Band In A Bubble

Few failed to notice Regurgitator’s antics during the recording of their recent album ‘Mish Mash’. To some, recording in ‘the bubble’ seemed like a very thinly disguised publicity stunt, while others just wished they’d thought of it first. Mark O’Connor discovers what it was like for Regurgitator’s cast and crew behind all that perspex and glass.

For any other band it would constitute a radical step. Let’s see… 21 days inside a purpose-built glass bubble… On public display the whole time in the middle of Melbourne’s Federation Square… Under 24-hour Big Brother-style television surveillance every step of the way… For what? For the express purpose of engaging in the creative process?! As I say: for any other band that’s pretty radical. There again, Regurgitator are well used to existing in the outer edge of the pop envelope and ploughing their own furrow. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that it almost seems like a natural progression.

Of course, to make a record you need more than a band. So it was that long-time ‘Gurg’ producer Magoo and assistant engineer Hugh Webb also packed their sleeping bags. And, for this ‘happening’ to work for television you need a ‘cable guy’ – enter manic Channel V presenter Jabba along with a slew of television cameras to record the band’s every move and moment.

Regurgitator then proceeded to make its fifth album Mish Mash. In the process they turned reality television culture on its head and pushed the boundaries of the record-making process as we know it.

I spoke with some of the lead actors in this mad movie, beginning with producer, Magoo, to learn more about life and the creative process inside the bubble.

RECORDING IN A BUBBLE

Mark O’Connor: This is the fourth album you’ve made with Regurgitator. How did the experience and process of making this record differ from those other albums?

Magoo: It was very tiring for one thing, which did get to me. As soon as you woke up there were people outside watching you eat your cereal – you always felt like you were on show, so you were constantly on your toes. I was very much aware of the band feeling the pressure to always be performing, to always be doing something. And my philosophy was, “Well, of course performance is a part of making a record, but not every minute you’re in the studio”. I was always trying to push the fact that people want to see how a record is made – which was, after all, the premise of this whole thing – and part of that involves a lot of sitting around and waiting for something to happen. Also we don’t usually record over such a short and intense period. We did the whole record in 21 days – usually you might do a week or two and have a bit of time off, and then come back with a couple of different songs or a different stylistic approach to one or two of them. That didn’t really happen that much this time. Ironically I don’t think we got as experimental as we usually do.

Mark O’Connor: To what extent did the television component encroach on the record-making process? Was it a distraction?

Magoo: The television aspect was very distracting, but it didn’t take long before we got into a pattern. We’d basically wake up, there’d be a few interviews, we’d do a couple of hours work, Jabba would do his crosses, we’d do another couple of hours work, then there’d be the half-hour show. Everyone just got used to it after a while: “Right, we’re playing… no… we’re not.”

Mark O’Connor: There’s a delightful sense of controlled chaos to the album. Is that intentional, or just a spilling over from what I imagine must have been an often chaotic time in the bubble?

Magoo: Yeah, it is a chaotic album, which is good. I definitely like recordings to have a lot of life in them. I’m by no means a perfectionist. I love the whole concept of songs and where they can take you first and foremost, more than I do the little intricacies of the bass drum tone or how you double-tracked or triple-tracked the guitar part. I’m much more concerned with the overall picture.

Mark O’Connor: So you’re not one to necessarily spend hours finessing a sound?

Magoo: No, although I’ll definitely have a picture in my mind of how I want it to sound. If I want the drums to be really dead in a song then I’ll make sure they’re all in tune and deaden them up with as many baffles as I can fit around them. Conversely, if I’m trashing something up, I like to keep it open – I’ll usually have one or two mics around the drumkit that are trashed up rather than adding that distortion in mixdown. I’d rather have those couple of mics there doing that job, with the close mics there for clarity if you need it. So it’s organised chaos, I guess. It depends on the song. But I don’t finesse things too much – I like to leave a bit of room for it to go somewhere else you may not expect. And I do like changing things quite a lot in the mix. Thankfully, we mixed the record at Studios 301 in Sydney – I think mixing it in the bubble would have been quite disastrous.

Mark O’Connor: Notwithstanding the obvious presence of technology on this record, Mish Mash still sounds essentially like a three-piece band to me – drums, bass and guitar.

Magoo: Definitely, probably more so than any other record I’ve done with Regurgitator. In the early days they were always playing with samplers and embracing technology. And I think as time has gone on, and especially since Quan came back from overseas, the live shows have just improved so much. I think from that they’ve acquired a new respect for simplicity.

THE SETUP

Mark O’Connor: Can you tell us a little about recording the band, from pre-production to the actual tracking in the bubble?

Magoo: The songs were all written beforehand. Quan, Ben and Pete are all quite accomplished at recording themselves. Quan and Ben both have their own ProTools rigs and they’d demoed all the songs and tried different ideas. We only had one very small pre-production meeting with me hearing the songs and airing my thoughts on them, and discussing what we were going to try and do.

In terms of recording the band, I DI’d the bass and miked up the cabinet – we had a ‘fridge’ in there: an Ampeg 8×10 and an Ampeg head. I actually prefer the ‘minibar’, the 4×10, which we tried to get, but Ben decided on the fridge.

For guitar we used an Orange amp: a 30W head and quad-box, which sounded beautiful – I fell in love with the head and have since bought it for myself – and Quan’s got an old 50W Marshall. When we were doing bed tracks I started off miking up the guitar amp, but the little room where we had the guitar amps had perspex walls, which wasn’t great for isolation, so I ended up using the [Line6] Pod usually for live takes, and then more often than not we’d overdub the guitar.

One of the big things with Black Box [Magoo’s mobile studio setup] is we collect guitar pedals, so we took in as many as I thought we might use.

The Rode Classic was our main vocal mic, and set up next to it in the vocal booth was a little lipstick camera, and there were nine plasma screens on the back wall for watching the vocal overdubs. Sometimes Channel V put Quan up on the big screen in Fed Square during vocal takes, and there were screens outside the bubble and a PA, so people outside could hear everything. Often there was a crowd of people watching and when he finished a take you could hear them cheer. You didn’t really have to think too hard about whether it was a good take or not, because you could just hear the crowd after it was done. That aspect of the process was quite amazing.

Mark O’Connor: As well as the music emanating from inside the bubble to the outside world, you were also able to record from the outside in – for example, you recorded french horn and tuba on My Ego.

Magoo: Yes, we had two mic leads running outside and a headphone extension. I spent ages trying to get that to sound like a tuba – being outside on the corner of Flinders and Swanston streets on the weekend, with trams and all sorts of things going by. Shoving a [Sennheiser] MD 421 down it didn’t really do it justice. You try and filter out the background noise as much as you can, and the rest you just live with…

That was a great part of the bubble actually, that whole thing of having all sorts of people come by and play. For example, at the beginning of I Was Sent By God there’s a strange instrument called a Hang; which is something like a steel drum inasmuch as you hit it in different spots to produce different notes. This guy outside had it as we were trying to get the bed down to God, and he was like, “Oh, I’ve got this thing here, this little melody, it kind of sounds like it’s in tune,” and we heard it and thought, “That’s interesting”. So we recorded it and it sounded fantastic. It ended up opening the song.

Mark O’Connor: You also had Eskimo Joe sing backing vocals on Sensible.

Magoo: They had one go at it while the show was on air. I found two bars that were in tune and whacked it in! [laughs] There was lots of that – you’d just capture a little bit and that’d be enough.

I think mixing it in the bubble would have been quite disastrous.

HUGH WEBB – BLOWING THE BUBBLE

Ostensibly the assistant engineer in the bubble, Hugh Webb, made himself indispensable by performing a number of roles: “…basically assisting with mic placement, patch guy, guitar tech, toast and cup of tea maker, washer boy…”, not to mention serving as occasional camera wielder for Channel V’s television coverage.

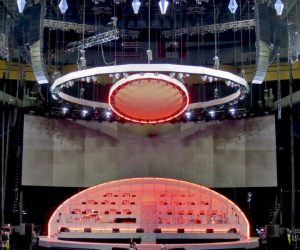

Hugh Webb: To start with, Magoo, myself, and Jeff Lovejoy (Magoo’s business partner) packed up the Black Box into a big van in Brisbane and headed down to Melbourne. Once we unloaded, everything was built relatively quickly. It was a matter of working out what outboard gear had to be set up and then spacing it all out, finding out which way the space could be utilised and manipulated to our best advantage. It was a case of, “Okay, bunk-beds? They’re gonna end up as some kind of acoustic baffling in that corner there. The couch? That’ll go in front of those plasma screens and hopefully absorb a bit of stuff and help with early reflections.”

My biggest concern was to run the cabling super-neatly so that we could work in a really comfortable area without walking over spaghetti everywhere. With six people living in a small space you can’t afford to have 55 metres of excess cable for one mic lead.

The next step was to acoustically treat the room. We put up a whole bunch of acoustic tiles that were supplied for the project. For the past three years I’ve worked as an audio guy on Big Brother, which involved lots of acoustic baffling to try and get rid of horrible nodes out of rooms. It wasn’t so much sitting down with a computer and working it out as it was standing and hanging a piece of acoustic tiling and going, “How does that sound there? Maybe take it back a foot and a half and angle it down slightly…”, to take out any big bottom end lumps in the room.

Mark O’Connor: Once you’d achieved that, did it remain static for the duration, or did you find yourself moving stuff around during the course of the recording?

Hugh Webb: The control room was pretty much set-and-forget. But as far as the studio was concerned, we were moving stuff all the time because it was such a confined space, and it was important to try and maximise the amount of flexibility in the room, not only for acoustic purposes but for sanity as well. There was no place in the bubble where you could walk any more than 6.5 paces in a straight line – I worked it all out; when you’re going a bit nuts you try and find interesting things to do. So we tried to be as conservative with space as possible – we had baffles that we were constantly setting up and putting away. Basically, it was a case of build and re-build every day. Things were forever changing.

Mark O’Connor: There was some interaction between the bubble and outside world, in so far as you had the facility to record musicians playing from outside the bubble. How did that work?

Hugh Webb: We basically had the facility to record from either mic or DI. Because we weren’t allowed outside, we’d give a microphone to the site manager with placement instructions, and communicate with the musician through the intercom and headphones. At one stage Ben wanted a heavy metal guitar solo on Shopping Mall Soul so they ran a competition on Channel V and got four or five guys down, dropped a DI out there, put them through AmpFarm and off they went. The band ended up comp’ing four of the solos together to make one crazy solo. There was also a Sennheiser 416 shotgun mic suspended in the roof outside the bubble so we could capture ambience at any time; from drunken idiots to people singing. Sometimes we just miked up the intercom, recorded it on MiniDisc and then cut it up later for banter segments between songs.

Mark O’Connor: Assisting can be a thankless task, but 21 days straight?

Hugh Webb: I don’t think I can compare it to any other studio situation. It was very weird, but also amazing at the same time. There were moments where it got quite insane, but I mean we were living inside a 9.5 x 6.5 glass box under 48 fluorescent tubes – with 48 fluoro tubes on all day, you start to go a bit grey. It was a bit like being inside a 7-Eleven laboratory.

POST-BUBBLE-ISM

I spoke finally with Regurgitator’s Quan Yeomans about working with Magoo, about the beauty of transparency, and the pros and cons of a live gig that lasts three weeks.

Mark O’Connor: Was the decision to make the record this way a deliberate attempt to push your own envelope and to challenge yourselves artistically as much as it was a publicity stunt?

Quan Yeomans: It was both. This is our first independent record ever, so I was basically thinking, “How the f**k can we do this?”, in terms of distributing a record without having the promotion that’s involved and the money behind you etc. Times have changed in terms of marketing and getting your message out there. You’ve got to work out interesting new ways to do it, and keep on challenging yourself on a personal level as well as an artist. So far it’s debatable whether the marketing aspect has helped album sales at all. Had we had commercial television saturation I think it would have been a different thing – much more like a publicity stunt and a novelty. But because we were broadcasting through a cable channel, which is a bit less mainstream, I think it retained its integrity as an artistic idea and expression. As it was, I was terrified because of the corporate element and the sponsorship – I was unsure how it would look to people on the outside. But I think it was fairly transparent, no pun intended. That was one of the nicest metaphors about the thing: transparency of process, transparency of personality – I think that was a key element to it. We were really insistent that it be as natural (and boring a lot of the time) a view of what it’s like for a band to record as possible.

Mark O’Connor: How did the experience of being constantly under scrutiny affect the recording process? Did it dilute your focus?

Quan Yeomans: No, if anything it enhanced it. If our focus was scattered it was probably more by the media than anything else. Having to do a half hour live TV cross every day, plus interviews and sometimes a morning breakfast show – that was distracting. The public were a pleasant relief by comparison. But the TV element was a priority and I think that was fair enough.

Mark O’Connor: Did you experience some self-consciousness in terms of the trial and error aspect of the creative process?

Quan Yeomans: Oh God, yeah. When you’re doing vocal takes you’re self-conscious enough. I’m a very average singer, so it’s terrifying when you’re doing it like this. Being up on screen the whole time in front of lots of people, you’re vulnerable. I think it’s about confidence. If you have something to say, then go for it – that’s the only motivation I have really. And the bubble pushed our confidence levels to the limit.

Mark O’Connor: In what other ways did being in the bubble change the way you went about making a record?

Quan Yeomans: Our time management methodology changed – the way we worked, the amount we worked and how fast we worked. There was a heightened sense of performance because we were being watched all the time. There was a stage-like quality to it all because of the cameras and the people around you, so you’re pushing yourself harder and getting a lot more done in the time you have because you feel like you should be entertaining people. That’s what burnt Jabba out so quickly – it’s his job to entertain people on TV, so theoretically he was on 24 hours a day. For us, as a band as well, it felt like we were playing one very long live show. The adrenaline rush was the same. When you get up on stage in front of people, no matter how many or how few, it’s kind of exhilarating. In the bubble it was 24 hours a day. You’ve got this heightened sense the whole time, and it comes out in the performance. The playing itself is of a reasonably high quality but has an edge to it like a live concert.

You didn’t really have to think too hard about whether it was a good take or not, because you could just hear the crowd after it was done.

20/20 VISION WITH MAGOO

Mark O’Connor: Can you describe your working relationship with Magoo? What’s his role as you see it?

Quan Yeomans: We usually come to him with these fairly well structured demos, which we’ve often become quite attached to – and in that respect I think it’s sometimes quite hard for him as a producer. But Magoo just says what he thinks; he’s a musical second opinion outside the band. And he’s willing to take risks with sound and do stupid things to see how they’ll turn out, which is what he’s built his sonic sense out of – playing with sounds and having a non-precious attitude towards altering sound and sound-making.

Although, on this album, I think a part of Magoo was pissed off he didn’t have more time, particularly in the mixing. We only gave him 10 days, and his brain was completely fried from the 21 days in the bubble, with only something like three days off in between. So he really worked hard. He’s one of those incredibly stoic personalities, easy-going, and very experienced with what he does.

THOUGHT BUBBLE

Mark O’Connor: Was there perhaps, somewhere in this exercise, an element of subverting the whole voyeuristic culture of reality television and multimedia?

Quan Yeomans: There was certainly that intention there, but it really had a life of its own. As it grew we started realising what a crazy animal it was. You’d have these mad cross-media type things with feedback loops occurring…

Mark O’Connor: How do you mean?

Quan Yeomans: Magoo might be scratching his beard – and then he would catch himself doing it on the giant screen 300 metres away in Fed Square. Or we’d be conducting web chats with kids and they’d be listening to us on their TVs and typing back responses to what we were saying; or doing interviews with various media people outside the bubble and seeing their faces change when they realise it’s all being captured live.

But as I said before, I really liked the metaphor of the transparency of the project itself. It’s something that’s missing in this democracy we live in. That’s the reason why so much corruption and exploitation occurs in the capitalist system, because of this lack of transparency in the corporate world, the political world, the economic world. Although all media is propaganda, there’s no way you can get around it – there’s still somebody in control of these cameras, there are still editing processes occurring and they’re actually dictating what’s being broadcast. The only true reality TV out there would be miniature TV cameras on a person without their knowledge recording 24 hours a day. What we have now is a very preconceived, surreal version of reality.

So I think there was something subversive about it in nature. I think that was evident in the people that approached the bubble, particularly friends that came down – just their level of awkwardness. Or having ‘stare-outs’ with complete strangers, having these kind of ephemeral connections – intimate connections – with just the glass between you. It was very strange. But I’m really happy with the experience. I think what we did was a world first, and a heightened way of living. I’m happy with the record itself too, although I don’t think it possesses the outstanding artistic merit of the actual experience itself. There are some good songs on there; it flows in a quirky manner, which is typical of our style. I think it’ll be interesting to see what our music is like now that we’ve gone through this experience.

RESPONSES