A Day In The Life Of Geoff Emerick

Geoff Emerick has recorded some of the most iconic albums in the history of modern music. During his tenure with The Beatles he revolutionised engineering while the band transformed rock ’n’ roll.

Main Photo: Beth Herzhaft

To an audio engineer, the idea of being able to occupy Geoff Emerick’s mind for a day to personally recall the recording and mixing of albums like Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Road is the equivalent of stepping inside Neil Armstrong’s space suit and looking back at planet Earth.

Many readers of AT have a memory of a special album they’ve played on or recorded, a live gig they’ve mixed or a big crowd they’ve played to. Imagine then what it must be like for your fondest audio memories to be of witnessing The Beatles record Love Me Do at the age of 15 (on only your second day in the studio); of screaming fans racing around the halls of EMI Studios while the band was barricaded in Studio Two recording She Loves You; of recording the orchestra for A Day in the Life with everyone, including the reluctant musicians, dressed in party hats and red noses; of going live-to-air across the world to billions during the recording of All You Need Is Love; of miking up Yoko Ono (on John Lennon’s insistence) so that her comments were audible as she lay in bed in the corner of Studio Two, ‘recuperating’ after a car accident. The memories that roll around in Geoff Emerick’s head are amongst the most remarkable, historically significant and bizarre in the history of audio. If only there was a patch lead to access them all.

Speaking to Geoff Emerick on the phone via his home in Los Angeles reveals a humble man with a passion for music that’s as youthful today as it was when, at the age of six, he started listening to his grandparents’ collection of old gramophone records. These old LPs sparked a life-long passion for recording that continues unabated to this day.

HE’S LEAVING HOME

Geoff Emerick began his recording career at EMI, at the now legendary studios of No. 3 Abbey Road, at literally the same time as a group of chaps from Liverpool called The Beatles turned up for their first real recording session (they had already done an audition with George Martin at EMI, so this was theoretically there second visit to the studio). On only his second day of what was to become a long career boxed inside a studio, Geoff – then only an assistant’s apprentice – witnessed the humble birth of a musical revolution.

From there his career shot into the stratosphere, along with the band, becoming The Beatles’ chief recording engineer at the ripe old age of 19; his first session as their ‘balance engineer’ being on the now iconic Tomorrow Never knows off Revolver – a song that heralded the arrival of psychedelic music. On literally his first day as head engineer for The Beatles, Geoff close–miked the drum kit – an act unheard of (and illegal at EMI) at the time – and ran John Lennon’s vocals through a Leslie speaker after being asked by the singer to make him sound like the ‘Dalai Lama chanting from a mountain top’. To the utter amazement of all concerned he pulled it off. It was a masterstroke and from that moment on Geoff was ‘in’.

So how did such a young bloke, apprenticed in arguably the most conservative recording facility in London, manage such a radical feat?

Geoff Emerick: Basically out of a determination to succeed, and give The Beatles the sound they were imagining for Tomorrow Never Knows. The Beatles were always under pressure to produce hit singles, and were always looking for new sounds, but because the technology wasn’t really there to do most things, you had to invent ways of accommodating their requests by stretching your imagination basically. But, of course, most of the things I did for The Beatles were actually ‘illegal’ in terms of the EMI rulebook. There were strictly enforced processes and protocols in place – many of them growing frustratingly old-hat by this stage. The things I did on my first day working on Tomorrow Never Knows could easily have got me sacked. For instance, you just weren’t allowed to put a microphone closer than 18 inches from the kick drum. That was the rule. When I started going closer, needless to say there was a big kerfuffle…

AS: It’s hard to even conceive of that being a problem today… was this rule based on an equipment maintenance issue or something?

GE: Absolutely. EMI was a big, big company that regularly used to sell 500,000 to a million copies of hit singles and they didn’t want anything about these cuts being technically ‘flawed’ or damaging to either their own, or listeners’ equipment. The cost of recalling that many discs would have been disasterous. Because we were cutting to vinyl we couldn’t have excessive sibilance or bass etc, but the problem was, there were rules and regulations for just about everything else as well, including strict rules about the clothes we wore. But because we’d been listening to American records that were louder and had more bass, we eventually started challenging these technical edicts right around the time The Beatles became hugely successful.

The Beatles were hearing these American records, as was I, and the differences were obvious, so we were determined to do something about it, even though the powers that be hated change. All we had to compete with though were the Fairchilds and a few Altec compressors – that was about it. Consequently, I would do anything to make something sound bigger. I mean, I’d put three Fairchilds in series sometimes, not knowing what was going to come out the other end but occasionally what came out was magic! The drums in particular used to sound enormous through them.

By the time we started recording Pepper our approach had become all about doing things better; every song an attempt to improve on the one before. Even if we got a great drum sound on a previous song, we wouldn’t use that same sound again. Every track was like a new challenge demanding a new approach.

AS: In essence, it was a pure pop mentality…

GE: You’re right. But back then we were limited in so many respects. For instance, the equalisation on the Red 51 console only had treble and bass controls on it. We did have an outboard equaliser as well, which had 2.7, 3.5 and 10kHz controls, but that was it. If you wanted different sonic textures on tracks you had to utilise different microphones, ones that were duller or brighter – a discipline that is rarely applied these days. It’s funny, because if you read some of the literature that’s out there about all this, you’d think we had equipment coming out our ears, but we didn’t. There’s one particular book that talks about all the gear we used, half of which I’ve never even seen before!

A REVOLUTION

AS: It amazes me how quickly you became good at creating new sounds, particularly when you’d grown up in such a conservative establishment as EMI. How did that come about? Were you secretly plotting to turn the world on its head while you were Norman Smith’s assistant or something [Geoff trained under Norman as an assistant during the early ’60s]?

GE: No, not at all, although I would often look at how Norman was going about it and think to myself, ‘I think I’d do that a little differently if I were in the big chair’. The thing is I would always just listen off the studio floor first to get a ‘trigger’ from the music, or from what the guys were saying to one another or to me. It might have been a harmonic off an instrument or a conversation between the band members – anything that might catch my ear. A good example of this was getting the sound for John’s vocal on that fateful day when we recorded Tomorrow Never Knows. John asked me to make him “sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a mountain top” so after a short panic attack and looking around the facility for something that might generate such a sound – there were no ‘Dalai Lama mountain top’ echo units handy you see, only a bunch of guitar amplifiers – I decided to try putting the vocal through the studio’s Leslie cabinet, which no-one had ever done before to my knowledge. As it turned out, it worked brilliantly, with ample portions of echo thrown in there too.

Recording with The Beatles was a collaborative artistic pursuit, which involved crafting sounds rather than just saying, ‘oh well we’ve got three guitars, drums and bass… that’s the sound’. I wouldn’t have lasted five minutes if I’d had that mentality. Song production is about blending sounds and instruments and merging them together. It’s an art form. The point is, any engineer can paint by numbers, but if you want those magic brush strokes like the ones you see in famous paintings, you have to put them in, they don’t make themselves all that often.

AS: It sounds like you were pretty good at interpreting abstract requests…

GE: I was I guess.

ADDING SALT TO PEPPER

AS: Sgt. Pepper sounds like it was very eclectic in terms of the engineering approach in that, as you say, no two songs or recording techniques were ever repeated. What sparked this sudden explosion of sonic exploration in you and the band do you think?

GE: It was a lot of things really, but partly it was because The Beatles weren’t intending to tour again so they suddenly felt liberated to make their records more experimental. If they didn’t have to play the songs live they could essentially do anything. And that experimentation was reflected on the engineering side of things as well. And, of course, at the time – and I’m using Pepper here as the example because it was a huge album in terms of sonic advancement, as was Revolver to a lesser extent – it was an extremely exciting process to be part of. I remember after we’d recorded A Day in the Life on that magical night… we’d just done the monitor mix and Ron Richards – who recorded the Hollies – was sitting on the floor in the control room looking up at the ceiling saying: “I think I might have to give this game away now. How do you top that?!”.

Everyone was absolutely silent that night. Control room Number One wasn’t very big, so most people were sort of huddled by the door or outside it, listening to the rough mix and there were no words to describe it. It was so magical and wonderful. It was like going from a square black and white picture to a Technicolor Cinemascope picture for the very first time.

AS: And this monitor mix was mono I presume?

GE: Sure.

MONO–LITHIC

AS: Which brings me to the whole concept that seemed central to achieving the Sgt. Pepper sound – submixing. With mono in mind rather than stereo, how did you choose what got bounced together, or was a stereo mix still in the back of your mind somewhere?

GE: No, not at all. The stereo mixes, which were done by myself, Richard Lush and George Martin came out later. But a small point to make about those mixes – while we’re on the subject – is that even though they only took three days to complete, they weren’t ‘rushed’ as some people have inferred over the years. That’s just how long they took to complete. But certainly during the recording of Pepper stereo was hardly even considered because it was the preserve of classical recordings at that stage. Mono was the format to which all our work was referenced and the format that influenced the way things sounded. For instance, it was always very hard to get two electric guitars to be easily distinguished from one another in mono and that was a great motivator to make things sound distinctive. It took a long time to get them to work together sometimes, but thankfully we had the luxury of time to get things sounding right during Beatles sessions. It’s very easy to put one guitar left and one guitar right in stereo, but in mono, things were different.

If, for instance, I couldn’t achieve distinction between two guitars out of a single speaker, or if there was a keyboard in there that was getting lost, I would often speak to John or George and say, “The guitar sounds aren’t working with the keyboard, can we alter the EQ on the amps?” There was more control over the sounds from the studio floor back then than there was from the control room.

AS: Given that mono mixing made panning a non-issue then, how did you choose what went with what on a track of tape during a tracking session or submix pass?

GE: We always knew roughly that we were going to record drums, bass, a couple of guitars and whatever else, and generally we’d put the two guitars together on their own track, and bass and drums together as well. In the early days I put bass and drums on the one track for the simple reason that if I didn’t have enough bass or drums when it came to the four-track mix, I could always bring the drums out with some treble EQ and the bass out with more bass EQ. We did four-track to four-track one-inch transfers sometimes too to enable us to do a few more overdubs, and on some of these songs a lot of stuff would end up submixed onto one track. But four-track one-inch tape has very wide tracks, and that’s why the signal-to-noise ratio on that stuff was still pretty good.

We’d maybe bounce together a couple of guitars, a keyboard, whatever would fit… and on Pepper we always overdubbed Paul’s bass afterwards because he typically hadn’t worked it out until towards the end. This was really handy for us because it allowed us to overdub it separately and use the whole studio space to capture it. Richard Lush and I used to record the bass with Paul late into the night after everyone had gone home.

RECORDING THE BASS

AS: Can you elaborate a bit more on how you used the studio space to record the bass?

GE: I had this sound in my head for the bass that I couldn’t get with the band playing as an ensemble, but because Paul wanted to record it separately on Pepper it gave me a good opportunity to do it a bit differently. I was searching for roundness but also looking to put a sort of halo around the instrument. Up until Pepper the bass had always been close-miked (with an AKG D20), mainly to minimise spill, but once we started overdubbing it in isolation I switched to an AKG C12 set to figure-of-eight. We would record Paul’s bass in the middle of Studio Two on the hardwood floor, with the amp miked up from about four or five feet away, as I said, in figure-of-eight, and that added the halo effect by putting a little bit of room around it. You can’t really detect it but it’s there. I think the bass sounds great on Pepper. I’d been fighting to get a sound like that for ages and I finally got it!

GETTING BETTER

AS: What other memorable tricks did you perform on Pepper while you guys were turning rock ’n’ roll on its head?

GE: I remember once putting splicing tape all over one of the tape machine’s roller guides to create massive ‘wow’ – on the machine that was feeding the piano solo signal on Lovely Rita into the echo chamber. The splicing tape was designed to inhibit the machine from playing smoothly, and sure enough, it was wobbling all over the place! I hate to think what would have happened to me if the manager had walked in on us that night! That wobbly piano echo was never used again, interestingly enough, only on the Lovely Rita solo.

We also sync’ed up two tape machines for the overdubs on A Day In The Life; that was certainly ‘interesting’, shall we say.

AS: How did you sync’ them?

GE: I think, from memory, we had a 50-cycle pulse that went to the motors of both machines. We had a Chinagraph mark on both tapes that physically marked the beginning the song, and we simply cued them up and physically pressed the play buttons simultaneously – pretty sophisticated by today’s standards I know! If one machine got ahead of the other we’d simply restart them. It was really just trial and error. If you actually listen to the orchestral buildups on A Day In The Life you can actually hear that one of those tracks is out of time slightly. One orchestral track was on the four-track master and the other four tracks of orchestra came from the second machine, which wasn’t 100% in sync.

AS: So the 50Hz pulse gave the machines some kind of control, but nothing to write home about…

GE: It sort of worked, let’s put it that way. Funny thing was, you’d never be too sure if they were still in time until we got to the orchestral part of the song, simply because all the band stuff was on the first four-track.

On Pepper I used to change mic setups a lot too, all driven by the challenge of making the next track better than the last. But it wasn’t just a gratuitous exercise; there were always artistic reasons for these relentless change-ups based on the particular track we were doing… listening to it in the studio and saying, “It would be nice if the piano was less bright for this track – let’s try miking it from underneath with different mics, that might sound good.” That’s the way I always approached things.

AS: But it clearly wasn’t the way you were trained to approach things. Sgt. Pepper was obviously a watershed recording where a synergy between you and the band collectively ‘recalibrated’ the entire recording process. Is that a fair statement?

GE: It was for sure, but there was innovation before that as well. For instance, I remember Norman Smith subverting the EMI edict that all mixes had to go through the Altec compressor, again because with vinyl you didn’t want too many bass swings, and it made it easy to master the thing. I remember Norman saying to me, “I’m gonna put everything through the Altec except the bass, because some of the notes are getting lost.” The bass was immediately a lot clearer but he didn’t dare tell management what he was doing – there would have been an inquiry! That approach was a manifestly huge leap forward. He was also the one who taught me that when a band’s rehearsing down in the studio, you can normally open up just one mic and know whether you’ve got a hit on your hands.

YOU CAN’T DO THAT

AS: It seems ironic that The Beatles found themselves trying to be totally radical within the confines of what was seemingly the most old-fashioned studio in England.

GE: Right, exactly. And that was one of the other problems. They’d invariably meet other bands who would tell them that they’d worked at this or that studio, and that over there you could do X, Y and Z, no problem. So, of course, they’d come to us and say, “Oh, we’ve been talking to so and so and they do this and they do that, why can’t we do that as well?”

AS: It’s amazing in hindsight that they tolerated the place for so long!

GS: I’ll tell you why they did. Because whenever they went outside the EMI studio to record something, they could never get the same great drum sound or same great bass sound. They could never – especially some of the guitar sounds we were getting – match what we were capturing.

AS: Sounds to me like they kept coming back because of your engineering skills, not the studio. It wasn’t that EMI had superior equipment or better facilities – indeed, based on the conversations we’ve had, it seems like it was always the last place you’d find a new piece of cutting-edge equipment.

GE: Either way, they always came back, no matter how dire their issues with the place got.

AS: I can see you’re not going to take any direct credit for their apparent studio loyalty, so we’ll leave it at that!

GE: Except for when we get to The White Album of course! [Laughs]

THE RE-RELEASES

AS: What’s your feeling these days about the Beatles remasters being released without your involvement?

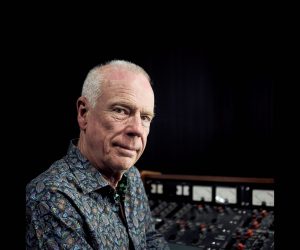

GE: Well, it’s absolutely stupid when you think about it. Incredibly, Abbey Road Studios constantly claims to have recorded The Beatles. Frankly, that’s insulting. Abbey Road didn’t record The Beatles, I recorded The Beatles, along with several other engineers including Norman Smith, Ken Scott, Richard Lush, George Martin and, of course, The Beatles themselves. Abbey Road didn’t record The Beatles, people recorded The Beatles!

At best I’d call these re-issues ‘generic’ since none of the original people were involved in the process. Frankly, I find it incredible that the original recording engineers are hardly even mentioned on these re-releases. It’s all the remastering engineers that get the credit. It’s quite bizarre.

When they first put out the publicity for these remastered Beatles albums, one of the press releases from Abbey Road went so far as to describe them as new recordings, which was absolutely ridiculous. I think after a while they withdrew that.

MIXING A WHOLE

AS: Changing the subject slightly again, can you give us your insight into the benefits of mixing songs as you track them, rather than after an album is recorded?

GE: To me, recording a track and mixing it in the one process is definitely the best approach. The recording engineer and the mix engineer were the same person once upon a time, of course – until some made a hit record by mixing someone else’s tape one day and the record company geniuses got the idea in their heads that this was the best way to do it. When the recording engineer is also the mix engineer you retain all the knowledge about the recordings that you need to take into account when you’re mixing it – the roles are locked together. When they’re separated there’s a tendency for the mix engineer to miss crucial cues and for the recording process to get out of hand, because the recording engineer doesn’t have to pull the work together, and in many cases doesn’t even know if it can be!

AS: So obviously you still advocate mixing a song immediately after you’ve tracked it, while all the memories are fresh in your mind?

GE: Yeah, for sure. Certainly working on The Beatles stuff, we’d mix a track immediately after we finished the last overdub. We couldn’t even wait ’til the next day to do it most of the time! You’d mix it that night. This approach definitely helps you feel fresh during long sessions too; helps you feel like you’re making good progress, rather than just building up a giant pile of work ahead of you to tackle further down the track when you’re already sick of it.

AS: How do you think the Beatles would have fared if they’d had the option of an endless track count and digital automation?

GE: I suspect it would have been a mess!

RESPONSES