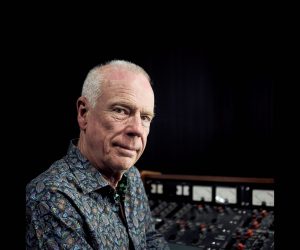

Ben Frost: School of Emotional Engineering

Whether it’s music for art installations, movies, or the masses, Ben Frost’s ability to produce other-worldly sonic weirdness has taken him far – Iceland in fact. AT cold calls Ben to learn more.

How on earth does a kid from Western Victoria end up plying his trade in Iceland?! Actually, when you take a listen to some of Ben Frost’s productions that question becomes easier to answer. Ben, either solo or at the controls of his School of Emotional Engineering project, delivers dark, unhinged, crunchy, affecting soundscapes. His work has led to remixing and left-of-field collaborations, which has now seen Ben spend the last 12 months in Iceland stationed at Valgeir Sigurdsson’s Greenhouse Studios in Reykjavik — a world-class facility that made a name as Bjork’s studio of choice.

I reached Ben on the phone as he returned from recording the Icelandic Children’s Choir in a church 100km out of town.

ICY RECEPTION

CH: Ben, what’s happened to your accent?

Ben Frost: I know… I can’t hear it until I start talking to another Australian such as yourself. My Icelandic has had a huge effect on my English.

CH: Why Iceland?

BF: The short answer is: I like being here. It’s a really good place for me and my work has benefited hugely. I’m around a lot of people I like working with – I like the people, the culture and the language.

CH: Are you a free agent or are you stationed anywhere specific?

BF: Most of my work is centred around Greenhouse Studios. I work as a co-conspirator with Valgeir Sigurdsson. Valgeir is responsible for everything Bjork’s done since around the time of the Vespertine album. Valgeir is a great friend and collaborator but I consider myself his student – I’ve made it my business to learn everything I can from him.

CH: And what are you mostly doing at Greenhouse?

BF: Mostly I’m processing sounds and beats – manipulation of existing material. I’m not a traditional assistant engineer. In fact, Valgeir isn’t a traditional head engineer; mostly we use gear in a way that gets us to a certain result. I’ve never sat down to learn a piece of gear just for the sake of knowing it. I need a reason. I’ve never been interested in being an engineer.

CH: I think with the sheer quantity of software and hardware available you wouldn’t be alone in that approach. You have to choose your weapons and become proficient in those.

BF: Sure. I produced my first record on a Pentium 166 running Fruity Loops v1. The entire album was mixed and mastered within that. Since then I’ve always picked things up along the way… if I’m learning compression or EQ, it’s a process of hearing its impact and listening to what it can do for me in a musical sense. Which is different to the traditional approach of an engineer, where you learn about compression and the science of sound and then apply it to music. For me it’s always been the other way around – the music comes first.

CH: Tell me about your tools of the trade.

BF: I’ve been working with Ableton Live since it was released. That’s the mainstay of everything I do. The next School of Emotional Engineering album is being constructed in Live and the sound of that program really suits the album. For example, I’ve tried importing the Live files into ProTools for the purposes of mixing, and, after listening to rough mixes in both applications, there’s something about the architecture of Live that crunches the sound in a different way. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but you especially notice the Live ‘sound’ at work in the low frequencies – anything below 40Hz – becomes more solid… it has more body. For me, and my ears, Live is working really well. I’m not saying it’s better sounding than ProTools but it’s my kind of sound and my modus operandi.

CH: So whether it’s Live or ’Tools, are you mixing within the computer or are you using faders?

BF: Greenhouse Studios has recently bought a new SSL AWS900 24-channel analogue console. I would love Ableton to start supporting the HUI interface so I can interface with the SSL. For the time being I’m running Live as a tracking device, using the SSL’s analogue inputs. Then I’m Midi’ing the SSL control surface and using Live a bit like ’Tools.

CH: When it comes to tracking and mixing do you wish Live functioned a little more like a conventional digital audio workstation [DAW]… like ProTools?

BF: There are times when I wish it would take that extra step. But at the same time I like the fact that Live sticks to what it’s good at. That can be the downfall of a lot of software. Developers have a tendency to try and compete with each other and do what other packages do, rather than concentrate their products’ strengths. I’ve been working with Live for so long (I was beta testing it on v1) that it’s now virtually transparent; I don’t even see it anymore. I don’t get that with other packages.

CH: If you started out on Fruity Loops and spend a lot of time mashing sounds, I hazard a guess that Midi doesn’t play a big part in your life.

BF: You’re right, it’s not a key part of my work. Since Live introduced Midi into v4 I’ve been making use of the on-board sampler [the Impulse drum sampler], using it to write kick patterns and the like. I also like to use the Random feature. It’s a really interesting way of working. It’s just a matter of loading a bunch of clips in there, randomise them and see what happens while recording the output. Worth looking at.

almost all of the drums on the new record were recorded through the mic input on my iBook

CH: Do you rely on Live for EQ and processing?

BF: I use the compressors and EQs, but as a rule I try and find as many ways of doing things as I can. I’ve actually been using Cycling ’74’s Pluggo suite. A lot of those EQs and compressors are crude and ugly but they’re unique, which I like. Other times I’ll send something through an outboard device like a [Teletronix] LA-2A and crunch something to pieces, which adds something else.

For me, it’s not about the gear it’s about whether it sounds cool. I never use gear because of its reputation or because someone’s told me that it’s something I should be using. For example, almost all of the drums on the new School of Emotional Engineering record were recorded through the mic input on my iBook – the actual built-in mic on the laptop. And that’s simply because it sounds right to my ears. You wouldn’t want to hear that on a Bob Dylan record, but for what we’re trying to achieve, it’s perfect. It’s loud, brash and very different.

CH: Again, it adheres to your ‘means to an end’ philosophy.

BF: Exactly. I don’t care how it’s done, as long as it sounds right. I’m interested in ugly sounds… cold sounds. So it makes no sense to try and achieve ‘cold’ and ‘ugly’ using vintage valve gear that costs the earth. That doesn’t work for me.

CH: So you’re not trawling eBay for obscure tube-based studio throw-outs then?!

BF: No, but I’m a big sucker for early digital – gear from that period of the ’80s when studios were just starting to cross over to digital. I love the crudeness of that gear. All those Joy Division records or the Cure, when they were starting to use early digital synths, reverbs and samplers like the Fairlight. There’s something about that sound… It’s mostly shunned or frowned upon these days, but there’s something about it – I really love it.

CH: And finally, it’s the middle of winter there at the moment; I guess the lack of daylight suits studio work pretty well?!

BF: At the moment we get three or four hours of twilight a day. And it does have a big impact on your metabolism. I find I can sleep up to 14 hours a day without stirring. I’ll just wake up at 11:30am when the sun starts to rise. It’s very strange. But Iceland is a beautiful place. I’m looking at the Northern Lights through my window at the moment. It still sends shivers down my spine.

RESPONSES