’re also fun mics to destroy and bring up other parts of the kit. I might put a Panman on it, and have it moving back and forth in time slightly left and right. Sometimes either side of the centre, or over in the left speaker so it sounds like their hand is going up and down.”

FAIRY LIGHT GUIDES

Once Barnett finally had her lyrics sorted, she brought her two clumps of fairy lights and strung them up a Sound Park. “It became this joke, they were all around me,” she said. “It was ridiculous.” Other than that, she would prefer people clear out for her takes, the lyrics were new, constantly changing. “It’s incredibly vulnerable, so to have people in the control room would make me nervous.”

“Some of the vocals were live from the band takes,” explained Reid. “When we set up to do the tracking, we were trying to get a microphone that wasn’t super intrusive and daunting. We wanted something that wouldn’t pick up as much of the band if we decided to use it, and one she could get her face into. We used an Electro-Voice RE20 into a big red Giles Audio VMP-2B tube preamp and it sounded amazing. I threw it up for guides, but we really liked it and ended up using it for all the vocals. When we’d overdub stuff, we’d sometimes have her playing along on an unplugged guitar just to have that feeling of playing along with the band. That helps the delivery, because you’re concentrating on something else other than your vocals coming through the headphones.”

I’m so vulnerable and sit there thinking everything’s terrible and I’m making a terrible idea. It’s nice having that reassuring person

AUTOMATED FOOD FIGHT

Reid took the sessions back to the The Grove, where he mixes in the box using a load of parallel chains laden with saturation and distortion. “It can look a bit mad,” he said. “I have the intention of starting out organised, then it can look like a bit of a food fight. Sometimes I’ll have two or three parallels, and phasing can take away punch, other times it can add extreme highs and lows. If you get that balance right with your close mics, you might change the tone of things, but it can be interesting and add a weird spatial element to it.”

Because he moves around between different studios, Reid has tried to keep his list of plug-ins short. He’s also not on the UAD train, despite having used them and finding them tantalising. “I’m trying to use plug-ins I know I can put onto any computer. I have the installers with me and I know they work. That way if I’m travelling or working at another studio, I’m not relying on carrying around a UAD system.

“I used to fall into the trap of ‘needing’ this or that, but I lined up a bunch of different compressors and played around with them. There are one or two that sound a bit different, but you can get in the ballpark with the ones I have. Having one or two plug-in compressors that I know well is fine. It’s like outboard gear. Just pretend that each plug-in costs $3000. Figure it out, and use it in the situations you wish you had something else, but it’s all you’ve got.

“I really like the Soundtoys bundle, and the Eventide plug-ins, which can be similar in some aspects. I use Kush Audio and its offshoot, Sly-Fi, a lot. Sly-Fi has an API-style EQ, the Axis, which has a distortion knob on it that sounds really great. Sometimes I just use that knob. Some of them are simply the first plug-ins I used and know. I’ve been bringing back the PSP Vintage Warmer a lot these days. I use the Valhalla a lot for reverb, it’s pretty flexible.”

While Reid is a sucker for nailing the drum and bass groove, he says automation is “one of the most important things in a mix, and one of the laziest to get around to. You can spend a lot of time with a kick drum, but in the mix it might not make as big a difference. You’re orchestrating the mix when you automate. You can make performances really come to life. I try to get sounds and balances happening fast, then start automating, turning effects on and off, doing weird pans, pushing the master fader up in spots, pushing drum fills.”

Reid prefers to do the bulk of his automation on trim plug-ins at the end of his plug-in chains. “That way I can copy that trim plug-in to different instruments, if I want them to all do the same automation,” he explained. “The trim plug-in starts at 0dB, whereas your drum bus might be at a particular plus or minus level. If I want it to happen on my bass too, I can’t copy the fader automation, because it might be at a different initial setting. However, I can just copy that trim plug-in and it’ll ride the bass the exact same way from its initial level.

“I can also bypass them easily, which seems a lot faster than flipping between the channel automation. It also means I can do broad level changes on the faders. For instance, if I’ve gone through and automated volumes on a trim plug-in on my drum bus, I can still fade the drums out in a spot or do another last minute volume automation, over the top.”

RESPONSES