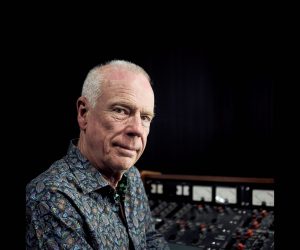

Ben Allen: The Sound of Atlanta

As an engineer, Ben Allen was at the forefront of the New York rap scene for many years. Initially working for Puff Daddy’s Bad Boy Records, Ben later moved to Atlanta, home of crunk rap, where he helped Gnarls Barkley frontman, Cee Lo Green, record his contributions to the hit album, St Elsewhere.

Text: Tom Flint

Photos: Angela Morris

Ben Allen has a habit of being in the right place at the right time. When rapper/singer Cee Lo Green began a casual collaboration with DJ and producer Brian Burton (AKA Danger Mouse), Ben happened to be working as Green’s engineer. The project – eventually christened Gnarls Barkley – produced the worldwide hit single Crazy and acclaimed album St Elsewhere. No one could have predicted the record’s huge success, despite the reputations of those involved, but Ben was there from the onset. Primarily recording Cee Lo’s vocals and instrumentation at his own Maze Studios in Atlanta, he then later mixed the album at Glenwood Place Studios in Burbank, together with Danger Mouse and his engineer Kentaro Tokohashi.

There was also the time Ben resigned from his job as assistant engineer at the Cutting Room Studios in New York without having anywhere else to go, only to find himself filling the empty assistant engineer’s chair at Puff Daddy’s Bad Boy Records a mere two days later! He stayed on for two and a half years, graduating to engineer, and working on projects from the likes of Lil Kim, Mase, Carl Thomas, and, of course, Puff Daddy [I think you’ll find that’s ‘P-Sean Puff Diddy-Daddy Coombs’ at the minute – Ed.] himself.

Even Ben’s demo tapes share his gift for timing. When he, and writing partner Tony Reyes, penned a track called Here To Stay it was thrown onto a demo at the last minute and posted off to Christina Aguilera, who selected it to go on her Back To Basics album.

So, what’s the knack Ben? Well, probably best to start from the beginning…

BAD BOY BEGINNINGS

Tom Flint: How did you start working in studios?

Ben Allen: During a year off from college I began helping some friends build a studio in the middle of a desert in New Mexico. I worked there for about a year and decided it was what I wanted to do for a living. From there I got an intern job at New York’s Battery Studios, working about 90 hours a week for a minimum wage. It was shit work but they’re testing to see if you’re serious. I left after 12 months and started as assistant engineer at The Cutting Room.

TF: How did you get the job at Bad Boy Records?

BA: A friend from the first studio called me the day after I quit saying ‘my buddy who works for Puffy tells me they need an assistant, what are you doing?’. I told him my situation, so the next day they sent a car and suddenly I was in the Bahamas working for Bad Boy, initially as assistant engineer and later as engineer.

TF: So you weren’t specifically trying to break into the rap scene?

BA: I was a bit. When I was in New Mexico I researched studios around the country and surmised that in LA you’re going to do rock, in Nashville it will be country, and in New York it’s hip hop, and that’s what I was interested in, so I consciously headed there.

TF: Did you leave Bad Boy so you could diversify?

BA: I decided to leave when I came into the studio one day and noticed that everyone had a gun except me! I’m originally from Georgia, so I exported my knowledge of hip hop to Atlanta, got set up pretty quickly and found work mixing crunk records, which is Atlanta’s take on rap. If you want to be an engineer here that’s what you do.

HIP HOP ROCK

TF: How do the skills and techniques you learnt from recording hip hop cross over into pop and rock production?

BA: To me, they all go together, which is why everyone calls me The Blender. I like putting 808 sounds with acoustic guitars. Right now I’m producing a Bowie-esque synth pop band called The Management and I’m trying to put a bit of bottom-end oomph in the production so that it has a deeper, harder sound. That’s the kind of stuff I get from rap records.

TF: Apart from a heavy bottom end, rap is notorious for its sparse midrange, an area normally populated by synths and guitars. What’s your approach to dealing with that sort of instrumentation?

BA: When I work with rock bands it annoys me to hear guitars playing all the time because I’m used to having space in the mid range. That midrange is sacred. For me, as long as the drums are hitting hard and you can hear the vocal then anything else is just ear candy. That’s a very Rick Rubin style – kick, snare and vocal. On every record he’s made, apart from a Johnny Cash recording, they are the loudest things. In my view, his success with rock records lies in the fact that they end up sounding like rap!

I’m constantly telling the guitarist to shut the hell up and let the singer sing. It may sound like I don’t want to hear guitars, but what I’m trying to do is get the singer to be better. The more you take out, the more pressure you’re putting on the vocalist to deliver a compelling lyric or melody. Until you get all the shit out of the way a lot of vocalists are not motivated to perform. I also encourage bands to think differently and play the same part on piano or Wurlitzer. It doesn’t always have to be guitars.

TF: So you’d encourage a band to look at their arrangements?

BA: I tell them to try playing their songs with no guitars in the verses and see how it sounds. Nine times out of 10 they love it because when they add the guitars in the chorus it sounds massive. It’s just getting them to see the magic in that, which is sometimes near impossible.

TF: Who else has influenced the way you work?

BA: I’m a huge fan of Tchad Blake. He made a couple of records with Mitchell Froom in the early 1990s which had a really big impact on me because they were sonically very adventurous and creative. You could tell that the sounds were part of the recording process, and I like that. I look at engineering as part of the production so I’m constantly trying to carve sounds to fit a space at the moment of the recording. I don’t like cutting a bunch of stuff and then sifting through it in ProTools three days later, I’d much rather do it right and have one vocal track. My goal is for every song to be mixed by the time it’s recorded.

TF: How do you do that?

BA: The most important thing to get right is the performance, so if I’m recording a dynamic vocal I’ll get the singer to work the mic so the loud parts are not loud on tape. If we’re recording a guitar I might put one mic on the amp and one in the room but compress the crap out of the room one with an [Urei] 1176 using a really fast attack and release to give it a big boom like an old Stax record.

I decided to leave when I came into the studio one day and noticed that everyone had a gun except me!

GNARLS BARKLEY

TF: How did the Gnarls Barkley project come about?

BA: Danger Mouse and Cee Lo had been talking about doing something for some time. Cee Lo was unsigned and could do what he wanted, so the timing was really good. Danger Mouse started sending us tracks, we began cutting vocals, and next thing we knew we had a record.

TF: So there wasn’t some grand strategy then?

BA: I’d venture to guess that Danger Mouse had a plan but he certainly didn’t share it with me early on. When Crazy was done they knew they had a record. Danger Mouse, more than anybody, knew how good it was and it made them really motivated to finish an album.

TF: Crazy seems to have very little going on under the vocals but it has a punchy bottom end, so did you approach it as you would a typical rap record?

BA: Mixing it was interesting because I had to take everything I’d learned and throw it away! Danger Mouse pushed me to do a lot of things I didn’t agree with, although now I realise it was really brilliant.

TF: Give me some examples.

BA: First of all, for an urban artist like Cee Lo, there isn’t a lot of low end on any of the album songs, except perhaps Who Cares?. The album doesn’t hit very hard compared to Atlanta music.

The second thing is that I’m used to making things sound a bit cleaner, but the goal with Gnarls Barkley was to make an old-sounding record that seemed new at the same time. So I set out to make Cee Lo’s vocals the newest sounding thing in each song – in the songs that feel old, the vocals feel new. Listen to any of the songs on a good set of speakers and Cee Lo’s vocals always appear the shiniest, brightest element there.

TF: So what were you using to tonally shape the record?

BA: It was a combination of EQ and plug-ins and that combination was different for every song. The idea was to carve out both the low and high end from the sounds so they felt crunchy and old.

TF: Crazy still has a lot of punch on the radio.

BA: It’s punchy for sure, but it doesn’t have a lot of low boom. Today, even pop music is all low end and fully urbanised, and I was used to making things sound that way. I was looking at Danger Mouse saying ‘are you sure about this?’ and he was like, ‘trust me’.

TF: How do you get something to be punchy without it being muddy?

BA: The most important part of any rap record is for the producer to use a good arrangement, then you don’t have to do that much. My perfect mix is one where I put the faders to unity and then print it… although that never usually works!

I’ve developed a sense of the different spaces that low-end can inhabit. ‘Punch’, ‘thump’ and ‘boom’ is how I describe those areas. ‘Punch’ hits you in the chest, ‘thump’ in the stomach and ‘boom’ lower than that! Cee Lo and I have a vocabulary based around that idea so I can say ‘are you talking about more punch or thump or what?’.

Technique-wise, I have to decide what is going to occupy the very low boom – is it going to be the bass or the kick/808, because they can’t both be there. Will the bass carry the thump and the 808 the boom, or vice versa? The biggest challenge is carving out a space for each of those instruments.

TF: What’s special about those old Roland TR808 drum sounds?

BA: They mark the Atlanta sound. If you’d never studied Atlanta rap records and tried to make beats here you’d never survive because you wouldn’t understand, literally, the cultural and social implications of a snare sound! You can’t just use any snare, it has to be the right one, and it can’t just be any of the 300 used in the last year. That level of detail matters.

TF: Many people use heavy compression and double tracking to get the vocal to be really in-your-face on rap records; is that something you do?

BA: Compression is very important, but vocals are the one thing I don’t like to compress much on the way in; everything else is fair game. Usually, for vocals, I compress enough for it to be listenable when we’re working, but not so much that it’s going to tie us to that sound. As I work I’ll just group all the background vocals and send them through one auxiliary bus with a compressor and maybe a Waves L1 [limiter] on it to keep it all up-front and in-your-face.

TF: The Gnarls vocals have a distinctive sound; any special ‘sauce’ you can tell us about?

BA: That’s just Cee Lo. He’s got one of the best recorded voices I’ve heard, and it’s really hard to screw up. We used some specific EQ and effects but the biggest thing was to achieve a consistency across all the songs. So all the vocals were recorded using a Neumann TLM103 fed into a Neve 33118, which is an old preamp and EQ, and then it was compressed using a Universal Audio 1176.

SET TO A MAZE

TF: When did you set up Maze studios?

BA: About four years ago. It’s basically a bunch of really nice rehearsal rooms containing gear. There are a lot of studios in Atlanta that have the marble floor area and multi-million dollar design but I can’t stand that working environment.

TF: Too sanitised?

BA: I just don’t like the luxury! I’d rather feel like I’m in my living room. So the idea was to make it like a living room, and that’s also a lot cheaper to build. One of my goals was to keep my overheads low so that I can work on the records I like. I’d rather pick and choose projects and have [US]$2000 of overheads a month from both my apartment and studio, and for that I’ve got 3000 square feet of studio.

TF: Presumably you’re putting together your favourite bits of kit at Maze.

BA: I’m running ProTools 7 on a HD3 rig with Apogee converters and Big Ben clock. We have Neve 33118 mic preamp modules, a couple of Vintech Dual 72s, a Urei 1176 and an Avalon that you just have to have in Atlanta or people don’t think you’re worth bothering with… although I don’t think it sounds that good. I love the 1176 though. I’ve also got a couple of Grace Design preamps, plus a set of SSL 4000 Series line amps and mic preamps we use for tracking stuff out of Akai MPCs. I use a lot of Lawson microphones. They are a company from Nashville who hand-make Neumann U47 and Telefunken 251 copies. They sound phenomenal and I’ve been using the U47 non stop recently. Between the Lawsons and my Neumann TLM103, we usually get what we want.

My biggest thing is to use lots of instruments, so we have several drumkits, 10 or 12 guitar amps and guitars, a lot of analogue synths plus a Rhodes piano and Wurlitzer. Maze is designed to encourage people to touch stuff. One band came in and wanted to set up every keyboard in the room, and that’s what I want.

I don’t have a lot of outboard preamps and EQs but I like to find creative ways to use the limited gear I have. I like being in that environment and that state of mind. I just want to have three options and make one work. When the studio is imperfect it makes you more creative. I don’t think that Gnarls would have been so compelling if we’d had a $3000-a-day room with girls bringing us fresh fruit… which is what it’s like in LA.

RESPONSES