Stereo Masterclass

Multi-Grammy winning classical engineer Tony Faulkner dishes on the development of a secret RØDE microphone prototype, stereo techniques for different occasions and recording Beethoven’s 9th at the Sydney Opera House.

AudioTechnology: What brings you to Australia, Tony?

Tony Faulkner: I’m here to finalise work I’ve been doing with Røde on some new microphone models. I worked for quite a long time with Peter Freedman [Røde founder] on the NTR ribbon, and I’ve always had a fascination with valve omnis like Neumann’s M50. Røde saw it as a challenge to come up with a microphone that had similar characteristics — the characteristics that most of us like about those old microphones — but without the grief associated with using them.

AT: Such as?

TF: Well… There’s the price of replacement tubes if they go wrong. Also, the power supplies are a pain in the neck and so are the connectors — those old Tuchel connectors and things like them don’t last; you only have to stand on them once or tug on them once and they fail. Modern microphones are much more sensible for a practical engineer. Leave the vintage microphones for the collectors.

AT: As part of the process of finalising the work on these new microphones, you’re using them to record a concert at the Sydney Opera House. What are you recording?

TF: It’s Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, which, for a lot of people, is the greatest symphony ever written. It has inspired so many people, and the message in the words and in the poetry is just… Well, it’s a great work.

AT: Who are the performers?

TF: It’s an orchestra called Anima Eterna Brugge, from Flanders, Belgium. They perform on period instruments and try to recreate an authentic experience, as it would have been performed when the pieces were composed. The conductor is Jos van Immerseel, and there are soloists from Norway, Sweden, Australia, America and Flanders. The Australian Brandenburg Choir is performing choral duties. It’s a musical United Nations!

Apparently if you translate the conductor’s name from the old Flemish, ‘immer’ means ‘forever’ and ‘seel’ means spirit or soul. If you then translate that into Latin you end up with ‘Anima Eterna’ — ‘Eternal Spirit’ — which is a nice little play on words, but also very appropriate because there is an eternal spirit in the Beethoven piece we’re recording tonight.

AT: What microphones are you using to record it?

TF: The main mics for this recording are the prototype tube mics — the temporary working title is the TFM50 but that’s just an internal bit of a laugh!

AT: Are they like the classic M50s with the diaphragm mounted on a sphere?

TF: Yep, so the effect of the sphere is that they’re omnidirectional at the lowest frequencies — probably 15 to 20 Hertz — but as you go up in frequency they become more directional; they’re cardioid-ish somewhere around 1kHz, and then they go hypercardioid above that. That means they have ‘reach’.

AT: So an instrument that is further away but on axis, such as a clarinet in an orchestra, will be captured with roughly the same tonal balance as an instrument that is closer but off-axis, such as the first violin?

TF: Yes. My understanding is that the original M50 was designed to be a single omnidirectional microphone to stick over a conductor’s head that would cover the whole orchestra in a typical German broadcast studio. That’s quite a nice way to work. It means you don’t have to put lots of mics out and mix them. Of course, back in the days when the original M50 came out they didn’t have consoles like we have now, so the idea of just sticking up one stand with one microphone on it was a very elegant and easy way to work.

AT: You’re using two…

TF: That’s because we’re in stereo!

AT: Of course! You’ve placed them about a metre behind the conductor. How far apart are they?

TF: I have a starting point of 67cm; that gives fairly decent in-phase coherent information from the centre of the image and gives a wide enough ambience that it sounds believable on its own. As it turns out, the main pair are forward of where the soloists are, so they also capture a believable stereo image of the soloists that doesn’t become unstable. I quite like that idea.

AT: You’ve got spot mics on the soloists as well.

TF: Yes. The soloists’ words wouldn’t be quite clear enough in the main pair for people who are used to listening to CDs of Beethoven’s 9th, so we’ve got some spot mics to cope.

AT: We’ll come back to the spot mics shortly. You’ve started with a pair of TFM50s, 67cm apart, somewhere behind the conductor. How high up are they?

TF: I would guess they’re about 3m.

AT: Do you place them relative to where the conductor’s head is?

TF: Yes, I’m terribly empirical. It’s my background: my earliest recordings were all of Renaissance polyphony, so my ideal recording approach is to just have a pair of microphones on a stand behind the conductor and put it up until it sounds nice.

AT: Effectively treating the conductor as the balance engineer?

TF: Yes. That’s the conductor’s job; the conductor is really the balance engineer. Quite a lot of conductors, particularly the older style ones, don’t like the idea of someone sitting in a control room pushing faders up and down because they feel that’s their job. If they decide they want the violas to sound a certain volume to make a particular texture, they don’t want someone else sitting in a control room pushing up a fader and thinking, ‘Oh gosh, the violas aren’t loud enough, turn them up!’ If you use something simple, like a main pair, then you tend to keep the conductors off your back.

I like to have a main pair doing the bulk of the work. The main pair might not be the complete finished article — I use spot mics to fill in what’s missing — but musically it’s got to be balanced and it’s got to have some perspective. Also, it’s got to have some bottom end, which the TFM50s have really got. It’s like a train going past!

AT: They sounded pretty big to me!

TF: Yes, indeed. They’ve got the sphere behind the diaphragm, they’ve got the tube circuit, they’ve got a custom-made Røde transformer, they produce a big sound and they’re reliable because they’re a modern design. I used them for some recordings late last year with the London Philharmonic and with the European Union Chamber Orchestra and I was very happy with the results, so when Peter invited me here to record this concert with them I couldn’t possibly turn it down.

AT: You mentioned filling in the missing parts with spot mics, and I noticed quite a few on the stage. What are you using?

TF: It’s quite an eccentric set up. They’re all ribbons, all NTRs. They are wonderful. I’m a great ribbon fan; I have a collection of Coles, RCAs, Beyers, Royers and Rødes, and I love them all. But the Røde NTR is a lot cleaner and brighter than most, and appears to have more bandwidth without sounding EQ’d… and it has ‘reach’. It’s quite dry as a spot microphone, which is what you want, but it doesn’t sound ugly like a lot of small diaphragm cardioids that sort of screech at you.

AT: Where are you using them?

TF: I’ve got one for each of the four soloists, and there’s a pair for the choir and a pair for the woodwind.

AT: I also noticed a couple over the string sections.

TF: They’re safety mics. There’s a couple of them lurking around in case we need them, because this is a live concert. If this was a recording session I could say, ‘Oh guys, can we take a short break while I put out a couple of more mics?’ but when you’re in a public concert there’s no doing that, so you put out a few other things in case you need them.

AT: Because you’ve only got one chance to capture it.

TF: Yes. And the music is the most important thing. It’s all very well saying, ‘let’s do it with just two mics’, as we talked about earlier, but if it isn’t working then it’s not doing the music or the performers any favours. With a concert you’re limited to where you can put microphones; you don’t have complete free rein because there’s an audience there. Say I wanted to put microphones in the front row of the audience… a few people might be upset!

AT: Unless you could hang them from the ceiling.

TF: Yes. Actually, we’ve got two ‘thinking man’s reverb’ mics hanging from the ceiling for this recording. They are also prototypes from Røde — omnis. They look remarkably like NT5s with omni capsules, but these are revised capsules and electronics and they’ve got a flat black finish, which is nice for television.

A guy who wrote a book on microphone techniques referred to the two bidirectionals as the ‘Faulkner Technique’. The first I knew of it was when the book came out

AT: They are end-address microphones and yet you have them pointed upwards, vertically. That shouldn’t make any difference with an omni, in theory, but in practice most omnis become a bit duller off axis.

TF: Yeah. Bizarre, isn’t it? Most people think I’m an idiot when I do that sort of thing but it’s particularly useful if you’re in a dead hall. Quite a lot of modern concert halls have got a short reverb time, maybe 0.7s or 0.8s, and that makes it quite hard to make a big string sound. When the producer or somebody says they want to hear more strings, they don’t really want to hear individual players shrieking on the E string, they just want a ‘bigger’ sound. That often means more reverb. For example, I did a cycle of Vaughan Williams symphonies with the BBC Orchestra and Sir Andrew Davis; they wanted a lusher string sound in the slow movements so I twisted the M50 outriggers back to front.

AT: So they were pointing at the back of the hall instead of at the strings?

TF: Yes. You still get the same ‘weight’ coming from the strings but it’s more blended and smoother, and it’s more effective than turning on some kind of reverb box. There’s less detail from individual players, but if it’s a slow movement of a Vaughan Williams symphony that’s the sort of sound you want. It wouldn’t work for a finale because when the brass gets going it’s going to sound like an echo return!

AT: What did you think of the prototype microphones in that ‘thinking man’s reverb’ configuration?

TF: I’m very impressed with them, and I can use more of them than I had expected to. Sometimes, if you use some particular single diaphragm omni pencil mics for this purpose, you can’t add enough because it starts sounding phasey, but these prototypes from Røde seem very coherent with each other as a pair. They will give us a lot of control over the reverberation time, which is what we want when we’re recording a concert and we don’t know how big the audience will be or how much they will affect the venue’s reverb time.

AT: On the topic of sounding ‘phasey’, how far apart are they?

TF: For me, outriggers would be typically 1.8m either side of the conductor and in line with the main rig. In an ideal world, one would like to be able to adjust the spacing until it sounded appropriately de-correlated, but in the real world they end up rather loosely set up as defined by holes in the ceiling or anchor-points on the lighting rig for dropping cables. In the case of this recording we used the existing cable cradles that the concert hall had hanging from above, so it was a bit empirical. Jason Blackwell [Sydney Opera House recording engineer] sorted it out very helpfully because he knew what was possible using the existing cabling.

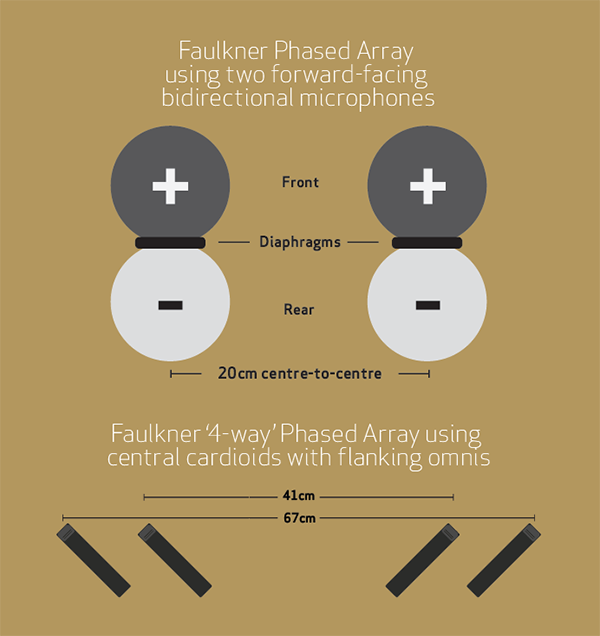

AT: You’re known for a couple of specific microphone techniques that you’re not using on this recording. One of those is two forward-facing bidirectional microphones spaced 20cm apart. It’s often referred to as the ‘Faulkner Technique’. What do you call it?

TF: I call it a ‘phased array’. One of my best friends when I was a student was a guy called Granville Cooper who worked on background radar for a living, and loved recording on the side. I told him about this funny technique I’d used with a couple of figure-of-eights about a foot or so apart, and that it worked for stereo. After taking a listen he said, ‘This is amazing. You know what this is, don’t you? It’s a phased array.’

AT: Right, he was drawing an analogy with using an array of side-by-side antennas to increase directionality and focus in broadcast and radar applications, also called a ‘phased array’. So as a microphone array it should work well at longer distances?

TF: Yes. The main thing that interested me about it — apart from the fact that it gives you useful stereo — is that if you’re in a place with a rather oppressive or overwhelming acoustic that you’d prefer to have less of, the null of the figure-of-eight pattern gets rid of reflections from the ceiling, floor and sides.

AT: When did you come up with that approach?

TF: The first time I used it in anger was in early 1981 at St Jude-on-the-Hill in Hampstead, London. It’s a huge acoustic — a beautiful acoustic — but with a very long reverb time, and I was trying to record Monteverdi trios with a small consort of strings. It was beautiful music, but whatever I did it sounded like I was in the Taj Mahal. That’s lovely if that’s what you want, but it wasn’t of commercial viability. In desperation I tried crossed figure-of-eights but it was still too wet, and I tried moving in closer but then it was too wide. So I thought, ‘let’s have a go at this, I’ve got nothing to lose’, and it sounded lovely. It works very well with the Røde NTRs, by the way.

AT: So you were just trying to solve a problem?

TF: Yep. It’s a problem solver for someone like me who is always on the road. I don’t usually have the luxury of working in a studio or hall with controlled acoustics. I could be in a church or in a works canteen, all sorts of places, and it’s nice to have techniques that can help you get rid of too much acoustic.

About five years ago somebody wanted me to go and record four hands piano, Schubert’s Three Marches Militaires, in a small chapel near Bordeaux. Lovely job to have, and lovely wine around there, but the chapel’s reverb was about 4.8s long without an audience in the room. With four hands on a piano playing Three Marches Militaires it just sounded ridiculous; like I’d got a reverb for Christmas and was putting it on everything! I ended up using a pair of ribbons, and found a local recording studio that lent me some of those semi-circular things to place behind microphones for getting rid of the room sound if you’re recording in a bedroom or similar. It looked bizarre but it worked, and it sounded lovely.

AT: I’m assuming the chapel sounded fine with an audience in it?

TF: It did indeed. We had an audience on the last day for the concert and they added a lot of absorption. With 120 people in there the reverb time came down to something much more manageable.

AT: You played me a lovely recording you did with that method just recently.

TF: Yes, Voice Trio, an English group of three young ladies. That was recorded in a small stone leper’s chapel, about 4m x 5m x 5m and with quite a ‘slappy’ reverberant quality.

AT: A rough stone finish?

TF: No, quite shiny and harsh; but it sounded beautiful to them when they were singing, which was the main reason we were there. As a problem solver I recorded it with a pair of NTRs in a phased array. I’m very pleased with it, and so are they. But there are quite a few orthodox people who would certify me for using such a funny microphone technique!

AT: If they knew what you did!

TF: Yeah! If they don’t know it doesn’t matter, does it?

AT: There’s another technique that has been attributed to you, using two omnis and two cardioids on the same stereo bar.

TF: The four-way phased array… all mounted on a wide stereo bar, 66.7cm apart for the omnis on the outside with a pair of cardioids in between.

AT: How do you configure the cardioids?

TF: I started out with ORTF and subsequently NOS, but those spacings didn’t work in the array because I wanted it to deliver ‘reach’. Keeping the angle between the mics at 90°, as for NOS, I tried dividing my 66.7cm omni spacing by the Golden Ratio number of 1.618 and arrived at 41.2cm, and there it has stuck!

AT: I doubt anyone is going to fuss over those fractions of millimeters!

TF: They’re starting points. Setting the spacings and angles in stone with a microscope is not the best idea because much in sound and stereo is about time as well as distance, and the speed of sound varies with altitude, temperature, etc., which affects the time and phase relationship between microphones. Halls sound different depending on the time of day, the temperature, the humidity, and so on. Watford Town Hall, for example, used to be known for sounding different in the afternoon than in the morning, and engineers would move their mics up in the afternoon to find more sense of space.

AT: When do you use the four-way array?

TF: I do a lot of work for video companies where I’ve got to record an orchestra but I’ve only got half an hour to set up, so I’ll stick one stand up with a crossbar on it and four mics — Røde NT6s or whatever — and that will give me the whole orchestra. That’s really quite handy because most of my colleagues would stick out at least 15 microphones, sometimes up to 50 on a symphony orchestra in a place like the Barbican. Everybody is pleased to see me if I just stick one stand up and run one multiway cable and do it all in less than 10 minutes.

AT: And where do you place that?

TF: About a metre or so behind and above the conductor. The omnis are usually a bit too fat and ‘puddingy’ and the cardioids are usually a bit too thin and scratchy, so you’ve got a choice. Blend it all together when you get home.

There are other people who use four-way arrays, and I must give them credit. There’s a guy called Huw Thomas at BBC Wales. I had a job at St Davids Hall in Cardiff and the BBC was covering the same concert. I put up my mics and one of their guys said, “Huw, you’ve got to come out here; this guy’s a nutter like you!” He had a similar concept except he was using four omnis. A bit different but he did it for the same reason — he wanted the sound that he liked from his omnis, but he wanted it to reach in a bit further rather than just being the front desks and everybody else sounding a bit up and out. Even though they’re omnis, you still get the forward gain because they’re in an array. The late Onno Scholze from Philips also had a concept of four omnis in a row, slightly wider spacing, but still using arrival time differences — phase differences — to help your hearing sort out what is going on.

Engineers who use four-way arrays for recording live concerts are quite enthusiastic about it. They’re the same as me; often they walk into a place and they’ve got very little time to set up. Let’s say it’s the Messiah; the concert’s sold out, there’s nowhere on stage to put microphones and you haven’t got time to hang anything. Well, you’ve got to do something! The four-way array is a good solution. It doesn’t function at its best with close recordings, but it is not intended to do so.

AT: I’ve seen arguments on forums over what the ‘Faulkner Technique’ is. Some argue that it is the two bidirectionals, others argue that it is the four mics on the bar. You call both of them ‘phased arrays’.

TF: Yes, I do. By the way, I never called either of them the ‘Faulkner Technique’. A guy who wrote a book on microphone techniques referred to the two bidirectionals as the ‘Faulkner Technique’. The first I knew of it was when the book came out.

AT: You may as well embrace it!

TF: Of course!

AT: We started this interview talking about your development work with Røde and using its prototype microphones to record tonight’s concert. I think it would be appropriate to end this interview by asking how your involvement with Røde began?

TF: My first connection with Røde was via the NT6 omnis. I was having problems with the mics I normally use and had sent them back to be fixed. Out of the blue a job came up to record a concert, and it required a four-way array with relatively small microphones. I asked around to find out if the NT6s were any good; I did not know much about Røde at that time except they were not overpriced and many of my musician friends loved them for their home studios. I ended up buying four NT6s plus two omni capsules, and — shock, horror — I liked them!

When I got my other mics back I did a double-blind shootout and found the NT6 with omni capsule to be at least a match for my other mics, and a very fine mic in its own right. It is more ‘omni’ than some of the more expensive mics and has more bass extension than some of them as well, which is good for me. I contacted Røde to tell them what I thought about the NT6, and the rest is history.

I’ve worked with Røde on numerous concepts and prototypes since then. I like the company’s attitude to quality, enthusiasm for innovation, and — most especially — lack of bullshit. When I first started using Røde mics some snobs turned their noses up or thought I had lost it, but thank goodness there is no problem like that any more. I never leave home without at least a pair of Røde mics in my kit — except when I came to Sydney this time, of course, because I knew in advance there would be some here for me to record this concert.

Anima Eterna Brugge & The Australian Brandenburg Choir: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 at the Sydney Opera House is on DVD and Blu-ray at Store.Rode.com

RESPONSES