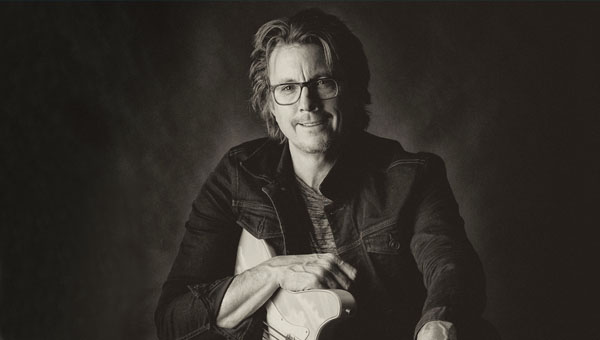

Last Word with Paul Petersen

with Paul Petersen

Paul Petersen was discovered at 17 by Prince, and hand picked to appear in his 1984 Grammy-winning film Purple Rain as the new keys player (replacing Jimmy Jam) in the funk group The Time. Dubbed ‘St Paul’ by Prince, Petersen fronted follow-up Prince project, The Family. Petersen released two solo St Paul albums and has produced, written and appeared on countless others. Hit him up on www.paulpeterson.com

I grew up in Minneapolis in a musical family. My Mum and Dad were great session musicians of their time. My Mum played all the way up until the day she died, aged 92 — she was a renowned jazz keys player. My brothers and sisters all played for a living.

There were always instruments left around the house. We all played something different except me, being the youngest, I’d grab them all.

I remember as a 16-year old approaching my Mum to tell her that Patty (my oldest sister) wanted me to play six nights a week in her band. Her response: “as long as you can get your homework done that’s fine”.

I was playing bass at that time and word got around that there was this young player out there making a name for himself. Right after graduating from high school I got a call from my brother telling me I had an audition with Prince’s project, The Time. Terry Lewis and Jimmy Jam had departed and my name was put forward to audition for the keys part.

I got the gig, and at rehearsals we had all the equipment we needed. I had an Oberheim OB8 and a Yamaha CP70 (electro mechanical piano) to play.

There I was, age 17, stepping/dancing, singing and playing, learning about the technology of the day, production, branding and marketing. It was an amazing education.

After The Time broke up Prince formed a new band called The Family and he appointed me as the lead singer. Prince produced the album and wrote the songs. At the time he produced just about all the synth parts on a new device called the Yamaha DX7! Dude found a way to make that synth sexy, cool and funky at the same time. He took those new FM sounds and combined them with the funk backbone of live bass, guitar and drums and, in the case of The Family album, a live orchestra.

After recording The Family album we performed one live show at First Avenue, Minneapolis. We rehearsed for nine months solid, six days a week. Then the band broke up.

Prince was a great producer. First of all he had great songs to work with — he knew how to write hits. A lot of people can’t produce their own music, Prince wasn’t one of those guys. He really thrived producing himself.

He was a great inspiration for us at that time. The feeling was: if Prince can do it himself, then I can too. There was friendly competition among us as would-be producers at the time. Our ears were opened. We were listening to all aspects of production: parts, sounds, the mix, effects, EQ, reverb, gated reverbs back in the day — all of this was on our minds.

As an artist in the early ’80s you wouldn’t normally soak up all this info, you’d just play, but I think it was his influence that showed me I could do this myself. Most music business people back then would say, ‘kid you don’t know what you’re doing, let’s get an experienced guy in there’, but Prince gave us the license to demand this kinda freedom from major labels from such a young age.

Saying that, it wasn’t like Prince was actively encouraging us. Artistic license? Hell, no! Working with Prince he just wanted you to do as you were told — if everyone plays their part then there’s a beautiful blend — he had that big-picture vision.

My early days of embarking on a solo career and being a producer involved a very steep learning curve.

It was about that time, 1985-86, that the first sequencers came out and the Yamaha TX816 monster FM rackmount synth — the refrigerator, as we called it.

After leaving the Prince stable I needed to come up with a demo tape for MCA Records. Their attitude was, ‘great, we’ll sign you but if you want to produce your own records then you have to prove to us you can do it’.

I didn’t really know what the hell I was doing so it took a lot of experimentation. But I was dead-set determined to do it.

I bought myself an Oberheim DSX sequencer and I had my brother’s TX816. MIDI was hard work in those days. I was syncing the DSX with my 16-track reel-to-reel via a striped SMPTE timecode track. Those do-it-yourself sessions got me my first record deal.

From there I graduated to a Linn 9000. Such an incredible device, taking floppy discs and inserting sounds onto the pads. You could sample! Wow, greatest thing ever.

That was a cool period. It carried me all the way to the early ’90s until one day my Linn 9000 blew up — in a cloud of smoke… gone.

After that I was at a crossroads. Should I invest in more dedicated hardware like an Akai MPC60 or invest in the future… software running on a computer?

I bought a Mac Se30 running Opcode Studio Vision and it was just the greatest frikkin’ program.

I became the go-to guy for not only my own records but for anything my brother Ricky was producing for Warner Brothers — because I could program and sequence.

Programming was a serious gig back then and I made a good living doing it.

We made David Sanborn’s entire album in 1996 on Studio Vision when it had two-track audio. It was also the early days of Pro Tools, or Sound Tools as it was then.

Unfortunately Opcode went bust. I moved to Pro Tools kicking and screaming, because it wasn’t an easy program to get your head around in those days. Now I couldn’t do without Pro Tools, it’s just the biggest creative workstation you can think of… almost to a fault.

By which I mean, you have to keep a close eye/ear on whether the technology is serving the song. If the technology is aiding you, then great, but if it’s not helping you deliver that emotion to the listener then back away. It must serve the song.

RESPONSES