Baptism by Immersion

In just six hours, Adam Rhodes had to learn how to mix ‘immersive’ before stepping out with an L-ISA system at the famed Royal Albert Hall. Pressure’s on!

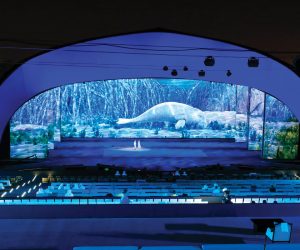

Photos: James Adams

In mid-July, The Classic BRIT Awards was due to descend on the Royal Albert Hall in the UK. It would be a televised event, with crossover artists like Tokyo Myers layering virtuoso pianoscapes and epic drum sequences over orchestral backing. It was the perfect gig to showcase L-Acoustics’ immersive sound system L-ISA, and beam the audience’s response into living rooms across the nation.

Of course, an event like that doesn’t go to air untested. There had to be a guinea pig, and Adam Rhodes was it. Brit Row called up Rhodes to ask him if he wanted to demo L-ISA when Angus & Julia Stone were playing the hall just three days prior. Sweetening the deal, Brit Row said the PA wouldn’t cost a cent more. Music to the ears of any promoter. The deal was done, and a month later Rhodes was sitting in a pre-production suite, staring at a bunch of L-Acoustics speakers with six hours to get his head around a revolution in live sound.

“We were the first people in the UK to use L-ISA,” said Rhodes, who’s an incredibly technically astute guinea pig. As well as being an international FOH touring engineer and a handy technician, he’s worked a lot with surround in post-production for TV and film. “Although it’s a big step from those formats, they knew it was something I would be familiar with.”

It’s also not the first time he’s been at the pointy end of a new technology, having been one of the first to try out L-Acoustics K2 in an amphitheatre in Lyon (L-Acoustics is a French company). He’s had a loose relationship with L-Acoustics ever since.

REAL WORLD DEMO

Inside the L-ISA system engineers can place up to 96 objects anywhere on the immersive canvas. In this case, the canvas was a ‘hyper-real’ L-ISA setup; constituting the minimum number of five hangs of KARA across the front, and an array of K1 SB18 subs above the central hang flown “way up in the sky,” said Rhodes. “I first thought it was ludicrous, but it was very usable.” There were also outfills and infills, but the five main hangs and flown subs represent the core L-ISA system.

When Rhodes rocked up to the demo suite at Brit Row, he was presented with a downsized version of the L-ISA rig. It was still hooked up to the L-ISA processor, but rather than line arrays, he was listening to a collection of L-Acoustics monitors — the kind he’d use for infills — set up on stands. “It was basically a virtual environment of what it was going to be like at Royal Albert Hall,” he explained. “I took my Avid S6L in there, set it up with the software and went through it with the two developers who’d been working on it.”

Recently, Avid announced plug-ins for L-ISA would be available on the S6L, but this was pre-plug-in. Despite Rhodes dragging in his S6L console, other than playing back a virtual soundcheck, all the work was done in the L-ISA system. The interface between the two worked fine though, “On my S6L I have multiple snap shots of songs, and they include, among other things, panning positions; solos, rhythm sections, and so forth,” explained Rhodes. “With a USB MIDI port, I plugged into their system and was able to steal snapshots really simply and easily.”

SETTING UP THE MIX

Initially, Rhodes moved cautiously. “Because we’d been on tour for several months, I didn’t really want to toss the show to the wind and start again,” he said. “I initially used the streams to recreate what we already had.” By default, when you drop a source onto the L-ISA stage map, it places it on the ‘30% line’ and in line with the centre hang. The 30% line is 6dB down from unity, or 100%. Bringing it closer to the front of the stage is just a level change, and pushing it further back starts to introduce reverberation as well as pushing the level down.

“It really allows you to mix in a far more musical way,” said Rhodes. “Dragging things forward really brought them to the front. With stereo things like drum kits, if I had put the kick and snare in the centre hang, I’d be overpowering it. by using groups, I could put them in two and four, and use the phantom centre for my kick and snare. Then I could put the vocals in the centre hang and it would cut through it like a knife. It was magnificent.

“For people who are sitting off-axis on the left and right of the auditorium, it’s not like you’re listening to one hang and only hearing that side. It’s actually coming out of the centre of the stage.

“I basically ran everything out post-fader, post-processing in individual streams. Drums and basses were the only things that were grouped. I had a pair of stereo groups for my kick and snares with a bit of parallel compression on it. Then I panned the rest of my drum kit on it on a second pair of groups, with parallel compression on them.”

Once Rhodes was comfortable with his basic positioning, he started to play around with the mix. “When there was a banjo solo, rather than turning the level up, I just used a snapshot that brought it to the front of the system,” he explained. “Then the next snapshot I pushed it back where it was.”

Initially, he had his stereo Nord keyboard spread out far left and right, like he normally would, “then it started to feel a little unusual, so I started placing them where they visually appeared on stage, in hangs one and two, or three,” he said. “That way the sound was coming from where it looked on stage. There were a couple of things I put in other places because I’d run out of room. There’s lots of keyboards on stage right, so I couldn’t put them all into the stage right hangs.”

From there he began working on his effects: “I had my standard reverbs out in hangs one and five. Then, because I had the vocal as a dry source in the centre, I started putting other verbs into hangs two and four.”

IN THE FIELD

Six hours later, the moment of truth had arrived. Rhodes moved over to the Royal Albert Hall. As well as being the first time on L-ISA, it was also his first time mixing in the legendary venue. “It’s on the bucket list for a lot of FOH guys,” he said. “I’ve got to say though, it’s a tough room. A lot of people were telling me I was going to hate it, that the reverb time is six seconds.

“The in-house guys and the L-Acoustics people were saying the multiple hangs actually dealt with a lot of those issues, and made it a lot clearer and present. I can’t really comment on that, but it didn’t feel like I was struggling with the space. My bass drum was about four seconds long, but it wasn’t unusable; I was quite comfortable with it.”

In the demo suite, with Angus & Julia Stone fitting somewhere between pop ballads and rock, and therefore more upfront, Rhodes placed all of his 49 stems on the 30% line, with the exception of bringing guitars and vocals forward. He’d refrained from pushing anything back into the spatial processing. When he hit the venue for a two-hour soundcheck, that’s when he “really started pulling things around. It became evident how powerful it was. I could pull things forward, shift them between hangs. I pushed back some of the ambient pads, which makes it less identifiable as a source point. It’s just kind of hanging in the air, which was really nice.”

IMMERSIVE IMPRESSIONS

After the show we asked Rhodes what his impressions of the L-ISA system were.

AudioTechnology: What was your biggest concern going into it?

Adam Rhodes: My biggest concern when I was first presented with the concept, was the gain before feedback figures. Angus is a very quiet singer and I’m usually on the edge, but I had more gain before feedback than I’ve ever had before. It was one of the few times where I felt I had gain for days. I guess that’s because you have so many hangs, instead of pushing everything into the left and right and getting all that cross talk from the two hangs back onto the stage. Everything is pushing forward.

AT: Compared to a traditional stereo deployment, are you more or less aware of the physical speakers?

AR: You’re less aware of the physical speakers and their interaction because the sound stage is broader and more visible. When I’m mixing in a stereo environment, I spend a lot of time walking from left to right as far as I can. One, because of the Power Alley down the middle when you’ve got the subs left and right. Or the coupling effect when you’ve got big hangs. I actually don’t like being in the middle; I want to be just off to the side in the first valley, where most of the crowd are. I didn’t have that issue with this configuration.

AT: How did the centrally-positioned low end cluster feel in the mix?

AR: It felt very natural, it didn’t feel unusable or different at all. We weren’t running it like a dance or EDM show, although we have a lot of sub energy with the Moog Taurus bass pedal. It still delivered more than I needed. On the L-ISA system, they had set up an auxiliary sub, and I pulled it back about 4dB from 0 to bring it into line with where my mixes normally sit.

AT: Did the rigging time seem like a hindrance?

AR: “It’s a massive step up from what we know now. It took a long time to get it into the air at Royal Albert Hall, but that was the first day it was hung. The PA tech from L-Acoustics was very exacting about all his points, his hangs, and how it was going up. There were three hangs on the front truss, and it all had to be cabled up. If you were touring it, you’d have that all pre-rigged and it would go up a lot quicker. I can’t see it being much slower than a normal PA going up. It would take a little extra time, but you could have them pre-rigged, with all the hanging hardware installed on the truss, and pick it up on a few motors.

AT: Did you have any idea of the cost of the system?

AR: “It is more expensive, but in somewhere like Royal Albert Hall, I would have wanted K2, or even K1, to cover that area, whereas we had 90 elements of KARA. Talking to Brit Row, they would estimate that to be not much more expensive than putting up 30 elements of K1. It’s not a massive leap, it’s not even twice as much because you’re using a smaller box. It’s more expensive, but not crazy.

AT: Do you think it’s worth it for productions to shell out for the extra time and cost?

AR: If you want to make your show a spectacle, and do something different, it’s the way to go. I can imagine the people who sign the checks baulking at it, but if the artists start to see some acts do it and hear the benefits, they might start pushing for it. We’ve been doing left/right hangs since Moses, so it’s very impressive. Just ask anyone who goes from stereo to 5.1 surround in their lounge room. They start to hear all the nuances and space, your sources are all coming from where you imagine them. It’s equally so in the live environment.

AT: Would you do it again?

AR: In a heartbeat.

Immersive sound system – another “reinvention of the wheel” as is the line array.

Please revisit the Grateful Dead sound system of the early 1970s as detailed in “Sound System Engineering” by Don & Carolyn Davis in 1975. That was truly immersive sound!

Hey Rick, of course. There’s no denying this is a complete reorientation back to some of the principles of the Wall of Sound. As is the stick PA concept. The surround aspect of these systems also has a legacy in Quadraphonic sound, though the room simulation side is well-advanced, as is the object positioning and depth sides of the mix. At the end of the day, if it draws the punter in closer to the music, then that should be applauded. Our full immersive live sound special is due out in the September issue of AudioTechnology