Last Word with David Dearden

with David Dearden

My father had a wunderlust. I must have attended more than 10 schools in five different countries across Africa and even Australia for a while, before dropping out as a teenager and moving to Zambia.

By that point I knew I wanted to be involved in recording. My father had purchased a lot of old equipment from the South African Broadcasting Corporation. We had a good collection of old ribbon mics — RCAs, BBC Marconi Type AXBTs — and an old disc cutter that was in pieces. At the age of 15 I put that back together and made it work. That stimulated my interest in all things recording.

Zambia didn’t have a recording industry, so I considered my options, made my way to Johannesburg and knocked on the door of the largest studio in town and asked for a job. They said ‘okay’.

The studio was owned by David Manley [Founder of Manley Labs] and was huge, it occupied six floors of a city building with a different discipline on every level. As part of my apprenticeship I went through each floor.

“…I would go to John Lennon’s house and stay overnight… I sometimes wish I’d picked up the odd scrap of paper with lyrics scribbled on them for my retirement.”

As was common back in the late ’60s, the studio was building its own recording console — prior to the era of standardised equipment. This console was based entirely on V72 valves. I could handle a soldering iron, so I was roped into building the console.

I went to the London in 1970. London was the centre of the recording industry and it was my plan to work there. That’s as far as my ‘plan’ went. I flew out of a Rhodesia in the throes of independence, when its currency wasn’t valid and you couldn’t take money out of South Africa either. So I landed at Heathrow with five pounds in my pocket.

I knocked on the door of a studio called Advision in London and asked for a job. They said ‘yes’. Actually they offered me the choice of being a tape op or a junior tech. I asked which paid more — tape op got 12 pounds a week and the tech job attracted 15 pounds a week — so I took the tech job. Turns out the senior tech Eddie Veal had recently resigned. I was thrown in the deep end.

Fortunately, Eddie returned on a contract basis when he was engaged to upgrade the recording console. The console was designed by Dag Fellner and was one of the first transistorised multitrack recording consoles of the time. It had 20 inputs and eight group outputs and Eddie was upgrading the monitoring section to work with our new 16-track Scully tape machine. As the studio tech, it was my job to assist, which was a great experience.

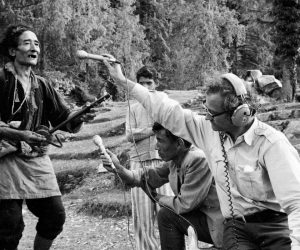

Eddie went on to do a lot of studio design. One of the first he did was John Lennon’s private studio in 1971 to record the Imagine album and he asked me to assist.

It was probably one of the very first private studios in the world — it’s not like there were many commercial studios in London at the time — and a big departure from the Abbey Road atmosphere where even then men in lab coats stalked the building ensuring you didn’t over-modulate this or use the wrong mic on that.

During the recording of the album I would go to John Lennon’s house and stay overnight just in case there were any technical problems that might arise. I sometimes wish I’d picked up the odd scrap of paper with lyrics scribbled on them for my retirement.

From 1975 I worked full time with Eddie Veal building consoles and studios, including a studio for George Harrison at his home and another for Ringo who moved into John’s house when he and Yoko moved to New York.

In the late ’70s I spent time with MCI and then Soundcraft. Soundcraft was going through a rough patch financially, so myself and Gareth Davis would contemplate what our next move might be if Soundcraft went belly up. We decided to start our own company, DDA.

By 1982 we’d gone full-time producing a small mixing console first spec’ed for high-profile classical just meant for classical recording engineer Tony Faulkner.

DDA became quite successful in a short time. Within four years we had introduced a big split-design recording console called the AMR24 which hit the right part of the market at the right time.

The first time we exhibited that console in 1985 I recall the people from Soundcraft dropping by to comment that “the world doesn’t need another multitrack recording console. You’ll never sell any of these.” We couldn’t make them fast enough.

With the success of the AMR24, I got a call from Phil Clarke wondering if we’d be prepared to sell DDA. Klark Teknik had just gone public, the Clarke brothers had a war chest of money and were determined to grow quickly. I told Phil we didn’t want to sell. We didn’t think anyone would be willing to pay what we thought DDA was worth given where we were taking it. Turns out they were willing to pay what we thought it would be worth and we became part of the Klark Teknik empire. That was then absorbed by Mark IV Audio Group. We’d never intended to be part of a big corporate machine but we were. That’s where we stayed until 1997 when we escaped and started Audient.

The late ’90s wasn’t the right time to be launching an analogue console but we didn’t know how to do a digital one. People did think we were crazy, but we had enough feedback from studio people to suggest there was a market and the ASP 8024 was born. The console was designed to be affordable thanks largely to the use of printed circuit board rather than the traditional modular method. It’s proven to be a good design, in fact, it’s still a strong seller today.

Audient is best known in the UK. When I’m in the US I still have people talking about their DDA console, and I’ll encourage them to retire it — you’ve had your money’s worth out of it!

I’ve never considered myself to be a audio design guru, just a cluey tech, so to be still deeply involved in designing is as satisfying as it is surprising. Maybe it’s that Antipodean thing we share — an attitude of just getting on with it.

RESPONSES