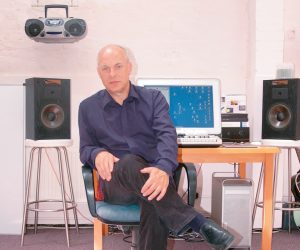

Brian Lucey: Mastering the Black Keys

Mastering engineer Brian Lucey isn’t concerned about loudness wars and high resolution files. He just wants to move air and the people that hear your mix.

Photos: Beth Herzhaft

Fortuitously, when he first took a call from ‘Dan, the producer out of Akron’ in 2008, Brian Lucey had just spent the previous couple of days mulling over the best way to answer the question mastering engineers always get asked: ‘How does your work compare with Sterling Sound, etc, etc?’

It’s a tough one. No one likes self-aggrandising, but if you’re not confident in your work, why would anyone else be either? So he gave his new answer, straight-up and honest: “Well my clients say the work is on par with those people,” started Lucey. “But obviously those are industry giants who’ve been around for decades. I will never have their history, and my name doesn’t have that kind of cachet.”

Dan got it, a real Ohio native-kind of guy; you aren’t anything special until you show it. He’d tried Sterling and the rest, and wasn’t blown away, so he started sending Lucey projects to master. The first was a record by a band called Hacienda, which racked up four stars in Rolling Stone. Lucey was excited about the positive exposure, that was a relatively big hit for a client at the time. But Dan was still just the ‘producer from Akron’ to this local Columbus, Ohio, mastering engineer.

The projects kept coming, and towards the end of an on-and-off three-week revision process for one, Lucey recalls Dan saying, ‘Well I go on tour tomorrow, so I’ll be in Phoenix, just send me the mixes whatever and we’ll talk.’ Lucey hung up the phone and thought, ‘Phoenix?!’

He explains: “In the United States of America, Phoenix is not a major market you’d think to tour, particularly a band from Akron, Ohio. From Akron, you go to Detroit, or to Chicago, New York or Philadelphia, or you go to Nashville, or Memphis, Columbus or Pittsburgh or Indianapolis. In a 500-mile radius, you can go tour a lot of places. Not 2000 miles to Phoenix!”

So Lucey did what anyone would do, he googled his name — ‘Dan Auerbach’ — the result was pages and pages of references to The Black Keys. Dan wasn’t just the producer from Akron, he was one half of The Black Keys.

This was pre-Brothers in ’08, though the band was already huge. But when Lucey mentioned it to Dan, he shrugged it off. After all, no one likes someone who toots their on horn.

From there the two Ohio natives kept working on material Dan was producing, like the Dr. John record, till one day Lucey got offered the new Black Keys record mixed by Tchad Blake. “I was actually having a really bad day with relationship problems,” recalled Lucey. “I’d gone to visit my parents and got this call asking if I could do the new album in three weeks. I was like, ‘yeah, I think I can probably fit that in.’”

That record ended up being Brothers, a massive hit. Lucey: “They were very successful before Brothers but I think it’s fair to say it took them up a whole new level. I was doing very well before Brothers, but I’d never done a really big record. So for both of us it was a really big record.

“It just happened,” said Lucey of the now long-term relationship. “We built trust over a couple of years of getting to know each other. I don’t know why he initially called. I never asked him.”

Since then, Lucey has gone on to master every subsequent Black Keys release, and releases for Arctic Monkeys, Beck, Sigur Ros, Ray LaMontagne, and The Shins, as well as Aussie hits like Chet Faker’s Built on Glass.

MASTER OF MEDITATION

The path into mastering was gradual for Lucey. He worked in New York City as a professional guitarist and singer through the ’80s and ’90s, but it wasn’t until he studied Robert Fripp’s Guitar Craft that he really started meditating on the vibrational aspect of music. It was a blessing and a curse, because the more he dwelt on the mysteries of tone, the less satisfied he became with his band’s recordings.

He had a $55,000 house to his name, so he took out a loan, and started making records at home. Eventually that led to producing, a 16-track, two-inch Ampex MM1200 and racks of outboard gear — he was getting all the tone he could eat.

Somewhere along the line he began mastering, and by 2000 it started taking over to the point of having to give up producing and being a musician.

“It didn’t take over in a way that was disappointing,” clarified Lucey. “It was as if it was what I was trying to do the whole time, I just didn’t know it. To me it was about vibe. And in mastering all I do is vibe.”

Lucey learnt by making plenty of mistakes, on his own time. There was no understudy role churning out ghost-written masters for bigger names. He developed his own approach, through trial and error, a lifetime of A/B’ing and plenty of experience. And the journey has really galvanised the 47-year old’s philosophies about his craft.

IT’S ALL ABOUT VIBE

If you had to sum up Lucey’s mastering philosophies, it would be about vibe. It’s a nebulous description we use when we can’t quite put the finger on something. It’s vague and loosely interpreted, but to Lucey, the definition couldn’t be any more clear cut. For him, vibe is about vibrationally connecting listeners with the artist. It’s the only means musicians have to get the world ‘on message’, and it’s his job to ensure it sticks.

“The goal is that someone hears the single, buys the record, and goes to see the tour,” says Lucey. “At least that’s how I see it. So a single has to vibrationally connect you with the artist. The album brings in the flow factor, and I don’t think that part is any different for me than any other mastering engineer. I think a difference is the vibrational/musical focus I have, as opposed to any specific technical thing.”

THE SIX STEPS

The trick, reckons Lucey, is to have positive compromise. “I forget who first phrased this concept, might have been Bob Olsen,” said Lucey. “Everywhere in the production process, there’s some harm introduced to the audio. The goal is to gain more than you lose at every step.

“This might make me sound crazy, but I believe all the potential music in the world exists somewhere in this place of silence. And the artist hears and draws something from that silence and gives it a voice. At first it’s kind of raw, it might be a hook or a verse line, but it has potential.

“Then the next step is arrangement; they take that inspiration and structure it in a way that connects with more people without losing the original inspirational intent. That original rawness is lost to some extent, but they’ve arranged it in a way where you or I might get what they mean.

“You go in the studio. Let’s say it’s the new U2 record and they want to record live because they can. The result is never as cool as being in the room, something was lost, but something was gained because now we have a recording.

“To me there are six steps: Inspiration, arrangement, performance in the recording studio, tracking engineer, mixing engineer, mastering engineer. If you have a positive compromise at each step, it can be an amazing record.”

THE LOSER STRATEGY

The other side of the coin is fear, and Lucey sees it all too often in mastering, when mastering engineers dictate the final balance of a mix and mix engineers start second-guessing themselves. Lucey: “People tell me their last mastering engineer did all these certain things so they’re going to mix for the mastering engineer. Wrong! You need a new mastering engineer. My job is to not f**k up anything you love, while at the same time improving on everything that you love.

“It’s very LA from the old days,” says Lucey about vocal up/vocal down mixes. He personally doesn’t see the point of mixers sending him any other mix than their best one. Wonder if a vocal is too low, or bass too high? His advice is to figure it out yourself and fix it. Listen to it on lots of speakers, get the producer’s partner in for a listen and see if they like it. “You’re the production team, and the original test market,” reminds Lucey. “You should be happy with one song, done one way.

“For example, when Dan and Tchad called with the Brothers mixes, they were very respectful to me, asking things like, ‘Do you want to hear it down a dB because we’ve used a limiter?’ It was a funny thought to me, ‘Let me get this straight. You, Tchad Blake, and you, Dan Auerbach, like Mix A. And you’re asking me — who’s never heard it, had no part in the process up to this moment, didn’t write any of these songs or build any of your careers — if I want to hear Mix A down a dB? No, I want to hear Mix A. I want to hear the mix that makes you two go, ‘that’s the f**king one!’’

“Now they insisted at the time and sent Mix A minus a dB, and you wouldn’t think it mattered, but it totally mattered. It took 10 seconds to say no. Because there’s something quite magical about that moment where a mix comes together.

“Whether you’re self-producing in your bedroom or you’ve got Danger Mouse producing your record — if you love your mix, that’s the one I want. If you start to play it safe out of fear, either making it louder or quieter, it doesn’t matter. The energy you’re bringing into it is fear. And you’re blowing the specialness of the sound you’ve all created. I want the special one, not the safe one.”

Whether you’re self-producing in your bedroom or you’ve got Danger Mouse producing your record — if you love your mix, that’s the mix I want

CHAIN OF TOOLS

Beyond vibe, positive compromise, and encouraging artists and mixers to stick to their guns, there is a technical aspect to what Lucey does which contributes to his success. Notably, three things he considers quite hard to do: volume without smashing it, low end without crapping it out, and harmonics that still sound clean and respectful to the source but are actually harmonically distorted.

“It’s a tricky cocktail because low end and volume tend to equal distortion,” said Lucey. “And I make no bones about it, I flirt with that line. I don’t compress much, if at all, and I can make some very loud records that still move air. It’s very important to me to move drivers. I like low end power and the intimacy that comes from it. For me, intimacy and connection with the widest audience is the goal. If we’re not moving drivers, we’re not hitting people in the chest, they’re not going to dance. It’s just going to sit there being flat, loud and annoying.”

The synergy of his signal chain is what Lucey credits as giving him the ability to flirt with that line. Lucey has AB tested the daylights out of his signal path to come to a place where the chain naturally enhances the sound, giving him the confidence to cut “hot records that move air, don’t sound like shit, and aren’t compressed to death.”

He gets in and out of the Elysia Alpha Class-A discrete compressor without destroying the musicality. And “the Pacific Microsonics A/D converter I use is going on 20 years old, but it clips beautifully, is Class A, and has a ton of analogue headroom. There are units more perfect than mine, but I would argue that in my chain, for my ear, and for the things I front load it with, there’s nothing more musical for me.”

He uses two main EQs — a Fairman TMEQ tube equaliser, and a Focusrite Blue 315 Mk2 that’s heavily modified because “the stock version sounded like total junk. I don’t get why it was so revered. But I love the controls and functionality on it, so I had a guy named Rob Harvey go through it, gut it and see what he could do. He ended up taking out 40 capacitors and replacing all the 5534 op-amps — a super generic jellybean chip — with $16 Burr-Browns. Saying it really cleaned it up, would be an understatement.”

Lucey describes the solid state Focusrite as clean with a slightly forward quality, while the Fairman’s tubes are also clean, but it has a laid back quality: “So between the two, the image stays where it was but you get all the harmonic content.”

The last EQ he resorts to is a linear phase EQ in Sequoia, which is the first digital EQ he’s ever liked for his work. And it’s been a part of his workflow for four or five years where a minor cut or de-essing is required.

He uses the hardware Waves L2 limiter, fixed to knock off a dB and a half. Again, he’s had people question his choice of limiter, but he likes the sound of it, it isn’t doing much, and recently, when the power supply went down, he just couldn’t get his chain sounding the same. “I don’t need any more than a dB and a half out of it because I’m clipping the converter,” said Lucey. “If I like the sound of it, then that’s the best thing.”

After the L2 is a Cranesong Hedd, a little trick he uses to round off the square waves with a little bit of harmonic distortion.

Lucey: “There are only eight pieces in my chain, including the computer, and synergistically they all become one thing. At this point, it acts as an instrument for me. And my instrument is good at ‘loud’ and moving air, if that’s what needs to happen.”

Two 17-inch Macbook Pros flank either side of Lucey’s listening position. They’re as big a screen as he wants in his reflection area — they sit below the throw of both the mid range driver and tweeter — and he doesn’t want any screens in front of him. He runs Seqouia on one using Bootcamp, and the other for day-to-day communication. And with such low loads on his CPU, fan noise isn’t really a problem.

He has a label on each computer, one reads, ‘Each email an honour’, and the other, ‘Each single important, every record a career’. Lucey: “People don’t have to send me an email. No matter how annoying they might be, I don’t treat them that way. It’s not my place to judge them or their music. It’s my place to connect to it.”

MASTERED FOR EVERYONE

While the loudness wars rage on, there’s another battle going around higher sample rates, but Lucey reckons we’ve got bigger fish to fry, specifically iTunes.

Lucey: “Generally speaking, Mastered for iTunes is just about starting with the high-resolution file. But there are people using the ‘Mastered for iTunes’ label as a source of income, and I think that’s unethical, because I’ve done hours and hours of A/B testing, and tweaking the source to match the faulty codec is the wrong approach. The right approach is to provide the best sounding source and have the codec get better over time.

“My hope is they improve the codec; it’s quite cold and thin. I don’t think the guy writing the code hears the way some of us hear. Some people don’t hear harmonic content as being particularly valuable, and the guy at Apple is going for a perfectionistic approach. On paper, the codec is much closer to the source than an mp3 at 256kbps — mp3 is more distorted, no doubt. But in my opinion there are many things about an mp3 that sound much better.

“Distortion on paper is not the enemy, everything we do is distortion, it’s part of the alchemy — frequency, distortion, transients. When I listen to music through the Apple codec I hear thinner low end, shortened bass notes and it’s harmonically colder. When I listen to an mp3 I hear the opposite, fuzzy and bloated. It’s like a hippie that’s gone four days without a shower and shows up at the party. But there are some qualities to that we could really use in Apple’s codec, which has a real white labcoat, ’80s CD aesthetic. Let’s hope Apple improves, or we go to streaming 24-bit.

“As for the whole Hi-Def movement, that’s a whole other silliness, upgrading and printing something at 96k is silly. Converters sound like they sound. A converter has three components: the actual chip; the analogue circuitry that leads from the input/output to the chip and back; and the clock that runs the process. The user input to those three fixed things is sample rate. But those three things never change from 44.1k to 192k. You still have the same chip, clock and analogue circuitry in the path. By changing the sample rate, you’re simply changing the presentation of those things.

“It’s like mastering, I could master a record five ways, but I wouldn’t change the song, the artist or the mix — I might make it a little brighter, mid-rangier, darker, fatter, or a little louder or softer. I would still just be playing with this fixed thing, which is the mix. So when you’re chopping sound up into more slices, all you’re doing is playing with the frequency and depth presentation. Now the depth part of it, 99 times out of 100, it doesn’t matter because you don’t have enough dynamics in the first place for it to really matter.

“If you’re talking about recording a symphony, okay, but I’d still rather have an awesome converter running at 44.1k. Any asshole can print at 192k with a $150 converter, is that better than my $17,000 ‘development cost was no object’ converter running Class A at 44.1k?

“This seems pretty simple to me. There’s a whole economy springing up over high sample rate delivery — it’s bullshit. Look at all the records Daniel Lanois recorded to a DAT machine. Wrecking Ball with Emmy-Lou Harris sounds great, but was mixed to DAT. By the Apple iTunes standard that can never be mastered for iTunes because the source is 16-bit. That’s dumb! Some jackass can send you a 24-bit source of the worst-sounding mix in the world, it doesn’t make it a better record. The numbers game is very male, like a version of penis-measuring, it’s not important.

“Yeah, you hear more high frequency detail, more reverb tail. But it’s still those three components that matter most. Stream at 24-bit and be done with it. The 16 to 24-bit change is nice, after that it’s kind of silly.”

In the same way that Lucey doesn’t think about codecs when mastering, he pays no heed to alternate listening systems either. “Tighten Up, the single on The Black Keys’ Brothers album has been licensed more than any other song in The US.,” said Lucey. “So I’ve heard Tighten Up everywhere — bars, grocery stores, strip clubs, car after car, and show after show on TV. And no matter where I hear it, it still sounds how I meant it to sound. It still has good low-end and good low-mids, it’s still loud, it’s clear, it’s still harmonically nice, even when it’s been data compressed down to whatever shitty format they’re using. I don’t make a thing less bright, so if it gets brighter it’s okay, and I don’t make a thing fatter, so if it gets thinner it’s okay. I don’t worry about that.”

CONNECTING WORLDWIDE

Mastering engineers are the midwives of the audio world, controlling the moment between gestation and becoming real in the world. Lucey doesn’t take that responsibility lightly, he knows once it leaves his hands it will never be touched again, and the world can judge it. It’s a big part of the reason Lucey has foregone the “whole notion of a mastering room being a $150,000-concrete foundation, multi-walled layered cave” and persevered with his own non-isolated mastering room design.

“To me this is what mastering is,” he reasons. “I’m at the threshold between the creation and the world. I can literally look out and see the world go by. I’ve done the windowless cave, perfect room, and it’s not my aesthetic. My aesthetic is naturalism and connection.

“When you get into a scientific mindset of perfectionism, you end up with an amplifier that has a million details into the horizon line, but not the palpability of the mid-range, which is where the people are. Details are ridiculous, no-one listens to details. They listen to music and music is mostly mid-range.

“So my setup — from the location, to the amplifier, to the way I think about it — is all about that connection, because there’s not enough humanity in the windowless cave.”

RESPONSES