Last Word with KC Porter, Part 2

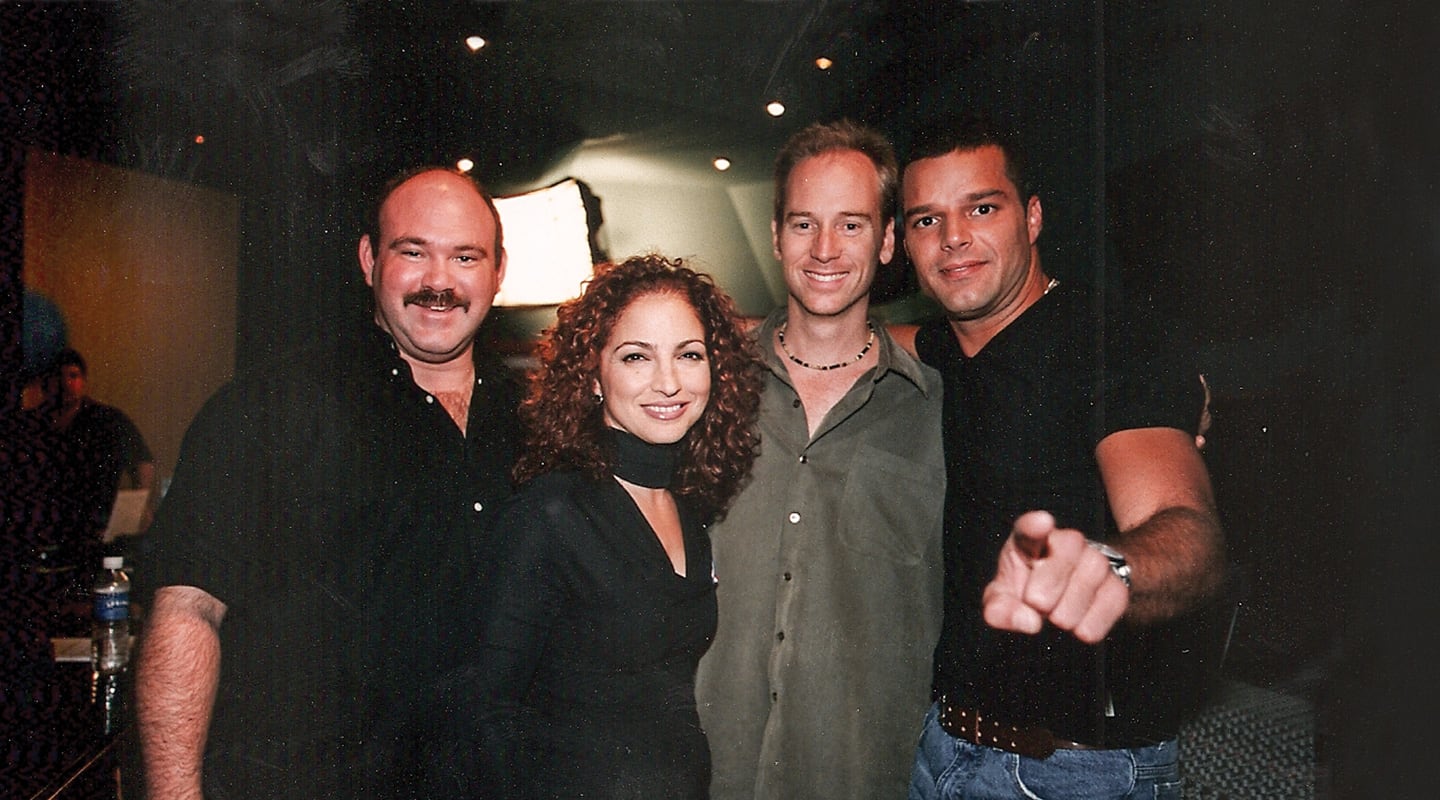

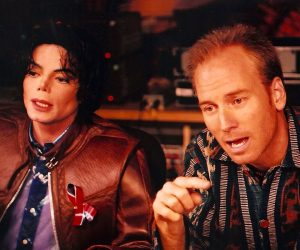

KC Porter is a multi Grammy-winning producer who made a name for himself producing Ricky Martin. He has worked on Spanish language versions for hit artists like Michael Jackson, Boyz II Men, and Toni Braxton. He also produced Carlos Santana’s Supernatural. We’ll cover Ricky and Santana next issue.

JMC Academy recently brought multi Grammy-winning producer KC Porter out to Australia on a masterclass tour. This issue we look at how he transformed Ricky Martin from a career in boy bands and the theatre to a global superstar. As well as finding a spiritual connection with Carlos Santana to capture that storied guitar sound. For more information on JMC’s Audio Engineering & Sound Production Course, go to www.jmcacademy.edu.au

I was producing this one well-known artist in Puerto Rico, and her manager also managed Ricky Martin. He said, ‘I’d like you to work with this guy.’

I was reluctant at first because Ricky came from a boy band and I considered myself to be more of a producer of real, lead singers. Ricky is more of a package artist. He’s a great performer. He has amazing stage presence, is a great dancer, and is a great interpreter of music — he can bare his soul musically — but I wasn’t so much about performers as I was singers like Toni Braxton or Boyz II Men, Chaka Kahn or Brian McKnight. I get frustrated too, producing singers that aren’t really singers, it’s a lot of work.

Working with Ricky was a wonderful experience. We were able to do whatever we wanted. The label didn’t get it, they wanted him to be the next Julio Iglesias. They thought he was a crooner in the making. The breakout single was Maria, which the label didn’t even want on the record. I left it on the record anyway, and the rest is history.

Ricky was very busy at the time, we’d always get artists after a tour when they’re exhausted. They were pulling him everywhere — he was in a soap opera and had just done Les Miserables on Broadway. We had to boost his energy and take out the Ethel Merman factor that happens on Broadway; make him a cooler, smokey, rock/pop guy. It was a challenge to take some of the bubblegum out of his image.

Santana was the next project. He told us that when he was praying about the album the message he’d received was that he needed to step back and trust in his producers. He had been burned so many times by trusting bad producers and management. He’d taken control of his career, but when he met Clive Davis he decided to let Clive and myself take control. Our side was about honouring Carlos’ vibe. We had a great working relationship and connected on a spiritual level.

A friend of mine and guitar player, J. B. Eckl, was a hardcore Santana fan. When they asked me to meet Santana in the studio, I called J. B. down. The first thing Carlos does is pull out all these posters of paintings. We’re looking at all the colourful, crazy paintings and he said, ‘that’s what I want my music to sound like.’ We were realising that Carlos wasn’t your average artist. He was living, breathing and speaking on a different frequency. If we wanted to honour what he was looking for we had to get on that frequency. He would say something like, ‘we need to connect the molecules and the light.’ He would use a lot of terminology like that and we’d panic. Then we’d figure he was trying to bring some light into the darkness, or combine the material and the spiritual. He didn’t ask whether things could be pink or purple until about the third album down the way. Then he said, ‘it feels a little blue, could you make it a little more red?’ I looked at

J. B. — ‘it had to come!’

He would put his thumb in front of his face, with his pinkie pointing away so you don’t see the palm of his hand. Then he’d line his right hand up behind it so you could barely see that either. He would say, ‘my guitar sounds like this right now, and I want it to sound like this.’ Then he would fan his hands open so you could see the palms and fingers. He wanted his guitar to sound fuller, warmer, bigger. He didn’t want it to sound transistory, or thin. It’s all about the size of the sound. Carlos was very pleased with what we were doing, but it took some trial and error.

At the end of the day, recording his guitar boiled down to capturing not just the speaker, but the phenomenon produced in the room. Carlos would walk out into the tracking room and hear his guitar cranked. Then he’d go back into the control room where it was coming out of the big speakers, but it wouldn’t give that same effect. We needed to figure out how to capture the balance of the speaker and room with the right preamps.

We probably used an SM57, we weren’t using ribbon mics. We’d move things around, and try to work out the best positioning for the amp. The speaker we used was a little Boogie cab. It wasn’t a massive 4 x 12 cabinet. The Dumble amp was also the magic. I wish it was easier to get a Dumble amp, but they’re very cost prohibitive. We ended up using the class AB Neve 1081s, which is not the same as class A, but they were beautiful.

That signal chain we landed on at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley was magic. It ended up being where he would record from that point on. People would say the tones we were getting on his guitar were the best they’d ever heard from him.

I had a Neve 8036 in my studio, and everything was done in analogue. It was the last thing I did completely in analogue on 499 Ampex tape, and a Studer A37. There was nothing like the sound of that Neve, I wish I could still have it, but it’s just not practical. If you listen to Primevera it’s indicative of a mix on that console. It sounds smoother than smooth. Every time we’d see Carlos after the album came out, he’d just look at us and say, ‘Primavera!’’

RESPONSES