Ball Park & Live With It

Ball Park Music recorded their last album themselves, at home, on a computer. This time they travelled to the other end of the country to record live to four-track tape in a barn. The question was: Could they do it?

Artist: Ball Park Music

Album: Every Night the Same Dream

“Daddy… can I come in now?” came a whine over the talkback. “Don’t be a Donald, one more take!” snapped back ‘Daddy’. “Roll tape!”

Brisbane-based band, Ball Park Music, and producer/engineer Matt Redlich, are like one big, slightly unhinged family. Sam Cromack, is the lead singer/guitarist and occasional toddler impersonator who dragged the band all the way down to a converted garage in rural Victoria to record a whole album live to four-track analogue tape. Naturally, he’s bonkers.

On the other end of the line Matt — not his Daddy — decides whether or not a sound or take works by judging how ‘randy’ it is. As he puts it, “It’s a fine line between being too randy, and not randy enough. If you’re not randy enough, you may as well go home. I’d rather be too randy.” Who wouldn’t?

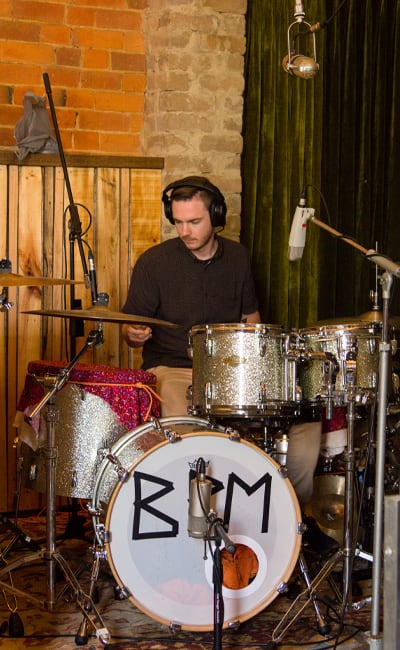

Rounding out the rest of the band are Paul Furness, sight-reading genius keyboardist who prefers the quiet of Brisbane but hates what the new lockout laws will do to live music. Bass player, Jen Boyce, piano teacher and singer-songwriter who thanks her lucky stars she asked to swap music groups at uni and ended up in this band rather than an all-female vocal ensemble or the typically dysfunctional ensemble of rock guitarist, funk bassist, metal drummer and grunge chick she would have been lumped in with. Then there are the twins, Dean and Dan Hanson (guitars and drums, respectively… I think); both killer players who I did catch saying the same thing at the same time — ESP does exist.

To explain exactly why a band whose last album Puddinghead went to number two on both the ARIA charts and Triple J’s Best Album poll, ended up driving all the way down the East Coast of Australia just to record live to four-track analogue tape, Sam had to start at the beginning. As it turns out, AudioTechnology was partly to blame.

REWIND THE TAPE

Five years ago, when Ball Park Music were thinking about recording their debut album, their manager suggested they contact fellow Brisbane-ite Matt who, at the time, was primarily recording to a 16-track, two-inch machine. Sam — despite studying music and production at uni — had never seen or recorded on a tape machine in his life. “We’d recorded with other people and it was always a mega-modern digital affair with a ‘100 mics on the drums’ scenario that totally lacked vibe,” said Sam. “We went to all this effort and it sounded shit. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, our band properly sucks! These recordings are so bad we’ll never, ever make anything good.’ When we met Matt, we rocked up with this short, sharp, little rock song. He tracked guitar, keys and drums all at the same time, and the keys were going through this broken old amp that was pointing right at the drum kit, which ‘only’ had three mics on it. We were thinking, ‘Can you even do this?’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about a click, just play,’ which was a real turning point for us. It sounded more awesome than anything we’d done before.”

It was more than just the tape, said Sam, “Matt’s fun because he’s a bit of a rule-breaker, like getting me to play acoustic guitar out in the garden. He pulls great sounds but has a playfulness about him and is keen to go on an adventure with the song. I don’t like working with people that are too clinical, it’s just boring.”

They recorded that album, Happiness and Surrounding Suburbs, as well as their second Museum with Matt to tape. Then we put a crazy idea in their heads. “A guy touring with us had a copy of AudioTechnology magazine and there was a special on DIY musicians,” said Sam. “All five of us took turns reading the article and after reading it we were all thinking, ‘We can do this!’ Particularly reading about Kevin Parker. Obviously he’s super-talented and skilled, but I was just really surprised at his lack of technical focus. What the article said about the way he would do things was very much focused on the bigger picture, not worrying too much about the gear or the technical element, which can intimidate people.”

Sam had always done a lot of recording at home on his laptop, but once they’d decided to record themselves, they went out and spruced up the rig. A new computer was purchased, Focusrite Saffire interface set up, software installed, a basic mic collection pulled together, a house rented, then they “just kind for went for it.”

Puddinghead ended up being their most successful album to date. However, when the band started playing songs on tour, Sam realised there was something missing, the same thing they missed whenever they overdubbed on tape — that live feeling.

“I thought producing it ourselves would give us this greater level of creativity, but one of our biggest regrets is simply not experimenting enough,” said Sam. “Even though the record did well for us, it doesn’t necessarily sound like we do. As soon as we started playing shows I was immediately thinking, ‘this has something we’ve never really put on a record.’ Even when we recorded with Matt to tape, his old machine had 16 tracks, and we might play guitar, bass and drums together, then wipe the guitar and bass and overdub on top of the drums. Nearly every time, the record you do previously informs how you want to do your next one. This time around we really wanted to do it super-super-live.”

GET THE PICTURE

Sam didn’t necessarily have a picture of what that would look like or how they would capture a ‘super-super-live’ recording. Then one day the picture emerged fully formed — it was staring him right in the face, on Facebook. Some of Sam’s friends were ‘friends’ with the owner of a little country Victorian studio, Sound Recordings, and a photo of the control room flashed up on his feed. “You could see the tape machines and the desk,” remembered Sam, who was instantly charmed. “I really wanted to come to a place that felt great to be in. So much of the gear looks old school; big silver things with gigantic knobs, it’s hard to not be like, ‘Cool!’” He began stalking the studio online, and when he saw the live room, it “was hard to not fantasise about tracking in there as a group.”

Sam started researching every album he could find recorded to four-track tape, but the results weren’t altogether helpful. “The spectrum of how bad or good they were was super wide,” found Sam. Coming up short on that question, ‘will it sound any good?’ His next move was to ask Matt to check it out — who was in the midst of moving down to Melbourne anyway. “I’d heard of the studio before, but not much more than knowing C.W. Stoneking recording Gon’ Boogaloo here,” explained Matt, who was equally curious about whether he could do the job there. He did have one vote of confidence, “Ryan Strathie, who’s the drummer in Holy Holy, the band I play in, knew all about it,” said Matt. “He’s a big vintage nut. We were all impressed with how authentic that C.W. record sounded. You’d just never know it wasn’t record back in who knows when.”

Matt was sure they couldn’t do what they needed direct to two-track, but he was intrigued about going back to four tracks, something he used to do before he decided he needed the track count and ‘mod cons’, like a counter on his 16-track machine. “I always loved the sound of it,” said Matt. “The four-track sounds like all of your favourite recordings from the early ’70s. It immediately sounds like something just by going through it. The low end is exciting and big, it seems you can push it quite hard without it getting unmusical in any way. It has this spongy head room. It kind of means you can treat it a little less carefully.”

Playing it safe wasn’t really on the cards, and Matt and the band wanted to focus on the performances going down, so having headroom to push into is key. Luckily, Alex’s gear has plenty of headroom, most of his control room is equipped with hand-built custom gear by Ekadek in New Zealand, designed to maximise headroom and sound good even if you hit its limits. “It’s the nature of what we’re doing,” reminded Matt. “We don’t have the time or equipment to do it precisely. It’s got to be all about vibe, and you have to make a judgement in the moment of whether it feels good or not, then more or less live with the judgement forever.”

STACKING TRACKS

Once everyone was onboard with the idea, the real work started up in Brisbane. “You’re forced to make everything that goes onto those four tracks count in a way you don’t have to in digital or a 16-track machine,” said Matt. “If the idea isn’t absolutely working or definitely making it better, then it can’t go on that track because it’s recording on top of something else.” The combination of tracks is vital. Sam always planned to track vocals at home, so that was one instrument taken off the list. Regardless, there were still at least five others, plus any room mics and effects, to squeeze onto four tracks. The maths demanded some combinations be made; whether it be rhythm guitar and keyboards, or drum room flange effect and lead guitar, a few instruments had to get cosy.

Ever since Puddinghead the band had been writing songs for this record and fleshing out demos along the way. Prior to rehearsing as a group, they prepared in smaller clusters. “For instance, Paul would come to my house and we’d spend hours getting all the keys parts and sounds right,” explained Sam. “We pretty much did that for every instrument.” When everyone got together for group rehearsals two months out from the recording, they all knew what parts they were playing. “It was a bit like the prep you do after recording, when you learn the album to go on tour,” explained Sam. “We’d just did a quick recording on our phone and if it sounded shit, it sounded shit. We had to get it better.”

Meanwhile, down South, Matt was using the demos and his mental image of Sound Recordings to form a plan of attack: “My main thoughts were around how we were going to record it, how it was going to sound, what parts had to be in the bed, and what parts probably shouldn’t be.” While most of the tracks encompassed the entire music bed, there was no hard and fast rule that everything had to be printed at once. Occasionally Matt and the band would decide to leave a part to be overdubbed because it wasn’t mixing in with the other instrument on its tape track. Once everyone knew what parts were going down, the way everything sounded through headphones was crucial to getting the vibe right in the room explained Matt: “It changes the feeling in the room when all the sounds are working and every part comes through clearly.”

REAL TIME REALITIES

The band invited AudioTechnology along to spend a couple of days out in Castlemaine while they tracked the soon-to-be album, Every Night the Same Dream. Things seemed to be motoring along fairly consistently while we were there. They had 12 days to record 11 songs, and each day we visited the band managed to lay down a couple of songs. We arrived on the second day and they already had Feelings, the opening track, nailed. It was sounding as visceral as they could have hoped, full of rich low end and powerful mid range. Most of all, it sounded like a talented band playing with well-rehearsed abandon.

Sam says it wasn’t always that smooth: “If you don’t get it within the first two or three takes, it’s going to be 10 takes. There’s been a few songs in particular where we’ve hit massive walls. Everyone’s fatigued, frustrated and it feels like you’re getting further away from it. You have to dig really deep and inevitably get it in the end. If you look objectively at the amount of time you spend to get the take, it’s easily the same or less amount of time as tracking each part, one at a time. It’s certainly more fun.

“The challenge of having to do it as a group is great. Nearly every final take where we go, ‘That’s the one!’ has a bunch of errors in it anyway. In many cases, we get it to a point where the five of us nail it, but it just lacks vibe. The ones that have that extra magical something are the ones where we just stopped giving a shit.”

We’re not chasing, ‘okay we can hear every drum now.’ We’re chasing a ‘Woah!’ reaction every time someone walks in the room

CREATIVE FEEDBACK LOOP

The session moved along remarkably smoothly while we were there. The band had hired a house in the surrounding area, not realising Alex also runs a B ’n’ B onsite. Each day they rocked up at about 10am in the van, and piled out into the studio to find their spot.

When Matt and Sam were setting up, the drums found their home in a corner of the room. The bass amp — a Marshall JMP head set at a clean level and the cab miked up with an AKG D12 — was set up along the wall close to another corner, with dividers diminishing leakage a little. The guitar amps were setup in the other two corners, with Dean’s cordoned off into a gobo cubby hole and Sam’s occasionally having one dragged in front of it. Matt’s main focus was balancing the volume of the amps then using gobos to kill the top end and make the sound less directional. Dean mostly played through Matt’s Dr. Z head and cab, while Sam alternated between the 100W Gunn combo house amp for a unique jangly tone, and a Fender Deluxe to fill the role of the “one sound that’s not very extended and ‘good-sounding’,” explained Matt. “Many amp’s sound good really cranked. But in a situation like this, that’s actually what’s going to kill the sound of that instrument because the low-mid bleed into every other mic will make it sound bad.”

With the song worked out beforehand, the band would start preparing their sound — changing cymbals and tom heads if required, and tuning to the song; pulling up patches or preparing the piano; and finding the right amp to play through. Matt would immediately get to work listening to each sound and determining what worked and what didn’t. A guitar sound could start out played on a six-string through a 100W amp, and end up recorded on a 12-string direct through his homemade valve DI. Likewise, the keys could go from being played direct off the computer, to Paul having to switch between keyboards mid-song, with one amplified through a hacked vintage projector and miked up at a distance. “The Bell & Howell projector has a built-in valve amp,” explained Matt. “We’ve put the Korg MS-20 through its little speaker cabinet. It’s kind of thin-sounding but it’s small size makes it easy to overdrive. When you do resonant filter sweeps through it, it picks up particular frequencies and clips them. It creates animation in the sound you wouldn’t get with a DI or a clean setup. The keys have also gone through this Gerard amp which is another weird-sounding amp that’s apparently part solid state, part valve power amp.”

No two songs were the same, and therefore no consecutive tracking sessions stayed in the same configuration. The two constants of the drum mic setup were a kick mic of some sort — typically either a Bock iFET or an AKG D12 dynamic — and a kit mic. Matt likes to think of it that way, as opposed to an overhead, because it’s not there for the cymbals, it’s to pick up the whole kit image. “Most of the time, you should start minimal and try to get as much out of each one mic rather than starting with 12 or 16,” said Matt. “The thing with over-miking kits, if you’re putting all 12 mics in the best possible place and having half an hour to listen to the different places you could put the mics, that’s a whole days worth of just miking a kit up. Unless you have that time, having heaps of options is a bad thing.” Matt was also limited by the passive mixer, which required unplugging the final input patch cable to solo instruments; a distracting process when you’re trying to listen for phase anomalies. “It’s not as easy as pushing a button and concentrating on what you’re hearing,” said Matt. “Also, once you get a balance, if one of the mics is quiet, you can’t just turn the fader up for a second to check it. Your only option is to use your ears and tweak the knobs until it sounds good. Which should be the case all the time anyway, but we don’t because we have the power to not.”

Ball Park Music are all talented, and Dan is the perfect lynchpin. Technical and solid, but with a heavy groove that would make Bonham proud. He can go everywhere the songs do, whether it’s laid back beats, to pounding tom fills. He’s also impeccably in tune with his drums, swapping between standard coated and fibre heads depending on the track, and playing his toms heavier than his cymbals. Having a great drummer lets Matt rely on one or two kit mics, sometimes it would be an RCA77 over the kit, or a U47 over Dan’s shoulder, occasionally a blend of both. Matt also might sneak an omni pencil condenser up between the rack toms, or sit a Sennheiser MD421 a foot above them. Sometimes he’d have a Shure SM57 close miking the snare, other times, none at all.

Matt started out the sessions EQ’ing and compressing each mic on the drums before hitting the mixer, then running the summed mono kit through his 1176 and JLM Audio Pultec-style EQ, prior to tape. He’d also occasionally run a UAD distortion plug-in on his laptop for monitoring. Towards the end of the sessions, he backed off the processing slightly, preferring to pre-EQ into the mixer, and only compress to tape.

MIXING A MIX

Matt was never shy of printing with effects. On one of the songs they recorded while we were there, Matt had “a room mic going through a bright-sounding Space Echo that was printed on a track with the guitar. It may not have been perfect, or the exact volume I wanted it to have, but I thought it sounded good and it created an energy and space they played off. It’s that classic thing of the drummer playing to the Space Echo and it becoming almost like a click track. I like to create a feedback loop, where I can inspire them to creatively take it somewhere with new ideas, and they inspire me in turn. It’s much more fun than getting it nice and clear in the headphones.”

Early on, they did try stereo drums, but quickly went back to mono. “Once you get into that mindset, suddenly you’re treating the drums as a single instrument, which is really what they are,” said Matt. However, even though he was recording the drums in mono, as Matt was archiving them onto his computer, he started playing around with stereo-ising effects to see if he could add some width back at the mix stage, and many of the drum tracks did get treated with a subtle micro shift effect to create space around the mono track in the mix.

At the mix stage, Matt found some songs sounded great straight off tape, while others required a little more pushing. The groovy pop of songs like Peppy and Suit Yourself seemed to suit the recording process, whereas the rockier Nihilist Party Anthem was particularly difficult. Matt had gone for a reasonably punchy, clean drum sound, but the band wanted them dirtier. It’s a hard task when you’ve got all your drums on one track. “Even just the cymbals in close mics can be a problem in multi-track recordings, so when you have an overhead mixed in and start distorting and use lo-fi effects, the cymbals get crazy!” said Matt. “Getting something interesting that’s also not a hash of white noise in the chorus is always a challenge. I ended up going as far as I could and sending them a version that showed what happened when I took it up a notch from there. I was still concerned about maintaining punch and how it would sound on radio and smaller speakers.” It was also one of the more complex mixes, as the band had gone on to record lots of vocals, double guitars, and add sound effects back home, resulting in a session that resembled a regular multitrack. On the tougher songs, Matt had to surgically dissect some tracks to give him control over a bass or kick, because “if you change the low end on one mic, it can drastically affect others when you’re mixing two or three together.” Overall, Matt was surprised that the low end was either bang on or just shy, given he felt he was pushing more to tape than he usually would.

Matt used his Apollo 16 interface to archive all the takes.He brought two 1176 compressors; a Universal Audio reissue (“Smoother sounding for vocals and guitars”) and a Hairball Blue Stripe copy (“Great for drums”). Matt’s lunchbox is loaded with an AML ez1073-500 (“1073 clone I use on bass, drums, anything”), Hairball Lola (“a clean, fast pre”), two Hairball 1081 clones (“good on drums and guitars”), a Harrison EQ, Hairball 500 and JLM Audio FET500 1176-style compressors. “The JLM is a bit cleaner and extended, it has more headroom and is faster,” said Matt. “It’s good on kick drum and we were using it over the whole drum bus yesterday with great results.” At the end of his rack are two Radial ‘trick’ boxes — the EXTC, to blend in some Soul Blender distortion on snare, and X-Amp 500 for reamping.

ENGINEER A LIVE PERFORMANCE

Matt thrived on the challenge of returning to four tracks and the level of commitment it required. He was reminded of how good it can sound when you mix things down live, and has started printing drum and guitar mixes alongside individual mics in all his recent projects. “It’s really cool to put yourself in that position as an engineer and not just be deferring things till later, later, even later… till mastering. It should be, ‘Let’s get it exciting right now!’ I’m having to give a live performance as an engineer, reaching down into that subconscious pool of experience developed over years. You come up with ideas and opinions you can’t even explain in words, they just bubble to the surface in a situation like this.

“That’s how you create compelling results for the listener. It’s exactly what the band are doing when they write the song in the first place. Those song ideas bubble out of this collective pool of experience, and the playing comes from years of performing live and knowing what the crowd responds too.”

Even though Matt is a co-producer with the band, he sees the job of engineering as integral to helping everyone realise the vision for each song. Building up sounds that are unique enough to create interest, but meshed enough to give the band that feeling of togetherness while performing is integral to the vibe in the studio. “On one of the songs I set up all the mics, set all the compressors, EQs and gains without hearing anything, and it sounded f**king cool,” explained Matt. “Sam was like, ‘Woah!’ That was the reaction we needed to preserve. Tweak it a little bit to fine tune some things that are out of control, but that’s what we’re chasing. We’re not chasing, ‘okay we can hear every drum now.’ We’re chasing a ‘Woah!’ reaction every time someone walks in the room. They want to have a big smile on their face because of what we just recorded.”

RESPONSES