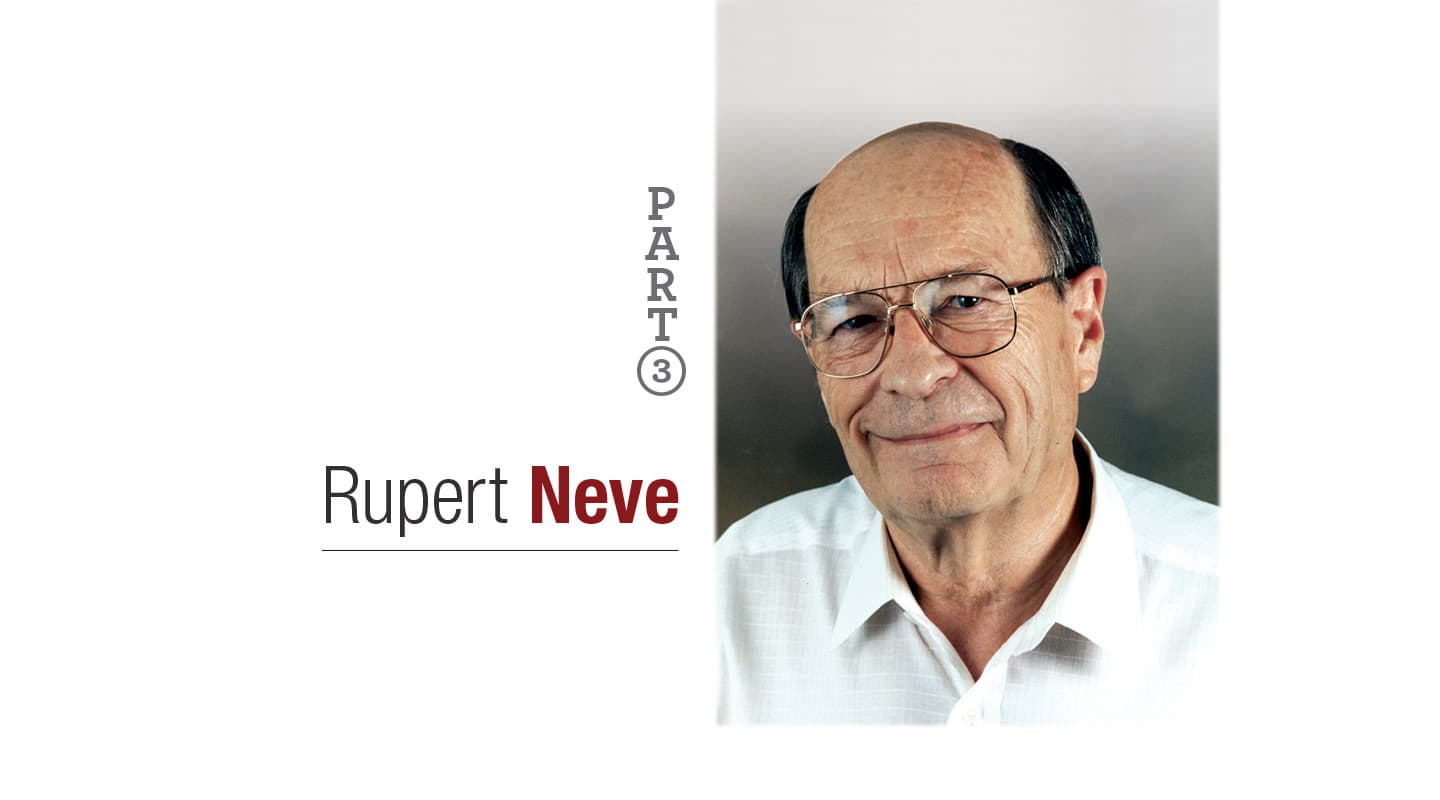

Rupert Neve Interview Part 3

Musicality, warmth, transparency... In the history of pro audio, one name has always been synonymous with these qualities. In the third and final part of our interview, Rupert Neve talks to Greg Simmons about low cost audio, AMEKʼs System 9098 series, the legacy of making good products, and the nature of creativity.

Rupert Neve. The name is associated with some of the most cherished and long-lasting pro audio equipment ever made. Consoles he designed and built 30 years ago are still going strong today. In a world where digital consoles are becoming truly and necessarily disposable, it’s good to know that some people are still designing analogue consoles to last for decades.

Part Two of our interview concluded with Rupert Neve commenting on equipment design: “The trouble with a lot of designers, you know, is that they don’t listen. They think their maths books will give them all the answers. You do absolutely need to listen, and to be prepared to listen to what other people are saying, too. And then you will be able to come up with some really first class designs” Part Three follows on from this point…

Greg Simmons: Over the last decade the market has been flooded with products based around low cost chip-based technology. Technically, these products meet all the measurable criteria for good sound quality, in terms of frequency response, noise, etc., but they often don’t have that magical quality that we call ‘the sound’. People ask, “Why should I pay $6000 for that, when I can buy one for $2000 which does the same thing?”

Rupert Neve: If it really does the same thing, then yes, buy the $2000 one. But the answer is often that it doesn’t really do the same thing, it only appears to do the same thing. The real answer to that question is that we have not yet perfected the means of measuring every parameter that contributes to sound quality. Even today, a manufacturer will quote total harmonic distortion figures without specifying the nature of that distortion. If it is second harmonic, it’s going to be inaudible and not something which will normally enter into the sound quality; period.1 If it is third harmonic and you get enough of it, particularly in the low end, it will start to sound muddy. It will modify certain musical instruments and the way they sound at the higher end. Anything above third is a total disaster and should not be present. You will find that in all these low-cost chip-based things, there is a wealth of high order harmonics present, mostly through crossover distortion and various other artefacts.

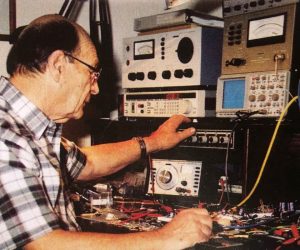

I have just purchased a new bunch of test gear. We were using it the other day to measure a new development I’ve got on the bench, and I found a fifth harmonic signal that was about 140dB down.2 It was below the noise floor. The nice thing about this new test equipment is that it can extract that signal from the noise. We zoomed it up until this tiny, weeny little spike – which was hardly visible on the scope in the ordinary way – was a large bar sticking up in the middle of the screen. On either side of it were two smaller bars, which were a kind of modulation effect produced by that fifth harmonic on the noise pattern it was embedded in.

GS: Like little sidebands?

RN: Exactly, they were sidebands. I was amazed, I never knew that before. I just knew that fifth harmonic distortion was undesirable; it was audible and you didn’t want it. But now we can quantify it, and now we can really strain at what we’re doing in the design stage to get rid of it.

Then there’s the seventh harmonic, which doesn’t appear in the musical scale at all. Any seventh harmonic distortion will sound pretty horrible, very harsh sounding, even at astronomically low levels. Any harmonic distortion higher than the fifth is bad. You know, I did some research with various people a few years ago, and came up with a curve of the audibility effects of odd and even order harmonics. You get to anything above seventh, and you can perceive the presence of that harmonic even way way below the noise level. Now, when we can get rid of all of those things, we’ve got the perfect amplifier. I haven’t designed any perfect amplifiers yet, but the people who base their designs on cheap chips have even less perfect amplifiers!

GS: You said before that if the distortion is second harmonic, it is going to be inaudible and won’t normally enter into the sound quality. Could you please explain why it is inaudible?

RN: Well, if you take a musical instrument and you determine that there is a second harmonic present, then yes, if you remove that second harmonic, that musical instrument will sound different. But if you vary the percentage of the second harmonic by some means or other, you change the timbre or quality of the instrument but it does not sound distorted and you’d have a hard job saying whether you had improved it or otherwise. In amplifiers, you can add second harmonic, but it’s got to be a huge amount…

Some years ago I produced a two-channel equaliser. In an effort to see whether we could make the signal sound warmer by the addition of a second harmonic, I put a second harmonic generator in it. People who were well known musicians and producers would call me and say, “Rupert, just between you and I, this second harmonic thing of yours doesn’t really work. There’s something wrong with it. Can I send the unit back and get you to fix it?” After a few questions, I would realise there was nothing wrong with the unit. They were adding in two or three percent of second harmonic, and saying they couldn’t hear the difference.

GS: Two or three percent of second harmonic was inaudible? That is a huge amount, especially considering that only a fraction of a percent of odd harmonic distortion is clearly audible in an amplifier.

RN: That’s right. Now, these levels of second harmonic were on a single channel. But when you put the two channels together in stereo, you can hear it. It changes the apparent attack, it changes the imaging, the whole perspective. The stereo picture starts to move forward and away from the speakers. Once you get it right, you don’t want to switch it off. But you’ve got to work it together on the two channels, I don’t know why, but that’s what you have to do. Then, when we had people who really wanted to hear the difference, we had to increase it to over five percent before they could actually hear the presence of that second harmonic.

GS: So some forms of harmonic distortion are obviously less objectionable than others. Assuming there will always be distortion in any audio circuit, as an equipment designer do you try to engineer that distortion into harmonics that are less objectionable?

RN: Yes, in effect. You choose devices, you evaluate the shape of the transfer characteristic and so on, and you can predict the nature and the order of the harmonics and the quantity of them. This is what makes one amplifier sound different from another. The ideal, of course, is to design all of your basic equipment, like your microphone preamps and line drivers and all that stuff, to be totally free of any kind of distortion, so they’d be theoretically perfect amplifiers. And then have boxes in the middle that are not perfect, but they are not perfect because you have made them so, and they are effects units.

GS: All this talk about second harmonic generators was in reference to an equaliser you designed some years ago. Your equalisation circuits have always been very popular with sound engineers. The documentation for AMEK’s System 9098 EQ refers to the famous Rupert Neve EQ curves, and there are some quotes from yourself saying it is very similar to curves you developed years ago. What sort of shapes are we hearing?

RN: It is a very powerful EQ because the steepness of the curve slopes are equal to or exceeding 6dB per octave. If you compare that with a curve that is only 3dB or 4dB per octave, which most of the ordinary type of EQs will give you, the steep sided curve changes the nature of the instruments. At 6dB per octave, if you are doing something around the fundamental frequency of your acoustical instrument, then you are obviously changing the relationship with the second harmonic, and, of course, the third, and so on. If the curve is very gentle, you are still changing it, but not as much. It is really subjectively tied into this thing I was talking about earlier, the ringing effect due to equalisation – with a lot of boosting at given frequencies, resonance occurs, and so on.3 You are changing the relationships of the harmonics, you are changing the phase, and it’s a different sound. So you use it for different purposes. I have also included the Sheen and the Glow functions, which are much gentler curves. They are just 3dB or 4dB per octave curves which will give you, in the low end, a warming effect, which I call Glow. Sheen works at the high end; it will lift or cut a whole range of high frequencies, and enable you to sweeten the sound without changing the nature of the instruments. In comparison, the steep sided curves will change the nature of the instruments.

GS: These curves are available in shelving and peak/dip situations?

RN: Yes, it comes back to what you are trying to achieve. If you’re using a high frequency peak/dip curve, once you hit the maximum amplitude, it will roll away, which is good if you just want to lift a small band of frequencies. You may want to make your strings sound a little bit, well, I don’t know how to describe it, a little bit ‘fiercer’, if you like. Yes, it’s not even ‘edge’, so much; it’s kind of like, ‘chromium plated strings’. You could use a peaking EQ curve to get that sound.

But if you use the shelf characteristic, then you lift the whole of the harmonic content by the same amount. Now you have got, not the ‘chromium plated strings’ effect, but a stronger, brighter sound. Again, it’s a matter of the tool you use to get your different sonic effects.

GS: You’ve incorporated a microphone preamp in the System 9098 EQ module, making it like a rack- mounting channel in some respects. Is this the same preamp circuitry found in the Dual Microphone Preamplifier and the RCMA?

RN: All the microphone preamps are the same, but on the RCMA the output circuit is different. Each channel is a distribution amplifier that gives you three totally isolated outputs. You can switch them to produce one output, or three outputs at a lower level. The three outputs are three separate windings on the output transformer, so you can use them in the usual kind of remote broadcast situations. You can throw a line to the house PA and he can trample it under foot, or short it out, or do whatever he likes to it and it won’t affect your main signal.

GS: All your preamps have a switched gain going in 6dB steps, plus a continuously variable ±6db fine control. What is the philosophy behind that?

RN: Oh, just accuracy. Going back to the dawn of time when I started doing these things, we were competing with German companies like EMT and Neumann, and with EMI, and old timer engineers who came out of the valve era. Everything was done with big chunky switches and transformers. Continuously variable volume controls, or potentiometers, were very poor quality in those days. No professional would dream of using such a device. So it was always a switched attenuator.

Depending on the application, you had a rotary switch that might have 54 steps, or ‘studs’, on it, and a fixed ladder attenuator. That was the way to do it. The potentiometers didn’t exist with the required accuracy or low noise. The other thing is, when you are changing the gain in a feedback circuit, what you actually require is a potentiometer with a reverse log law. In those days you couldn’t even get a linear potentiometer that was any good, let alone a reverse log one!

Most of the cheaper consoles use a potentiometer for gain control, and you cannot accurately set the difference between, shall we say, 45dB and 50dB gain. You’re trying to set up a bunch of channels so they all give you the same gain and it is virtually impossible. But with the good old switch – you don’t even need to look at the calibration on the channel, you know that when you reach that click position, it is the 50dB point. You are going to get them all the same if you want them the same. On the 9098 products, they are within a third of a dB of each other.

GS: And then you have the ±6dB fine tuning…

RN: Yes. That is simply a bit of luxury. I have seen broadcasters use that if the signal gets a bit hot. To avoid overloading anything, you can back it down seamlessly using both the switch and the pot. You have got the continuous control in one hand and the switch in the other hand. You chose the right moment with the words or music, and you can start to inch it down and nobody would ever know you’ve done it. You have the opportunity to ride the gain if you need to, without using a fader.

GS: The System 9098 EQ features a ‘double balanced microphone amplifier’. What does that mean?

RN: It is a technique that has been used for a number of years, in all kinds of equipment. The double balanced amplifier is where you can gain a 3dB improvement in noise by using a balanced signal as opposed to an unbalanced signal.

The 9098 EQ has a balanced line input and a microphone input. When you switch the microphone preamp in, you are actually internally connecting the output of the microphone preamplifier to the line input. The first thing I wanted to do was to feed that line input as a balanced input should be fed: differentially. So I simply gave the mic preamp a differential output. It is not a transformer like output, it’s not intended to feed the outside world, but it is intended to feed the balanced line input of the equaliser.

Due to the differential output, you have a 6dB increase in signal level. Each leg is producing the same voltage, so you’re doubling your voltage output, which is a 6dB increase. But the noise, which isn’t coherent and is random, is only increased by 3dB. So you have actually got a 3dB improvement in the signal to noise ratio. That is pedantic, if you like, but I think it is quite worth having.

The other advantage is that you can simply put in a switch that crosses over the two input legs of the balanced line input, and you’ve got a phase reverse switch without having to go through an additional inverting stage. And because the phase reverse is located on the line input, it works on both line and microphone signals. We assume that it is going to be fed balanced, although you can use it unbalanced if you want. But the trouble with a TLA4 type of input is that if you feed it unbalanced, you are grounding one side, and now you are limited to the clipping point of one amplifier. You have thrown away 6dB of level and you’re limited by the rail voltage that you’ve got.

A number of people have used double balanced inputs. It’s not original, it’s generally a good thing to do.

GS: Moving on to the System 9098 Dual Compressor/Limiter, I noticed it has digital control circuitry. How did that come about?

RN: Originally, we started to produce something which was similar in concept to the old Neve limiter compressors, the 2254s and their successors. The trouble with all that old stuff is that it sounds very sweet and very musical, until you get tired of it… It creates a certain effect, and some people like that effect. But my argument for the new stuff is that the old stuff was created 30 years ago, and you don’t want to be stuck with an effect you can’t get rid of. You can, however, create that effect with the new equipment. So you buy the new equipment, and you get the freedom to do it any way you like.

The actual control ratio curves are quite difficult to do in analogue terms. What we did all of those years ago was OK for the history books, but it is not accurate enough for present day applications so far as repeatability and accuracy, calibration, and so on are concerned. In analogue terms, it was quite difficult to do. I reached a point where I had just about done it, and I knew that it was better than the old one, but I wasn’t entirely happy, because I knew it ought to be better than that. So I talked to Graham Langley at AMEK, and the AMEK boys – with their experience of Virtual Dynamics5 – developed the digital control for this compressor. We now have an extremely accurate compressor, but with the original sonic qualities, because of the analogue audio circuitry. It’s very accurate.

GS: How is your working relationship with AMEK?

RN: Oh, excellent. When I joined them in 1989, Nick Franks told me that they really wanted to introduce a lot of high end products and move the whole thing upmarket, which I believe they have done quite well. So I said, “What exactly do you want me to do?” and he said, “Just have fun, you have carte blanche, do what you like.” As a designer, you can’t ask for more than that! It has been very good. Graham Langley is a wonderful designer, and he and I complement each other a great deal. So we get on well together.

GS: In your opinion, how does a 9098 console stand in the history of other consoles you have designed?

RN: We wouldn’t have released it if we didn’t think it would be a quantum step forward compared with stuff I had done in the past. It stands with the golden oldies, the 8078, the 8056s, the 8068s and so on. Those very favourite classic consoles that are still circulating today – much to my chagrin!

The new stuff is so much more accurate, and yet the sonic quality is nice and it’s much better than the old ones. If you like, you can set it to reproduce the same sonic quality as the old ones. The new stuff will last longer than me, because some of my old stuff – which is 30 years old or more – is still in use today.

GS: You said some of those older consoles are still circulating today, “…much to my chagrin!” Why does that annoy you? Surely you’re proud to know that consoles you made 30 years ago are still in demand?

RN: Well, you can’t eat pride! I still have to put bread and butter on the table. The problem with the old ones is that they won’t go away. When I sold a new mixer in the old days, I might have made some money if the accountants had gone and got the numbers right, and we charged the right price. But when it’s sold as a second hand unit, I don’t make money on it, and when it’s sold as a fourth or fifth hand unit, I certainly don’t make anything! Yet I still get calls all the time from people who ask about these old ones, whether they can get spare parts, and so on.

Personally, in some ways, I could go so far as to say I’d just like to see the whole lot lie down and die! And I’d sell a whole bunch of new things. That’s good for the customer, too, because they get a better product.

New things should not be more complex. A virtue of the old designs was that they were simple: no automation, no computer screens, no ‘virtual’ anything. I’d like to design consoles like that again, with the same tradition of sound quality, but with the improved performance and reliability we can get with modern components.

In the next 12 months, there will be new products that will be direct replacements for the old ones. We will be looking at consoles in that price class with that performance. Very simple consoles without automation, just like the old ones, but obviously much more reliable, and so on. Same tradition of sound.

GS: It seems you suffer from the legacy of making something decent in the past…

RN: Well, if you compare it with present day thought, everybody is computer minded these days. You buy a computer and, before you’ve got it home and set it up, it’s out of date. A few years ago, the CBC people in Canada said, “Give us one reason why we should buy one of your analogue consoles, and not a digital console”. So I drew the same parallel with the computer. Of course, we know that digital consoles are never right. You get your digital console, set it up in the studio, and the first thing you do is decide which of the many update disks – that have been arriving in the post over the last few weeks – you are going to use. You know, the fix is in the disk! It is out of date before you start. Everything in digital is programmed, which means you have to visualise everything and then it’s done in steps, very accurately but unforgivingly – if you’ve forgotten something or not given it sufficient importance you have to start again. Analogue is infinite.

The thing about the digital standards is that they are going to change, and I wouldn’t want to be saddled with a piece of equipment which is genuinely going to be obsoleted. Analogue will never be obsoleted. Although, having said that, digital will be very very good within the next few years. Within five years, you will have digital so good, you won’t be able to tell the difference between the best analogue and this particular form of digital. It will still be more expensive, but of course it will be more powerful, too.

GS: On that forward-looking note, can I ask you for a closing statement or, perhaps, a philosophical comment about equipment design?

RN: One must do the best one can. Philosophically, people need to keep in mind why they do what they do. We are all creative people, but very few are in the fortunate position that we are – in music, recording and professional audio – where we have the actual opportunity of exercising our creative talent. Huge numbers of people around the world don’t have this opportunity. The vast majority actually spend most of their energy and resources looking for their next meal, trying to feed their family, keeping a roof over their heads, desperately worried about the future. Ambition has just been sucked out of them. But you have the same spread of intelligence, the same spread of creativity, because we are all created by the same creator who, as a creator, created man in his own image. Therefore we are, ourselves, kind of mini creators. That in itself gives us a huge sense of satisfaction.

I just like to remind people that we are very, very privileged in our industry. We can do things that we enjoy doing. We should not forget the millions around the world who do not have that opportunity. What we do about it can be reflected in the program material we produce. Is there something about that which is in any way going to benefit mankind? It sounds very high flying to say these things, but I think it is important that we contribute positive values to humanity, and not negative ones. Not dragging it down into things that glorify the drugs, the violence, and so on. It has all been said before, and I don’t put it as well as other people do. But we are in a privileged position. As a designer, I simply do the best that I can, the best that my creator enabled me to do, and then hand it on to you guys, your readers, and say, “now it is up to you to do something really positive with this beautiful piece of equipment”. I know that’s a very arrogant statement to end on, but…

GS: I think that’s a profound and beautiful statement to end on, Rupert. Thank you very much for giving us the time required for this interview, it’s been a pleasure and a privilege.

RN: Well, I’m sure by the time you sort it all out, you’ll be fed up with me! [Laughs]

1 This statement is qualified later in the interview.

2 140dB down is equivalent to 0.00001 percent!

3 Refer to Part One of this interview.

4 TLA stands for ʻTransformer Like Amplifierʼ, a solid state circuit designed by Rupert Neve to mimic an input transformer while avoiding many of the inherent problems of input transformers. TLAs are used extensively in AMEKʼs System 9098 series, and were explained in detail in Part Two of this interview.

5 Virtual Dynamics is an AMEK development that uses digital control of a consoleʼs VCA faders to apply dynamic processing to a signal.

What a fabulous interview Greg Simmons! Rupert was certainly flying through the ether with his technical comments and the subject of Jeff Emerick and the digital switching noise way up in the High freqs and its possible effect on human psyche was very interesting. Thank you. Great stuff!